19 Atopic Dermatitis

Clinical Presentation

Physical Examination

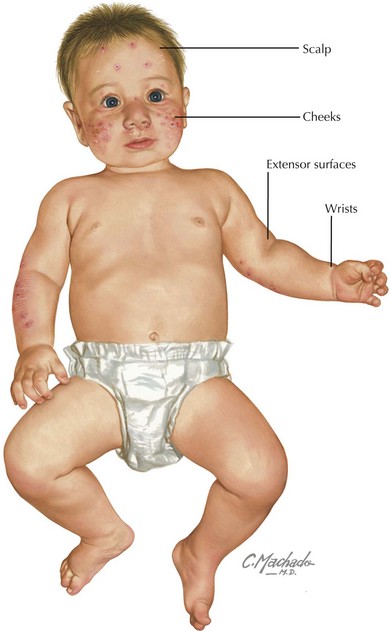

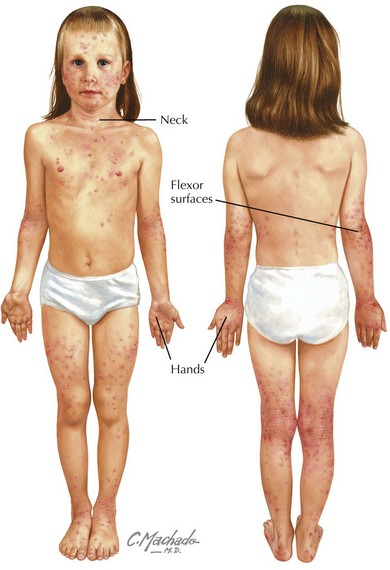

Physical examination of acute AD lesions reveals red papules and plaques that may also feature scaling, oozing, and crusting. In addition to acute lesions, children and adolescents with chronic AD may also have areas of thickened, dark skin (lichenification) at sites of prior acute lesions. The distribution of the rash is characteristic and varies by age. In infants, the cheeks, scalp, wrists, and extensor surfaces of the arms and legs are most affected (Figure 19-1). The diaper area is typically spared. The perioral and perinasal areas are rarely involved, leading to the characteristic “headlight sign” of pallor in these areas. In children and adolescents, the neck, hands, and flexor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities are more commonly affected (Figure 19-2).

Complications

Eczema Herpeticum

Secondary infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a potentially life-threatening complication that may affect children with AD of all ages. Vesicular lesions typically appear in groups superimposed on areas of skin affected by AD between 2 days and 2 weeks after exposure to HSV-1 or HSV-2. The lesions evolve to appear as “punched-out” hemorrhagic lesions with crusting (Figure 19-3). Associated symptoms may include fever, fatigue, and lymphadenopathy. Diagnosis may be made by Tzanck prep, direct fluorescent antibody, polymerase chain reaction, or viral culture from swabs of the affected area.

Evaluation and Management

Laboratory Testing

There are no laboratory studies essential in the diagnosis of AD. If checked for other reasons, a white blood cell count with differential may reveal an eosinophilia; a serum IgE may be elevated. In severe or refractory cases of AD, an evaluation by a pediatric allergist with skin testing (see Figure 18-3) or IgE assays for specific allergens (also known as radioallergosorbent testing [RAST]) may aid in identifying triggers that should be avoided. RAST results should be interpreted with caution because the assays often have high false-positive rates, and in the case of food allergens, subsequent elimination of foods, such as milk or eggs, poses nutritional risks.

Diagnosis

Hanifin and Rajka developed and validated a set of diagnostic criteria for AD in 1980 that remain the standard. Diagnosis is based on the presence of three major and three minor criteria (Box 19-1). The differential diagnosis of AD includes other primarily dermatologic diseases as well as systemic disease and immunodeficiency (Table 19-1).

| Diagnosis | Differentiating features |

|---|---|

| Contact dermatitis | History of contact with an allergen Distribution of eruption (exposed extremities for poison ivy, site of contact with button of pants for nickel) |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Nonpruritic Salmon colored, “greasy” appearance |

| Nummular eczema | Discrete round areas of erythema, scaling, and lichenification |

| Keratosis pilaris | Appearance of “goosebumps” Noninflammatory follicular papules |

| Psoriasis | Discrete plaques with well-defined irregular borders Thick scaling Nail involvement |

| Acrodermatitis enteropathica | U-shaped perioral rash with extremity and perineal involvement History of failed treatment for presumed fungal diaper dermatitis Associated with chronic diarrhea, growth delay, hair loss |

| Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome | T-cell immunodeficiency with severe AD, thrombocytopenia, and recurrent infections |

| Severe combined immunodeficiency | Combined (B and T cell) immunodeficiency with severe AD, diarrhea, failure to thrive, and life-threatening infections |

| Netherton syndrome | Disorder characterized by ichthyosis in the first 10 days of life, hair shaft abnormalities leading to easy breakage, and AD and other allergic disease Mental retardation may also be present |

AD, atopic dermatitis.

Approach to Therapy

The first-line therapy for reducing the inflammation associated with AD is topical corticosteroids. Ointments contain less alcohol than creams and are generally preferred because of better skin penetration, although older children and adolescents may prefer creams because of their less greasy feeling. These agents are available in a wide range of potencies. Maintenance therapy is typically initiated using a low-potency corticosteroid with a low likelihood of side effects, such as hydrocortisone 1% or 2.5%. Use of medium-potency agents such as fluocinolone 0.025% or triamcinolone 0.1%, or high-potency agents such as fluocinonide 0.05% may be used for short periods of time to treat severe flares but should not be used on the face or groin. Higher-potency agents are more commonly associated with side effects, including skin atrophy, striae, telangiectasias, hypopigmentation, and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression. Side effects are more likely to occur when these agents are applied to thin skin such as on the face, neck, or groin. For severe flares not controlled by topical therapy, a short course of systemic corticosteroids may be effective. Referral to an AD expert should be considered for children whose AD management is challenging (Box 19-2).

Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1483-1494.

Hanifen JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venerol (Stockh). 1980;92(suppl 92):44-47.

Krakowski AC, Eichenfield LF, Dohil MA. Management of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):812-824.

Palmer CNA, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2006;38(4):441-446.

Zutavern A, Brockow I, Schaaf B, et al. Timing of solid food introduction in relation to atopic dermatitis and atopic sensitization: results from a prospective birth cohort study. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):401-411.