Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis

Introduction

Within the spectrum of allergic eye diseases, atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC), along with perennial allergic conjunctivitis (PAC) (Ch. 13), vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) (Ch. 14) and, to a certain extent, giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) (Ch. 16), is categorized as a form of chronic allergic conjunctivitis (CAC). Along with the milder, more acute seasonal allergic conjunctivitis (SAC) (Ch. 13), these conditions characteristically involve an IgE-mediated type I hypersensitivity response, manifested by papillary conjunctivitis, with itching as a universal early symptom. However, the more chronic AKC, along with VKC, is distinguished from seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis, by the complex recruitment of other immunologic mechanisms, including a prominent T-cell-mediated type IV hypersensitivity response, as well as a variety of other inflammatory cell types and cytokines. The potential for corneal involvement and opacification increases significantly with the CACs because of the severity and sustained nature of their inflammation. The highest incidence of visual loss is therefore, found in the most chronic of these disorders, AKC.

Definition and Associated Risk Factors

Atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) was first described in 1952 by Hogan, who described five cases of atopic eczema associated with bilateral keratoconjunctivitis.1 He recognized an association between the skin and eye findings, coining the term ‘atopic keratoconjunctivitis.’ His patients were notable for chronic conjunctival hyperemia and thickening, corneal epitheliopathy, and later corneal scarring and neovascularization. Based on his observations, he outlined several criteria to aid in diagnosing this unique condition: the presence or history of eczematous dermatitis, a family history of atopic disease, associated allergies (asthma, hay fever), eosinophilia, and a characteristic keratoconjunctivitis associated with exacerbations of the dermatitis.

Few studies have established the incidence of AKC. However, atopic dermatitis (AD), its most frequent extraocular association, has been estimated to affect between 5% and 20% of the general population, making it the most common chronic inflammatory condition of the skin. The incidence of AD is greatest in the pediatric population Twenty-five to forty-two percent of AD patients are found to have ocular involvement.2,3 AKC may occur at any time after the onset of the associated dermatitis or other atopic condition, and is not necessarily correlated with exacerbations of these conditions.4 The initial presentation of ocular symptoms in AKC most commonly occurs in the second to third decade of life, with some patients presenting earlier or later. Visually significant complications most frequently occur in the fourth to fifth decades, with more men affected than women. The condition then remains chronic for years, usually requiring lifelong treatment. Studies suggest that an earlier onset of AKC, for example in childhood, carries the greatest risk for tear film abnormalities and greater ocular surface damage.5 A survey of CAC in a referral practice found that AKC and VKC were equally observed (39% each), while 13% were diagnosed with PAC.6 However, the chronicity and visual complications of AKC would be expected to skew this population, causing AKC to be over-represented in referral practice, when compared to the general population.

As suggested by Hogan, the strong association between AKC and eczematous dermatitis cannot be overemphasized, with at least 95% of AKC cases presenting in patients with some history of this chronic skin condition.7 Other atopic conditions associated with AKC include asthma and allergic rhinitis, each seen in 65–87% of AKC patients.8 Although a handful of case reports have described AKC without other atopic disease, later investigation will usually reveal some form of systemic atopy. Patients will also frequently describe a family history of atopy. Recently, Guglielmetti et al. have suggested that Hogan’s definition be modified to include the clinical features described below, combined with the presence of any atopic condition (e.g. atopic dermatitis, periocular eczema, asthma), occurring at any time point during the atopy, independent of its severity, and exhibiting corneal involvement at some point in the course of disease.4

Clinical Presentation

Eyelids

The periorbital skin and eyelids display a scaling, flaky dermatitis consistent with eczema (Fig. 15.1). There may be periorbital hyperpigmentation, which may lighten in response to control of the inflammation. In long-standing AKC, de Hertoghe sign, or absence of the lateral brow, is occasionally seen and may also be related to chronic eye rubbing. Vertical corrugations near the medial canthus of the upper and lower eyelid may also result. The eyelid margins may be thickened, edematous, and hyperemic. Eyelid edema may lead to Dennie–Morgan lines, single or double creases in the lower eyelid. The eyelid skin is often fissured, and lateral canthal ulceration related to chronic tearing may be present (Fig. 15.2). Lid malposition (usually ectropion), ptosis, lagophthalmos and madarosis may all result from chronic eyelid edema and inflammation. The chronic edema can lead to permanent lid swelling, a hallmark of long-standing atopic eye disease. Keratinization of the eyelid margins is sometimes observed, along with associated meibomianitis and obliteration of meibomian glands.

