Chapter 29

Assessment of Nutritional Status1

One must eat to live, and not live to eat.

Jean Baptiste Molière (1622–1673)

Nutrition is one of the most important factors involved in an individual’s health and disease because it affects almost every system. It has been shown that dietary habits contribute importantly to the pathogenesis of many of the major causes of death in the United States.

One of the most challenging nutritional problems in the world today is obesity. In 2008, more than 1.4 billion adults, 20 and older, were overweight. Of these, more than 200 million men and nearly 300 million women were obese. In the United States, the prevalence of obesity doubled among adults between 1980 and 2004, affecting more than 68% of adults and 33% of children and adolescents. Minority populations are particularly at risk, with 76% of African-American adults and 80% of Mexican-American adults either overweight or obese. Obesity is a risk factor for many diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, cancers of the breast and endometrium, and hepatobiliary disease. There is an increased awareness of obesity, but it remains a major problem. The overall cost to society of obesity is estimated to be more than $100 billion per year.

Malnutrition is also a problem in the United States. Surveys have shown that among general medical and surgical admissions to hospitals, approximately 50% of the patients suffer from some form of malnutrition. Approximately 25% may actually have functional disease related to it, and 10% may have evidence of advanced malnutrition. Malnutrition is a problem that targets a number of specific populations, including older persons who live alone, chronically ill patients, adolescents who eat and diet erratically, and patients with recently diagnosed cancer in whom chemotherapeutic and radiation therapeutic protocols may promote nutritional problems. Even obese patients may suffer from malnutrition, most commonly secondary to catabolic stress.

Health care providers have a unique opportunity to educate patients and help modify their behavior. More than half of these health-promoting behaviors are nutrition related. They include balancing caloric intake to match energy expenditure, limiting salt consumption, reducing cholesterol intake, taking vitamins, and decreasing dietary saturated fat consumption. The health care professional must have a firm understanding of clinical nutrition and its influence on health and illness. A patient’s ability to recover from an illness or from surgery depends, in many cases, on his or her past and current nutritional status. Adequate protein-calorie nutrition is important for wound healing, recovery from infection, and responsiveness to treatment, and protein-calorie malnutrition may be a factor in development of decubitus ulcers and wound disruption. Five of the leading causes of death in this country—heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis—are diet-related. Therefore, knowing what patients eat, the nutritional adequacy of their diets, and their clinical nutritional status is a necessary component of physical diagnosis.

This chapter focuses on the aspects of the history and physical examination that constitute a nutritional assessment. At present, there is no standardized set of dietary history questions or method for assessing nutritional status. Rather, nutritional assessment requires the integration of information obtained from the medical history and physical examination. Throughout this chapter, nutritionally focused questions and examples of diet-related diseases are provided to assist in building history-taking and physical examination skills. The chapter begins with a review of the medical history and physical examination, demonstrating the integration of nutritionally focused information. Then it covers the nutritional assessment of select patient groups, followed by some pathophysiologic correlations.

Medical History

Chief Complaint

Often the chief complaint is directly related to the patient’s nutrition, which may affect treatment and prognosis. The most commonly voiced nutritional concerns are “loss of appetite,” “weight loss,” “weight gain,” and “weakness.” Changes in dietary intake and in weight are among the earliest signs of medical problems. These complaints should prompt a detailed inquiry about diet and related symptoms in the history of present illness.

History of Present Illness

After asking the patient to describe the symptoms or medical problem that caused him or her to seek medical attention, begin to explore any diet-disease relationship that may exist. The following self-directed questions should guide your inquiry:

Body Weight History

Body weight is a global indicator for overall health. Any weight loss is a good general indication of the severity or systemic nature of the presenting symptoms, whether they are acute or chronic. Both low body weight and unintentional weight loss have been shown to be predictive of increased morbidity and mortality. Although the cause of weight loss is often linked to the presenting medical problem, often no identifiable physical cause is apparent. In all cases, the underlying reasons for the weight change should be explored and the amount of weight loss clearly defined. Information-yielding questions include the following:

“How much weight did you lose or gain?”

“What was your weight before the symptoms started?”

“During what period did you experience the weight loss or gain?”

“How was your appetite over this time?”

“Do you know what may have contributed to your change in weight?”

Rapid weight gain is often an indicator of fluid retention and may be accompanied by edema or ascites. Common diseases associated with rapid weight gain include congestive heart failure, liver disease, and renal disease. In contrast, rapid weight loss usually signifies loss of body tissue, unless the patient has been undergoing therapeutic diuresis (in which case the patient would report markedly increased urination) or is experiencing dehydration (in which case the patient would report decreased fluid ingestion, dry mouth, weakness, and dizziness). If the patient has experienced weight loss, it is useful to think in terms of the percentage of weight lost over a specific time frame. To convert absolute pounds into percentage lost, the following simple equation is used:

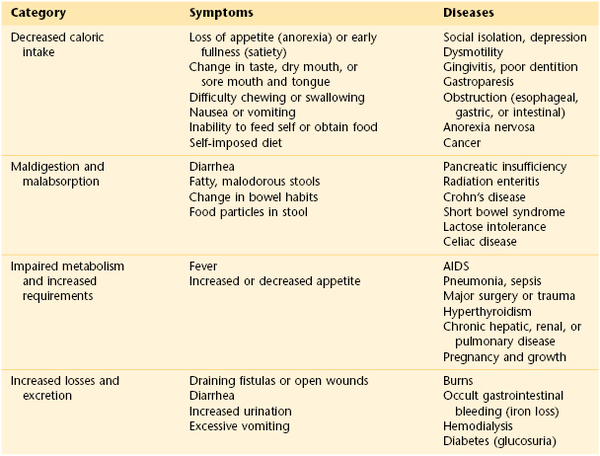

Significant involuntary weight loss is generally defined as more than 5% of usual weight during the preceding 6 months or 10% or more within the year. When a patient has experienced weight loss, it is useful to direct your questions toward the underlying causes. There are four physiologic categories for weight loss: (1) decreased caloric intake, (2) malabsorption or maldigestion, (3) impaired metabolism or increased requirements, and (4) increased losses or excretion (Table 29-1).

