Assessment of Perioperative Events and Problems

Ricardo Martinez-Ruiz and Christopher J. Gallagher

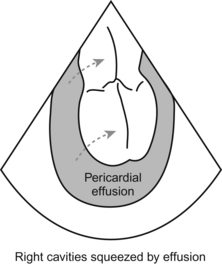

Hypotension and Causes of Cardiovascular Instability

The TEE is the anticrash weapon of choice.

The TEE gives you the real picture, right now, no need for a leap of faith.

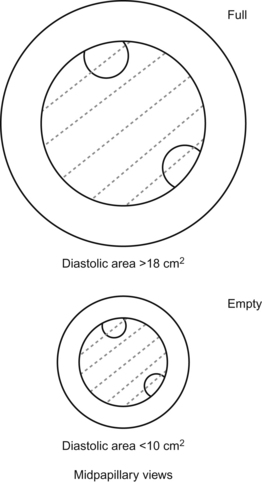

1. End-diastolic area decreased, ventricle contracting OK—You’re low on volume. The heart is empty, so fill it.

2. End-diastolic area increased, ventricle contracting poorly—You have a bad and already overfilled ventricle. Fix whatever’s causing the global hypokinesis (Get a blood gas! Don’t forget the basic stuff!), and once you’ve fixed what you can fix, it’s time for inotropes or ventricular support of some kind.

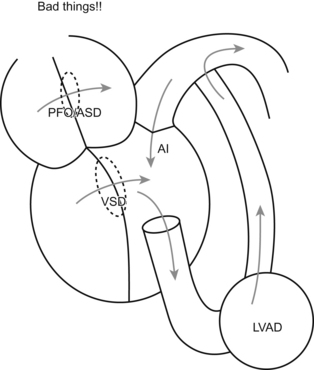

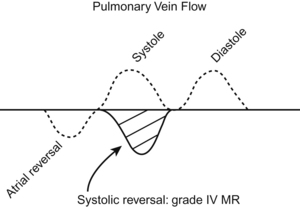

3. End-diastolic volume normal or low, ventricle contracting well or hyperdynamic—You have a problem with the volume not “going where it’s supposed to go”. Either the volume is all going out into a vastly dilated circulatory tree (anaphylaxis with low systemic vascular resistance), or else some other channel is misrouting your good cardiac output (severe mitral regurg or aortic regurg, or a ventricular septal defect).

Cardiac Surgery: Techniques and Problems

Assessment of Bypass and Cardioplegia

Cannulas and Devices Commonly Used During Cardiac Surgery

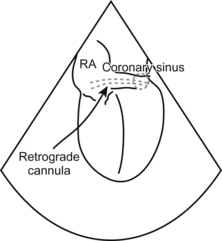

To see the coronary sinus on TEE, you need to get your ME 4-chamber view and slowly advance the probe into the stomach and VOILA!!! The coronary sinus shows up as a drak conduit that drains into the right atrium (you can check with Doppler to see the coronary sinus blood flow). Ocassionally you may have a valve (Thebesian valve) impeding the easy positioning of the retrograde cannula, the cannula gets stuck on it. It is pretty cool to tell your surgeon that the reason he is struggling getting it in position is because of the valve.

What else might Show up During Cardiac Surgery?

The tip of your dual stage cannula should be just into the IVC.

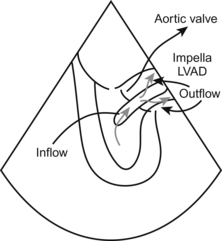

Circulatory Assist Devices

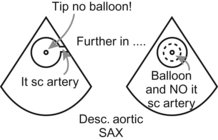

It’s not a stretch to look for correct placement of an intra-aortic balloon pump. You want to see the tip of the IABP at the takeoff to the left subclavian artery. No higher (occlusion to the left arm) and no lower (inadequate function of the balloon pump and potential occlusion of renal arteries, oops). You should see the tip of the IABP, but no balloon!, at the level of the takeoff of the Lt subclavian artery on the most upper view of the descending thoracic aorta. As soon as you push the probe deeper, the balloon should be visible with its characteristic up and down, up and down… (you can also assess the quality of expansion of the balloon).

Things can get more exotic, of course.

Once the LVAD is going, you can also use the TEE to confirm that the aortic valve isn’t opening. At first that concept seems a little jarring.

Minimally Invasive Cardiopulmonary Bypass

(Perhaps more accurately called “Minimally done anymore cardiopulmonary bypass”.)