Conjunctiva

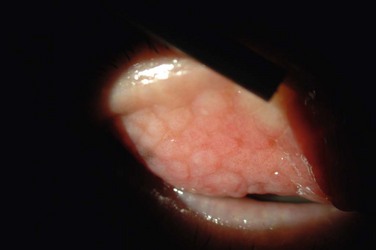

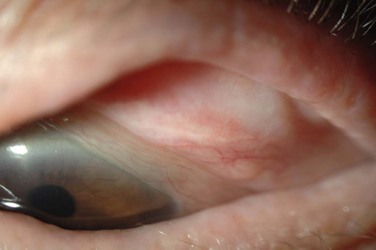

The palpebral conjunctiva reveals papillary hypertrophy, more prominent on the lower tarsus. There may be giant papillae as in VKC (Fig. 15.3). Diffuse sheet-like infiltration of the conjunctiva may lead to pale white edema and obscuration of blood vessels (Fig. 15.4). Conjunctival scarring may occur, often in a reticular or septal pattern (Fig. 15.5). Subepithelial fibrosis can, in severe cases, lead to symblephara, inferior forniceal foreshortening, and cicatricial ectropion. The bulbar conjunctiva typically displays diffuse chemosis and injection. The limbus may become infiltrated and edematous, and gelatinous limbal hyperplasia, consisting of confluent macropapillae, is sometimes seen. Trantas dots, tiny white lesions consisting of necrotic epithelial cells and eosinophils, may be observed, similar to those in VKC (Fig. 15.6).

Figure 15.6 Trantas dots and pannus of the superior cornea.

Cornea

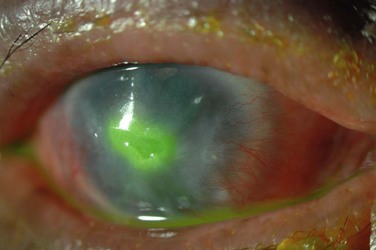

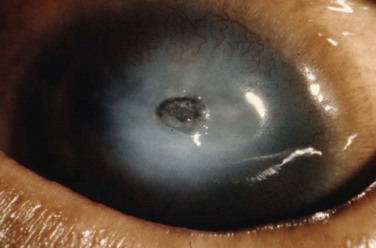

Corneal disease may be complicated by the late development of corneal hypesthesia in patients with AKC, resulting in a paradoxic reduction in surface symptoms, including itching. Punctate epithelial keratopathy is the most common corneal finding. Filamentary keratitis may occur, sometimes with very thick mucoid filamentary strands and possibly related to tear film instability, due to goblet cell abnormalities and deficient mucin secretion, also commonly featured in AKC. Persistent epithelial defects frequently occur in the setting of a dry and inflamed ocular surface and may eventually lead to macroerosions (Fig. 15.7). These pose a particular problem in the atopic patient and can progress to frank bacterial ulcers. Atopic shield ulcers with ‘vernal’ plaque formation may also develop. Histologically, these adherent mucus plaques contain epithelial debris, eosinophils, and inflammatory cells, and probably result from a combination of mechanical irritation from giant papillae, as well as toxic epithelial changes secondary to inflammation. Persistence of these plaques may eventually cause stromal thinning and perforation (Fig. 15.8). The chronic inflammation and mechanical insult from palpebral scarring may eventually result in partial or total limbal stem cell deficiency (Fig. 15.9). Chronic inflammation and superimposed infection may lead to corneal scarring, neovascularization, and lipid deposition. Severe pannus often develops, typically affecting the superior one-third of the cornea. Vision may decline due to obscuration of the visual axis, irregular astigmatism, and/or ocular surface compromise. A pseudogerontoxon may be seen in the peripheral cornea, which resembles a short, circumferential segment of arcus senilis. This localized area of lipid deposition, related to abnormal vascular permeability at the limbus, may be the only evidence of previous atopic disease in a quiet eye.9

Other complications

Eyelid inflammation is common in AKC, often related to staphylococcal blepharitis. In fact, patients with atopic dermatitis are found to have high rates of bacterial skin colonization, specifically with staphylococcal species. AKC patients are at higher risk of corneal superinfections because of an unstable ocular surface, the local bacterial colonization of the eyelids, and a dysfunctional innate immune system.10 Herpes simplex keratitis, frequently bilateral, is another well-known complication of AKC, and is presumably related to abnormalities in the atopic host’s immune defenses (Fig. 15.10). Herpetic epithelial lesions may be recurrent, especially when topical or systemic immunosuppressants are required to control the atopic state.11 Management is especially difficult because epithelial AKC lesions may be difficult to distinguish from HSV keratitis.

