Assessment of the Patient With a Cardiac Arrhythmia

History Taking

Symptoms and Signs

Skipped Beats Versus Sustained Palpitation

In this fashion, the clinician can obtain information about the nature of the beginning and end of the tachycardia, whether the ventricular rhythm is regular or irregular, and the rate of the tachycardia. Knowledge about the typical onset and termination of the tachycardia is helpful. Abrupt, paroxysmal onset is consistent with a tachycardia such as AV nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT; see Chapter 77), whereas gradual speeding and slowing are more in keeping with a sinus tachycardia (see Chapter 72). Termination by Valsalva maneuver or carotid sinus massage suggests a tachycardia incorporating nodal tissue in the reentrant pathway, such as sinus node reentry, AVNRT, or AV reentrant tachycardia (AVRT; see Chapters 77 and 76), and idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia. It often is helpful to have the patient tap out the cadence of the perceived palpitations, from onset to termination.

The rate of the untreated tachycardia often narrows diagnostic possibilities, and patients should be taught to count their radial or carotid pulse rate. Ventricular rates of 150 beats/minute (bpm) should always suggest the potential diagnosis of atrial flutter with 2 : 1 AV block (see Chapter 74), whereas most supraventricular tachycardias, such as those caused by AVNRT or AVRT, usually occur at rates exceeding 150 bpm. The rates of VTs overlap those of the supraventricular tachycardias. Palpitations, hot flashes, and sweating in middle-aged women suggest perimenopausal syndrome. Palpitations, dizziness, and shortness of breath on mild exertion, typically in young women with structurally normal hearts, suggest the syndrome of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Palpitations owing to sinus tachycardia on standing should point toward postural hypotension. Palpitations and presyncope on standing can be symptoms of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Various possible causes of palpitations are listed in Box 58-1.

Presyncope and Syncope

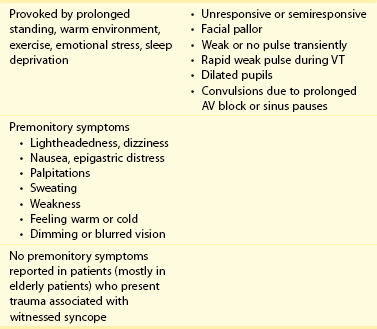

The diagnosis of presyncope and syncope and its cause requires comprehensive history taking from the patient and witness. The differential diagnosis of syncope is lengthy and can be a warning sign of SCD (Chapter 99, Table 99-1). It is important to differentiate cardiac versus noncardiac causes of syncope. It is more important to differentiate a benign cause of syncope from a malignant cause. Of the reflex syncopes (neurocardiogenic, carotid hypersensitivity, and situational), neurocardiogenic is the most common. It should be differentiated from syncope owing to orthostasis, which is commonly seen in autonomic failure (e.g., due to diabetes), and from syncope resulting from other cardiac causes.

Laboratory Tests

Short-Term and Long-Term Continuous Ambulatory Electrocardiographic Monitoring

1. 24- to 48-hour ambulatory Holter monitoring. Short-term continuous Holter monitoring may be sufficient for patients with daily symptoms related to arrhythmia such as palpitation, presyncope, or syncope. If the arrhythmia does not occur with sufficient frequency, then a simple 24-hour, or even 48-hour, recording will not be useful. Newer Holter monitors also record a 12-channel ECG. Such studies are helpful in arrhythmia characterization including atrial fibrillation, as well as ST-T wave changes related to ischemia and Brugada syndrome.

2. Long-term (15-day) Holter monitoring system. These systems are used for diagnosing arrhythmias occurring once or twice in a week. With these devices, cardiac activity is continuously recorded by chest electrodes that are attached to a pager-sized sensor. The sensor of the pager wirelessly transmits collected data to a portable monitor that analyzes the rhythm data. If an arrhythmia is detected by an arrhythmia algorithm, the monitor automatically transmits recorded data wirelessly via the internet to a central monitoring station for subsequent analysis. Patient activated data is also transmitted.