Past Medical History

As patients list their past illnesses, the health care provider should consider the role of nutrition or diet in the cause or treatment. Common diet-related diseases include cardiovascular disease (coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease), hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, some forms of cancer, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and other gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. In addition to asking how the illness was diagnosed and what treatment was rendered, ask the patient whether he or she received dietary counseling or altered his or her diet in response to the diagnosis. Try to ascertain the patient’s understanding of the role that diet plays in the condition.

Past Surgical History

All surgical procedures should be recorded in this section, along with serious surgical complications such as draining fistulas, abscesses, open wounds, and chronic blood loss. These complications often lead to malnutrition and the need for specialized nutritional support, including enteral and parenteral feedings. If the patient is currently in the postoperative period, you should consider the role of nutritional support in the recovery process and how the particular surgery has altered the patient’s dietary habits and requirements. For example, a patient with a total gastrectomy needs to alter his or her diet to reduce simple sugars, eat multiple small meals each day, and receive supplemental vitamin B12 and iron to maintain good nutritional health.

Medications

The medication history should include both prescription and over-the-counter medications. Because complementary and alternative therapies have become popular, many patients take vitamins, minerals, herbs (Table 29-2), and other dietary supplements that they may not mention without prompting. A thorough review of alternative therapy use should be a standard part of the patient medication and lifestyle history. When eliciting this information, be careful not to be judgmental or accusatory. Many patients do not disclose this information because of fear of being censured. Suggested questions are as follows:

“What is the reason you are taking the supplement?”

“Have you experienced any side effects or benefits from the supplements?”

“Is anybody monitoring you, such as your doctor, nutritionist, or herbalist?”

“What is your consumption of grapefruit and grapefruit juice?”

Table 29–2

Commonly Used Herbs and Their Side Effects

| Herb | Common Use | Side Effect and Interaction |

| Echinacea | Treatment and prevention of upper respiratory infections, common cold | Rash, pruritus, dizziness |

| St. John’s wort | Treatment of mild to moderate depression | Gastrointestinal upset, photosensitivity |

| Gingko biloba | Treatment of dementia | Mild gastrointestinal distress, headache; may have anticoagulant effects |

| Garlic | Treatment of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, atherosclerosis | Gastrointestinal upset, gas, reflux, nausea, allergic reaction, antiplatelet effects |

| Saw palmetto | Treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia | Uncommon |

| Ginseng | General health promotion, energy | High doses: diarrhea, hypertension, insomnia, nervousness |

| Goldenseal | Treatment of upper respiratory infections, common cold | Diarrhea, hypertension, vasoconstriction |

| Aloe | Topical application for dermatitis, herpes | Possible delay in wound healing after topical application; diarrhea and hypokalemia with oral use |

| Siberian ginseng | Similar to those of ginseng | May alter digoxin levels |

| Valerian | Treatment of insomnia, anxiety | Fatigue, tremor, headache, paradoxical insomnia |

Drugs and nutrients interact in many ways to affect both nutritional status and the effectiveness of drug therapy. Drugs may influence nutritional status by several physiologic mechanisms: altering food intake (through changes in appetite, nausea, altered taste sensations), producing malabsorption (through alterations in intestinal mucus, motility, or pH; competition with nutrients for absorption sites; binding of bile acids), or modifying excretion (through renal tubular reabsorption or secretion). Drug-induced nutrient deficiencies usually develop slowly and are more likely in patients who use drugs chronically, especially older adults. Other risk factors include high drug dosages, multiple drug dosages, multiple drug regimens, poor diets, and marginal nutrient stores. Table 29-3 lists examples of drug interactions and nutrient metabolism.

Table 29–3

Drug Interactions and Nutrient Metabolism

| Drug Class and Examples | Nutrients Affected |

| Antacids | |

| Aluminum hydroxide | Phosphorus |

| Magnesium trisilicate | Iron |

| Antibiotics | |

| Tetracyclines | Calcium, magnesium, iron, vitamin B12 |

| Neomycin, kanamycin | Fat-soluble vitamins, vitamin B12 |

| Sulfasalazine | Folate |

| Anticonvulsants | |

| Phenobarbital, phenytoin | Calcium, vitamin D, folate |

| Hypolipidemics | |

| Cholestyramine, colestipol | Fat and fat-soluble vitamins |

| Cytotoxic agents | |

| Methotrexate | Folate |

| Laxatives | |

| Mineral oil | Water, electrolytes, fat, and fat-soluble vitamins |

| Antituberculotics | |

| Isoniazid | Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) |

| Anticoagulants | |

| Warfarin | Vitamin K |

| Analgesics | |

| Aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Iron |

| Diuretics | |

| Thiazides, furosemide | Potassium, magnesium, calcium, zinc |

| Antineoplastic agents | |

| Cisplatin | Potassium, magnesium |

Studies by Bailey and associates (1998) revealed possible drug interactions involving grapefruit and grapefruit juice (fresh or frozen) with several common medications used to treat high blood pressure, anxiety, depression, cancer, gastroesophageal reflux disease, erectile dysfunction, angina, convulsions, and human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome. In general, the grapefruit or its juice tends to increase the drug’s effect. The advisory also cautioned that sour oranges and tangelos may also interfere with medication blood levels. Other citrus fruits were considered safe. The study stated that as little as one 8-oz (0.26-mg) glass of grapefruit juice could increase the blood drug level and the effects could last for 3 days or more.

Allergies and Food Intolerances

In addition to asking about allergies to medications and environmental allergens, the interviewer should inquire about allergies and intolerances to food. The most common allergenic foods among adults are peanuts, tree nuts, shellfish, fish, eggs, soy, wheat, and milk. The first four foods listed may cause life-threatening reactions. If the patient states that he or she has a food allergy, the interviewer should ask what happens when those foods are eaten. Allergic symptoms may affect the respiratory tract (rhinorrhea, sneezing, wheezing, chest tightness, laryngeal edema), skin (urticaria, angioedema, pruritus, erythematous macular rash), or GI tract (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramping).

A food allergy needs to be differentiated from food intolerance. Symptoms of food intolerance are usually confined to the GI tract and may be acute or chronic. Upper GI tract symptoms of belching and bloating may be due to aerophagia (swallowing air during the ingestion of food or drink), which is commonly associated with smoking, eating rapidly or talking while eating, chewing gum and hard candy, or ingesting carbonated beverages. Chronic lower GI tract symptoms of bloating, cramping, flatulence, or diarrhea may result from the ingestion of sugar substitutes (sorbitol, xylitol) or fructose, high fiber intake, or lactase deficiency. Of these potential causes, lactose intolerance is the most common, affecting 25% of the population in the United States and up to 80% of African Americans. In lactose-intolerant individuals, symptoms occur after the consumption of products containing lactose, including milk, cheese, ice cream, yogurt, and some processed foods.

Social History

Multiple social factors affect the dietary and nutritional status of patients. For example, low socioeconomic status, low fixed income, homelessness, food insecurity (the uncertainty of having or being able to acquire enough food because of insufficient funds or other resources) or lack of access to a variety of food choices may contribute to nutritional deficiencies. Chronic alcoholism and recreational drug use are two additional conditions that put people at high nutritional risk. The patient’s attitudes about food and nutrition, as well as religious observances, also determine eating patterns and the selection or avoidance of specific foods. This information is important to note and document.

Lifestyle Habits

The lifestyle habits section of the medical history includes the dietary history, physical activity history, alcohol use history, and smoking history. Questions related to alcohol use and smoking are discussed in Chapter 1, The Interviewer’s Questions.

Dietary History

The dietary history provides information about the patient’s food habits, diet, and any counseling he or she may have received. Depending on the patient’s medical problems, the dietary history may be brief or comprehensive. It is often difficult to obtain accurate information about a patient’s diet because of variability, general lack of focus on what is eaten, and forgetfulness. For this reason, the primary goal is to obtain a qualitative description of eating patterns and the foods and beverages that are habitually chosen, along with any dietary changes that occurred over the course of the illness. Three methods are commonly used: a 24-hour intake recall, a typical day, and food frequency.

A 24-hour intake recall is used extensively and may be broached as follows: “Please tell me what you had to eat and drink for the entire day yesterday. Could you start with the first item you had to eat or drink and bring me through the entire day? I would also like to know the times you ate and the amounts.” The advantage of this method is that patients can usually remember what they ate over the course of one recent day. The disadvantage is that one particular day may not adequately depict the patient’s usual diet, especially if there has been a recent change.

The preferred method is to ask the patient to describe a typical day. A good opening is, “I would like to know about your usual or typical diet. Can you bring me through a typical day, starting with the first item you eat or drink? I would also like to know the times you eat and the amounts.” The advantage is that you are more likely to capture a picture of the patient’s habitual diet. If the patient states that every day is different and there are no typical days, then ask him or her to describe one or two days as examples, such as one weekday and one weekend day. Note that in both of these methods the diet history is taken using an “open-ended” question. Patients are not asked what they ate for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Anchoring food intake to predefined meals may bias the patient to provide an inaccurate history.

The third method is food frequency. This refers to how often the patient consumes specific food groups or nutrients and about other dietary practices. Examples of questions are “How often do you eat fruits and vegetables: daily, every few days, weekly, or rarely?” and “When you do eat them, how many servings do you choose?” The same qualitative questions can be extended to the consumption of dairy products, whole-grain breads and cereals, red meats, visible fats, and so forth. Examples of other informative questions for taking a dietary history are as follows:

“What are your favorite foods and snacks?”

“How often are meals home cooked? Who prepares the meals?”

“What sort of fats or oils (if any) do you use in cooking?”

“How is food usually prepared (baked, broiled, fried, boiled, steamed, poached)?”

Targeted, disease-focused questions should be asked, depending on the patient’s medical history. For example, if the patient has osteoporosis, you would probe for the consumption of calcium-containing foods such as milk, cheese, sardines, and greens. For a patient with hypercholesterolemia or coronary artery disease, you would ask about the intake of saturated fats, whole dairy products, egg yolks, fried foods, tropical oils, and fiber sources. For a patient with diabetes mellitus, you would ask whether meals and snacks are timed to correspond with insulin injections, whether the patient follows the American Diabetes Association food group exchange system and counts carbohydrate grams, and whether the patient knows symptoms of hypoglycemia and how to treat it.

Patients should be asked whether they read nutrition labels and, if they do not, they should be instructed how to read them. Since May 1994, nutritional labeling has been required for almost all foods. There are now uniform definitions for the terms “free,” “low,” “light,” “reduced,” “high,” “lean,” “extra lean,” and so forth. The current food label, known as Nutrition Facts, allows individuals to choose healthier foods more easily. Nutrition labeling provides the “% Daily Value,” which shows how a food fits into the overall daily diet. This value is based on a 2000-calorie diet and informs the individual whether the food is high or low in the specific nutrient. These labels must include serving size, total calories, calories from fat, total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium, total carbohydrate, dietary fiber, sugars, and protein. The % Daily Value of four key vitamins and minerals (vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and iron) is also mandatory on these labels. Information about other vitamins and minerals is optional. Information about thiamine, riboflavin, and niacin is no longer necessary because deficiencies of these vitamins are rare in the United States. The % Daily Value is only a guide; if a patient eats more than 2000 calories a day, the food would contribute a lower % Daily Value to the diet.

The Institute of Medicine of the National Academies recommends that the following guidelines be used daily for achieving a healthful diet:

Carbohydrates: 45% to 65% of calories

Fat: 20% to 35% (<10% saturated fat)

Trans fat: no more than 1% total body calories

Protein: 10% to 35% of calories

Most individuals on a balanced diet consume foods that contain all the vitamins and minerals they need. Some individuals, however, might benefit from vitamin supplementation. These individuals include habitual dieters, ill patients (especially those with loss of appetite or impaired absorption), pregnant or lactating women, infants consuming formula, some vegetarians, older patients, and patients with anorexia nervosa.

Physical Activity

Both nutrition and regular physical activity play an important role in the overall health of the individual. It is recommended that all adults perform at least 150 minutes of moderately intense physical activity per week, or approximately 30 minutes 5 days a week. There are many benefits to regular physical activity: increasing physical fitness; building and maintaining healthy bones, muscles, and joints; improving endurance and muscle strength; lowering the risk of certain diseases (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease, colon cancer); controlling blood pressure; promoting and improving a sense of well-being; reducing feelings of anxiety and depression; and managing weight problems.

Always ask patients about their current level of physical activity and functioning. Some helpful questions include the following:

“What is the most physically active thing you do in the course of the day?”

“How do you spend your working day and leisure time?”

“What types of physical activity do you enjoy? How often do you do them?”

“Do you exercise regularly?” If so, “What exercises do you do regularly? How often?”