Rapidly progressive cataracts frequently develop in AKC patients, classically described as anterior subcapsular opacities, usually stellate or shield-like in appearance. The pathogenesis for atopic cataract is unclear, though some have suggested that high levels of IgE may be correlated with development of cataract in these patients.12 The chronic use of topical steroids also predisposes to posterior subcapsular cataracts in AKC patients. Other forms of cataract may form independent of corticosteroid use, especially in patients with severe systemic atopic disease.

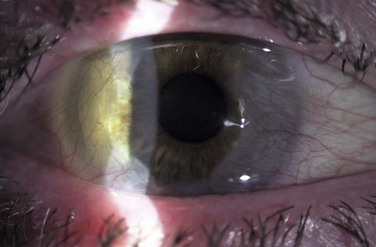

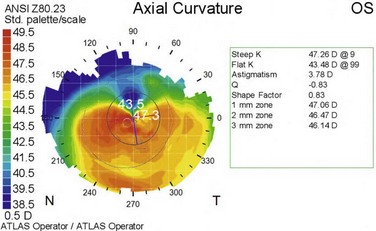

A higher incidence of keratoconus and pellucid marginal degeneration has been reported in AKC patients, likely related in part to chronic eye rubbing (Fig. 15.11).3,13 Interestingly, a slightly higher rate of retinal detachment has also been noted in AKC patients. This may also be related to chronic eye rubbing, inducing degenerative vitreous changes.14

Figure 15.11 Contralateral eye from patient depicted in Figure 15.10, showing keratoconus on corneal topography.

Power and colleagues reported on the frequency of different clinical features in AKC, based on long-term follow-up (average, 7 years) of a cohort of 20 AKC patients.8 In their series, all 20 patients had eczema, and half had a family member affected with atopy. All patients had conjunctival hyperemia, and 65% had papillary reaction. Roughly half displayed some form of conjunctival scarring, including subepithelial fibrosis, forniceal foreshortening and symblepharon formation. All patients had superficial punctate keratitis. Fourteen of the 20 patients had severe corneal complications, including persistent epithelial defect (seen in half of the patients), corneal ulceration, or bacterial keratitis. Three patients developed herpetic keratitis. Two had keratoconus. Seven patients (nine eyes) required penetrating keratoplasty, some for corneal perforation.

Immunology and Pathogenesis

All ocular allergic disorders are characterized by a hypersensitivity response, defined as an excessive reaction of the normal immune system, usually by exposure to an inciting antigen. Type I hypersensitivity, or IgE-mediated immediate hypersensitivity, predominates in PAC and SAC, but is also involved in other CACs, including AKC. By its nature, common inciting antigens are more easily identified in SAC because of the acute inflammatory response, and is evidenced by the exposure and seasonal pattern seen in SAC. Serum IgE levels are chronically elevated in AKC patients, as seen in individuals with other forms of atopy, but their levels are not necessarily correlated to severity of disease. Notably, serum IgE levels in AKC patients are higher than in patients with allergic conjunctivitis, probably reflecting a more chronic atopic state.15 IgE levels in tear samples are also increased in AKC, and correlate with serum IgE levels.15 However, AKC additionally involves a chronic inflammation of the ocular surface, a type IV delayed hypersensitivity response, where an immediate antigen is not easily identified.