3. Event recorders (with and without loop):

a. Trans-telephonic monitoring (TTM) systems are external event recorders without loop; they are noncontinuous ambulatory recording system.1 After activation by the patient, an ECG is recorded and directly transmitted by telephone to a receiving center.

b. Event recorders with looping memory (continuous event recorders [CERs]) make a continuous one-lead recording, but the rhythm strip will only be saved when a patient activates the device. Most devices can be programmed to save preactivation and postactivation rhythm strips.

c. Autotriggered event monitors with looping memory (autotriggered CER) devices automatically recognize prespecified high and low heart rates. One such device performs a continuous ECG analysis combined with automatic storage of abnormal events detected in a 20-minute solid-state memory with continuous loop analysis up to 7 days. In addition, it also records patient-trigger events. The most recent advancement in ambulatory arrhythmia monitoring is mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry in which a portable sensor continuously detects asymptomatic, prespecified arrhythmias and transmits the ECG data in real-time to a pocket-sized monitor at the patient’s home. If the algorithms in the monitor detect an abnormal heartbeat, the monitor automatically transmits the patient’s ECG data to the monitoring center using wireless communications.

4. Implantable autotriggered and patient-triggered loop recorders. An implantable loop recorder placed beneath the skin can be used for monitoring of the cardiac rhythm for as long as 12 to 24 months. Therefore, it is useful in patients with infrequent symptoms. The device has both autotriggered and patient-activated arrhythmia recording facilities. The devices are also available for recording a specific arrhythmia, such as atrial fibrillation. Use of such devices has been successful in recording tachyarrhythmias and, more commonly, bradyarrhythmias. Arrhythmia recordings can be sent to the analyzing center via the telephone and then to physicians via the Internet.

5. Pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Dual-chamber pacemakers can record atrial and ventricular high-rate episodes and can be correlated with the arrhythmia. Apart from diagnosing ventricular arrhythmia, a dual-chamber implantable cardioverter defibrillator also helps in identifying cycle length, duration, and frequency of atrial arrhythmias.

Correlation With Cardiac Arrhythmias on 24-Hour and Long-Term Electrocardiographic Monitoring

Twenty-Four–Hour Holter Recordings

In a study of 518 patients, 24-hour Holter recordings were performed for palpitations and other symptoms related to arrhythmia. Two hundred seventy-four (53 %) had significant arrhythmias (41% ventricular and 20% ventricular, 8% both).2 No presenting complaint or cardiovascular diagnosis correlated closely with any specific cardiac arrhythmia. Major arrhythmias, including supraventricular and ventricular tachycardias, often occurred asymptomatically (in 44 of 54 and 37 of 40 patients, respectively). Among 371 patients with accurate historic logs, only 176 (47%) who had long-term electrocardiographic monitoring had typical symptoms during the monitoring period. Only 50 patients (13%) had concurrence of their presenting complaints with an arrhythmia, whereas 126 patients (34%) had their typical symptoms associated with a normal electrocardiogram, which may be helpful in excluding any cardiac arrhythmia as the primary cause for their complaints.

Continuous Event Recording Versus 24- to 48-hour Holter Monitoring

Studies have shown that with CER, a diagnosis can be established in 21% to 62% of the patients, compared with a maximum of 30% with Holter monitoring. The CER is also better than the Holter monitor at excluding arrhythmias during symptoms (34% and 2%, respectively).1

Autotriggered Continuous Event Recording Versus Traditional Continuous Event Recording Versus Holter recording

In a larger study of 1800 patients, the autotriggered CER was compared with the traditional CER and 24-hour Holter monitoring with 600 patients in each group. The diagnostic yields were 71%, 27%, and 6% in autotriggered-CER, patient-triggered CER, and 24-hour Holter monitoring groups, respectively.3

ILR Versus Noninvasive Testing

Giada et al.4 studied 50 patients for the diagnostic yield of the use of insertable loop recorder (ILR), which was randomly compared with conventional strategy (24-hour Holter recording, a 4-week period of CER, or electrophysiological testing if the previous two strategies yielded negative results).4 The diagnosis was made in only five patients (21%) of 25 patients in the conventional strategy group compared with 19 (73%) of 25 patients in ILR group (with arrhythmia recording up to 1 year).

