Asthma

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• Describe the role of the following organizations in the management of asthma:

• National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP)

• Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with asthma.

• Describe the epidemiology and risk factors associated with asthma, including the following types of asthma:

• Describe the challenges associated with the diagnosis of asthma, and include the tests used to diagnosis and monitor asthma.

• Differentiate the classifications of asthma severity.

• Describe the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with asthma.

• Describe the general management of asthma.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Introduction

The burdens associated with asthma in the United States—and worldwide—are enormous. Although the precise annual numbers are not known, asthma is clearly linked to a multitude of lost school days, countless missed work days, numerous doctor visits, frequent hospital outpatient visits, and recurrent emergency department visits and hospitalizations. According to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, within the United States in 2005 more than 22 million people were diagnosed with asthma, more than 12 million people had experienced an asthma episode in the previous year, and nearly 4000 Americans died of asthma.* The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about 180,000 people worldwide die because of asthma each year. Clearly, asthma’s impact on health, quality of life, and the economy is substantial.

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program

The first evidence-based asthma guidelines were published in 1991 by NAEPP, under the coordination of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). These guidelines were updated in 1997, 2002, and 2007.† Today the guidelines are structured around the following four components of care: (1) assessment and monitoring of asthma, (2) patient education, (3) control of factors contributing to asthma severity, and (4) the pharmacologic treatments. The NAEPP “stepwise asthma management charts” have been widely used and now specify optimal treatment for specific age groups 0 to 4 years, 5 to 11 years, and 12 years and older.

Global Initiative for Asthma

GINA* was launched in 1993 in collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of NIH and WHO. GINA works with a network of asthma experts and researchers, health-care professionals, professional organizations, and public health-care officials from around the world. GINA gathers and disseminates asthma-related information while also ensuring that a system is in place to incorporate the results of scientific investigations into asthma care. GINA’s specific goals are the following:

• Increase awareness of asthma and it public health consequences

• Promote identification of reasons for the increased prevalence of asthma

• Promote study of the association between asthma and the environment

• Reduce asthma morbidity and mortality

• Improve management of asthma

• Improve availability and accessibility of effective asthma therapy

Collectively, by using the evidence-based guidelines provided by NAEPP, along with the extensive information gathered worldwide from asthma experts and researchers, GINA now provides an outstanding—and user-friendly—evidence-based guideline program for the management of asthma. As of this writing, the GINA programs, which are freely available on the internet (www.ginasthma.org), include the following publications:

• Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (2007). Scientific information and recommendations for asthma programs.

• Pocket Guide for Asthma Management and Prevention (2006). Summary of patient care information for primary health-care professionals.

• Pocket Guide for Asthma Management and Prevention in Children (2006). Summary of patient care information for pediatricians and other health-care professionals.

• What You and Your Family Can Do About Asthma. An information booklet for patients and their families.

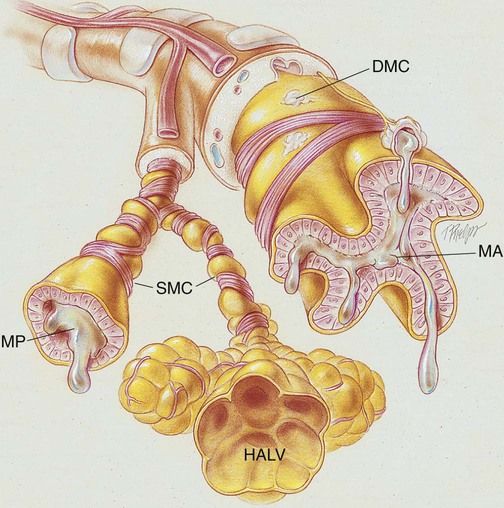

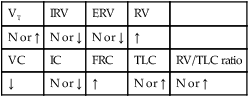

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

Asthma is described as a lung disorder characterized by (1) reversible bronchial airway smooth muscle constriction, (2) airway inflammation, and (3) increased airway responsiveness to an assortment of stimuli. During an asthma attack, the smooth muscles surrounding the small airways constrict. Over time the smooth muscle layers hypertrophy and can increase to three times their normal thickness. The airway mucosa becomes infiltrated with eosinophils and other inflammatory cells, which in turn causes airway inflammation and mucosal edema. The goblet cells proliferate, and the bronchial mucous glands enlarge. The airways become filled with thick, whitish, tenacious mucus. Extensive mucous plugging and atelectasis may develop. The cilia are damaged, and the basement membrane of the mucosa is thicker than normal. As a result of smooth muscle constriction, bronchial mucosal edema, and excessive bronchial secretions, air trapping and alveolar hyperinflation develop. If chronic inflammation develops over time, these anatomic alterations become irreversible, resulting in loss of airway caliber. A remarkable feature of bronchial asthma, however, is that many of the pathologic anatomic alterations of the lungs that occur during an asthmatic attack are completely absent between asthmatic episodes (Figure 12-1).