A genetic predisposition combined with antigen sensitization is suspected in AKC and in its associated disease, atopic dermatitis. AKC may, however, represent either a common manifestation end point for a number of abnormal gene processes, or a single gene defect with variable phenotypic expression, modified by other gene polymorphisms and the environment. Tabbara et al. described the acquisition of new VKC and AKC after bone marrow transplantation, suggesting that the origin of atopy might lie in an abnormality of the pluripotential marrow stem cells.16 Further more, a recently recognized Th2 cytokine, which may be involved in mast cell activation, IL-33, has been found to be up-regulated in giant papillae in AKC.17 IL-33 is a ligand for ST2L, the gene for which an association with atopic dermatitis has been suggested. More recent studies suggest that an epithelial barrier defect may be responsible rather than a defect in immunoregulatory function. A strong association of a defect in the Filaggrin gene (FLG) with atopic dermatitis, asthma, eczema and ichthyosis vulgaris, has been described and confirmed in multiple pedigrees of families with AD. The filaggrin protein is not only an abundant and essential component of epithelial barrier function; its breakdown products are responsible for epithelial homeostasis, forming the skin’s natural moisturizing factor (NMF).18 Despite its association with asthma, filaggrin is not found in the bronchioles, suggesting that FLG mutations lead to a defective barrier which may allow earlier and stronger systemic antigen sensitization. A similar mechanism may contribute to AKC, where external eyelid administration of immunosuppressant creams has been found to reduce ocular surface signs and symptoms. Reductions of NMF has also been shown to raise the pH of keratinized epithelium which promotes the growth and colonization of Staphylococcus aureus, commonly found in atopic dermatitis, which contribute to the activation of innate immunity.

Histologic Studies

However, most of the immunologic characterizations of AKC, to date, have involved the characterization of the pathways up-regulated in this inflammatory state, without specific regard to its genesis. In contrast to seasonal and perennial conjunctivitis, in which mast cells are primarily implicated, histologic examination and immunohistochemical studies of conjunctival specimens reveal increased numbers of mast cells, eosinophils, T lymphocytes, and neutrophils in AKC patients, relative to normal controls.19–23 Mast cells and eosinophils have not only been detected in conjunctival epithelium, a pathologic finding, but are also present in increased numbers in the substantia propria. A surplus of Langerhans cells, macrophages and B cells in the substantia propria is also seen.19 Indeed, while topical mast cell stabilizers are often effective in managing the signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis, they are rarely adequate in controlling AKC.

T Lymphocytes

The cytokines involved in the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells in AKC have been studied extensively, with particular attention to T-cell cytokines. In most studies, Th2 cytokines are prominent, with increased levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-13 detected in both conjunctival and tear samples from AKC patients.23–25 Tear levels of IL-5 have been suggested as a marker for severity of AKC, and IL-4 levels may be correlated with exacerbations in dermatologic atopy.25 Elevated levels of IL-4-producing T cells were also observed in peripheral blood samples of AKC patients.23 However, other studies suggest, a preferential up-regulation of Th1 cytokines, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), in AKC.20

Eosinophils

Activated eosinophils are instrumental in recruiting additional inflammatory cells to the ocular surface. They release chemoattractants, such as IL-8, which attracts neutrophils to the conjunctiva; IL-8 is found to be highly expressed by eosinophils in AKC.26 They secrete IL-4, attracting Th2 cells, as well as the chemoattractants RANTES and MCP-1.24 Eosinophils are also major players in the development of sight-threatening corneal complications in AKC. Upon degranulation, they secrete leukotrienes, promoting allergic inflammation, as well as toxic proteins, including major basic protein (MBP) and eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP). MBP and ECP are known to induce damage to the corneal epithelium, causing superficial punctate keratopathy as well as frank corneal ulceration.27 In vitro, these proteins have been observed to reduce corneal epithelial cell viability and cause morphologic changes.28 Pathologic studies of corneal buttons from AKC patients show evidence of eosinophils and eosinophil byproducts in shield ulcers; notably, this applied to the area of the ulcer as well as surrounding ‘healthy’ stroma.29

Conjunctival Epithelial Cells and Fibroblasts

In addition to traditional inflammatory cells, other cell types express pro-inflammatory mediators in AKC. Recently, the active role played by conjunctival epithelial cells and fibroblasts has been recognized. The expression of surface adhesion molecules and the release of cytokines by epithelial cells enhance recruitment of eosinophils; notably, the surface adhesion molecule ICAM-1, which binds eosinophils, is strongly expressed by conjunctival epithelial cells in AKC.30 Expression of Toll-like receptor 3 has also been detected on the surface of conjunctival epithelial cells, and may be involved in recruitment of eosinophils.31 Conjunctival fibroblasts, when activated by Th cytokines, such as IL-4, TNF-α, or IL-13, produce the chemokines eotaxin-1 and eotaxin-2. These promote local accumulation of eosinophils and enhance eosinophil degranulation.32 Interestingly, eotaxin can also be produced by activated corneal keratocytes (corneal fibroblasts), attracting eosinophils into the cornea and causing degranulation of epitheliotoxic proteins. Conjunctival fibroblasts were found to constitutively express IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and RANTES, all of which enhance inflammatory cell accumulation in the conjunctiva.24 Recently, it has been suggested that thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TLSP), which recruits Th2 cells and may be involved in allergic inflammation, can be expressed on conjunctival epithelial cells.33