Stress Testing and Other Noninvasive Studies

An exercise stress test can be useful, particularly in patients who experience symptoms when exercising (see Chapter 63). In response to exercise testing, approximately one third of normal subjects have ventricular ectopy, usually in the form of occasional uniform PVCs. These PVCs are more likely to occur at greater heart rates and are not reproducible from one test to the next. Multiform PVCs, pairs of PVCs, and VT infrequently develop in response to exercise in healthy subjects. Because they can be recorded in normal subjects, their presence does not establish the existence of ischemia or heart disease. Ventricular ectopy generally appears at lower heart rates (<130 bpm) in patients with coronary artery disease than in a normal population, and it often occurs in the early recovery period. Ventricular arrhythmias are more reproducible from one test to the next in patients with coronary artery disease, and more frequent PVCs (exceeding 10 per minute), polymorphic PVCs, and VT are more likely to occur in patients with coronary artery disease than in persons with normal hearts. PVCs at rest can be suppressed by exercise in patients with documented coronary disease; therefore, this observation does not necessarily imply a benign prognosis or absence of underlying structural heart disease. In normal subjects, results from consecutive exercise tests might not be reproducible, whereas the test results are more reproducible in patients with coronary artery disease, but not dependably so. Exercise testing may be useful to expose ECG abnormalities in patients with less obvious forms of the long QT syndrome.

A variety of noninvasive tests have been developed in an attempt to identify patients at risk for sudden arrhythmic death. These tests include signal-averaged electrocardiography, heart rate variability QT dispersion testing, T wave alternans assessment, and baroreflex testing. Although these tests can help to identify groups of patients at greater or lower risk for SCD, they all suffer from an inability to predict precisely the occurrence of life-threatening arrhythmias in individual patients (see Chapters 65 to 69).

Tests Indicated for Specific Symptoms

Tachyarrhythmias

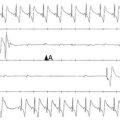

As mentioned earlier, a 12-lead ECG should be obtained during tachycardia, as long as the patient’s condition is relatively stable. If the QRS is normal and identical to that present during sinus rhythm, the tachycardia must be supraventricular, and the differential diagnosis now relates to its mechanism (see Chapters 73 77–79). The 12-lead ECG provides many diagnostic clues in this regard. Supraventricular tachycardias can be classified as short RP′ or long RP′ tachycardias, depending on the timing of the P wave in relation to the preceding R wave. When a P wave occurs closer to the preceding R wave (i.e., in the first half of the R-R interval), the tachycardia is called a short RP′ tachycardia, whereas if a P wave occurs in the second half of the RR cycle, the arrhythmia is called a long RP′ tachycardia. Considerations in the differential diagnosis for a short RP′ tachycardia include AVNRT, AVRT, junctional tachycardia, and atrial tachycardia with a markedly prolonged PR interval. If no P waves or other evidence of atrial activity are apparent, and the R-R interval is regular, AVNRT is most likely. If a retrograde P wave is present in the ST segment, AVRT is most probable. Long RP tachycardias include sinus tachycardia, atypical AVNRT, permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia, and atrial tachycardia. The presence of conduction over an accessory pathway during sinus rhythm or during tachycardia naturally suggests that the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome with its associated accessory pathway is responsible for the dysrhythmia. During VT, specific QRS contours and the presence of AV dissociation are useful in making the diagnosis.

References

1. Hoefman, E, Bindels, PJ, van Weert, HC. Efficacy of diagnostic tools for detecting cardiac arrhythmias: systematic literature search. Neth Heart J. 2010; 18(11):543–551.

2. Zeldis, SM, et al. Cardiovascular complaints. Correlation with cardiac arrhythmias on 24-hour electrocardiographic monitoring. Chest. 1980; 78(3):456–461.

3. Reiffel, JA, Schwarzberg, R, Murry, M. Comparison of autotriggered memory loop recorders versus standard loop recorders versus 24-hour Holter monitors for arrhythmia detection. Am J Cardiol. 2005; 95(9):1055–1059.

4. Giada, F, et al. Recurrent unexplained palpitations (RUP) study comparison of implantable loop recorder versus conventional diagnostic strategy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 49(19):1951–1956.