53 Assessment and Avoiding Complications in the Scoliotic Elderly Patient

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Scoliosis — defined as a curvature of the spine in the coronal plane measuring over 10 degrees — can be found in the adult population and can be a significant source of disability, especially in the elderly.1,2 There are three principal forms of scoliotic spinal deformity that can be described: idiopathic, i.e., that whose development can be found during the juvenile or adolescent growing years of life and which persists into adulthood; de novo, which involves the development of a new scoliosis later in life as a result of degenerative changes in the lumbar spine; and osteoporotic scoliosis, a less common form of spine curvature secondary to osteopenic collapse of vertebral bodies.

In the adolescent with scoliosis, the primary focus of treatment is the deformity and concerns of curve progression. In the older patient, it is much more common that pain is the primary complaint.3,4 In the later decades of life, curve progression becomes less and less of a concern, primarily because of the restraint provided by the degenerating and ossifying disc spaces and the arthritic facet joints. Being out of balance, especially in the sagittal plane, adds an element of posturally related fatiguing pain that limits patients’ ability to perform upright activities.5 Older adults are most commonly symptomatic in the lower thoracolumbar or lumbar region, due to the age-related disc degeneration and osteoarthritis associated with the deformity.

Surgery

Elderly patients undergoing surgery for scoliosis face the prospect of increased morbidity and mortality compared with their younger counterparts, primarily because they enter into the surgery much more disabled and with worse health status.6–8 In the preoperative assessment, careful attention should be paid to their cardiac and pulmonary systems, as many patients have become quite sedentary and the stress of surgery may thus become problematic. If patients smoke, they should be encouraged to quit at least a number of weeks before the operation, not only to improve the chances of bone healing but to lessen the likelihood of pulmonary and wound complications, which are already elevated in the elderly population. If there is a suspicion of respiratory compromise, a history of smoking, or planned procedures about the diaphragm, preoperative pulmonary function should be assessed.

Similarly, if elderly patients have a history of cardiac or ischemic disease, they should undergo preoperative stress testing and formal cardiac evaluation. It is recommended that the elderly who have concomitant diagnoses of either hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes be considered for perioperative beta-blockers.9

Elderly patients may have become relatively malnourished and the associated risks of sepsis, wound breakdown, etc., are well established.9 Total parenteral nutrition should be considered in staged surgical treatments, as it has been shown to diminish the rate of nutritional depletion and postoperative infections.

Surgical Techniques

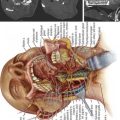

Unlike in the adolescent, where maximal safe correction of the coronal plane curvature is sought, in the elderly, aside from obtaining a solid arthrodesis, much more critical than Cobb angle correction is the obtaining and maintenance of appropriate balance in both the coronal and sagittal planes. A stable and balanced spine is the principal goal of deformity surgery in the elderly, and this often involves accepting less curvature correction. Numerous studies have emphasized that the component of postoperative radiography most closely tied to overall clinical success is the achievement of adequate balance, especially in the sagittal plane. Glassman and other members of the Spine Deformity Study Group, in a review of nearly 300 patients, have suggested that restoration of the normal sagittal balance is the most critical goal for any reconstructive spine surgery.5 A plumbline dropped from C7 should fall in the middle of the sacrum in the coronal plane and within the disc space of the lumbosacral articulation in the lateral view. Older adults have typically developed pronounced disc degeneration and narrowing, which leads to a loss of the normal lumbar lordosis and a forward drift of the sagittal plumbline. Osteopenic compression-type fractures can worsen the sagittal alignment, as can any thoracolumbar kyphosis.10 For these reasons, fusions of primarily lumbar pathology may well need to be extended proximally into the upper thoracic spine.

With the increased use of pedicle-screw fixation and advancing techniques such as vertebral resections, the majority of surgery in the elderly is performed through the posterior approach.11 This would even include access to the anterior column, e.g., the intervertebral discs via posterior or transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF or TLIF, respectively). Interbody support at the lumbosacral junction within at least the lower two spaces, L4-5 and L5-S1, is biomechanically mandatory for successful fusion rates.12–14 Support here lessens the strain seen on the posterior instrumentation and protects to a certain degree against pull-out failure. As a general rule, but especially in the elderly, instrumentation should be used to maintain correction, not obtain correction.

Pedicle screws have become the primary method of fixation in deformity surgery, including the elderly, although their bone quality still remains a concern. Pull-out strength of pedicle screws in patients with normal bone density is typically about 1400 N; however, in patients with osteoporosis, the strength can be as low as 200 N.15 Fixation strength of pedicle screws has been correlated with insertional torque. Hence, it is recommended that, in order to obtain some purchase with the inner cortical wall of the osteopenic pedicle, the largest-sized screw that can comfortably be placed be chosen. This is another reason for careful assessment of preoperative computed tomography with measurement of the inner diameters of the pedicles. In settings of reduced purchase quality, many surgeons treating the elderly may reinforce pedicle screws with adjacent laminar hooks or sublaminar wires. Of note, in the elderly spine, compared with younger adolescent patients treated for scoliosis, the transverse processes are typically quite brittle, and, with few exceptions, are not commonly recommended as points of principal fixation for instrumentation such as hooks.