The major pathologic or structural changes observed during an asthmatic episode are as follows:

Etiology and Epidemiology

Risk Factors

Extrinsic Asthma (Allergic or Atopic Asthma)

Immunologic mechanism

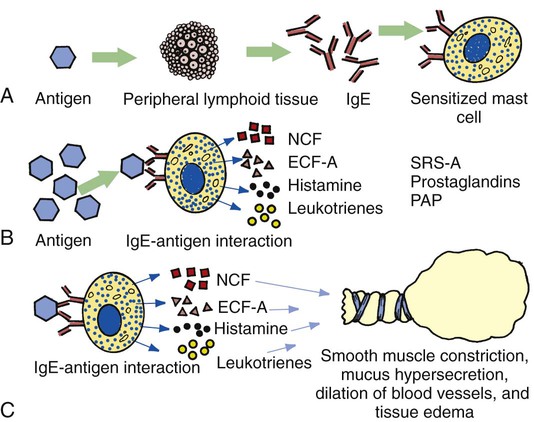

1. When a susceptible individual is exposed to a certain antigen, lymphoid tissue cells form specific IgE (reaginic) antibodies. The IgE antibodies attach themselves to the surface of mast cells in the bronchial walls (Figure 12-2, A).

2. Reexposure or continued exposure to the same antigen creates an antigen-antibody reaction on the surface of the mast cell, which in turn causes the mast cell to degranulate and release chemical mediators such as histamine, eosinophil chemotactic factor of anaphylaxis (ECF-A), neutrophil chemotactic factors (NCFs), leukotrienes (formerly known as slow-reacting substances of anaphylaxis [SRS-A]), prostaglandins, and platelet-activating factor ([PAP]; Figure 12-2, B).

3. The release of these chemical mediators stimulates parasympathetic nerve endings in the bronchial airways, leading to reflex bronchoconstriction and mucous hypersecretion. Moreover, these chemical mediators increase the permeability of capillaries, which results in the dilation of blood vessels and tissue edema (Figure 12-2, C).

Occupational sensitizers (occupational asthma)

Occupational asthma is defined as asthma caused by exposure to an agent encountered in the work environment. More than 300 different substances have been associated with occupational asthma. Occupational asthma is seen predominantly in adults. It is estimated that occupational sensitizers cause about 1 in 10 cases of asthma among adults of working age. High-risk work environments for occupational asthma include farming and agricultural work, painting (including spray painting), cleaning work, and plastic manufacturing. Most occupational asthma is immunologically mediated and has a latency period of months to years after the onset of exposure. Although the cause is not fully understood, it is known that an IgE-mediated allergic reaction and cell-mediated allergic reactions are often involved. Box 12-1 shows additional agents known to cause occupational asthma.

Intrinsic Asthma (Nonallergic or Nonatopic Asthma)

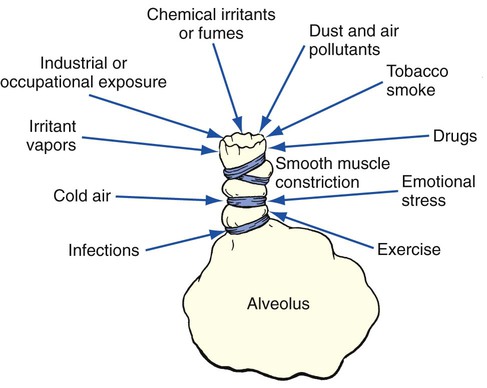

When an asthmatic episode cannot be directly linked to a specific antigen or extrinsic inciting factor, it is referred to as intrinsic asthma (also called nonallergic or nonatopic asthma) (Figure 12-3). The etiologic factors responsible for intrinsic asthma are elusive. Individuals with intrinsic asthma are not hypersensitive or atopic to environmental antigens and have a normal serum IgE level. The onset of intrinsic asthma usually occurs after the age of 40 years, and typically there is no strong family history of allergy.