“What gets in the way of you consistently doing physical activity?”

“How many hours of TV do you watch every day?”

“How many hours are you at a computer or desk every day?”

“Do you belong to (and attend) a health club or exercise classes?”

Review of Systems

The review of systems section is a reexamination of the patient’s history by organ system. This section should include a general statement about the patient’s body weight history and appetite if such a statement is not included in the history of present illness or the past medical history.

Physical Examination

Vital Signs

Along with recording the patient’s heart rate, pulse, blood pressure, and temperature, you should also routinely record the patient’s height and weight. Height and weight, although not typically considered true “vital signs,” provide significant information about the patient’s overall health status and are frequently used for medication dosing. Height and weight should be measured, if possible, although estimated measurements are better than no values at all. If values are estimated, you should record these as reported rather than measured values. Body weight varies with hydration status and the presence of clothing or wet dressings. Always measure the patient’s height in stocking feet. Conditions that affect fluid balance such as renal or liver failure or congestive heart failure also affect body weight.

The nutritional status of the patient based on height and weight is interpreted by the body mass index (BMI). BMI is an international designation of relative weight for stature and is a more reliable index of obesity than are the older height-weight tables. It is calculated in one of the two following ways:

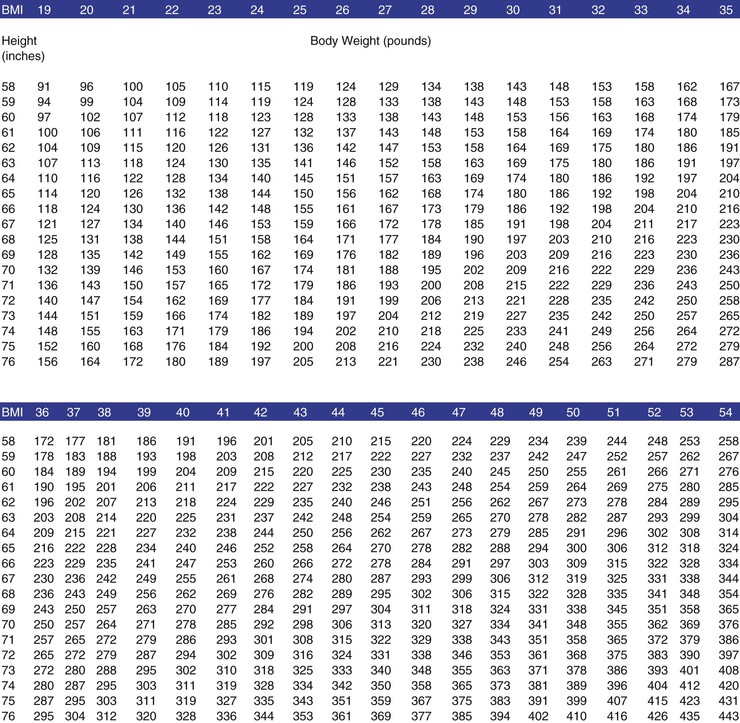

The advantage of BMI is that it is relatively easy to calculate and can be readily used for comparisons between women and men and persons of different heights. BMI can easily be determined from tables, as shown in Figure E29-1.

Figure E29–1 Body mass index (BMI) table. To find a specific BMI, (1) look down the left column to find the height (measured in inches); (2) look across that row and find the weight; and (3) look to the top of the column to find the number that is the BMI.

A disadvantage of using BMI is that it does not directly measure body composition and therefore may yield a spurious interpretation. For example, a malnourished patient with excessive fluid retention may be miscategorized as having a healthy BMI, or a muscular body builder may be classified as obese. A person with a BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2 is considered underweight; a person with a BMI between 18.5 and 25 is considered to have a healthy weight; a person with a BMI between 25.1 and 29.9 is considered overweight; and a person with a BMI of 30 or more is considered obese.

If the person’s BMI is equal to or greater than 35, it is important to measure the waist circumference just above the hips. If the waist circumference is 35 inches or more in women or 40 inches or more in men, the risk of developing hypertension, type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, and stroke increases significantly. Such individuals may have the metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a name for a group of risk factors that occur together and increase the risk for the disease indicated. The metabolic syndrome is becoming more and more common in the United States. It is not known whether the syndrome is due to one single cause, but all of the risks for the syndrome are related to obesity. The two most important risk factors for metabolic syndrome are:

Other risk factors include:

People who have metabolic syndrome often have two other problems that can either cause the condition or make it worse:

Appearance

A description of the patient’s general appearance is always found at the beginning of the physical examination report; for example, “On examination, Ms. B. is a well-developed, thin, white female.” Other nutritionally descriptive terms are as follows:

Nutrition-oriented aspects of the physical examination focus on the skin, eyes, mouth, skeletal muscle, and fat stores. The skin provides an excellent barometer of clinical nutrition and is accessible to the health care provider in its entirety. Chronic wasting associated with loss of subcutaneous fat from calorie or protein deficiency results in a fine wrinkling of the skin. Easy bruising may result from vitamin deficiencies. In areas of the skin where sebaceous glands are dense, such as the nasolabial folds, neck, cheeks, and forehead, a deficiency of essential nutrients may result in disturbance of their secretory function and blockage of their ducts with plugs of dried sebum. Around hair follicles, there may be accumulations of keratin associated with vitamin and fatty acid deficiencies. Edema may result from protein deficiencies. This occurs as a consequence of low plasma albumin and a reduced oncotic pressure. Excessive skin pigmentation may also be seen. In deficiencies of niacin or tryptophan, increased pigmentation occurs in areas of skin exposed to the sun. Changes in the hair and nails are also common in nutritional deficiencies. Blindness may result from vitamin A deficiency. Fissuring of the lips is indicative of riboflavin deficiency. The tongue may be large in iodine or niacin deficiency. Some of the more common physical signs of nutritional deficiency are listed in Table 29-4.

Table 29–4

Common Manifestations of Nutritional Deficiencies

| Site | Sign | Deficiency |

| Skin | Dry and scaly, cellophane appearance | Protein (see Fig. E29-5) |

| Flaking dermatitis | Zinc (see Fig. E29-12) | |

| Follicular hyperkeratosis | Vitamin A (see Fig. E29-7) | |

| Pigmentation changes | Niacin (see Fig. E29-11) | |

| Petechiae | Vitamin C (see Fig. E29-9) | |

| Purpura | Vitamin C (see Fig. E29-9), vitamin K | |

| Pallor | Iron, vitamin B12, folate | |

| Eyes | Night blindness | Conjunctiva pallor |

| Vitamin A | Iron, vitamin B12, folate | |

| Mouth | Angular stomatitis | Riboflavin, pyridoxine, niacin |

| Cheilosis (dry, cracking, ulcerated lips) | Riboflavin, pyridoxine, niacin | |

| Glossitis | Riboflavin, niacin, B vitamins, iron, folate (see Fig. E29-10) | |

| Bleeding gums | Vitamin C (see Fig. E29-8), riboflavin | |

| Muscles | Interosseous muscle atrophy, squaring off of shoulders, poor hand grip and leg strength | Protein, calories (see Fig. E29-5) |

Special Populations

Obese Patients

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2010, 69.2% of adult Americans, representing more than 100 million individuals, are classified as overweight or obese (defined as a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher). Among the general population, 33.3% are considered overweight (BMI of 25 to 29.9), and 35.9% are considered obese (BMI of 30 or higher). Thus obesity represents the most significant diet-related health problem encountered by health care professionals.

Several lifestyle factors may predispose to obesity. When calorie intake continuously exceeds requirements, obesity results. The converse is likewise true. Fewer than 1% of all cases of obesity are related to neuroendocrine causes, and these conditions rarely cause massive obesity. These syndromes include hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, adrenocortical excess, polycystic ovary syndrome, and hypothalamic tumors or other damage to this part of the brain, as well as some rare inherited conditions. Prader-Willi syndrome is a rare chromosomal microdeletion syndrome associated with childhood massive obesity, mental retardation, and failure of sexual development. A patient with Prader-Willi syndrome and morbid obesity is pictured in Figure E29-2.

Figure E29–2 Patient with Prader-Willi syndrome.

Obesity-Focused History

An obesity-focused history should include a chronologic history of the patient’s weight, identifying age at onset, description of weight gain, and inciting events. For women, weight gain often occurs during adolescence, pregnancy, child-rearing years, and menopause. For many patients, weight gain occurs with smoking cessation or other changes in lifestyle, such as changes in marital status, occupation, or housing. The patient’s history may be suggestive of, as already mentioned, several endocrinologic causes for weight gain. With the exception of polycystic ovary syndrome, these conditions are uncommon causes of obesity. Several medications are known to cause weight gain as an unintended side effect. The most common drug groups are antidepressants (tricyclic agents and mirtazapine), lithium, antipsychotics (phenothiazines, butyrophenones, olanzapine, clozapine, and risperidone), anticonvulsants (valproic acid, carbamazepine), steroid hormones (corticosteroid derivatives, megestrol acetate, estrogen), and antidiabetics (insulin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones).

“When did you first consider yourself overweight or have a weight problem?”

“What was your lowest weight as an adult?”

In addition to characterizing the chronologic history of the patient’s weight, it is important to appreciate what effect the obesity has had on the patient. Obesity may affect the physical and mental health functioning of the patient, both of which are important aspects of quality of life. Physical effects of obesity include difficulties with mobility, such as bending, kneeling, and stair climbing; mental health effects may include low self-esteem, poor body image, shame, and social isolation. You should also ascertain whether the patient participated in any weight management programs in the past and what the response to treatment was. You can obtain this information through the following questions:

Obesity-Focused Physical Examination

According to the most recent National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1998) guidelines, assessment of risk status according to overweight and obesity is based on the patient’s BMI, waist circumference, and existence of comorbid conditions.

Being overweight or obese substantially increases the risk of morbidity and mortality from hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, stroke, gallstones, osteoarthritis, respiratory problems (including sleep apnea), several cancers, and the metabolic syndrome, which is a clustering of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Factors characteristic of this syndrome are abdominal obesity, elevated triglyceride levels, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, raised blood pressure, and impaired fasting blood glucose.

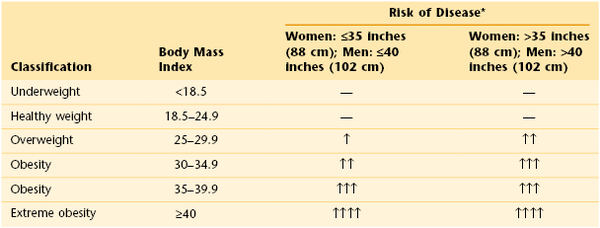

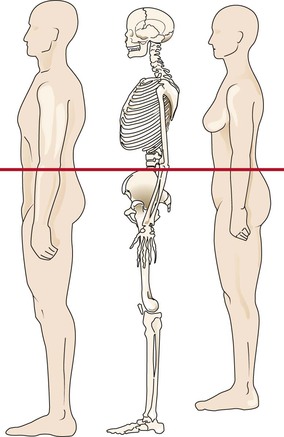

Excess abdominal fat, a hallmark of the metabolic syndrome (described earlier in this chapter), can be clinically defined as a waist circumference greater than 40 inches (102 cm) in men and greater than 35 inches (88 cm) in women. Lower waist circumference thresholds have been recommended for the Asian population. To measure waist circumference, a horizontal mark is drawn just above the uppermost lateral border of the iliac crest. A cloth or metal tape is then placed in a horizontal plane around the abdomen at the level of the mark (Fig. E29-3). The measurement is made at a normal minimal respiration. An increased waist circumference can indicate increased risk even at a healthy weight. In contrast, waist circumference is less useful as an independent marker of medical risk when the BMI is greater than 35. Table 29-5 lists the classification of weight status and risk of disease.

Table 29–5

Classification of Weight Status and Risk of Disease

* Waist circumference is measured just above the iliac crest. An increased waist circumference may indicate increased disease risk even at a normal weight.

Adapted from National Institutes of Health and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults, Rockville, Md, 1998, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

The physical examination process for patients with obesity is identical to that for other adult patients, with the exception of specific measures to determine the obesity category (height, weight, and waist circumference) and the use of an appropriate blood pressure cuff. A bladder cuff that is not the appropriate width for the patient’s arm circumference can cause a systematic error in blood pressure measurement; if the bladder is too narrow, the pressure will be overestimated and lead to a false diagnosis of hypertension. The most frequent error in measuring blood pressure is “miscuffing,” with undercuffing large arms accounting for 84% of the “miscuffings.” To avoid errors, the “ideal” cuff should have a bladder length that is 80% and a width that is at least 40% of arm circumference (a length-to-width ratio of 2 : 1). Therefore a large adult cuff (16 × 36 cm) should be chosen for patients with mild to moderate obesity (or arm circumference of 14 to 17 inches [36 to 43 cm]) whereas an adult thigh cuff (16 × 42 cm) must be used for patients whose arm circumferences are greater than 17 inches.