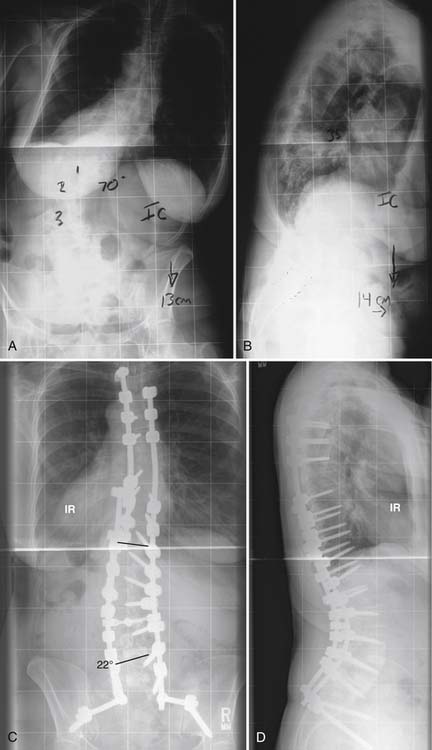

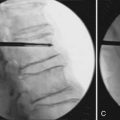

Fixation into the sacrum is a particular problem as the quality of the bone is probably the poorest here, and the risk of fusion failure (pseudarthrosis) may be one of the highest.16,17 This is another reason why combined anterior and posterior surgery is recommended for long fusions down to the sacrum or the ilium: at a minimum, L4-5 and L5-S1 require strong structural support. In addition, because of the risk of osteopenic fracture of the sacrum when long fusions extend distally, supplemental iliac fixation is highly recommended (Figure 53-1).18

Screws fixed into the sacrum can be directed down the S1 pedicle to the anterior cortex or the sacral promontory where the bone is most dense. Alternatively, they can be directed 30 degrees laterally out into the thickest part of the sacral ala. Either way, it is important to try to perforate and actually gain purchase into the anterior cortex with the screw threads, which will increase the holding power of the screw significantly.19 Cancellous screws are preferred over cortical ones as the strength of purchase correlates directly with the amount of bone found between the screw threads.

Osteoporosis and Scoliosis

There exists a known association between scoliosis and osteoporosis.20,21 Two studies of osteoporotic women have described an incidence of scoliosis between 35% and 45%.9,22,23 The majority of these curves will progress somewhat because of a combination of disc degeneration and facet overloading as well as compression of the osteopenic bones within the apices of the curves.20,22

It is important to have an appreciation for the quality of the elderly patient’s bone before planning deformity correction that involves the implantation of instrumentation; it is difficult to accurately quantify the degree of osteopenia with plain radiographs before significant quantities of bone are lost.24 Accurate assessment of bone mineral content includes quantitative computerd tomography (QCT), dual-photon absorptiometry (DPA), or dual-energy radiography (DXA).

Multiple surgical techniques have been suggested to improve fixation strength in the elderly osteopenic spine including supplemental sublaminar wiring, increasing fixation points, cement augmentation of pedicle screws, cement kyphoplasty of adjacent uninstrumented vertebrae, hydroxyapatite-coated screws, and expandable screws. Instrumentation-related complications still remain a principal concern in the elderly, however. In a review of 47 deformity procedures in 38 patients over the age of 65, DeWald and Stanley20 reported a 13% early and 11% late instrumentation-related complication rate. Early complications included compression fractures of the most cephalic instrumented vertebrae as well as the superior adjacent body, and fractures of the pedicle. Late complications included loose or painful pedicle or iliac screws. Ten of 38 patients (26%) developed junctional kyphosis at the superior end of the construct, including late compression fractures.

Complications

Elderly patients who undergo surgery for spinal deformity are at a much greater risk for complications than adolescents and even younger adults.18,25,26 A wide range of complication rates have been reported, from 30% to 80%.

Outcomes

Because of improved medical screening, advanced surgical techniques, and specialized anesthesia training, patient-related outcomes following extensive reconstructive surgery for scoliosis in the elderly have dramatically improved from a generation ago. Li et al, 2 using SRS-22, SF-12, and ODI instruments, reported that adults over the age of 65 treated operatively had significantly less pain; better health-related quality of life, self-image, and mental health; and were overall more satisfied than age-related counterparts treated nonoperatively or simply observed. In fact, compared with younger age groups undergoing similar surgeries, it is the elderly who typically report similar, and in many cases, statistically superior improvements in pain and function, often because of extensive preoperative disability.3,7, 8 Radiographically, however, despite such significant functional and pain-related improvements, maintaining correction remains challenging in an age-dependent manner.

1. Glassman S.D., Alegre G.M. Adult spinal deformity in the osteoporotic spine: options and pitfalls. Instr. Course Lect.. 2003;52:579-588.

2. Li G., Passias P., Kozanek M., Fu E., Wang S., Xia Q., et al. Adult scoliosis in patients over sixty-five years of age: outcomes of operative versus nonoperative treatment at a minimum two-year follow-up. Spine. 2009;34(20):2165-2170.