Diagnosis of Asthma

Furthermore, the diagnosis of asthma is often missed in the patient who acquires asthma in the workplace. This form of asthma is called occupational asthma (see Box 12-1). Because occupational asthma usually has a slow and insidious onset, the patient’s asthma is often misdiagnosed as chronic bronchitis or COPD. As a result, the asthma is either not treated at all or treated inappropriately. Finally, even though asthma can usually be distinguished from COPD, in some patients—those who have chronic respiratory clinical manifestations and fixed airflow limitations—it is often very difficult to differentiate between the two disorders—that is, asthma or COPD.

These symptoms often respond to appropriate antiasthma therapy.

Diagnostic and Monitoring Test for Asthma

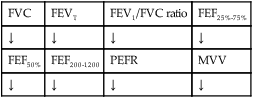

Spirometry measures airflow limitation and its reversibility. An increase in FEV1 of ≥ 12% (or ≥ 200 ml) after administration of a bronchodilator indicates reversible airflow limitation consistent with asthma.

Peak expiratory flow (PEF) measurements are used to diagnose and monitor asthma. An improvement of 60 L/min (or ≥ 20% of the prebronchodilator [PEF] after inhalation of a bronchodilator), or diurnal variation in PEF of more than 20% (with twice-daily readings, more than 10%), suggests a diagnosis of asthma.

Other tests include measurements of airway responsiveness to methacholine, histamine, mannitol, or exercise in order to diagnose. The presence of allergies (including a positive skin test with allergens or measurement of specific IgE in serum) increases the probability of a diagnosis of asthma, and can help identify risk factors that cause asthma symptoms in individual patients.

Classification of Asthma Severity

• Intermittent symptoms are described as those that occur less than once a week and possible brief exacerbations. They may also include nocturnal symptoms not more than twice a month. (Forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] or peak expiratory flow [PEF] ≥ 80% predicted; PEF or FEV1 variability < 20%.)

• Mild persistent symptoms occur more than once a week, but less than once a day and exacerbations may affect activity and sleep. Nocturnal symptoms also occur more than twice a month. (FEV1 or PEF ≥ 80% predicted; PEF or FEV1 variability < 20% to 30%.)

• Moderate persistent symptoms occur daily and exacerbations effect activity and sleep. Nocturnal symptoms occur more than once a week and an individual uses an inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist. (FEV1 or PEF 60% to 80% predicted; PEF or FEV1 variability > 30%.)

• Severe persistent symptoms occur daily along with frequent nocturnal symptoms. There are also limitations on physical activity. (FEV1 or PEF ≤ 60% predicted; PEF or FEV1 variability > 30%.)

• It is important to recognize that asthma severity involves both the severity of the underlying disease and its responsiveness to treatment. For example, asthma can cause severe symptoms and airflow obstruction and be classified as “severe persistent” on initial presentation, but respond fully to treatment and then be classified as “moderate persistent” asthma.

• In addition, severity is not an unvarying feature of an individual patient’s asthma, but may change over months or years.

• Because of these considerations, the classification of asthma severity provided in Table 12-3, which is based on expert opinion rather than evidence, is no longer recommended as the basis for ongoing treatment decisions.

• Its main limitation is its poor value in predicting what treatment will be required and what a patient’s response to that treatment might be.

• For this purpose, a periodic assessment of asthma control is more relevant and useful.

General Management of Asthma

Using the scientific evidence-based information developed by the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP), and the extensive research and input provided by leading asthma experts from around the world, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) now provides an excellent—and user friendly—clinical guideline program for the management and prevention of asthma. The complete GINA documents are available at the following web site: http://www.ginasthma.org. The five major components of asthma care described by GINA are:

Component 1: Develop Patient/Doctor Partnership

Component 2: Identify and Reduce Exposure to Risk Factors

Component 3: Assess, Treat, and Monitor Asthma

Component 3: Assess, Treat, and Monitor Asthma

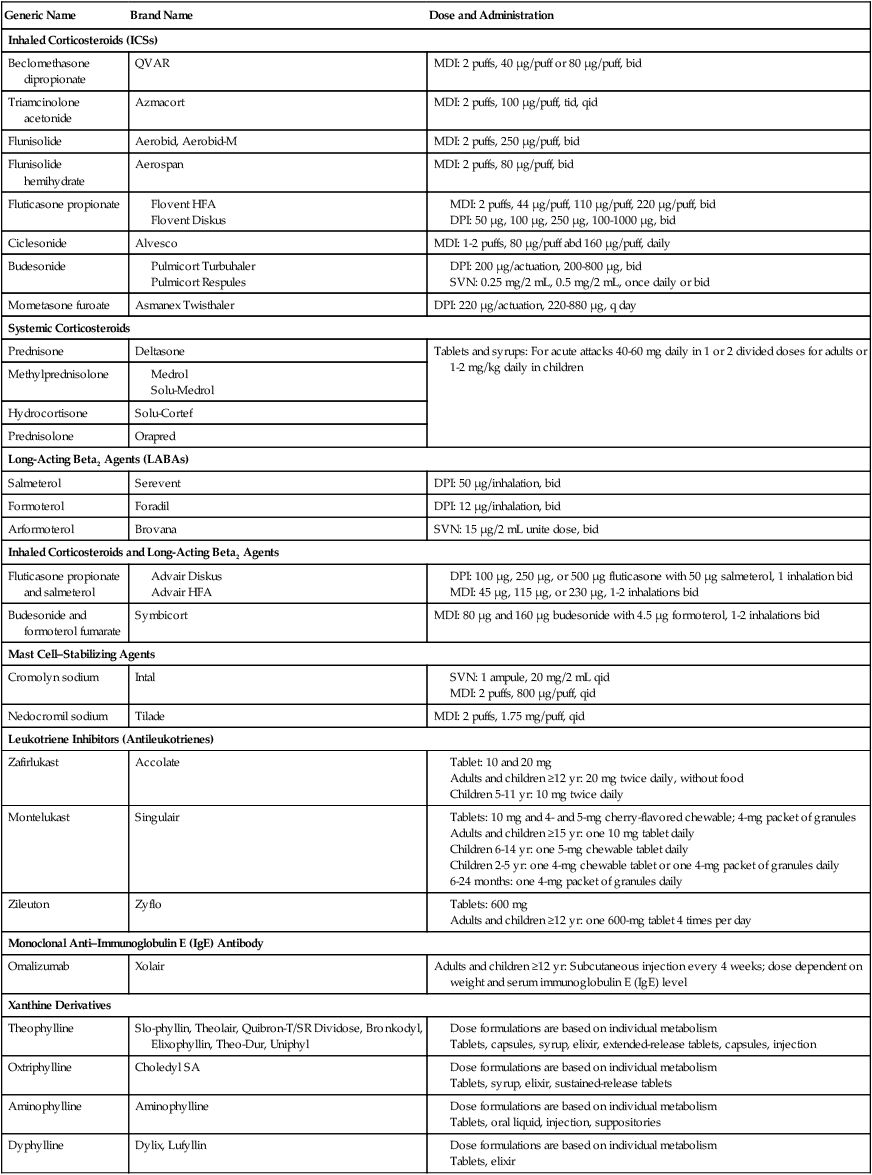

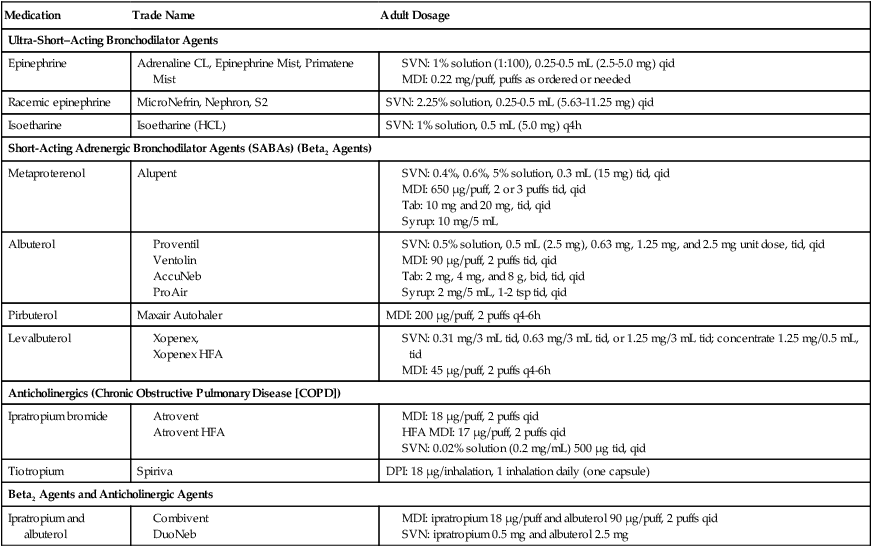

Common controller medications used in the treatment of asthma are presented in Table 12-1. Table 12-2 provides an overview of common reliever medications used to manage acute exacerbations of asthma.