Off-pump Cardiac Surgery

No can do the transgastric view, no way.

Hike the heart, the view goes away.

What tells you things are going to the dogs?

Low blood pressure unresponsive to your usual blandishments.

Low blood pressure unresponsive to your usual blandishments.

Ectopy so bad that you get ectopy.

Ectopy so bad that you get ectopy.

Increasing mitral or tricuspid regurgitation.

Increasing mitral or tricuspid regurgitation.

Regional wall motion abnormalities that persist and persist and (when the hell are they going to finish the graft!?) finally make you and everybody panic and say, “BASTA! The patient’s dying! Stop!”.

Regional wall motion abnormalities that persist and persist and (when the hell are they going to finish the graft!?) finally make you and everybody panic and say, “BASTA! The patient’s dying! Stop!”.

So how much and how long of a wall motion abnormality is enough to push you “onto the pump”?

2. They clamp the vessels to sew in the graft.

3. Things get bad, you limp along with volume, a little Neo maybe, you hope things don’t get too bad.

4. TEE confirms that you are limping along, but you hope things get better.

5. Things either get better or they don’t.

6. If they don’t, if the wall motion abnormality does NOT go away, then you have to reexamine that graft and make sure it’s working OK. (If you had an on-pump case and had a new regional wall motion abnormality, you would reinvestigate your graft, wouldn’t you?)

Coronary Surgery: Techniques and Assessment

How will TEE help you in an on-pump CABG? (Since we talked about off-pump just a second ago.)

TEE also helps in regional wall motion abnormality analysis. This goes right back to another previous discussion in Chapter 14 (see Coronary Artery Distribution and Flow).

This comes in especially handy once the chest is closed. The skin and sternum are “in the way” and the TEE helps you see what your eyes no longer can.

Valve Surgery: Techniques and Assessment

Valve Replacement: Mechanical, Bioprosthetic, and Other

TEE helps you keep the blood going round in circles in your patient, and Oh be Joyful to that. How?

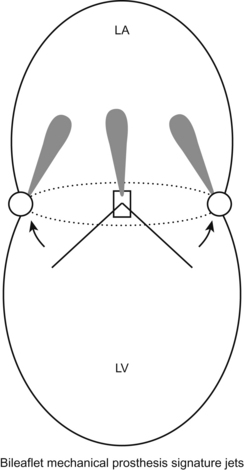

St. Jude and Carbomedics

(Always these double names! At least they settled on just one saint for the St. Jude.)

Bi-leaflet, metallic >>> easy to see leaflet movement. These leaflets can get stuck (by clot or tissue) and will produce severe MR.

Great durability, need anticoagulation.

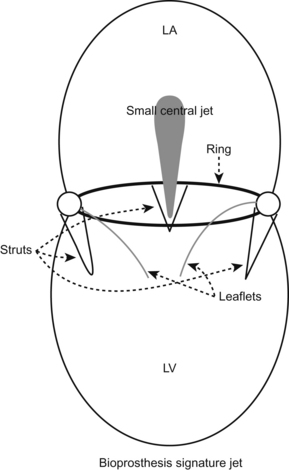

They have signature regurgitant jet pattern to reduce clot formation.

Ross Procedure

There are stentless prosthetic valves. You won’t see the metal and their reflections, but you may see a sewing ring. That is an extremely subtle finding and easy to miss.

An issue with tissue valves is longevity. They tend to wear out faster.

Valve Repair

Mitral Repair?

After the repair is done, you will look at the mitral valve again, making sure, well, that the repair worked! Regurg gone (good), but not so gone that you have moved all the way to mitral stenosis (not good).

Transplantation Surgery

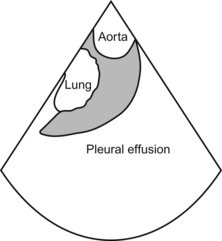

Lung

Most lungs are, you sincerely hope, full of air, so it’s a toughie to examine them with TEE. Unless the lung is consolidated you might be able to “see” the parenchyma > bad thing. Also with big pleural effusions you can see the lung “floating” in the descending thoracic aortic views. You can also see the presence of clot and fibrin in the fluid (pretty cool).

What more can I say—by now we keep coming back to the main things a TEE does!

Questions

1. When placing an LVAD you should look for, except:

2. The inflow cannula for the Tandem Heart is located in:

3. The mitral regurgitant jet of a bioprosthesis is, except:

4. In the case of an anaphylactic shock the heart is/has:

5. In order to assess for contractility in an off pump CABG, you should, except: