Asymmetric Mandibular Excess Growth Patterns

• Hemimandibular Hyperplasia: Type I Condylar Hyperactivity

• Hemimandibular Elongation: Type II Condylar Hyperactivity

• Assessing Jaw Growth Maturity

• High Partial Condylectomy Procedure for Active Condylar Hyperactivity

• Presurgical Orthodontic Treatment

• Complications, Informed Consent, and Patient Education

• Malocclusion after Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

• Temporomandibular Disorders: The Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

A specific pattern of dentofacial deformity that occurs after birth and that primarily affects the mandible may be referred to as an asymmetric mandibular excess growth anomaly.* This is a useful term for name recognition, but it falls short of explaining the causes and effects of this common pattern of jaw deformity. This condition typically results in an uneven Angle Class III malocclusion, and it has been referred to by a variety of terms, including deviated mandibular prognathism, condylar hyperplasia, mandibular lateral gnathism, osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle, and asymmetric Class III dentofacial deformity. The overall effect on maxillofacial morphology also includes the secondary deformities that occur to the maxilla, the nose, the chin region, the position of the teeth, and the distortions that are visually observed in the overlying soft-tissue envelope. These effects are dependent on multiple factors, including the intensity of the mandibular hyperactivity; the patient’s age when the abnormal bone growth begins; any underlying hereditary dentofacial deformity tendency; and the treatment that was previously rendered (i.e., orthodontic, dental, or surgical) before the patient’s arrival to the surgeon for evaluation. These asymmetric mandibular excess growth patterns may be confused with other causes of maxillomandibular asymmetry (i.e., hemifacial hyperplasia, hemifacial microsomia, growth disturbance after a condyle injury during childhood).10,27,48,49,55,93,94,124 Most misdiagnosis are easily clarified by taking an accurate history, completing a physical examination, and reviewing the patient’s radiographs (Fig. 22-1).

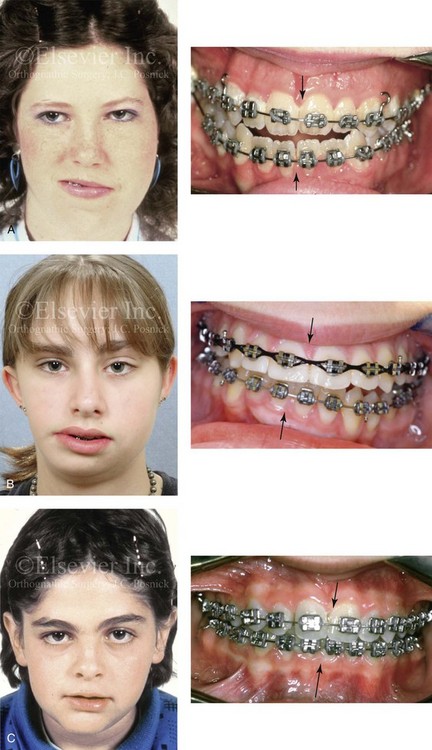

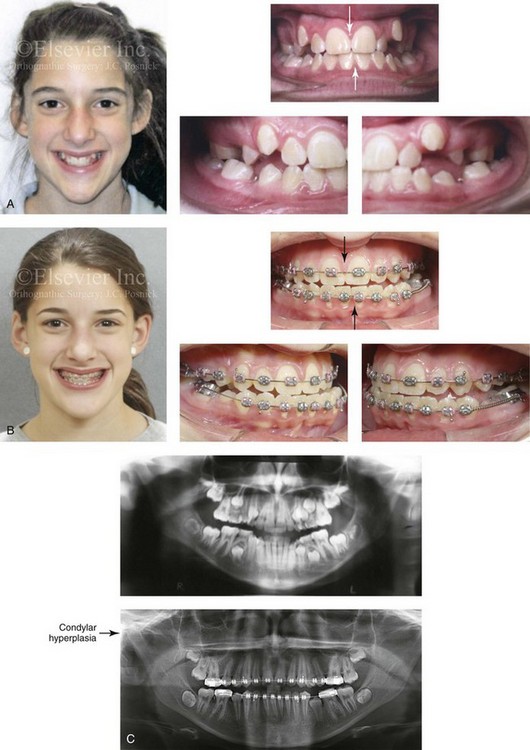

Figure 22-1 Asymmetric mandibular excess growth patterns are often confused with other causes of maxillomandibular asymmetry. Most misdiagnoses are easily clarified by taking an accurate patient history, completing a physical examination, and reviewing the patient’s radiographs. A, A teenage girl with hemifacial hyperplasia of the right side is shown. This anomaly involves the overgrowth of both the soft and hard tissues on one side of the face. There is an asymmetric Class III malocclusion with a shift of the mandibular dental midline to the opposite side. B, Hemifacial microsomia results in the deficiency of tissues within the first and second brachial arches on one side of the face. The intraoral examination is usually consistent with an asymmetric Class II excess overjet malocclusion. This 15-year-old girl with hemifacial microsomia of the right side demonstrates these findings. There is a shift of the mandibular dental midline toward the ipsilateral side. C, A 12-year-old boy in the permanent dentition sustained a right condyle fracture of the mandible earlier during his life with resulting ipsilateral (right side) mandibular hypoplasia and secondary deformities of the maxilla. He presented with an asymmetric Class II deep-bite malocclusion. There is a shift of the mandibular dental midline toward the ipsilateral side. The overlying soft-tissue envelope is distorted but not malformed.

Obwegeser believes that this dentofacial deformity is caused by two different growth regulators.23–25,68–91 The first is a more rare form, and it is clinically characterized by an increase in volume of all parts of the affected side of the mandible, without a lateral shift of the chin to the opposite side. Its primary effects end near the midline at the symphysis (Figs. 22-2 through 22-5). The second and more common form of this dentofacial deformity is characterized by an elongation of the affected side of the mandible, often with widening of the gonial angle and with clear displacement (i.e. lateral shift) of the midline of the chin and the mandibular dental midline to the opposite side of the face (Figs. 22-6 through 22-14).

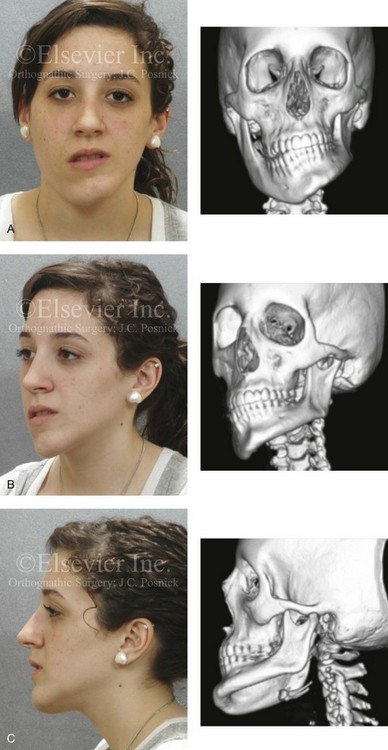

Figure 22-2 A teenage girl with right side hemimandibular hyperplasia. She demonstrates a typical phenotype as described within the chapter. A, Frontal facial and computed tomography (CT) scan views without intervention. B, Left facial oblique and CT scan views without intervention. C, Left profile and CT scan views without intervention. D, Right facial oblique and CT scan views without intervention. E, Right profile and CT scan views without intervention. F, Frontal and submental vertex CT scan views without intervention.

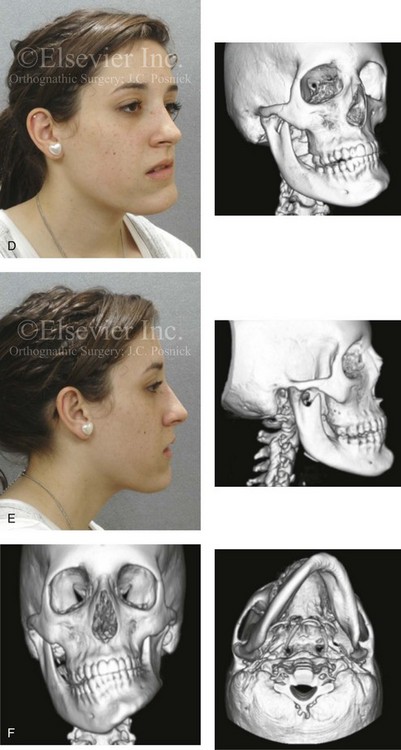

Figure 22-3 A woman in her early 20s with left side hemimandibular hyperplasia. She demonstrates a typical phenotype as described within the chapter. A, Frontal facial and occlusal views without intervention. B, Facial and posteroanterior cephalometric views without intervention. C, Right profile and lateral cephalometric views without intervention. D, Asymmetry of the mandibular inferior borders is demonstrated in the left and right facial oblique views without intervention.

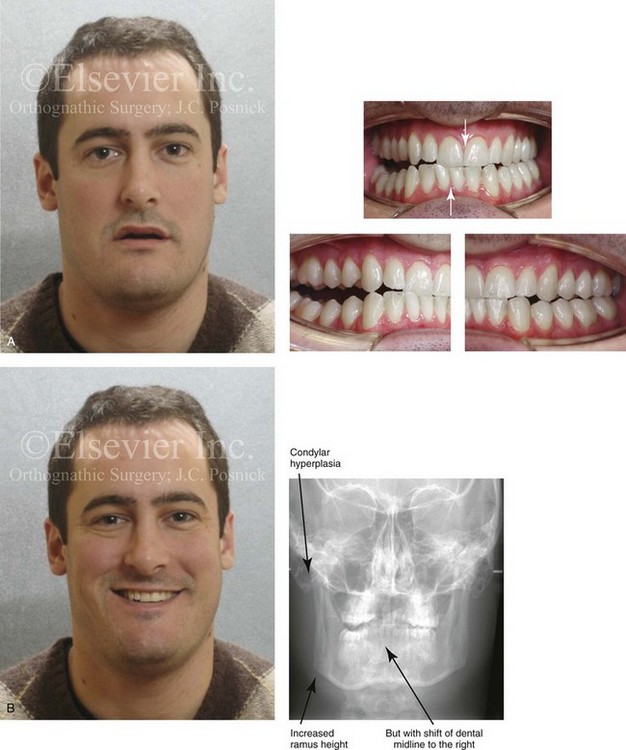

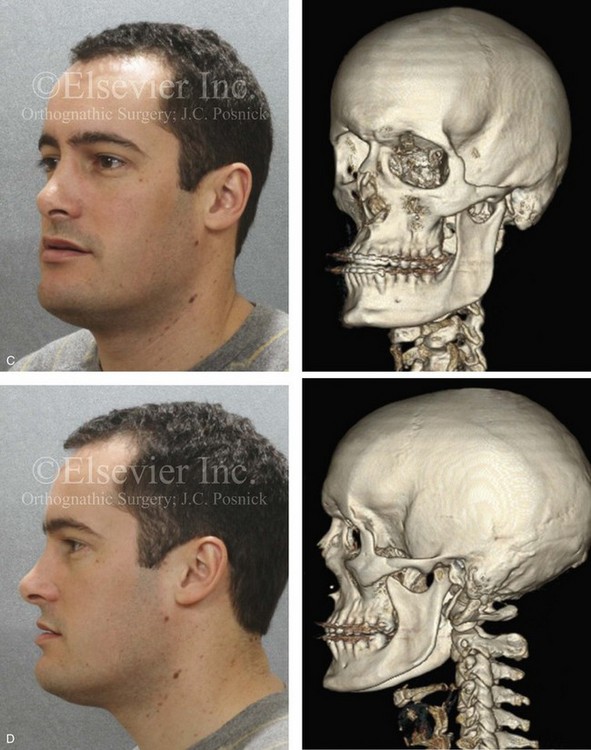

Figure 22-4 A man in his mid 20s with an atypical hybrid form of an asymmetric mandibular excess growth pattern on the right is shown without treatment intervention. A, Frontal facial view in repose. Occlusal views are also shown. The mandibular dental midline is tipped to the right. B, Frontal facial view with smile. A posteroanterior cephalometric radiograph is also shown. C, Left facial oblique and CT scan views without intervention. D, Left profile and CT scan views without intervention. E, Right facial oblique and CT scan views without intervention. F, Right profile and CT scan views without intervention.