Table 12-1

Controller Medications Commonly Used to Treat Asthma

| Generic Name | Brand Name | Dose and Administration |

| Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICSs) | ||

| Beclomethasone dipropionate | QVAR | MDI: 2 puffs, 40 µg/puff or 80 µg/puff, bid |

| Triamcinolone acetonide | Azmacort | MDI: 2 puffs, 100 µg/puff, tid, qid |

| Flunisolide | Aerobid, Aerobid-M | MDI: 2 puffs, 250 µg/puff, bid |

| Flunisolide hemihydrate | Aerospan | MDI: 2 puffs, 80 µg/puff, bid |

| Fluticasone propionate | ||

DPI, Dry powder inhaler; MDI, metered dose inhaler; SVN, small-volume nebulizer.

Data from Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA): Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, updated 2008. Available at: www.goldcopd.org; and Gardenshire DS: Rau’s repiratory care pharmacology, ed 7, St. Louis, 2008, Elsevier.

Table 12-2

Reliever Medications (Rescue Medications) Commonly Used to Treat Asthma

| Medication | Trade Name | Adult Dosage |

| Ultra-Short–Acting Bronchodilator Agents | ||

| Epinephrine | Adrenaline CL, Epinephrine Mist, Primatene Mist | |

| Racemic epinephrine | MicroNefrin, Nephron, S2 | SVN: 2.25% solution, 0.25-0.5 mL (5.63-11.25 mg) qid |

| Isoetharine | Isoetharine (HCL) | SVN: 1% solution, 0.5 mL (5.0 mg) q4h |

| Short-Acting Adrenergic Bronchodilator Agents (SABAs) (Beta2 Agents) | ||

| Metaproterenol | Alupent | |

| Albuterol | ||

| Pirbuterol | Maxair Autohaler | MDI: 200 µg/puff, 2 puffs q4-6h |

| Levalbuterol | ||

| Anticholinergics (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease [COPD]) | ||

| Ipratropium bromide | ||

| Tiotropium | Spiriva | DPI: 18 µg/inhalation, 1 inhalation daily (one capsule) |

| Beta2 Agents and Anticholinergic Agents | ||

| Ipratropium and albuterol | ||

Data from Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA): Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, updated 2008. Available at: www.goldcopd.org; and Gardenshire DS: Rau’s repiratory care pharmacology, ed 7, St. Louis, 2008, Elsevier.