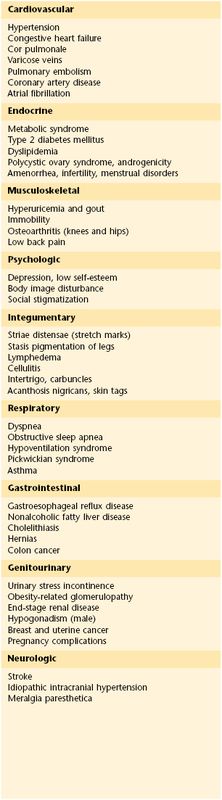

When the interviewer completes the review of systems section of the history and performs the physical examination, it is important to have a high index of suspicion for obesity-related diseases. Clinically, obesity affects at least nine organ systems. Obesity has been linked with an increased risk of breast and endometrial cancers in women. The mechanism is thought to be related to increased circulating estrogens as a consequence of increased conversion of androgens to estrogens in adipose tissue. Obesity increases the risk of gallstone formation by increasing gallbladder volume and bile stasis. Increased cholesterol production is also thought to play a role. Degenerative joint disease is seen in obese individuals more frequently than in persons of normal weight. Regardless of whether it is a causative factor, osteoarthritis aggravates joint symptoms. A positive association has been noted between serum triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and obesity. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol level tends to be lower in patients with obesity. The Pickwickian, or obesity-hypoventilation, syndrome is characterized by marked obesity, somnolence, periodic apnea (transient cessation of breathing), chronic hypoxemia (deficient oxygenation of the blood), hypercapnia (carbon dioxide retention), and polycythemia (increased number of red blood cells). Table 29-6 lists the symptoms and diseases that are directly or indirectly related to obesity. Although individuals vary, the number and severity of organ-specific comorbid conditions usually rise with increasing levels of obesity.

Malnourished Patients

Malnutrition (which is synonymous with undernutrition) is associated with slower wound healing, increased number of medical complications, longer length of hospital stay, higher health care costs, and increased mortality rate. By performing a nutritionally focused history and physical examination, you can identify individuals who are at high nutritional risk or are malnourished. Key elements from the history and physical examination were reviewed earlier in this chapter.

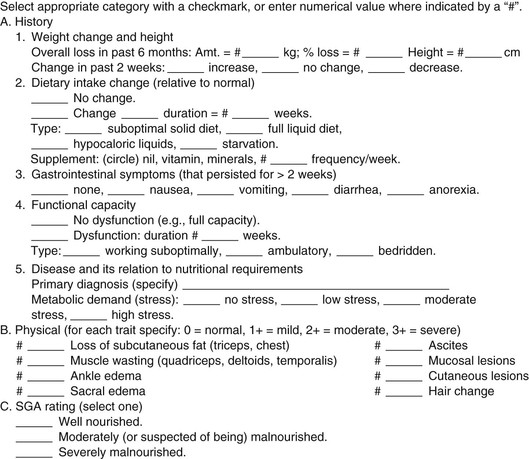

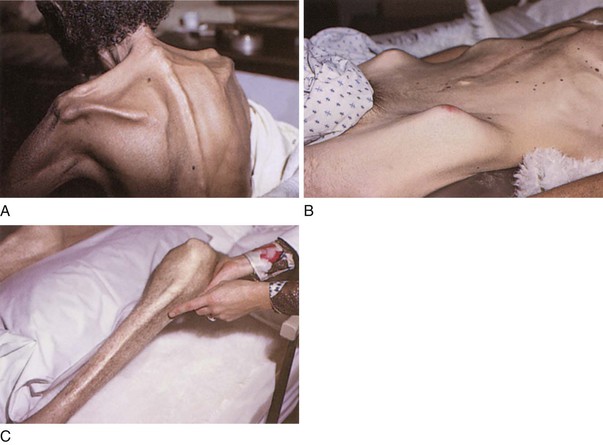

There is currently no single, universally accepted approach to the diagnosis of adult malnutrition; however, the subjective global assessment provides an integration of historical and physical examination data to arrive at an evaluation of the patient’s nutritional status. As shown in Figure E29-4, five features of the history and eight features of the physical examination are combined to assess risk. The historical features are weight loss, changes in dietary intake, significant GI symptoms, functional status or energy level, and metabolic demand of the patient’s underlying disease state. Physical findings are scored as normal (0), mild (1+), moderate (2+), or severe (3+), and include depletion of subcutaneous fat in the chest and triceps, muscle wasting in the quadriceps and deltoid muscles, and the presence of edema or ascites. On the basis of the history and physical examination findings, patients are ranked according to the following three categories: A, good nutrition; B, moderate or suspected malnutrition; and C, severe malnutrition. Weight loss, poor dietary intake, loss of subcutaneous tissue, muscle wasting, and functional impairment are considered the most significant factors. These nutritional categories can be used to classify the severity of nutritional risk and the need for intervention. In addition, a low BMI, generally less than 19, should be considered an important predictor of mortality in a hospitalized patient. Figure E29-5 depicts three patients with protein-energy malnutrition, or deficiency of macronutrients. Note the severe loss of subcutaneous fat reserves and muscle mass and the prominence of the bones.

Figure E29–4 Subjective global assessment. Reprinted with permission from Jeejeebhoy KN: Clinical and functional assessments. In Shils ME, Olson JA, Shike M, Eds: Modern nutrition in health and disease, 8th ed. Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1994, p. 805.

Figure E29–5 A to C, Loss of subcutaneous fat and muscle in three patients with protein-energy malnutrition.