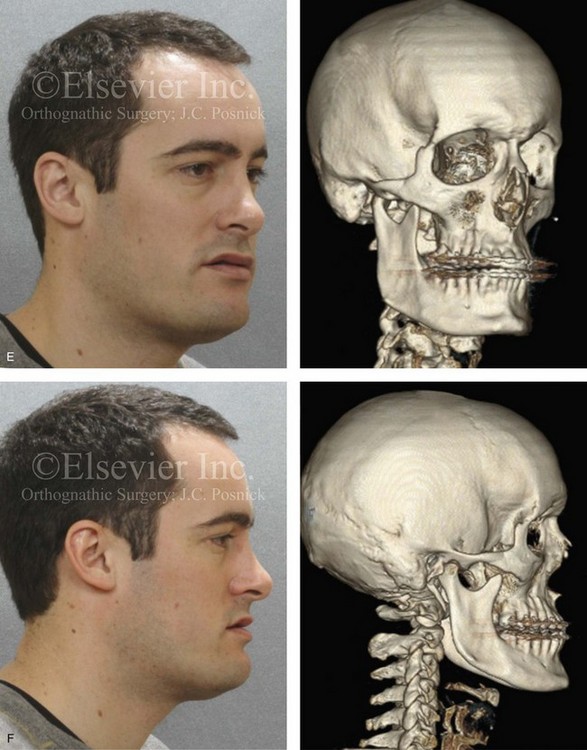

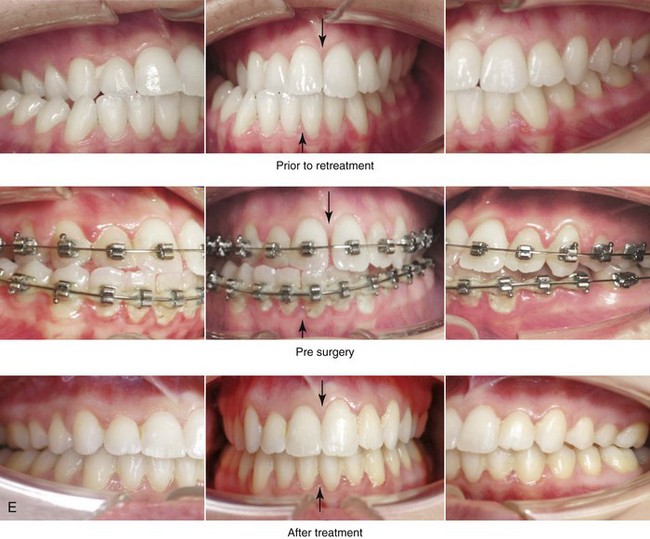

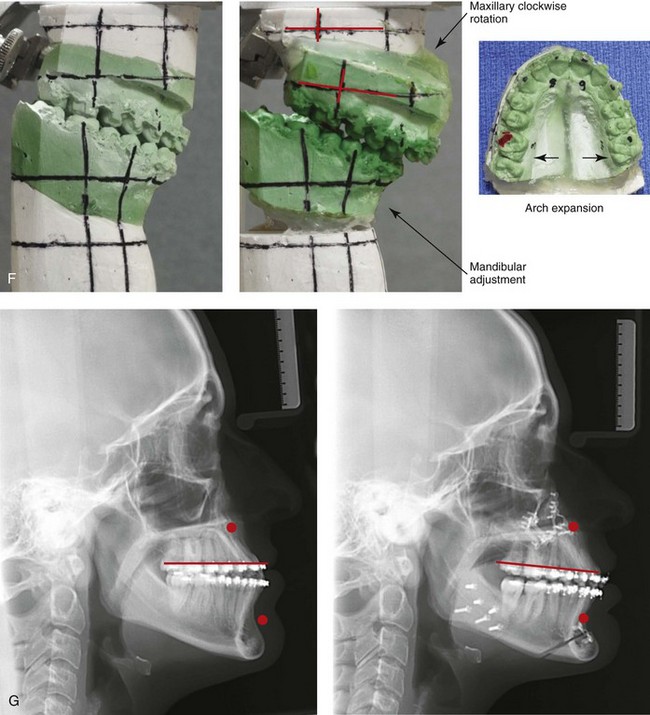

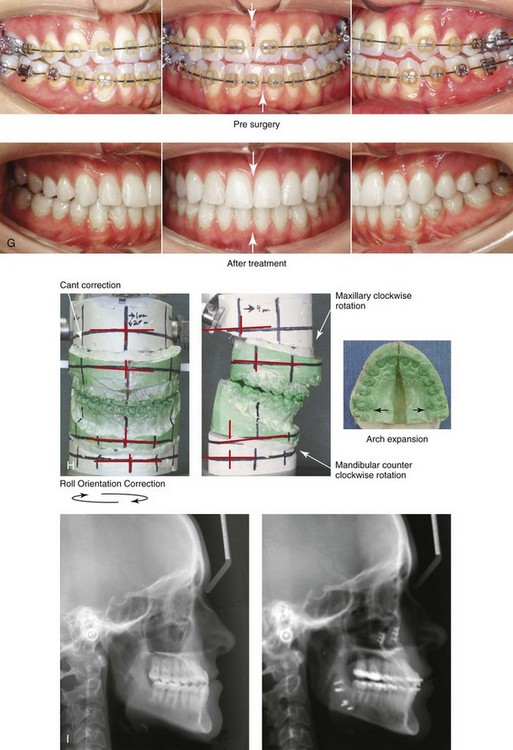

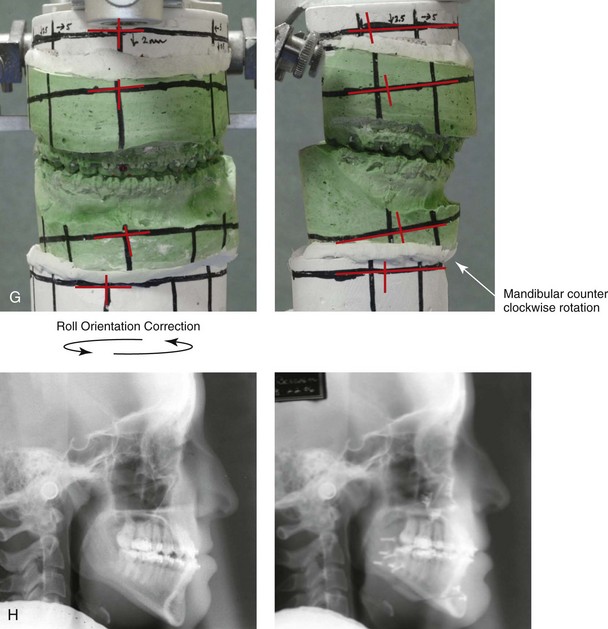

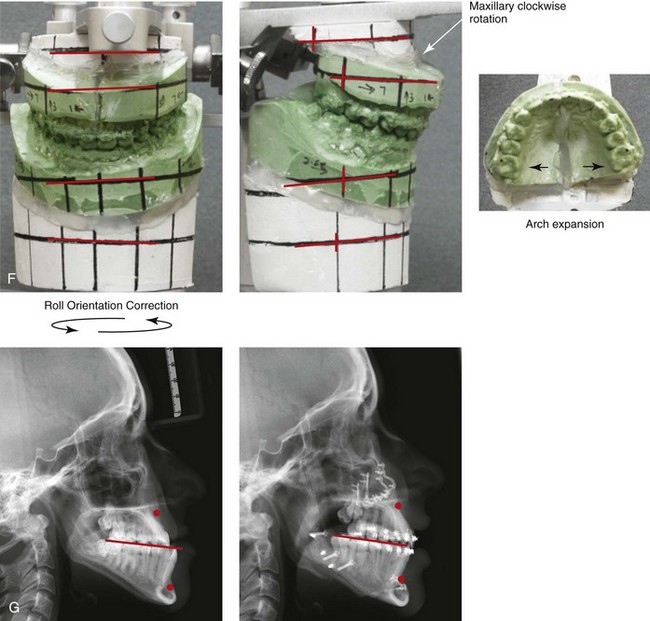

Figure 22-5 A 17-year-old female with hemimandibular hyperplasia of the left side and the typical facial and occlusal phenotype. She also has a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing. She underwent a comprehensive orthodontic and orthognathic surgical approach. Her procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (minimal advancement, cant correction, and arch expansion); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (cant correction and minimal horizontal advancement); left mandibular inferior border recontouring; osseous genioplasty (asymmetry correction); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. Note that asymmetry is present at the inferior borders before surgery and that there is much improvement afterward. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left facial oblique views before and after reconstruction. D, Right facial oblique views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before surgery and after reconstruction. F, Articulated dental models that indicate analytic surgical planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

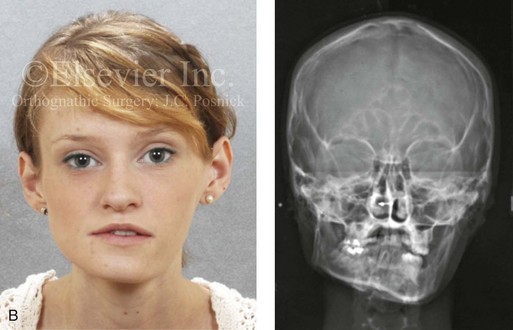

Figure 22-6 This is a 15-year-old girl who had been evaluated for routine orthodontic care when she was 12½ years old. At that time, she had not yet begun her menses or undergone a pubertal growth spurt. Routine orthodontics were initiated. By the time she was 15 years old (i.e., 2 years after menarche and a pubertal growth spurt), she developed an obvious asymmetric mandibular excess growth pattern due to right condylar overgrowth (Type II Hemimandibular Elongation). This resulted in both facial asymmetry and an asymmetric Angle Class III negative overjet with a posterior crossbite malocclusion. The mandibular dental midline and chin are shifted to the contralateral side. A, Facial and occlusal views when the patient was 12 years old. B, Facial and occlusal views when the patient was 15 years old. C, Panorex radiographs when the patient was 12 and 15 years old, respectively.