Component 4: Manage Asthma Exacerbations

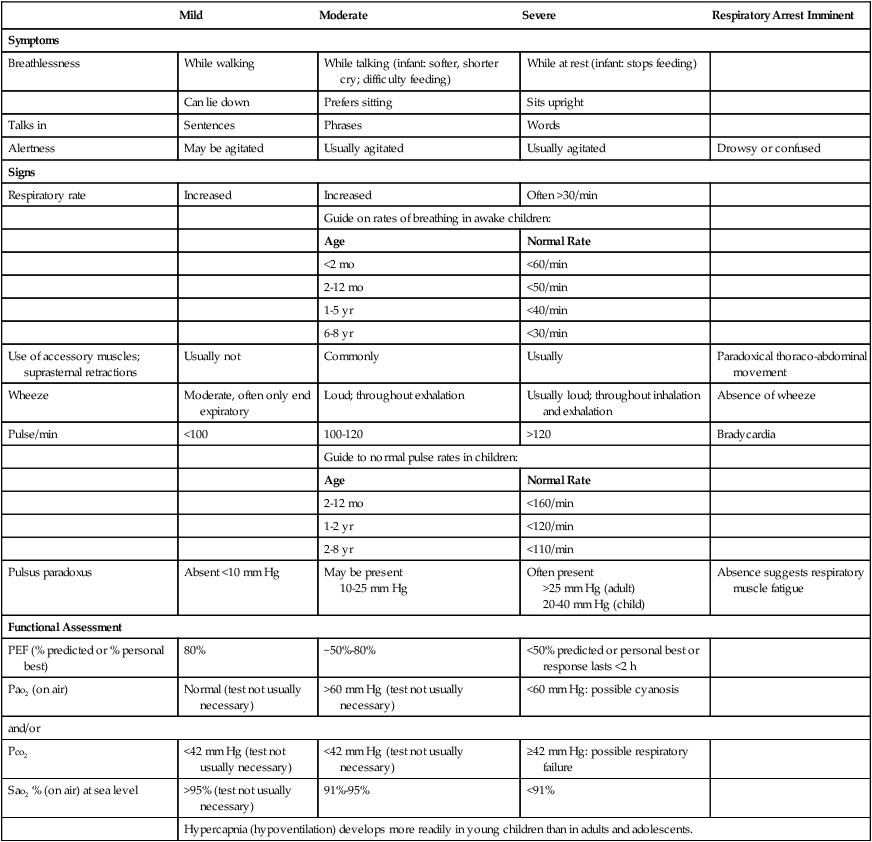

Asthma exacerbation (also called an asthma attack or asthma episode) is defined as a progressive increase in shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, or chest tightness or a combination of these symptoms. A severe asthma exacerbation is life threatening. Table 12-3 provides a clinical scale to classify the severity of asthma exacerbations. The table categorizes the signs, symptoms and assessment into four categories: mild, moderate, severe and respiratory arrest imminent.

Table 12-3

Classification of Severity of Acute Asthma Exacerbations

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Respiratory Arrest Imminent | |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Breathlessness | While walking | While talking (infant: softer, shorter cry; difficulty feeding) | While at rest (infant: stops feeding) | |

| Can lie down | Prefers sitting | Sits upright | ||

| Talks in | Sentences | Phrases | Words | |

| Alertness | May be agitated | Usually agitated | Usually agitated | Drowsy or confused |

| Signs | ||||

| Respiratory rate | Increased | Increased | Often >30/min | |

| Guide on rates of breathing in awake children: | ||||

| Age | Normal Rate | |||

| <2 mo | <60/min | |||

| 2-12 mo | <50/min | |||

| 1-5 yr | <40/min | |||

| 6-8 yr | <30/min | |||

| Use of accessory muscles; suprasternal retractions | Usually not | Commonly | Usually | Paradoxical thoraco-abdominal movement |

| Wheeze | Moderate, often only end expiratory | Loud; throughout exhalation | Usually loud; throughout inhalation and exhalation | Absence of wheeze |

| Pulse/min | <100 | 100-120 | >120 | Bradycardia |

| Guide to normal pulse rates in children: | ||||

| Age | Normal Rate | |||

| 2-12 mo | <160/min | |||

| 1-2 yr | <120/min | |||

| 2-8 yr | <110/min | |||

| Pulsus paradoxus | Absent <10 mm Hg | May be present 10-25 mm Hg |

Often present | |

From National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Expert Panel Report 2: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma, NIH Pub No. 97, July 1997.

Respiratory Care Treatment Protocols

Oxygen Therapy Protocol

Oxygen therapy is used to treat hypoxemia, decrease the work of breathing, and decrease myocardial work. The hypoxemia that develops in asthma is usually caused by the hypoventilation and shuntlike effect associated with bronchospasm and increased airway secretions. Hypoxemia caused by a shuntlike effect can at least partly be corrected by oxygen therapy (see Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-1).

Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol

Because of the excessive mucous production and secretion accumulation associated with asthma, a number of bronchial hygiene treatment modalities may be used to enhance the mobilization of bronchial secretions (see Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-2).

Mechanical Ventilation Protocol

Because acute ventilatory failure is associated with status asthmaticus, continuous mechanical ventilation may be required to maintain an adequate ventilatory status. Status asthmaticus is defined as a severe asthmatic episode that does not respond to conventional pharmacologic therapy. When the patient becomes fatigued, the ventilatory rate decreases. Clinically, the patient demonstrates a progressive decrease in Pao2 and pH and a steady increase in Paco2 (acute ventilatory failure). If this trend is not reversed, mechanical ventilation becomes necessary (see Mechanical Ventilation Protocols, Protocols 9-5, 9-6, and 9-7).

CASE STUDY

Asthma

Admitting History and Physical Examination

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S Patient stated, “It is very hard for me to breathe”

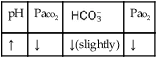

O Vital signs: BP 152/115, HR 220, RR 62, T 100°. Cyanotic and using accessory muscles. Wheezing and rhonchi over both lungs. PEFR: 70 L/min. ABGs pH 7.17, Paco2 71,  22, and Pao2 47. No CXR yet.