3. Takahashi S., Delecrin J., Passuti N. Surgical treatment of idiopathic scoliosis in adults: an age-related analysis of outcome. Spine. 2002;27(16):1742-1748.

4. Deviren V., Berven S., Kleinstueck F., Antinnes J., Smith J.A., Hu S.S. Predictors of flexibility and pain patterns in thoracolumbar and lumbar idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2002;27(21):2346-2349.

5. Glassman S.D., Berven S., Bridwell K., Horton W., Dimar J.R. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine. 2005;30(6):682-688.

6. van Dam B.E., Bradford D.S., Lonstein J.E., Moe J.H., Ogilvie J.W., Winter R.B. Adult idiopathic scoliosis treated by posterior spinal fusion and Harrington instrumentation. Spine. 1987;12(1):32-36.

7. J.S. Smith, Risk-benefit assessment of surgery for adult scoliosis: an analysis based on patient age, Scoliosis Research Society 44th Annual Meeting and Course Final Program 2009:66–7, September, 2009.

8. B.A. O ’Shaughnessy, Is there a difference in outcome between patients under and over age 60 who have long fusions to the sacrum for the primary treatment of adult scoliosis, Scoliosis Research Society 44th Annual Meeting and Course: Final Program 2009:67–8, September, 2009.

9. Hu S.S., Berven S.H. Preparing the adult deformity patient for spinal surgery. Spine. 2006;31(19 Suppl):S126-S131.

10. Hammerberg E.M., Wood K.B. Sagittal profile of the elderly. J. Spinal Disord. Tech.. 2003;16(1):44-50.

11. Rose P.S., Lenke L.G., Bridwell K.H., Mulconrey D.S., Cronen G.A., Buchowski J.M., et al. Pedicle screw instrumentation for adult idiopathic scoliosis: an improvement over hook/hybrid fixation. Spine. 2009;34(8):852-857.

12. McPhee I.B., Swanson C.E. The surgical management of degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Posterior instrumentation alone versus two stage surgery,. Bull. Hosp. Jt. Dis.. 1998;57(1):16-22.

13. Bridwell K.H., Lenke L.G., McEnery K.W., Baldus C., Blanke K. Anterior fresh frozen structural allografts in the thoracic and lumbar spine. Do they work if combined with posterior fusion and instrumentation in adult patients with kyphosis or anterior column defects? Spine. 1995;20(12):1410-1418.

14. Kostuik J.P. Treatment of scoliosis in the adult thoracolumbar spine with special reference to fusion to the sacrum. Orthop. Clin. North Am.. 1988;19(2):371-381.

15. Halvorson T.L., Kelley L.A., Thomas K.A., Whitecloud T.S.3rd, Cook S.D. Effects of bone mineral density on pedicle screw fixation. Spine. 1994;19(21):2415-2420.

16. Eck K.R., Bridwell K.H., Ungacta F.F., Riew K.D., Lapp M.A., Lenke L.G., et al. Complications and results of long adult deformity fusions down to L4, L5, and the sacrum. Spine. 2001;26(9):E182-E192.

17. Devlin V.J., Boachie-Adjei O., Bradford D.S., Ogilvie J.W., Transfeldt E.E. Treatment of adult spinal deformity with fusion to the sacrum using CD instrumentation. J. Spinal Disord.. 1991;4(1):1-14.

18. Hu S.S.B., Sigurd H., Bradford D.S: Adult spinal deformity. In Frymoyer J.W., SWW. The adult and pediatric, third ed., spine, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 465-477, 2004.

19. Kostuik J.P.H., MH. Indications for surgery of the osteoporotic spine. In: Margulies J.Y., FY, Farcy J.C., Neuwirth M.G. Lumbosacral and spinopelvic fixation. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996.

20. DeWald C.J., Stanley T. Instrumentation-related complications of multilevel fusions for adult spinal deformity patients over age 65: surgical considerations and treatment options in patients with poor bone quality. Spine. 2006;31(Suppl. 19):S144-S151.

21. Jaovisidha S., Kim J.K., Sartoris D.J., Bosch E., Edelstein S., Barrett-Connor E., et al. Scoliosis in elderly and age-related bone loss: a population-based study. J. Clin. Densitom.. 1998;1(3):227-233.

22. Vanderpool D.W., James J.I., Wynne-Davies R. Scoliosis in the elderly. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 1969;51(3):446-455.

23. Healey J.H., Lane J.M: Structural scoliosis in osteoporotic women, Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res., 195:1985, 216-223.

24. Resnick D.N., G. Osteoporosis. In: bone and joint imaging. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1989.

25. Glassman S.D., Hamill C.L., Bridwell K.H., Schwab F.J., Dimar J.R., Lowe T.G. The impact of perioperative complications on clinical outcome in adult deformity surgery. Spine. 2007;32(24):2764-2770.

26. Faciszewski T., Winter R.B., Lonstein J.E., Denis F., Johnson L. The surgical and medical perioperative complications of anterior spinal fusion surgery in the thoracic and lumbar spine in adults. A review of 1223 procedures. Spine. 1995;20(14):1592-1599.