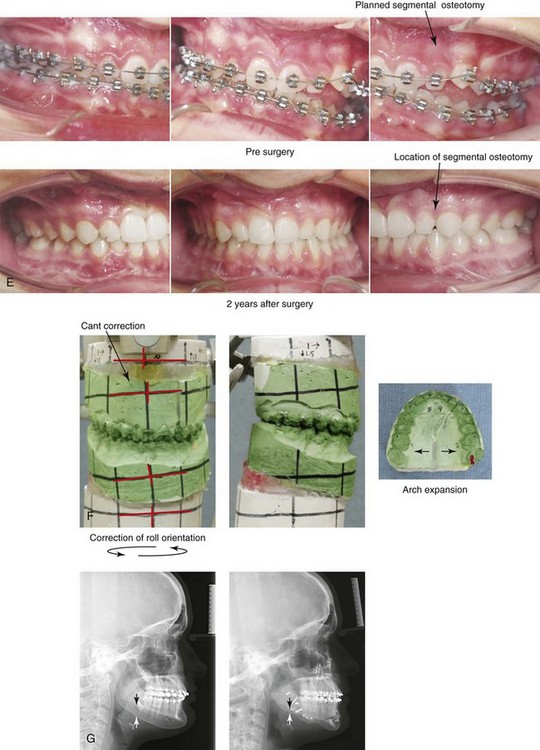

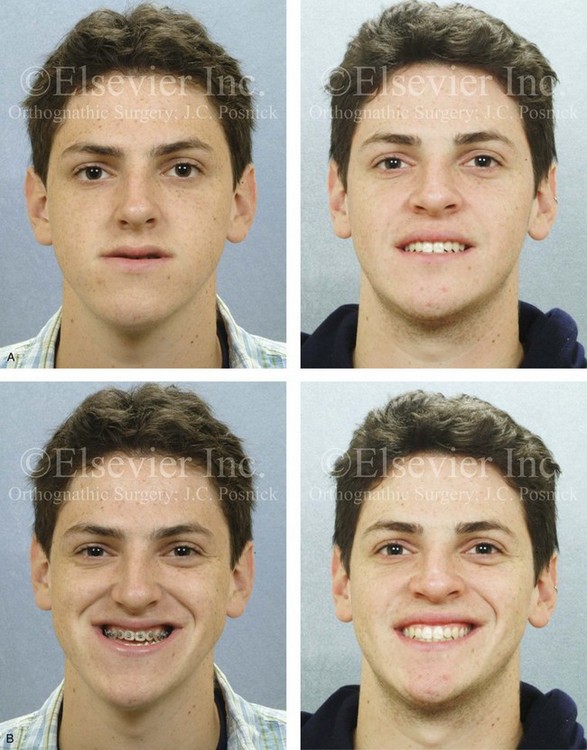

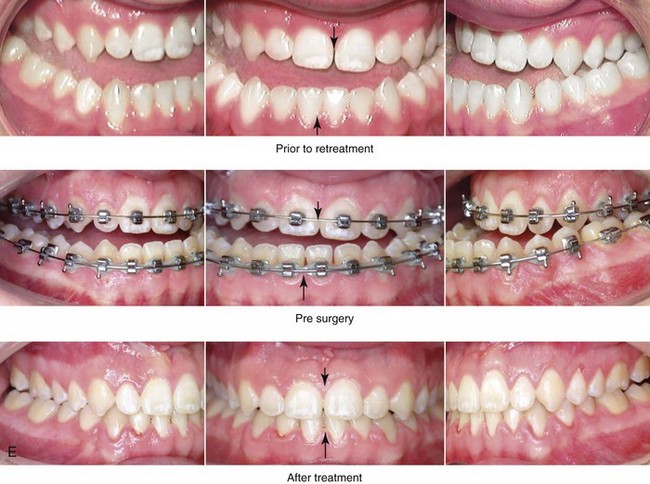

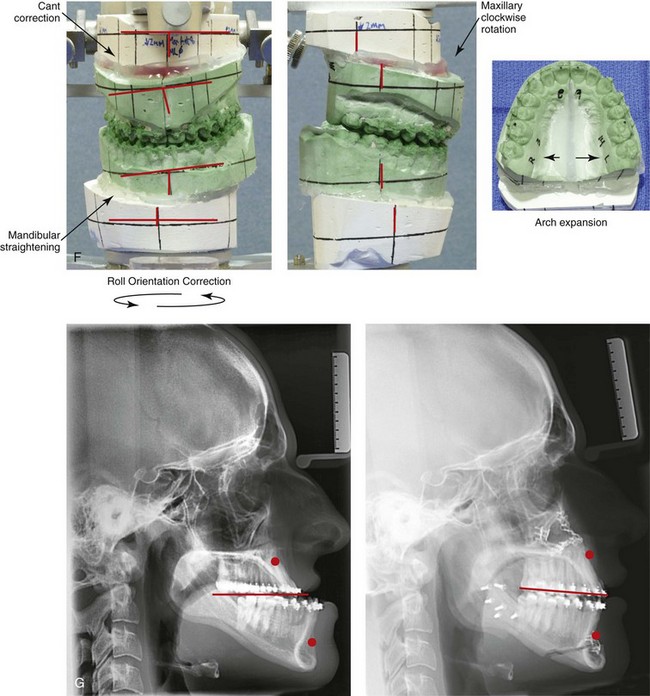

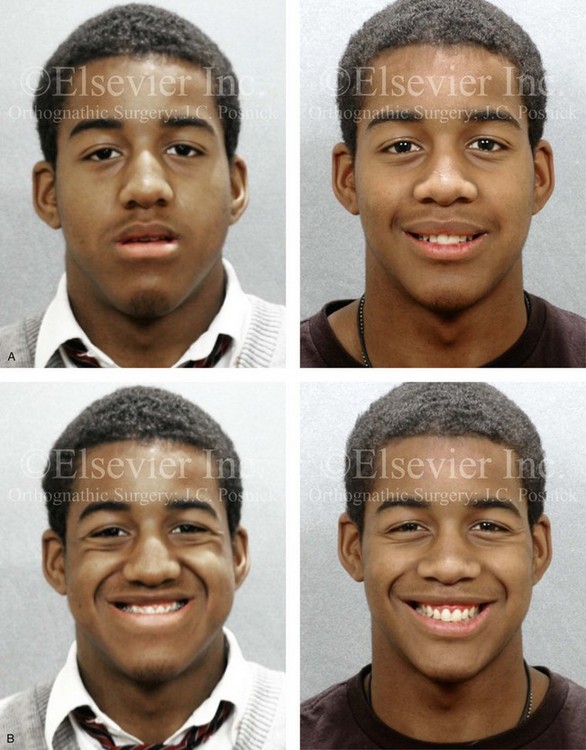

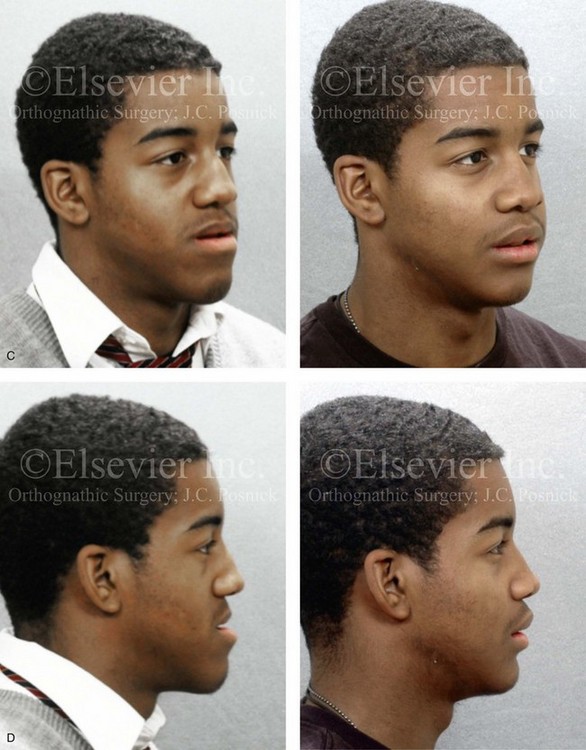

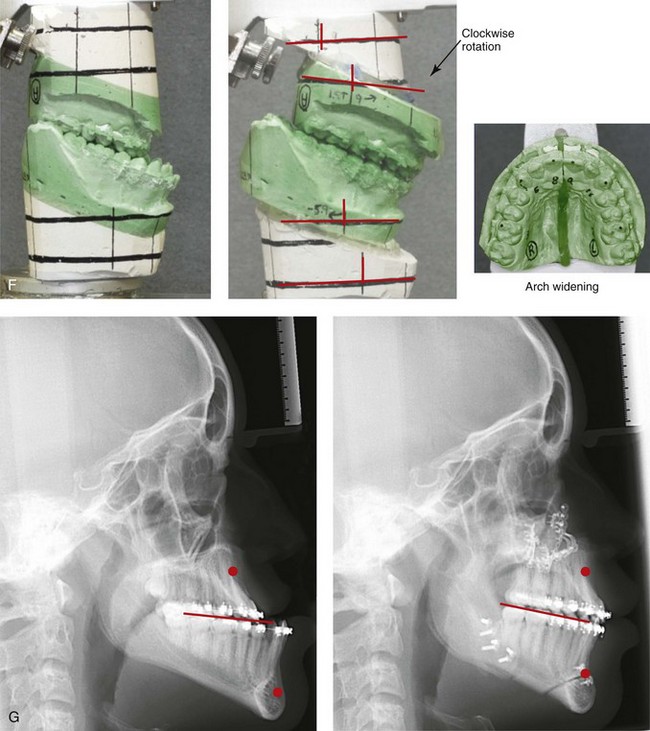

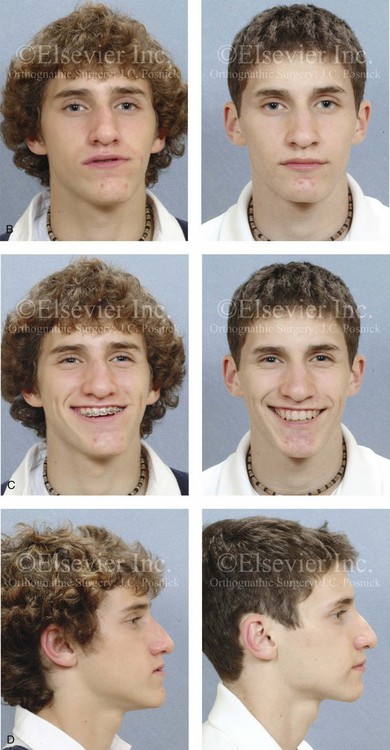

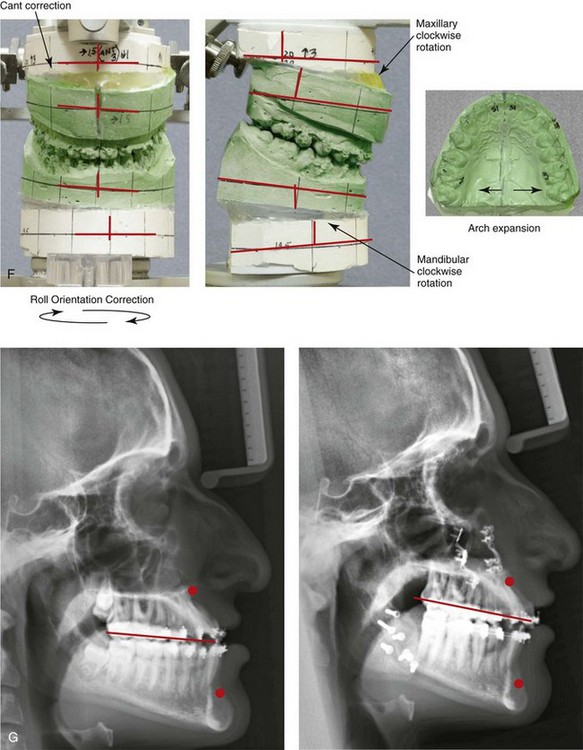

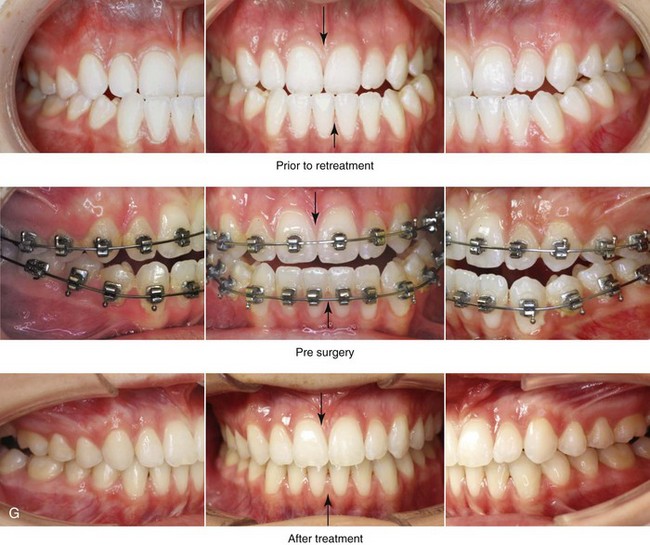

Figure 22-7 A 17-year-old boy with a diagnosis of left hemimandibular elongation is shown. This condition affects his chewing and speech articulation. The patient has a lifelong history of the obstruction of his nasal breathing. During his early teenage years, the patient underwent an initial phase of orthodontics, without success. He was referred for surgical evaluation and then underwent a combined redo orthodontic and surgical approach. With the relief of dental compensation, the patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, cant correction, arch expansion, and clockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (cant correction and mandibular straightening); septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction; and osseous genioplasty (straightening). A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontic decompensation, and 4 years after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