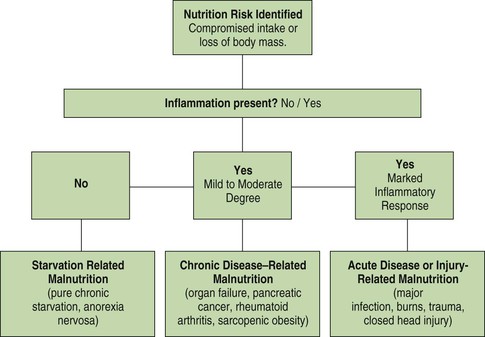

Impairment of function secondary to loss of body protein and energy reserves along with identifying presence or absence of systemic inflammation is the most important component of the assessment of nutritional risk. You can evaluate function while performing the physical examination and by watching the patient’s activity. You can assess grip strength by asking the patient to squeeze your index and middle fingers hard for at least 10 seconds. You can assess respiratory muscle function by asking the patient to exhale quickly or cough deeply. Shortness of breath may be noted at rest. You can assess leg muscle strength by asking the patient to push his or her legs and feet against your hand and by watching the patient ambulate. Indicators of inflammatory response include elevated C-reactive protein, white blood count, and blood glucose levels. Based on the patient’s nutritional status and presence or absence of inflammation, an etiologic factor–based diagnosis of malnutrition and nutritional risk can be made as shown in Figure E29-6.

Older Adult Patients

Older adults represent a diverse group who are at specific risk for a variety of nutritional problems. These problems are caused by a combination of environmental, social, and economic factors and are compounded by numerous physiologic changes that occur at different rates as individuals age. The Nutrition Screening Initiative, a multidisciplinary effort to promote nutrition screening and better nutritional care in America’s health care system, has identified the following risk factors associated with poor nutritional status in older Americans: inappropriate food intake, poverty, social isolation, dependency or disability, acute or chronic diseases or conditions, and chronic medication use.

These factors have been incorporated into a risk factor checklist with the acronym DETERMINE, which identifies several warning signs for individuals at risk for poor nutritional status:

• Multiple medications or drugs: Drugs and other medications can depress the appetite and alter nutrient absorption and excretion. Drugs can further alter the sense of taste and smell, change the secretion of saliva, irritate the stomach, and cause nausea. Some drugs can contribute directly to dietary deficiencies; for example, antacids absorb folic acid and calcium, laxatives absorb fat-soluble vitamins, and aspirin increases the excretion of folic acid.

• Involuntary weight loss or gain: Assess changes in weight.

• Need for assistance with self-care: Assess self-care practices.

• Elderly years: Patients older than 80 years are considered “elderly.”

Specific nutritional interventions are vital components of the health care delivery system for older patients. The older person may overeat as a way of coping with feelings of loneliness. Some of these individuals, however, can be overweight but malnourished; their diet consists of cake and candy, which are high in calories but low in nutrients. The National Institute on Aging suggests that the daily diet for the geriatric population include the following:

Clinicopathologic Correlations

There are myriad vitamin and trace element deficiencies, and it is beyond the scope of this book to describe them. There are, however, several worth considering.

Vitamin A, a fat-soluble vitamin, is an integral component of rhodopsin and iodopsin, the light-sensitive proteins in the rods and cones of the retina. A deficiency of vitamin A is associated with follicular hyperkeratosis and night blindness. Figure E29-7 illustrates a patient with vitamin A deficiency and follicular hyperkeratosis.

Figure E29–7 Effects of vitamin A deficiency.

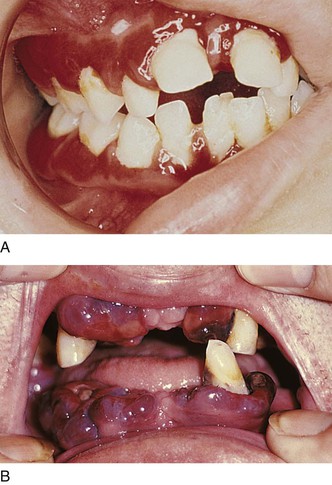

Vitamin C, or ascorbic acid, is a biologic antioxidant and free radical scavenger. The biosynthesis of bile acids, collagen, and norepinephrine, as well as the normal functioning of the hepatic oxygenase system, depends on these antioxidant properties. Vitamin C deficiency is rarely found in the United States. The classic deficiency state is known as scurvy. It is characterized by depression, fatigue, and widespread abnormalities in connective tissue. Oral lesions (including inflamed gingiva), petechiae, hemorrhage, impaired wound healing, hyperkeratosis, and bleeding into body cavities are commonly seen. Figure E29-8 depicts marked periodontal disease in two patients with scurvy. Figure E29-9 illustrates perifollicular purpura and ecchymoses in a patient with vitamin C deficiency.

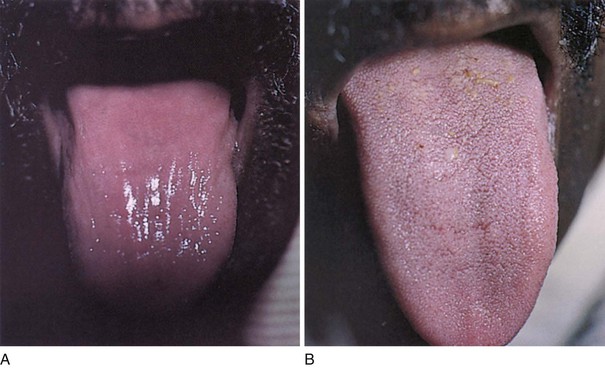

Folate is required for the synthesis of nucleotides and the metabolism of several amino acids. The inhibition of folate metabolism in bacteria and in cancer cell growth is the mechanism of action of the sulfonamide antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents such as methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil. Folate deficiency is seen in women of childbearing age and in alcoholic patients. It manifests with a megaloblastic anemia reflecting ineffective DNA synthesis. Depapillation of the tongue and diarrhea are common findings. Figure E29-10A depicts the classic glossitis of folate deficiency in an alcoholic patient; Figure E29-10B illustrates the patient’s tongue after folate replacement.

Figure E29–10 Tongue of a patient with folate deficiency. A, Before folate therapy. B, After folate therapy.