Secondary Structural Changes

Extensive inflammation in AKC leads to chronic ocular surface alterations. Both goblet cell loss, based on impression cytology,34 as well as goblet cell hyperplasia, based on conjunctival biopsy,8 have been reported. Tear film instability, with increased tear break-up time but normal tear production, has also been described. Goblet cell production of mucins is altered, with decreased levels of the primary tear mucin MUC5AC, and increased levels of MUC 1, 2 and 4.35 Of note, MUC5AC production was most dramatically reduced in patients with significant epithelial disease or shield ulcers. These patients also had increased numbers of conjunctival eosinophils and neutrophils, compared to AKC patients without significant epithelial disease, consistent with the role these cells play in corneal epithelial damage.34 It is likely that goblet cell proliferation and mucin production are affected by inflammatory cytokines present in the conjunctiva in AKC patients. Corneal sensitivity is also reduced in AKC, and this may be related to abnormal corneal nerve architecture, noted in AKC patients on confocal microscopy. AKC patients had thicker corneal nerves with deflection and bifurcation anomalies, as well as increased tortuosity.36 Squamous metaplasia has also been described in AKC.34

Differentiation from Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis

While the immunopathogenesis of AKC and VKC is very similar, a few differences have been reported. Tear levels of IL-4 have been found to be significantly higher in AKC patients, compared to those with VKC; it has been suggested that this may reflect a higher systemic level of Th-mediated inflammation in AKC patients, related to atopic dermatitis, rather than local ocular inflammation.25 A study of cytokine expression in conjunctival-derived T-cell lines from AKC and VKC patients found greater expression of Th1 cytokines in AKC, compared to VKC, in which Th2 cytokines were more predominantly expressed.20 However, another study found that the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ was more highly expressed in VKC tear levels, compared to AKC.24 Additional studies are needed to better characterize differences in the immune pathology between AKC and VKC.

Management

More recently, effective control of AKC has been described with steroid-sparing immunosuppressive drugs, such as cyclosporine, a calcineurin inhibitor that reduces production of the cytokine IL-2, thereby reducing Th production. Immunohistochemical analysis of superior tarsal conjunctival biopsies in AKC patients treated with 2% topical cyclosporine A, revealed a reduction in the number of Th cells, B cells and macrophages after treatment, confirming the immunomodulatory effect of topical cyclosporine.37 A randomized, placebo-controlled trial found that topical cyclosporine A 2% in maize oil, was effective in treating signs and symptoms of AKC.38 However, side effects included intense stinging and prolonged blurred vision, which led some patients in the study to use the drops less frequently. A more recent randomized, controlled trial found that topical cyclosporine A 0.05% (Restasis) was also beneficial in treating AKC, and was tolerated much better, with fewer side effects.39 Tacrolimus, mentioned earlier, is also a calcineurin inhibitor, and inhibits T-cell production with greater potency than cyclosporine. An eye drop form is currently only available for use in Japan, but some reports describe improvement in AKC with tacrolimus ointment available as compounded formulation, either applied directly to the eye40 or to the eyelids, with presumed spillover onto the ocular surface.

Corneal epitheliopathy, erosions, and ulcerations in AKC should initially be managed as they would be in non-atopic individuals, albeit with appropriate titration of immunosuppressive therapy. Superficial punctate keratopathy requires aggressive lubrication, with preservative-free artificial tears and lubricating ointments, with the goal of increasing comfort and avoiding frank epithelial defects, which are typically more difficult to manage in atopes. If epithelial erosion does occur, topical antibiotic prophylaxis should be added to prevent bacterial superinfection and infectious keratitis, a complication of epithelial defects in AKC. All new epithelial defects should be cultured prior to initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Therapeutic measures, such as bandage contact lens placement and tarsorrhaphy should be utilized when needed, in order to facilitate healing of the defect. Shield ulcer plaques, consisting of epithelial and inflammatory debris at the base of an ulcer, are often resistant to treatment with topical anti-inflammatory therapy. Some have recommended surgical debridement of the plaque in such cases; in one report describing three patients, this led to complete re-epithelialization in all patients within a few weeks.41 Occasionally, it may be hard to distinguish a shield ulcer plaque from herpetic keratitis, and the latter should be kept in mind when faced with a plaque-like ulcerative lesion in an AKC patient.