Figure 22-8 A 17-year-old male high school student was referred by his orthodontist for surgical evaluation. His asymmetric Class III negative overjet anterior open-bite malocclusion was consistent with hemimandibular elongation. He required redo orthodontics and jaw surgery with a non-extraction approach. The patient had a lifelong history of nasal obstruction and consistent physical findings, so intranasal procedures were also required. With orthodontic decompensation complete, the patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (arch expansion, horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, and clockwise rotation); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal set-back); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after the completion of treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment. Note the improved A-point to B-point relationship that has been achieved through maxillary clockwise rotation.

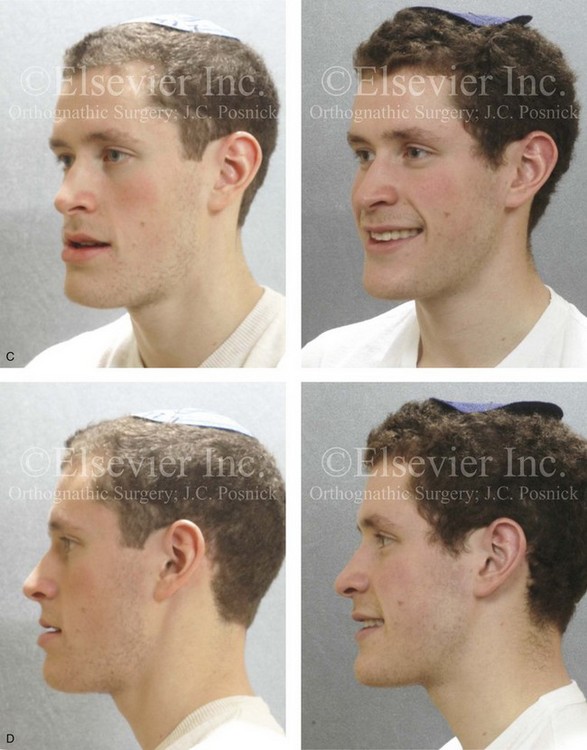

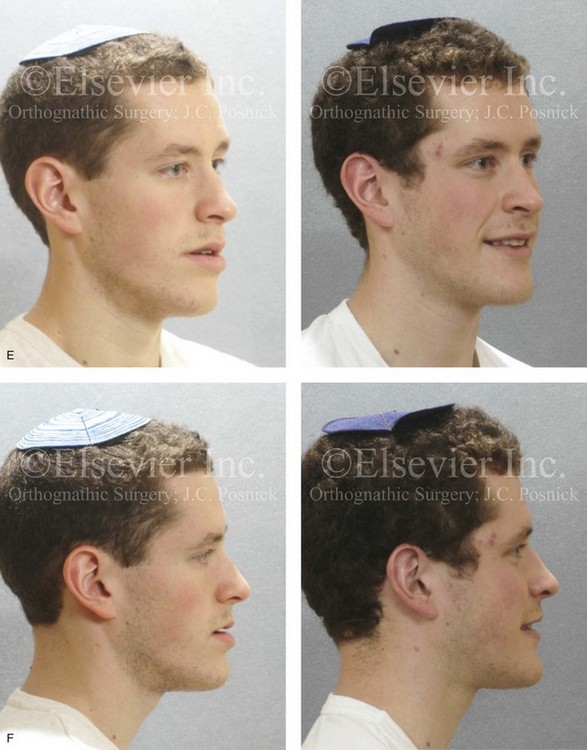

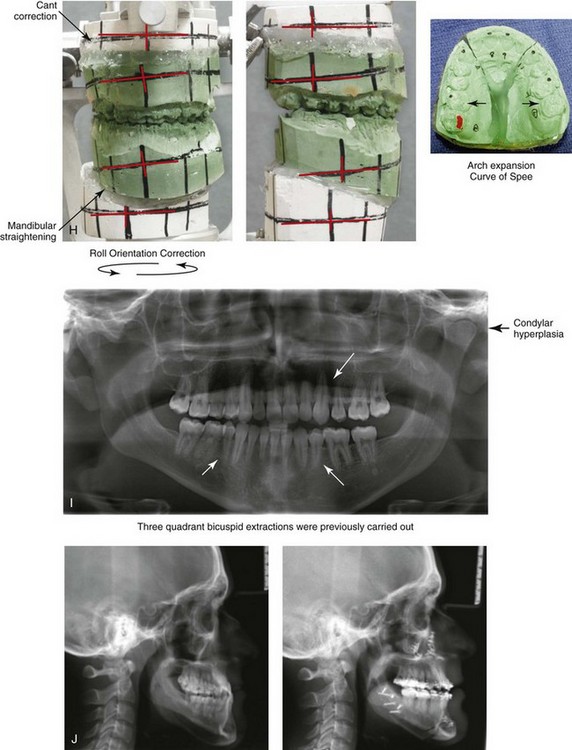

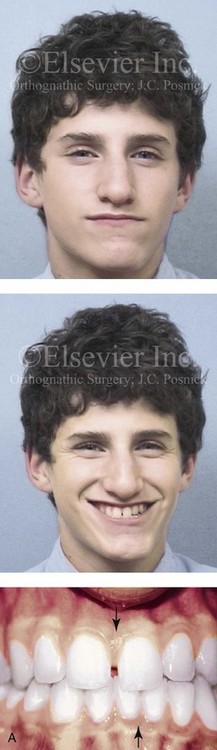

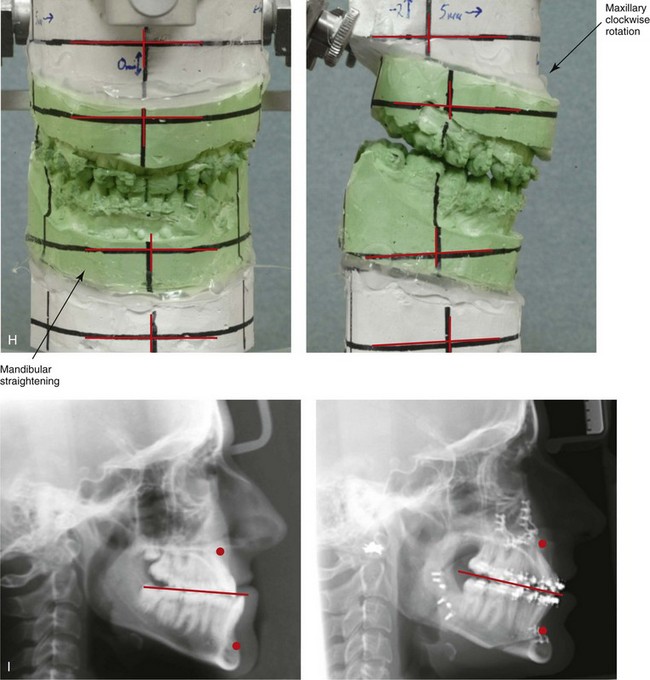

Figure 22-9 A 20-year-old man with left side hemimandibular elongation is shown. During his teenage years, he underwent attempted growth modification and orthodontic camouflage that included the removal of three bicuspids, without success. He had a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing. He was referred to this surgeon for evaluation and agreed to a comprehensive redo orthodontic and orthognathic approach. With the relief of dental compensation, his surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (minimal advancement, vertical adjustment, cant correction, arch expansion, and the correction of the curve of Spee); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening and asymmetric correction); osseous genioplasty (asymmetry improvement); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Left profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Right oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. F, Right profile views before and after reconstruction. G, Occlusal views before retreatment, after orthodontic decompensation, and after treatment. Note that the left mandibular second molar and the right maxillary second molar are unopposed; this is a result of the orthodontic extraction pattern. H, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. I, Panorex radiograph taken before retreatment that indicates left condyle hyperplasia and missing bicuspids in three quadrants. J, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

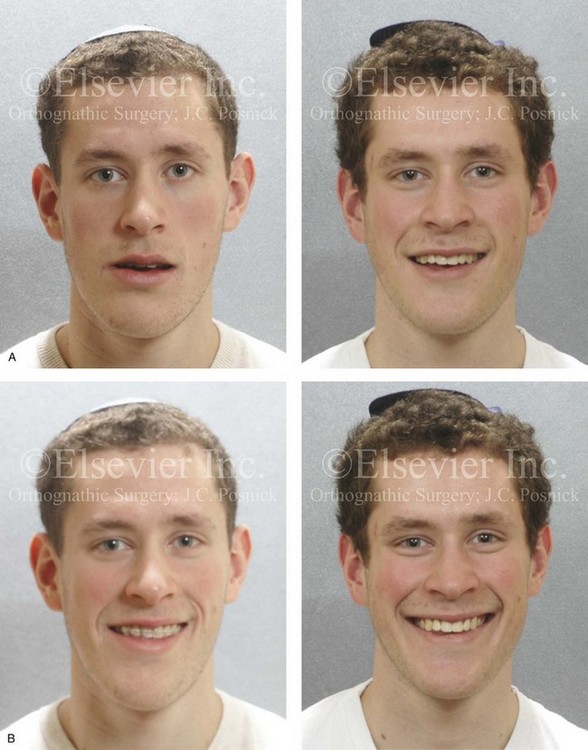

Figure 22-10 A teenaged boy with right side hemimandibular elongation. When he was between 10 and 14 years old, he was treated with growth modification attempts and then orthodontic camouflage. His overjet improved at the expense of the dental compensation, and the facial deformity remained. He was referred to this surgeon, who recommended stopping active treatment until the patient was skeletally mature. When he was 17 years old, he underwent redo orthodontics and an orthognathic approach. The orthodontics were carried out without extractions, which left the maxillary incisors procumbent. Clockwise rotation of the maxillomandibular complex as part of the orthognathic correction was helpful to overcome the facial disharmony. The patient’s surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (cant correction, horizontal advancement, clockwise rotation, arch expansion, and vertical lengthening); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening and clockwise rotation); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Facial and occlusal views when the patient was 14 years old, after failed growth modification and orthodontic camouflage. B, Facial views in repose before and after reconstruction. C, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views when the patient was 14 years old just after the removal of orthodontics appliances, with retreatment in preparation for surgery, and after reconstruction. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction. Clockwise rotation of the maxillomandibular complex was helpful to improve the A-point to B-point relationship, despite maxillary incisor procumbancy.