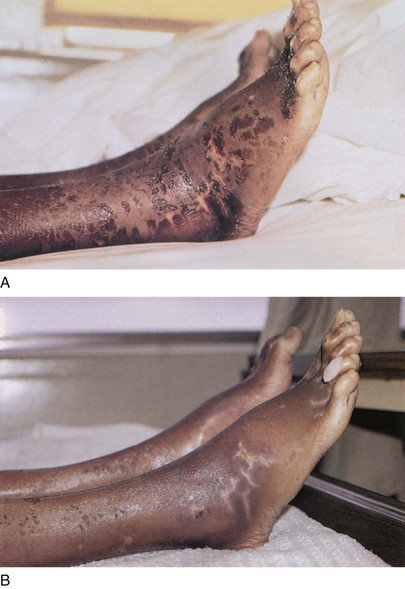

Niacin, a B-complex vitamin, is required as a coenzyme to form nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. There are more than 200 enzymes that require the active coenzyme forms of niacin as electron acceptors or hydrogen donors. The classic deficiency of niacin is pellagra. It is seen in populations in China, Africa, and India, where rice is the major source of energy. The most common symptoms are diarrhea, dementia, and pigmented dermatitis in sun-exposed areas. Glossitis, stomatitis, vertigo, and burning paresthesias are also common. Figure E29-11A illustrates marked pigmented dermatitis secondary to niacin deficiency in an alcoholic patient; Figure E29-11B depicts the skin of the same patient after replacement therapy.

Figure E29–11 Legs and feet of a patient with niacin deficiency. A, Before niacin therapy. B, After niacin therapy.

Zinc is a trace element needed for a variety of metabolic processes. It is a component of more than 100 enzymes, including DNA polymerase, RNA polymerase, and transfer RNA synthetase. Zinc deficiency is associated with growth retardation and hypogonadism in children. In adults, infertility, poor wound healing, diarrhea, and dermatitis are frequent symptoms. Figure E29-12A illustrates a widespread scaling dermatitis secondary to zinc deficiency in a patient with fat malabsorption; Figure E29-12B illustrates the patient’s skin after treatment with zinc.

Concluding Thoughts

The public is fascinated with weight reduction and is quick to buy books on fad diets, take over-the-counter dietary supplements, and try new “cures” for disease. Most of these do little for patients except cost them money. Instead, a good health care provider should inform patients how to eat healthily. Any good diet should accomplish the following:

• Include a wide variety of foods to ensure adequate amounts of all essential nutrients

• Educate the person about proper nutrition

• Be based on sound biochemical facts

For health care providers, dealing with patients who are following diets of questionable nutritional value requires tact and skill. Your success often depends more on how you meet the patient’s emotional needs than on your academic credentials. Always be informed about contemporary fad diets and cures. Discuss them openly with the patients; never condemn them out of your ignorance or unwillingness to learn about them.

Nutritional assessment does not stand alone as a separate process; it must be integrated into the entire history and physical examination. The depth of the assessment and the information recorded depend on the patient’s specific medical problems. This chapter has provided the framework for integrating key nutrition-related questions and considerations into patient evaluations.

Bibliography

American Medical Association. How to talk with your patients about their weight. [Available at] http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/public-health/talking-about-weight-kushner.pdf; June 2011 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Bailey DG, et al. Grapefruit juice-drug interactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:101.

Barrocas A, et al. Nutritional assessment: practical approaches. Clin Geriatr Med. 1995;11:675.

Bauer BA. Herbal therapy: what a clinician needs to know to counsel patients effectively. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:835.

Eisenberg DM. Advising patients who seek alternative medical therapies. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:61.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491.

Gazewood JD, Mehr DR. Diagnosis and management of weight loss in the elderly. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:19.

Grapefruit juice interactions with drugs. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2004;37(955):73–74.

Grundy SM, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433.

Hark L, Morrison G. Medical nutrition and disease: a case-based approach. ed 3. Blackwell Science: Malden, Mass; 2003.

Haskell WL, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1423.

Heimburger DG. Nutrition needs and assessment during the life cycle. Adulthood, Chapter 53. Shils ME, Shike M, Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ. Modern nutrition in health and disease. ed 10. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia; 2006.

Jenson GL, et al. Malnutrition syndromes: a conundrum vs continuum. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33:710.

Joshipura KJ, et al. The effect of fruit and vegetable intake on risk for coronary heart disease. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1106.

Kriepe RE. Eating disorders among children and adolescents. Pediatr Rev. 1995;16:370.

Kushner RF. Roadmaps for clinical practice: case studies in disease prevention and health promotion-assessment and management of adult obesity: a primer for physicians. American Medical Association: Chicago; 2003.

Lankisch PG, Gerzmann JF, Lehnick D. Unintentional weight loss: diagnosis and prognosis. The first prospective follow-up study from a secondary referral centre. J Int Med. 2001;249:41.

Manson JE, et al. Body weight and mortality among women. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:677.

Marcoe K, et al. Development of food group composites and nutrient profiles for the My Pyramid food guidance system. J Nutr Edu Behav. 2006;38:S93.

Maskalyk J. Grapefruit juice: potential drug interactions. CMAJ. 2002;167:279.

Mehler PS. Diagnosis and care of patients with anorexia nervosa in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1048.

Morgan JF, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: a new screening tool for anorexia nervosa. West J Med. 2000;172:164.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2005–2006. [Available at] www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/nhanes2005-2006/nhanes05_06.htm; Updated August 29, 2013 [Accessed September 15, 2013] .

National Institutes of Health and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service: Rockville, Md; 1998.

National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and North American Association for the Study of Obesity (NAASO). Practical guide to the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. [NIH publication no. 00-4084] National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, Md; 2000.

Pennachio DL. Drug-herb interactions: how vigilant should you be? Patient Care. 2000;15:41.

Pickering TG, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111:697.

Popkin BM, Siega-Riz AM, Haines PS. A comparison of dietary trends among racial and ethnic subgroups in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:716.

Reife CM. Involuntary weight loss: common medical problems in ambulatory care. Med Clin North Am. 1995;70:299.

Silk AW, McTighe KM. Reexamining the physical examination for obese patients. JAMA. 2011;305(2):193.

Stallings VA, Yaktine AL. Nutrition standards for foods in schools: leading the way toward healthier youth. National Academies Press: Washington, DC; 2007.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary guidelines for Americans 2010. ed 7. U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC; 2010.

Walsh BT, Devlin MJ. Eating disorders: progress and problems. Science. 1998;280:1387.

White JV, et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Dietetics. 2012;112(5):730.

Wynder EL, Stellman SD, Zang EA. High fiber intake: indicator of a healthy lifestyle. JAMA. 1996;275:486.

1 This chapter was written in collaboration with Robert F. Kushner, MD, Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

ounces per day)

ounces per day) cups per day)

cups per day)