Despite aggressive management, corneal scarring and occasionally perforation may occur in severe cases, necessitating penetrating keratoplasty. Results of penetrating keratoplasty are often poor in AKC patients, due to atopic inflammation and a compromised ocular surface. In a report of nine AKC patients who underwent penetrating keratoplasty, four of the nine patients required more than one graft. All patients were preoperatively treated with oral antihistamines, topical mast cell stabilizers, and topical corticosteroid for at least 5 days. Postoperatively, two patients were treated with topical cyclosporine A 2% and another with systemic cyclosporine in order to enhance graft survival. The authors note that final visual acuity results were quite favorable, but obtaining such results required aggressive control of inflammation and surface disease.42 Many advocate starting systemic immunosuppression with agents, such as prednisone or cyclosporine, beginning a few weeks prior to planned corneal transplant surgery, in order to limit risk of graft rejection. In patients with corneal epithelial or stromal irregularity but with good control of their AKC, scleral contact lenses may afford good vision and increased comfort without the need for surgery. Patients who develop limbal stem cell deficiency may require ocular surface stem cell transplantation for visual rehabilitation.

Other surgical measures may be considered in the management of AKC. Papillary resection with or without mitomycin-C application has been described as a method to reduce ocular surface inflammation. Clinical improvement was noted after resection, and decreased conjunctival inflammation was observed on cytologic analysis.43 In advanced AKC, extensive scarring of the ocular surface and eyelid margins may necessitate eyelid surgery. This includes lid margin tightening and rotational procedures for lid malposition, as well as symblephara lysis and forniceal reconstruction for severe conjunctival scarring. Many patients will require cataract surgery at a relatively young age due to atopic and steroid-induced cataract development. A few patients may need glaucoma filtering surgery or valve placement if steroid-induced glaucoma develops.

References

1. Hogan, MJ. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1952;50:265–281.

2. Garrity, JA, Liesegang, TJ. Ocular complications of atopic dermatitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1984;19:21–24.

3. Tuft, SJ, Kemeny, DM, Dart, JK, et al. Clinical features of atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:150–158.

4. Guglielmetti, S, Dart, JK, Calder, V. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:478–485.

5. Onguchi, T, Dogru, M, Okada, N, et al. The impact of the onset time of atopic keratoconjunctivitis on the tear function and ocular surface findings. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:569–571.

6. Marback, PM, de Freitas, D, Paranhos Junior, A, et al. [Epidemiological and clinical features of allergic conjunctivitis in a reference center]. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2007;70:312–316.

7. Bielory, B, Bielory, L. Atopic dermatitis and keratoconjunctivitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30:323–336.

8. Power, WJ, Tugal-Tutkun, I, Foster, CS. Long-term follow-up of patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:637–642.

9. Jeng, BH, Whitcher, JP, Margolis, TP. Pseudogerontoxon. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2004;32:433–434.

10. Nakata, K, Inoue, Y, Harada, J, et al. A high incidence of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in the external eyes of patients with atopic dermatitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:2167–2171.

11. Easty, D, Entwistle, C, Funk, A, et al. Herpes simplex keratitis and keratoconus in the atopic patient. A clinical and immunological study. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1975;95:267–276.

12. Uchio, E, Miyakawa, K, Ikezawa, Z, et al. Systemic and local immunological features of atopic dermatitis patients with ocular complications. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:82–87.

13. Jain, V, Nair, AG, Jain-Mhatre, K, et al. Pellucid marginal corneal disease in a case of atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:187–189.

14. Yoneda, K, Okamoto, H, Wada, Y, et al. Atopic retinal detachment. Report of four cases and a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:586–591.

15. Inada, N, Shoji, J, Kato, H, et al. Clinical evaluation of total IgE in tears of patients with allergic conjunctivitis disease using a novel application of the immunochromatography method. Allergol Int. 2009;58:585–589.

16. Tabbara, KF, Nassar, A, Ahmed, SO, et al. Acquisition of vernal and atopic keratoconjunctivitis after bone marrow transplantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:462–465.