Figure 22-11 A 17-year-old girl with right side hemimandibular elongation. When she was between 10 and 14 years old, she was treated with growth modification and orthodontic camouflage techniques. She was referred to this surgeon when she was 17 years old to address her facial asymmetry and malocclusion. She underwent redo orthodontics to decompensate the arches as well as an orthognathic approach. Her surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement and clockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Left profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Right oblique views before and after reconstruction. F, Right profile views before and after reconstruction. G, Occlusal views before retreatment, in preparation for surgery, and after reconstruction. H, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. I, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

Figure 22-12 A 25-year-old woman with left side hemimandibular elongation. She was treated with growth modification and then orthodontic camouflage earlier in life, without success. She was referred to this surgeon and underwent redo orthodontics to decompensate the arches as well as an orthognathic approach. Lifelong nasal obstruction and intranasal examination confirmed the need for septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. The orthodontics were carried out without extractions, which left the maxillary incisors procumbent. Clockwise rotation of the maxilla as part of the orthognathic correction was helpful to overcome this problem and to improve the A-point to B-point relationship. Her surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (cant correction, horizontal advancement, clockwise rotation, and arch expansion); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Facial views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, in preparation for surgery, and after reconstruction. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

Figure 22-13 A 20-year-old woman with right side hemimandibular elongation. She was treated with orthodontic camouflage techniques, without success. She was referred to this surgeon and underwent an orthognathic and redo orthodontic approach. Her surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, clockwise rotation, and arch expansion); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (straightening and asymmetric correction); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Facial views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left oblique views before and after reconstruction. D, Left profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Right oblique views before and after reconstruction. F, Right profile views before and after reconstruction. G, Occlusal views in preparation for surgery and after reconstruction. H, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. I, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction. Clockwise rotation of the maxilla was helpful to improve the A-point to B-point relationship.

Figure 22-14 A 17-year-old girl with left side hemimandibular elongation. Earlier in her life, she was treated with growth modification and orthodontic camouflage techniques, without success. She also has a lifelong history of nasal obstruction. She was referred to this surgeon and underwent redo orthodontics and an orthognathic approach. Her surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (cant correction and horizontal advancement); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening); osseous genioplasty (minimal horizontal advancement); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Facial views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Right oblique views before and after reconstruction. E, Profile views before and after reconstruction. F, Occlusal views before retreatment, in preparation for surgery, and after reconstruction. Note that the maxillary and mandible dental midlines are improved but not fully corrected. G, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. H, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

Obwegeser also stated that these two pure forms of dentofacial deformity may present as a spectrum.23–25,68–91 He called these two pure dentofacial deformities Type I or hemimandibular hyperplasia and Type II or hemimandibular elongation. Obwegeser hypothesized that the steering mechanism for the growth of these two distinct mandibular anomalies is located entirely within the cartilaginous zone of the condylar head. This was proven to him by the fact that, whenever a very rapidly developing mandibular overgrowth (either Type I or Type II) was encountered, he was able to arrest the growth and prevent further deformity by completing a high condylar resection.

Raijmakers and colleagues carried out a meta-analysis to determine gender differences when it came to the diagnosis of asymmetric mandibular excess.101 Ten studies were reviewed, and these included a total of 275 affected patients. The meta-analysis showed a clear predominance of female patients in the study populations. The male and female patients had an equal distribution of left- and right-sided condylar overgrowth. The authors postulate that hormonal variations—especially of estrogen in women—may explain these differences. An alternative explanation put forth for this apparent female predilection is a difference in motivation between the sexes to seek the correction of their facial asymmetry (see Fig. 22-6).

Slootweg and Muller described four histologically different types of mandibular condylar hyperplasia.116 They proposed a classification system that is based on histologic criteria, and they divided hyperplastic condyles into four types, depending on the arrangement and morphology of the various layers of the condyle. These condylar layers were the fibrous articular layer; the undifferentiated mesenchyme proliferative layer; the transitional layer; and the hypertrophic cartilage layer.

Villanueva-Alcojol and colleagues attempted to correlate demographic and clinical presentations of condylar hyperplasia with the described histopathologic features and then with the associated scintigraphic and clinical findings after treatment with high condylectomy during the active phase.122 Interestingly, the authors were unable to find a correlation between the histologic type (as described by Slootweg and Muller116) and the uptake of the affected condyle on bone single photon emission computed tomography or between the patient’s age and his or her histologic type.

The preferred treatment to correct the dysmorphology for all forms of condylar hyperplasia is surgical including the repositioning and recontouring of the bones in combination with orthodontics to align the teeth.* The extent of treatment depends on the presenting dysmorphology and the status of condylar growth. If ongoing condylar growth is documented, then a form of high condylectomy should be considered to arrest progressive dysmorphology.20,21,40,42 High condylectomy (i.e., the removal of 4 mm to 5 mm of the condyle) and condylar shaving procedures (i.e., the removal of only 2 mm to 3 mm of the condyle) are options that are discussed in the literature. The documentation of cartilage islands that extend into the cancellous bone suggests that the pathology is not limited to the apparent cartilage surface. For this reason, some clinicians prefer the high condylectomy procedure, because it will also remove subcondylar bone; in theory, it will also more fully eliminate the potential of the growth center.

Hemimandibular Hyperplasia: Type I Condylar Hyperactivity

When hemimandibular hyperplasia is recognized in its active and progressive state, Obwegeser recommends a condylar shave to arrest the disease process and to prevent further progression.23–25,68–91 Another reason why some clinicians prefer the partial condylectomy procedure is that it can be used as a method to shorten the posterior facial height. When the phenotype is characterized by primary vertical overgrowth with minimal to no horizontal deviation of the mandible, it can simultaneously be an effective way to restore the morphology. If the deformity remains active and is allowed to reach its endpoint, then the restoration of ideal facial aesthetics is problematic. The objectives of the condylar shave procedure are to arrest any further abnormal growth on the affected side; to prevent continued secondary deformities of the maxilla, the nose, and the contralateral side of the mandible; and to arrest any additional malpositioning of the teeth. The problem with this approach is that secondary procedures to correct the facial skeleton are still required in most cases. It remains unclear just how much of a deformity will be aborted by an open-joint procedure.

Functional Aspects

• Articulation errors in speech may result if a significant malocclusion is present (see Chapter 8).

• Predictable chewing and swallowing difficulties will result if a significant posterior open-bite malocclusion is present (see Chapter 8).

• The ability to comfortably close the lips together and their position at rest may be negatively affected depending on the extent of jaw malposition and dental malocclusion.

• Depending on the extent of deformity, the individual with asymmetric mandibular excess is likely to experience self-esteem and body-image issues (see Chapter 7).

• Nasal airway obstruction as a result of a deviated septum and turbinate enlargement with increased nasal airway resistance may be present and should be ruled out (see Chapter 10).

• Detrimental long-term effects on the dentition and the periodontium caused by traumatic malocclusion, the displacement of teeth outside of the alveolar housing, or previous camouflage orthodontic treatment may occur (see Chapter 6).

• A higher-than-average incidence of TMD has been reported in this form of dentofacial deformity (see Chapter 9).

Clinical Characteristics

• This deformity should not be confused with hemifacial microsomia, because the soft-tissue envelope (including the external ear) is not hypoplastic on the affected side of the face.

• There is increased vertical height of the affected (ipsilateral) side of the face.

• The medial and downward shift of the ipsilateral mandible is most notable at the angle.

• There is a relative lateral and upward position of the contralateral mandible.

• The overall face has a “rotated” appearance.

• Mouth opening is without restriction.

• The ipsilateral corner of mouth is inferior but not posteriorly positioned.

• The cheek appears flat on the ipsilateral side.

• The width of the face on the ipsilateral side appears to be decreased.

• The maxilla is generally canted down on the ipsilateral side.

Dental Findings

• The crowns of the teeth on the contralateral side of the mandible tilt toward the ipsilateral side. They do so as a dental compensation to maintain occlusion with the opposing maxillary teeth, thereby avoiding crossbite.

• Lingual tilting of the mandibular alveolar ridge on the contralateral side is a secondary deformation as the (contralateral) lower jaw shifts lateral and assumes a superior position.

• The dental arches appear “twisted” by the slow process of three-dimensional growth distortion of the ipsilateral mandibular and the secondary deformations that occur in the contralateral side of the mandible and whole maxilla.

• If the ipsilateral excess mandibular growth is rapid, then the maxilla cannot respond at the same rate; this results in an ipsilateral posterior open bite.

• If the rate of ipsilateral excess mandibular growth is relatively slow, then maxillary dental hypereruption with secondary canting and the maintenance of occlusion are more likely.

• In most cases, the maxillary and mandibular dental midlines will closely match.

Radiographic Findings

• There is three-dimensional enlargement of the ipsilateral mandible, which terminates at the symphysis. The enlarged (ipsilateral) condyle also becomes “classically” deformed.

• The overall height of the body of the mandible is greater on the ipsilateral side.

• The inferior border and angle of the mandible are rounded on the ipsilateral side.

• Increased alveolar height between the inferior border and the root apices on the ipsilateral side is expected.

• The mandibular canal will be displaced downward on the ipsilateral side, often in close proximity to the inferior border.

Hemimandibular Elongation: Type II Condylar Hyperactivity

The dentofacial deformity called Type II hemimandibular elongation results in excessive growth on one side of the mandible without an overall three-dimensional increase in the volume of the whole affected side as seen with a Type I condition (i.e., hemimandibular hyperplasia; see Figs. 22-6 through 22-15). At the same time, hemimandibular elongation is not limited to just one aspect of the mandible. It results in a relative elongation (i.e. lateral shift) of all components of the ipsilateral lower jaw, including the condyle, the condylar neck, the ascending ramus, and the body. The condylar neck will be elongated and narrow, but the condylar head (i.e., the articulation of the temporomandibular joint [TMJ]) appears to be relatively normal in size and shape.

Figure 22-15 A 21-year-old woman with a diagnosis of left hemimandibular elongation; this affects her chewing and speech articulation. She also has a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing. During her early teenage years, the patient underwent an initial phase of orthodontics, without success. She was referred for surgical evaluation and then underwent a combined redo orthodontic and surgical approach. With the relief of dental compensation, the patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, cant correction, arch expansion, and clockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (cant correction and mandibular straightening); septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction; and osseous genioplasty (straightening). A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontic decompensation, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment. Note that the clockwise rotation of the maxilla was helpful to improve the A-point to B-point relationship as viewed in profile.

Obwegeser recognizes two distinct variations within the Type II hemimandibular elongation form of condylar hyperactivity.23,24,25,68–91 In the first subgroup (i.e., the “slender type”), there is an elongated hemimandible on the affected side as well as a morphologic “stretching” of the angle of the mandible. The distinguishing morphologic feature is an obtuse gonial angle as compared with the contralateral side. The second subgroup (i.e., the “non-slender type”) has an angle of the mandible that looks very much like the “normal” contralateral side and yet the whole (ipsilateral) mandible is clearly elongated.