22, and Pao2 47. No CXR yet.

• Severe exacerbation of asthma

• Respiratory distress (increased heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate)

• Bronchospasm (wheezing, decreased PEFR, history)

• Excessive airway secretions (rhonchi)

• Acute ventilatory failure (acute respiratory acidosis) with moderate to severe hypoxemia (ABG)

• Metabolic acidosis also likely (both pH and  are both lower than expected for a Paco2 of 71). Likely caused by lactic acid (low Pao2 of 47)

are both lower than expected for a Paco2 of 71). Likely caused by lactic acid (low Pao2 of 47)

P Oxygen Therapy Protocol (Fio2 80%-100% via oxygen nonrebreather mask). Monitor Spo2 with oximeter. Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol (med. neb. every 30 minutes with albuterol 0.15 mL in 2.0 mL normal saline via nebulizer). Monitor PEFR and breath sounds. Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (cough and deep breathe as tolerated). Monitor breath sounds. Place endotracheal tube and mechanical ventilator on standby. Repeat ABG in 30 minutes. Respiratory care practitioner to remain in ED.

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S N/A (patient sedated and paralyzed on ventilator)

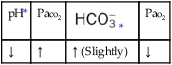

O Sedated, paralyzed, fewer wheezes and rhonchi. Vital signs: BP 122/87, HR 93, T 98.8° F. ABG: pH 7.38, Paco2 37,  23, Pao2 124 (on mechanical ventilator in SIMV mode at a ventilatory rate of 12 and an Fio2 of 0.4)

23, Pao2 124 (on mechanical ventilator in SIMV mode at a ventilatory rate of 12 and an Fio2 of 0.4)

• Less bronchospasm (decreased wheezing, normal ABGs)

• Less bronchial secretions (decreased rhonchi)

• Adequately ventilated and oxygenated on present ventilator settings (ABG)

P Discuss with physician: D/C Norcuron. Continue in-line med. nebs. IMV wean and O2 wean as per Mechanical Ventilation Protocol. Continue to monitor O2 saturation.

Discussion

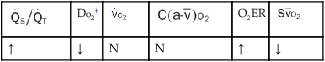

Asthma is a potentially fatal disease—largely because its severity is often unrecognized in the home or outpatient setting. The clinical manifestations presented in this case can all be easily traced back through the Bronchospasm clinical scenario (see Figure 9-11) and Excessive Airway Secretions clinical scenario (see Figure 9-12). For example, the patient’s increased blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate can all be followed back to the hypoxemia caused by the decreased  ratio, pulmonary shunting, and venous admixture activated by bronchospasm and Excessive Bronchial Secretions (see Figure 9-11 and 9-12). The patient’s anxiety and previous use of beta2-agonists also may have contributed to her abnormal vital signs (tachycardia).

ratio, pulmonary shunting, and venous admixture activated by bronchospasm and Excessive Bronchial Secretions (see Figure 9-11 and 9-12). The patient’s anxiety and previous use of beta2-agonists also may have contributed to her abnormal vital signs (tachycardia).

In addition, the decreased PEFR, use of accessory muscles, diminished breath sounds, rhonchi, and wheezing reflect the increased airway resistance and air trapping caused by the Bronchospasm (see Figure 9-11) and Excessive Airway Secretions (see Figure 9-12). The fact that the patient’s arterial blood gas values showed acute ventilatory failure confirmed that the patient was in the severe stages of an asthmatic episode and that mechanical ventilation was justified, although vigorous routine respiratory care was first tried to prevent this.

After the initial assessment, the respiratory care practitioner chose a fairly aggressive approach to both the Oxygen Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-1) and the Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-4). Use of a nonrebreather oxygen therapy mask at initially high Fio2 levels (0.8 to 1.0) allowed him to adjust the Fio2 in small, precise concentration changes while not risking rebreathing of expired air. Frequent monitoring of ABGs and Spo2 levels was appropriate. Note also the frequency with which he chose to administer inhaled bronchodilators (every 30 minutes) in the Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol. An alternative approach, often used in pediatric patients, would be to use continuous bronchodilator or aerosol therapy.

*www.cdc.gov/asthma/aag07.htm.

†Expert Panel Response 3 (EPR 3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma, 2007. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm.

*Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA): Global strategy for asthma management and prevention, updated 2007. The GINA reports are available at www.ginasthma.org.

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

22, and Pa

22, and Pa 23, and Pa

23, and Pa