17. Matsuda, A, Okayama, Y, Terai, N, et al. The role of interleukin-33 in chronic allergic conjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4646–4652.

18. O’Regan, GM, Irvine, AD. The role of filaggrin loss-of-function mutations in atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:406–410.

19. Foster, CS, Rice, BA, Dutt, JE. Immunopathology of atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1190–1196.

20. Calder, VL, Jolly, G, Hingorani, M, et al. Cytokine production and mRNA expression by conjunctival T-cell lines in chronic allergic eye disease. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:1214–1222.

21. Metz, DP, Bacon, AS, Holgate, S, et al. Phenotypic characterization of T cells infiltrating the conjunctiva in chronic allergic eye disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:686–696.

22. Trocme, SD, Leiferman, KM, George, T, et al. Neutrophil and eosinophil participation in atopic and vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Curr Eye Res. 2003;26:319–325.

23. Matsuura, N, Uchio, E, Nakazawa, M, et al. Predominance of infiltrating IL-4-producing T cells in conjunctiva of patients with allergic conjunctival disease. Curr Eye Res. 2004;29:235–243.

24. Leonardi, A, Curnow, SJ, Zhan, H, et al. Multiple cytokines in human tear specimens in seasonal and chronic allergic eye disease and in conjunctival fibroblast cultures. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:777–784.

25. Uchio, E, Ono, SY, Ikezawa, Z, et al. Tear levels of interferon-gamma, interleukin (IL) -2, IL-4 and IL-5 in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis and allergic conjunctivitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 1997;27:1328–1334.

26. Hingorani, M, Calder, V, Jolly, G, et al. Eosinophil surface antigen expression and cytokine production vary in different ocular allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:821–830.

27. Cameron, JA. Shield ulcers and plaques of the cornea in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:985–993.

28. Trocme, SD, Hallberg, CK, Gill, KS, et al. Effects of eosinophil granule proteins on human corneal epithelial cell viability and morphology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:593–599.

29. Messmer, EM, May, CA, Stefani, FH, et al. Toxic eosinophil granule protein deposition in corneal ulcerations and scars associated with atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:816–821.

30. Baudouin, C, Haouat, N, Brignole, F, et al. Immunopathological findings in conjunctival cells using immunofluorescence staining of impression cytology specimens. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:545–549.

31. Bonini, S, Micera, A, Iovieno, A, et al. Expression of Toll-like receptors in healthy and allergic conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1528. [[discussion 1548–29]].

32. Leonardi, A, Jose, PJ, Zhan, H, et al. Tear and mucus eotaxin-1 and eotaxin-2 in allergic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:487–492.

33. Ueta, M, Uematsu, S, Akira, S, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 enhances late-phase reaction of experimental allergic conjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1187–1189.

34. Dogru, M, Asano-Kato, N, Tanaka, M, et al. Ocular surface and MUC5AC alterations in atopic patients with corneal shield ulcers. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30:897–908.

35. Dogru, M, Okada, N, Asano-Kato, N, et al. Alterations of the ocular surface epithelial mucins 1, 2, 4 and the tear functions in patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:1556–1565.

36. Hu, Y, Matsumoto, Y, Adan, ES, et al. Corneal in vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy in patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:2004–2012.

37. Hingorani, M, Calder, VL, Buckley, RJ, et al. The immunomodulatory effect of topical cyclosporine A in atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:392–399.

38. Hingorani, M, Moodaley, L, Calder, VL, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topical cyclosporine A in steroid-dependent atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1715–1720.

39. Akpek, EK, Dart, JK, Watson, S, et al. A randomized trial of topical cyclosporine 0.05% in topical steroid-resistant atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:476–482.

40. Joseph, MA, Kaufman, HE, Insler, M. Topical tacrolimus ointment for treatment of refractory anterior segment inflammatory disorders. Cornea. 2005;24:417–420.

41. Solomon, A, Zamir, E, Levartovsky, S, et al. Surgical management of corneal plaques in vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a clinicopathologic study. Cornea. 2004;23:608–612.

42. Ghoraishi, M, Akova, YA, Tugal-Tutkun, I, et al. Penetrating keratoplasty in atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 1995;14:610–613.

43. Tanaka, M, Dogru, M, Takano, Y, et al. Quantitative evaluation of the early changes in ocular surface inflammation following MMC-aided papillary resection in severe allergic patients with corneal complications. Cornea. 2006;25:281–285.