To review, hemimandibular elongation is the preferred term for what has classically been referred to as “asymmetric mandibular excess.” Interestingly, the deformity has usually progressed and done its damage by the time of clinical presentation to the surgeon. For this reason, a condylar shave is rarely warranted. In general, these deformities can be reliably managed with standard orthognathic techniques carried out at skeletal maturity in conjunction with effective orthodontics to improve head and neck function and to enhance facial aesthetics (Fig. 22-6 through Fig. 22-14).

Functional Aspects

• Articulation errors in speech may result if a significant malocclusion is present (see Chapter 8).

• Chewing and swallowing difficulties resulting from the presenting malocclusion are typical (see Chapter 8).

• The ability to comfortably close the lips together and their position at rest will be negatively affected by the extent of jaw malposition and dental malocclusion.

• The individual with this jaw growth pattern is likely to experience self-esteem and body image issues directly related to the presenting facial asymmetry (see Chapter 7).

• Nasal airway obstruction as a result of a deviated septum and enlarged inferior turbinates with increased nasal airway resistance is likely present and should be ruled out (see Chapter 10).

• Detrimental long-term effects on the dentition and periodontium as a result of traumatic malocclusion, the displacement of the teeth outside of the alveolar housing, or previous camouflage orthodontic treatment may occur (see chapter 5 & 6).

• A higher-than-average incidence of temporomandibular disorder (TMD) has been reported with this anomalous pattern of dentofacial growth. Joint noise and discomfort on the ipsilateral side are not infrequent (see Chapter 9).

Clinical Characteristics

• The pogonion of the mandible and soft-tissue chin prominence are shifted to the contralateral side.

• The lower lip is in front of (i.e., anterior to) the upper lip; this is the reverse of normal.

• Vertical mouth opening is usually undisturbed.

• The ipsilateral corner of the mouth is usually lower and more anterior than the contralateral side (i.e., canting is present).

• The profile line may be harmonious, but it more likely gives the impression of mandibular prognathism.

• The soft-tissue cheek region appears fuller on the contralateral side.

• The prominence of the cheekbone appears to be deficient on the ipsilateral side.

• There is no apparent vertical height difference between the two sides of the face.

Dental Findings

• The ipsilateral molars are in Class III malocclusion.

• The contralateral molars may be in Class I or Class II malocclusion.

• A posterior crossbite on the contralateral side is typical.

• The mandibular dental midline is shifted to the contralateral side.

• Tilting of the lower anterior teeth with the incisal surfaces toward the ipsilateral side is typical.

• Retroinclination of the lower incisors is generally seen.

• Lingual inclination of the contralateral mandibular posterior teeth is typical.

• The maxilla is often canted downward and forward on the ipsilateral side.

Radiographic Findings

• Ascending ramus asymmetry from side to side is frequent.

• A thick cortical plate along the inferior border of the mandible on the ipsilateral side is frequent.

• The ipsilateral mandibular canal may appear to be lower positioned (i.e., closer to the inferior border), better defined (i.e., encased in cortical bone), and in close proximity to the roots of the teeth as compared with the contralateral side.

• The overall visual appearance and the measurable length of the mandible indicate elongation on the ipsilateral side.

• The ipsilateral angle of the mandible may be more obtuse (i.e., slender) as compared with the normal (contralateral) side.

• The ipsilateral condylar neck will be long, but the diameter is typically not increased.

• When viewed on a posteroanterior cephalometric radiograph, canting of the maxillary occlusal plane may be seen (i.e., downward and forward on the ipsilateral side).

• When viewed on a posteroanterior cephalometric radiograph, canting of mandibular plane is typically seen (i.e., downward and forward on the ipsilateral side).

Assessing Jaw Growth Maturity

Skeletal scintigraphy with a technetium bone scan is a useful method for the assessment of difficult growth-related diagnostic problems of the mandibular condyle.3,29,34,35,57,63,92,95,104 For patients with asymmetric mandibular excess, the state of residual growth may be clarified by the unequal ratio of uptake of technetium in each condylar head. Alternatively, an equal ratio of uptake shows that asymmetric growth has likely ceased. In difficult diagnostic cases, normal versus abnormal condylar growth can be further assessed by comparing the ratio of the uptake with the tabulated normative standards developed by Kaban and colleagues.18,19,43–46 The cessation of mandibular growth can be more or less predicted when the uptake ratios approach 0.70, which is the adult norm. Skeletal scintigraphy (i.e., bone scan) may be useful during the making of decisions that involve the timing and extent of treatment when residual condylar growth remains uncertain. After the cessation of growth, there will be no advantage to an open-joint procedure. In this case, the correction of the dentofacial deformity with the use of standard orthognathic techniques is indicated.5,107–109

High Partial Condylectomy Procedure for Active Condylar Hyperactivity

The successful treatment of asymmetric mandibular excess requires the cessation of growth before definitive surgical correction. Knowledge of whether the condition is still active is assessed at the condylar site.5,107–109 For the patient with hemimandibular elongation, the deformity has usually progressed and done its damage by the time of clinical presentation to the surgeon. In general, the presenting jaw deformities are best managed with standard orthognathic techniques that are carried out at skeletal maturity to improve both head and neck function and to enhance facial aesthetics. Alternatively, the hemimandibular hyperplasia deformity may be more gradual in its progression. In this case, if the condition is allowed to reach its endpoint, it may not be possible to achieve an ideal symmetric facial aesthetic result. A condylar shave procedure may be beneficial for the subgroup of patients with Type I hemimandibular hyperplasia to arrest ongoing abnormal growth on the affected side; to prevent further secondary deformities of the maxilla, the nose, and the contralateral side of the mandible; and to arrest the malpositioning of the teeth.20,21,40,42

Lippold and colleagues as well as other researchers have suggested that minimal harm occurs from a “high condylar shave.”51 Until recently, critical reviews of an invasive TMJ approach have not been forthcoming. Saridin and colleagues completed an evaluation of temporomandibular function after high partial condylectomy in a consecutive series of individuals with unilateral condylar hyperplasia (N = 33).110 The study group included individuals with unilateral condylar hyperplasia whose conditions were considered to be active; in other words, the mandibular asymmetry appeared to be clinically progressive, and the bone scan was positive. The subjects then underwent high condylectomies (N = 33). The patients were compared with a control group that was matched for age and gender (N = 31). All patients and all members of the control group filled out a history questionnaire and underwent a clinical examination in accordance with the research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. The patients were studied for an average of 4.3 years after the condylectomy was carried out (range, 0.6 to 13.3 years). The results of the study indicate that patients with unilateral condylar hyperplasia who undergo condylectomy in an attempt to arrest progressive mandibular asymmetry will have more joint-related temporomandibular problems and a higher persistence of long-term pain as compared with age- and gender-matched controls.

Presurgical Orthodontic Treatment

Among patients who are affected by these mandibular excess growth patterns, orthodontic maneuvers that were carried out earlier during their lives to modify growth or as camouflage approaches to neutralize the occlusion should be overcome with further orthodontic mechanics before orthognathic surgery. Frequently seen scenarios include the following: (1) orthodontic overexpansion of the maxillary arch to correct crossbites; (2) hypereruption of the molars on one side and intrusion on the other side to correct canting; (3) lingual tipping of the mandibular molar or premolar crowns on the contralateral side and buccal tipping of the molar or premolar crowns on the ipsilateral side; and (4) retroclining of the lower anterior teeth to correct the overbite. All of these orthodontic techniques may have been tried with the hope of neutralizing the occlusion and avoiding surgery. These camouflage orthodontic mechanics hamper the preferred surgical positioning of the jaws to achieve maximum facial harmony, and they will also leave the occlusion prone to late relapse and the dentition susceptible to long-term periodontal breakdown (see Chapter 5).

In preparation for an orthognathic correction, the orthodontic treatment of each jaw should achieve the correct positioning of the teeth within the respective alveolar process (see Chapter 5). If this is accomplished, the clinicians can best achieve maximum mirror-image skeletal symmetry, Euclidian facial proportions, and a long-term stable occlusion with periodontal health (see Chapter 6).

Surgical Approach

The Influence of Chin Asymmetry on Perceived Facial Attractiveness

Naini and colleagues undertook an investigation with the objective of assessing how severe an asymmetry at the chin point would have to be to influence perceived attractiveness.64 Idealized two-dimensional frontal facial views were created with the use of computer software in which the chin point was altered from side to side in 5-mm increments from 0 mm to 25 mm. These images were then rated on a seven-point Likert scale by a preselected group of observers that included orthognathic patients before treatment, clinicians, and laypeople (n = 185 observers). The study confirmed that, in the frontal view, chin asymmetries of 10 mm or greater are perceived as being significant, whereas those of 5 mm or less largely go unnoticed. The greater the degree of asymmetry (i.e., >10 mm), the more noticed it will be by an observer and the greater the patient’s desire for correction. Both clinician and patient ratings were similar and found to be more critical than the ratings given by laypeople. The images that were considered the most attractive showed perfect bilateral symmetry of the chin region. The lowest-rated images showed the highest degrees of asymmetry of the chin. Combined vertical and horizontal asymmetries were rated slightly worse than horizontal asymmetry alone.

Hemimandibular Hyperplasia (Type I)

If the hemimandibular hyperplasia deformity remains active and is allowed to progress to its endpoint, it may not be possible to achieve an ideal symmetric facial aesthetic result. For this reason, a high condylar shave to arrest further abnormal growth on the affected side and to prevent ongoing secondary deformities (i.e., of the maxilla, nose, and contralateral side of the mandible; malpositioning of the teeth) should be considered if condylar hyperactivity remains, as described previously.20,21,40,42

Details of the definitive maxillofacial reconstruction will depend on the patient-specific morphologic findings (see Figs. 22-2 through 22-5).30,32,97,98,105 A wide spectrum of three-dimensional maxillofacial distortions caused by the primary anomaly and the secondary deformities is expected. In addition to standard techniques (i.e., Le Fort I osteotomy in segments, sagittal split ramus osteotomies of the mandible, osteotomy of the chin), mandibular inferior border recontouring will often be beneficial (see Chapter 12). The recontouring includes inferior border resection and rotary drill bur modification from the angle of the mandible to the chin on the ipsilateral side, as indicated. Inferior border augmentation on the contralateral side is not usually recommended because, over time, visible irregularities on the grafted side can easily occur after partial graft resorption. Segmentation of the maxilla (i.e., into two or three pieces) is also generally required to correct the cant and the arch form.

Hemimandibular Elongation (Type II)

The deformities of hemimandibular elongation are best managed with standard orthognathic techniques carried out at skeletal maturity to improve both head and neck function and to enhance facial aesthetics (see Figs. 22-6 through 22-14). This will include, at a minimum, sagittal split ramus osteotomies of the mandible. If the maxilla is secondarily deformed (i.e., canted, with a shift of the dental midline and an altered arch form), a Le Fort I osteotomy with three-dimensional repositioning is also required. An oblique osteotomy of the chin will likely further improve facial symmetry and proportions (see Chapter 12). The need for a high condylar shave to arrest growth remains limited, and this procedure is only considered in the presence of documented progressive active disease at the time of diagnosis.

Complications, Informed Consent, and Patient Education

Orthodontists and surgeons are frequently asked to evaluate jaw disharmonies and malpositioned teeth and then to attempt to alter nature’s events. With an understanding of the natural progression of the uncorrected asymmetric mandibular excess growth anomaly and with knowledge of how specific interventions will affect head and neck function and facial aesthetics, predictable results are generally achieved. Complications and patient dissatisfaction will always occur in a small percentage of individuals. In the setting of asymmetric mandibular excess, obtaining the desired occlusion is more or less predictable. The expected outcome is an improvement in the facial asymmetry with persistent minor discrepancies. The clinician’s ability to communicate the potential risks, complications, alternative approaches, and expected results of the recommended treatment to the patient and the patient’s family is essential to the achievement of a favorable outcome. When the patient, the family, and all treating clinicians are fully informed, shared responsibility for the treatment result is more likely (see Chapter 16).

Malocclusion after Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

There are inherent biologic challenges to the orthodontic movement of the teeth within the alveolar process and to the surgical repositioning of the jaws or jaw segments in the individual with an asymmetric mandibular excess growth anomaly. This includes the technical aspects of the repositioning, the initial healing requirements, and the difficulties associated with the long-term maintenance of the mechanically relocated teeth, jaws, and jaw segments. When following sound biomechanical and aesthetic principles, clinicians carry out orthodontic treatments and surgical procedures; in most cases, the results are effectively maintained. Potential intraoperative technical difficulties associated with sagittal split ramus osteotomies of the mandible and maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy can result in immediate early malocclusion, but these problems are generally preventable (see Chapter 17). In the teenager, timing surgery to limit concern about ongoing mandibular growth afterward is more problematic with asymmetric mandibular excess than with most other patterns of dentofacial deformity; this is discussed in more detail earlier in this chapter. All of these factors must be taken into account to achieve and then maintain the desired results.

Temporomandibular Disorders: The Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

It is estimated that an average of 32% of the population report at least one symptom of TMD, whereas an average of 55% demonstrate at least one clinical sign. TMD includes various symptoms and signs of the TMJs, the masticatory muscles, and the related structures. The symptoms and signs may include a spectrum of referred head and neck pain; joint noise (e.g., popping, clicking, crepitus); reduced or altered mandibular movements caused by muscle spasm or disc displacement with or without reduction; condylar head erosion; and pain on direct palpation of either of the TMJs or the masticatory muscles. Occlusal factors (i.e., degrees of malocclusion) are often claimed to be associated with TMD. Asymmetric mandibular excess is associated with TMD more frequently than many other dentofacial deformities. The correction of the presenting jaw deformity and malocclusion through effective orthodontics and orthognathic surgery may relieve symptoms and signs of TMD in some patients, but this is not predictable for each individual patient. As stated earlier in this chapter, Saridin and colleagues found that the completion of a partial condylectomy on the ipsilateral side was associated with a higher incidence of TMD (see Chapter 9).110 This should give the clinician pause before he or she agrees to perform a condylectomy procedure.

References

1. Adams, SS. A case of hemihypertrophy (giant growth). Arch Pediatr. 1894; 2:901.

2. Angle, EH. Treatment of malocclusion of the teeth: Angle’s system, ed 7. Philadelphia: SS White; 1907.

3. Beirne, OR, Leake, DL. Technetium-99m pyrophosphate uptake in a case of unilateral condylar hyperplasia. J Oral Surg. 1980; 38:385.

4. Benoist, M, LePesteur, J. Considerations sure le bilan preoperatoire des laterognathies mandibulaires. Rev Stomatol. 1976; 77:96.

5. Björk, A. Variations in the growth pattern of the human mandible: Longitudinal radiographic study by the implant method. J Dent Res Suppl. 1963; 42:400–411.

6. Bloomquist, K, Hogeman, KE. Benign unilateral hyperplasia of mandibular condyle: Report of eight cases. Acta Chir Scand. 1963; 126:414.

7. de Bont, LG, Blankestijn, J, Panders, AK, Vermey, A. Unilateral condylar hyperplasia combined with synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: Report of a case. J Maxillofac Surg. 1985; 13:32–36.

8. Brami, S, Lamarche, JP, Souyris, F. Treatment of facial asymmetries by one-stage maxillary and mandibular bilateral osteotomies. Int J Oral Surg. 1974; 3:239.

9. Bruce, RA, Hayward, JR. Condylar hyperplasia and mandibular asymmetry: A review. J Oral Surg. 1968; 26:281–290.

10. Buchner, A, David, R, Temkin, D. Unilateral enlargement of the masseter muscle. Int J Oral Surg. 1979; 8:140.

11. Burchfield, D, Escobar, V. Familial facial asymmetry (autosomal dominant hemihypertrophy?). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980; 50:321.

12. Norman, JE, Painter, DM. Hyperplasia of the mandibular condyle. A historical review of important early cases with a presentation and analysis of twelve patients. J Maxillofac Surg. 1980; 8:161–175.

13. Cernea, P. Unilateral hypertrophy of the mandibular condyle. Trans Int Conf Oral Surg. 1967; 255–257.

14. Chen, YR, Bendor-Samuel, RL, Huang, C-S. Hemimandibular hyperplasia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 97:730.

15. Chen, YR, Lo, LJ, Kyutoku, S, et al. Facial midline and symmetry: Modified face bow. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 90:126.

16. Chierici, G, Harvold, EP, Dawson, WJ. Primate experiments on facial asymmetry. J Dent Res. 1970; 49:847.

17. Choung, PH. Surgical correction of asymmetric mandibular excess. Taehan Chikkwa Uisa Hyophoe Chi. 1985; 23:1057.

18. Cisneros, GJ. The use of bone seeking radiopharmaceutical uptake in the assessment of facial growth and development [thesis]. Harvard University; 1982.

19. Cisneros, GJ, Kaban, LB. Computerized skeletal scintigraphy for assessment of mandibular asymmetry. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984; 42:513–520.

20. Delaire, J, Gaillard, A, Tulasne, JF. La place de la condylectomie dans le traitment des hypercondyles. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1983; 84:11–18.

21. Delaire, J. Le role du condyle la croissance de la machoire inferieur et dans l’equilibie de la face. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1990; 91:179–192.

22. Dingman, RO, Grabb, WC. Mandibular laterognathism. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1963; 31:563.

23. Egyedi, P, Obwegeser, H. Zur operativen zungenverkleinerung. Dtsch Zahn Mund Kiefrehlkd. 1964; 41:16–25.

24. Egyedi, P. Etiology of condylar hyperplasia. Aust Dent J. 1969; 14:12–17.

25. Egyedi, P. Hyperplasia van de condylus mandibulae. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1974; 118:1593.

26. Ferguson, JW. Definitive surgical correction of the deformity resulting from hemimandibular hyperplasia. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005; 33:150–157.

27. Forsberg, CT, Burstone, CJ, Hanley, KJ. Diagnosis and treatment planning of skeletal asymmetry with the submental-vertical radiograph. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1984; 85:224.

28. Gordeeff, A, Mercier, J, Delaire, J. L’hypercondyle mandibulaire. Ses different aspects cliniques et son traitement. Acta Stomatol Belg. 1988; 85:269–276.

29. Gray, RJM, Sloan, P, Quale, AA, Carter, DH. Histopathological and scintigraphic features of condylar hyperplasia. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990; 19:65–71.

30. Grummons, DC, Kappeyne van de Coppello, MA. A frontal asymmetry analysis. J Clin Orthod. 1987; 21:448.

31. Grunert, J, Krenhal, CH, Furtenbach, M. Vergleich myofuntioneller befunde bei patienten mit und ohne rezidiv nach progenie-operationen. Z Stomatol. 1990; 87:261–271.

32. Hall, HD. An improved method for treatment of facial asymmetry secondary to jaw deformity. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984; 42:673.

33. Hampf, GA, Tasanen, A, Nordling, S. Surgery in mandibular condylar hyperplasia. J Maxillofac Surg. 1985; 13:74–78.

34. Harris, SA, Quayle, AA, Testa, HJ. Radionuclide bone scanning in the diagnosis and management of condylar hyperplasia. Nucl Med Commun. 1984; 5:373.

35. Henderson, MJ, Wastie, ML, Bromige, M, et al. Technetium-99m bone scintigraphy and mandibular condylar hyperplasia. Clin Radiol. 1990; 41:411.

36. Hinds, ED, Reid, LC, Burch, RJ. Classification and management of mandibular asymmetry. Am J Surg. 1960; 100:825.

37. Hovinga, J, Kraal, ER, Roorda, LAM. Difficulties in and indications for the treatment of facial asymmetry. Int J Oral Surg. 1974; 3:234.

38. Hyckel, P, Erler, U, Muller, P. Unilateral hyperplasia of the TMJ condyle [German]. Dtsch Z Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 1991; 15:42–50.

39. Jacobs, FJ, Rafel, SS, Weiss, B. Correction of asymmetric mandibular prognathism by unilateral osteotomy. J Oral Surg. 1953; 11:42.

40. Jaquemaire, D, Delaire, J. L’hypercondylie mandibulaire. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1983; 84:5–10.

41. Jonck, LM. Facial asymmetry and condylar hyperplasia. J Oral Surg. 1975; 40:567.

42. Jonck, LM. Condylar hyperplasia: A case for early treatment. Int J Oral Surg. 1981; 10:154.

43. Kaban, LB, Cisneros, GJ, Heymann, S, Treves, ST. Assessment of mandibular growth by skeletal scintigraphy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982; 40:18–22.

44. Kaban, LB. Skeletal scintigraphy for assessment of mandibular growth and asymmetry. In: Treves ST, ed. Pediatric nuclear medicine. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985:49.

45. Kaban, LB. Congenital and acquired growth abnormalities of the temporomandibular joint. In: Keith DA, ed. Surgery of the temporomandibular joint. London: Blackwell Scientific; 1992:84–115.

46. Kaban, LB, Treves, ST, Pogrel, MA, Hattner, RS. Skeletal scintigraphy for assessment of mandibular growth and asymmetry. In: Treves ST, ed. Pediatric nuclear medicine. ed 2. New York, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 1995:316–327.

47. Kaneda, T, Torii, S, Yamashita, T, et al. Giant osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982; 40:818.

48. Keller, E, Jackson, IT, Marsh, WR, et al. Mandibular asymmetry associated with congenital muscular torticollis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1986; 61:216.

49. Kessel, LJ. Condylar hyperplasia: A case report. Br J Oral Surg. 1969; 7:124.

50. Lineaweaver, W, Vargervik, K, Tomer, BS, Ousterhout, DK. Posttraumatic condylar hyperplasia. Ann Plast Surg. 1989; 22:163–172.

51. Lippold, C, Kruse-Losler, B, Danesh, G, et al. Treatment of hemimandibular hyperplasia: The biological basis of condylectomy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 45:353–360.

52. Luhr, HG. Zur stabilen osteosynthese bei unterkiefer–frakturen. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z. 1968; 23:754.

53. Luhr, HG. Skelettverlagernde operationen zur harmonisierung des gesichtsprofils––probleme der stabilen fixation von osteotomiesegmenten. In: von Pfeifer G, ed. Die asthetik von form und funktion in der plastischen und wiederherstellungschirurgie. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1985:87.

54. MacIntosh, RB. Treatment of condylar hyperplasia of the mandible using unilateral ramus osteotomies [discussion]. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996; 54:1169.

55. Magnusson, T, Ahlborg, G, Svartz, K. Function of the masticatory system in 20 patients with mandibular hypo- or hyperplasia after correction by a sagittal split osteotomy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990; 19:289.

56. Martis, C, Raraboula, I, Zazaridis, N. Severe unilateral condylar hyperplasia corrected by modified sagittal split osteotomy: Report of a case. J Oral Surg. 1979; 37:835.

57. Matteson, SR, Proffit, WR, Terry, BC, et al. Bone scanning with 99 m technetium phosphate to assess condylar hyperplasia. Report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985; 60:356–367.

58. Mercier, P. Mandibular asymmetry: Proposed classification and an analysis of two cases. J Can Dent Assoc. 1969; 35:146–153.

59. Mizuno, A, Motegi, K. Treatment of an asymmetric mandibular prognathism in an acromegalic patient. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988; 46:314.

60. Mizuno, A, Nakamura, T, Motegi, K, Shirasawa, H. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: Report of a case and review of the Japanese literature. Int J Oral Surg. 1983; 12:221.

61. Motamedi, MHK. Treatment of condylar hyperplasia of the mandible using unilateral ramus osteotomies. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996; 54:1161.

62. Müller, H. Unilateral condylar hyperplasia and acromegaly. J Maxillofac Surg. 1979; 7:73–76.

63. Murray, IP, Ford, JC. Tc-99m medronate scintigraphy in mandibular condylar hyperplasia. Clin Nucl Med. 1982; 7:474.

64. Naini, FB, Donaldson, AA, McDonald, F, et al. Assessing the influence of asymmetry affecting the mandible and chin point on perceived attractiveness in the orthognathic patient, clinician, and layperson. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 70:192–206.

65. Nitzan, DW, Katsnelson, A, Bermanis, I, et al. The clinical characteristics of condylar hyperplasia: Experience with 61 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008; 66(2):312–318.

66. Norman, JE, Painter, DM. Hyperplasia of the mandibular condyle: A historical review of important early cases with a presentation and analysis of twelve patients. J Maxillofac Surg. 1980; 8:161.

67. Oberg, T, Fajers, CM, Lysell, G, Friberg, U. Unilateral hyperplasia of the mandibular condyle process. A histological, microradiographic and autoradiographic examination of one case. Acta Odontol Scand. 1962; 20:485–504.

68. Obwegeser, HL. Ueber eine einfache methode der freihandigen drahtschienung von kieferbruchen. Oesterr Z Stomatol. 1952; 49:652–670.

69. Obwegeser, HL. In Trauner R, Obwegeser H, editors: Zur operationstechnik bei der progenie and anderen underkieferanomalien. Dtsch Zahn Mund Kieferhlkd. 1955; 23:11–26.

70. Obwegeser, HL. Surgical procedures to correct mandibular prognathism and reshaping of the chin. In Trauner R, Obwegeser H, editors: The surgical correction of mandibular prognathism and retrognathia with consideration of genioplasty. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1957; 10:677–689.

71. Obwegeser, HL. Die Kinnvergrosserung. Oesterr Z Stomatol. 1958; 55:535–541.

72. Obwegeser, HL. Cirugia del “modex apertus. ”. Rev Asoc Odont Argent. 1962; 50:430–441.

73. Obwegeser, HL, Egyedi, P. Zur operativen zungenverkleinerung. Dtsch Zahn Mund Kieferhlkd. 1964; 41:16–25.

74. Obwegeser, HL. Der offene biss in chirurgischer sicht. Schweitz Monatschr Zahnhlkd. 1964; 74:668–687.

75. Obwegeser, HL. Zur behandlung der veralteten oberkieferfracturen. Fortschr Kiefer Gesichtschir. 1967; 12:126–131.

76. Obwegeser, HL. Die bewegung des unteren alveolarforstatzes zur korrektur von kieferstellungsanomalien: Part 1. Dtsch Z Zeitschrift. 1968; 23:1075–1084.

77. Obwegeser, HL. Operative Behandlung der zahnlosen progenie ohne intermaxillare fixation. Schweiz Monatschr Zahnhlkd. 1968; 78:416–425.

78. Obwegeser, HL. Die bewegung des unteren alveolarforstatzes zur korrektur von kieferstellungsanomalien: Part 2. Dtsch Z Zeitschrift. 1969; 24:5–15.

79. Obwegeser, HL, Forstchritte und schwerpunkte der orthopadischen kiefer- und gesichtschirurgie. Fortschritte der kiefer-u gesichtschirurgie. Schuchardt, K, Pfeifer, G, eds. Fortschritte der kiefer-u gesichtschirurgie; Vol 21. Thieme, Stuttgart, 1971:54–60.

80. Obwegeser, HL. Mandibular surgery. Br J Oral Surg. 1973; 10:251–253.

81. Obwegeser, HL. Kieferstellungskorrekturen beim erwachsenen spaltpatienten. Dtsch Z Zeitschrift. 1973; 28:688–694.

82. Obwegeser, HL, Grundsatzliches zur korrekturplanung von kiefer- und gesichtsanomalien aus chirurgischer sicht. Fortschr kiefer gesichtschir. Schuchardt, K, Schwenzer, N, eds. Fortschr kiefer gesichtschir; Vol 26. Thieme, Stuttgart, 1981:9–12.

83. Obwegeser, HL, Farmand, M. Unsere behandlung der kiefergelenksankylose. Schweiz Monatschr Zahnhlkd. 1982; 92:569–580.

84. Obwegeser, HL, Maked, MS. Hemimandibular hyperplasia/hemimandibular elongation. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986; 14:183.

85. Obwegeser, HL, Makek, M. Hemimandibulare hyperplasie-hemimandibulare elongation. Zahnnarztl Med Schrifttum, Munchen. 1986; 18:273–313.

86. Obwegeser, HL, Marentette, L. Profile planning based on alterations in the position of the bases of the facial thirds. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986; 44:302–311.

87. Obwegeser, HL, Mekek, M. Hemimandibular hyperplasia-hemimandibular elongation. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986; 14:183–208.

88. Obwegeser, HL. Chirurgische behandlungsmoglichkeiten von sekundardeformierugen bei spaltpatienten. Fortschr Kieferorthop. 1988; 49:272–296.

89. Obwegeser, JA. Eine neue operationsmethode zur osteotomie des gesamten unterkiefer-alveolarfortsatzes. Osterr Z Stomal. 1988; 85:35–46.

90. Obwegeser, HL. Descriptive terminology for jaw anomalies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993; 75:138–140.

91. Obwegeser, HL. Mandibular growth anomalies: Terminology-aetiology-diagnosis-treatment. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2001.

92. Paulus, G, Hirschfelder, U, Festel, H. Computergestutzte quantitative skelettszintigraphie bei der therapieplanung der condylaren hyperplasie. Forstchr Kiefer Gesichtschir. 1987; 32:180–181.

93. Perko, M. Hipertrofija masetera. J Chir Maxillofac Plast. 1963; 4:35–37.

94. Persson, M. Mandibular asymmetry of hereditary origin. Am J Orthod. 1973; 63:1–11.

95. Pogrel, MA. Quantitative assessment of isotope activity in the temporomandibular joint regions as a means of assessing unilateral condylar hypertrophy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985; 60:15–17.

96. Posnick, JC, Asymmetic mandibular prognathism with or without maxillary deformity. Craniofacial and maxillofacial surgery in children and young adults. Posnick, JC, eds. Craniofacial and maxillofacial surgery in children and young adults; Vol 40. WB Saunders Co, Philadelphia, 2000:1057–1080.

97. Posnick, JC, Fantuzzo, J, Orchin, J. Deliberate operative rotation of the maxillo-mandibular complex to alter the A-point to B-point relationship for enhanced facial esthetics. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:1687–1695.

98. Posnick, JC, Fantuzzo, JJ, Troost, T. Simultaneous intranasal procedures to improve chronic obstructive nasal breathing in patients undergoing maxillary (Le Fort I) osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65:2273–2281.

99. Posnick, JC, Agnihotri, N. Managing chronic nasal airway obstruction at the time of orthognathic surgery: A twofer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:695–701.

100. Proffit, WR, Fields, HW, Moray, LJ. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: estimates from the N-HANES III survey. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998; 13:97–106.

101. Raijmakers, PG, Karssemakers, LHE, Tuinzing, DB. Female predominance and effect of gender on unilateral condylar hyperplasia: A review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 70:e72–e76.

102. Reyneke, J, Masireol, C. Condylar hyperplasia: An alternative method of treatment. J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1979; 34:335.

103. Reyneke, JP, Evans, WG. Surgical manipulation of the occlusal plane. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1990; 5:99–110.

104. Robinson, PD, Harris, K, Coghlan, KC, Altman, K. Bone scans and the timing of treatment for condylar hyperplasia. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990; 19:243–246.

105. Rosen, H. Aesthetics in facial skeletal surgery. Perspect Plast Surg. 1993; 6:1.

106. Rubenstein, LK, Campbell, RL. Acquired unilateral condylar hyperplasia and facial asymmetry: Report of case. J Dent Child. 1985; 52:114.

107. Rushton, MA. Growth at the mandibular condyle in relation to some deformities. Br Dent J. 1944; 76:57.

108. Rushton, MA. Unilateral hyperplasia of the mandibular condyle. Proc R Soc Med. 1946; 39:431–438.

109. Rushton, MA. Unilateral hyperplasia of the jaws in the young. Int Dent J. 1951; 2:50.

110. Sarindin, CP, Raijmakers, P, Stootweg, PJ, et al. Unilateral condylar hyperactivity: A histopathologic analysis of 47 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010; 68:47–53.

111. Scholssmann, A. Cited by G Perthes: Operative korrektur der progenie. Zentralbl Chir. 1922; 49:1540–1541.

112. Schultz, LW, Varizani, SJ, Bolden, TE. Unilateral hyperplasia and exostosis of the mandibular condyle: A clinical syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1960; 13:387–395.

113. Severt, TR, Proffit, WR. The prevalence of facial asymmetry in the dentofacial deformities population at the University of North Carolina. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1997; 12:171–176.

114. Simon, GT, Kendrick, RW, Whitlock, RI. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: Case report and its management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977; 43:18.

115. Skaloud, F. New surgical method for correction of prognathism of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1951; 4:689–694.

116. Slootweg, PJ, Muller, H. Condylar hyperplasia. A clinico-pathological analysis of 22 cases. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986; 14:209–214.

117. Smylski, PT. Facial asymmetry and the oral surgeon. J Otolaryngol. 1976; 5:177.

118. Steinhauser, E. Kondylektomie oder korrektive osteotomie bei der kondylaren hyperplasie. Fortschr Kiefer Gesichtschir. 1980; 25:132–135.

119. Steinhauser, EW. Aesthetische und funktionielle korrektur der durch condylare hyperplasie verursachten gesichtsasymmetrie. In: Pfeifer G, ed. Die aesthetik von form und funktion in der plastichen und widerherstellungschirurgie. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 1985:103–109.

120. Tarsitano, JJ, Wooten, JW. The asymmetrical mandible. J Oral Surg. 1970; 28:832.

121. Trauner, R, Obwegeser, H. Zur operationstechnik bei der progenie und anderen unterkieferanomalien. Dtsch Zahn Mund Kieferhlkd. 1955; 23:1–26.

122. Villanueva-Alcojol, L, Monje, F, Gonzales-Garcia, R. Hyperplasia of the mandibular condyle: Clinical, histopathologic, and treatment considerations in a series of 36 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:447–455.

123. Wang-Norderud, R, Ragab, RR. Unilateral condylar hyperplasia and the associated deformity of facial asymmetry. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977; 11:91.

124. Windmaier, W. Die chirurgische behandlung der postoperativen kieferdeformierungen nach lippen-kiefer-gaumenspalten-operationen. Dtsch Zahn Mund Kieferhlkd. 1960; 33:23–35.

125. Wisth, PJ. Mandibular function and dysfunction in patients with mandibular prognathism. Am J Orthod. 1984; 85:193–198.

126. Wunderer, S. Die prognathie-operation mittels frontal gestieltem maxillofragment. Oesterr Z Stomatol. 1962; 59:98–102.