Chapter 3 Assessment

Introduction

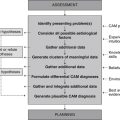

Competency in clinical assessment (in varying degrees) is an essential requirement of any practising healthcare professional, including practitioners of CAM. This is because assessment data directly inform clinical decision making, determining for instance when a clinician should initiate, continue or cease treatment, or when to refer or involve others in the multidisciplinary team. Even though the acquisition of pertinent knowledge and skills in clinical assessment is a vital first step to developing competence in this area, it is important to note that assessment is not just a step-by-step data collection exercise, but a process that requires a high level of critical thinking. Put simply, assessment should not be about ticking all the boxes, but about analysing and evaluating the data to determine what additional techniques and tests would support or refute suspected or possible diagnoses. This ongoing evaluation of the data is known as critical analysis, which is vital given that many client health problems can be complex and fraught with uncertainty. Integrating critical analysis into a comprehensive and systematic clinical assessment framework also promotes the efficient use of practitioner and client time, and healthcare resources. Before discussing such a framework, it is important to understand the types of data that can contribute to the clinical assessment.

Types of assessment data

There are several types of data that can be acquired during a clinical assessment. Each form can be distinguished by the means in which it is collected, interpreted and utilised. Recognising the merits and limitations of these different types of data is critical to understanding the assessment process. The first of these types is subjective data. This category of data is defined as that which is informed by personal opinion, feelings and perceptions. Subjective data are typically obtained during client and family interviews, and are the predominant form of data collected during a health history. While subjective data provide valuable information about a client’s lived experience, such as the duration and severity of a symptom, this form of data is easily confounded by personal bias, which raises concern about the accuracy and consistency of such information.1,2

The other major form of data that can be collected during the assessment process is objective data, which is defined as that which is observable, verifiable, measurable and not distorted by subjective impressions. Objective data are often acquired using recognised measures such as pathology tests, radiological imaging and physical examination techniques; as a result it is less likely to be tainted by personal bias. As such, the validity and reliability of objective data are greater than that obtained by subjective data. What this means is that clinicians should give higher priority to the collection of objective data over subjective information during the clinical assessment.3,4

CAM assessment process

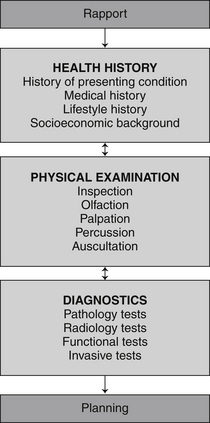

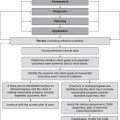

Clinical assessment is a pivotal component of DeFCAM in that it directly informs every succeeding stage of the process. For this reason it is necessary that client assessments are comprehensive and complete, and that they follow the principles of rigorous clinical assessment (see Table 3.1). One way practitioners can minimise the risk of omitting important data is to adopt a systematic approach to clinical assessment. The head to toe and body systems approaches are two such processes used in clinical practice. The problem with these methods is that neither presents a comprehensive approach to clinical assessment. The CAM assessment process is a more complete assessment process, not only because it integrates additional elements of the health history (such as socioeconomic background) and physical examination (such as olfaction), but also because it encompasses an essential diagnostics phase. These interrelated stages of the process and the non-linear nature of the approach are illustrated in Figure 3.1.

| Data should be | accurate |

| complete | |

| comprehensive | |

| interpreted appropriately | |

| corroborated by supporting evidence | |

| objective | |

| systematic | |

| Methods should be | ethically sound |

| reliable | |

| safe | |

| sensitive | |

| specific | |

| valid |

Health history

Implementing measures that build client rapport before and during the clinical consultation are critical to developing client trust, improving communication and enhancing the accuracy of acquired information.5 This is particularly important when completing a health history because subjective data often dominate this stage of assessment. It is probable that the quality of clinical assessments will be improved if clinicians become more consciously aware of the many factors that improve client rapport (see Table 2.1) and, more importantly, attempt to address these elements throughout the consultation.

Asking a clinician to speculate on the aetiology of a disease when the history of a presenting complaint is described as mild (severity), dull ache (quality) to the left lower abdominal quadrant (location) would be difficult and inappropriate. On the other hand, if the history added that the discomfort had been present for the past 3 months (onset), occurred intermittently every day (frequency) for approximately 1–2 hours at a time (duration), was non-radiating (radiation), improved by defecation (ameliorating factors), worsened by stress (aggravating factors) and was accompanied by bloating and flatus (concomitant symptoms), then a clinician may be able to consider possible hypotheses, such as irritable bowel syndrome. This description of the presenting complaint is summarised in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Core components of the presenting complaint description (ReLOAD FACQS)

| Re | Radiation |

| L | Location |

| O | Onset |

| A | Aggravating factors |

| D | Duration |

| F | Frequency |

| A | Ameliorating factors |

| C | Concomitant symptoms |

| Q | Quality |

| S | Severity |

Once the presenting condition has been adequately described the clinician can start to explore other factors that may contribute to the chief complaint, the client’s state of health and wellbeing, and the overall plan of care. These determinants can be separated into medical, lifestyle and socioeconomic factors. With reference to the medical determinants, these include family history of illness, allergies and sensitivities to foods, medications and environmental agents, over-the-counter and prescribed medications, complementary medicines and supplements, current and previous medical conditions or illnesses, and history of surgical or investigational procedures (see Table 3.3). For paediatric clients, it is important to also consider immunisation, birth, breastfeeding, growth and development history.

Table 3.3 Medical components of the health history (FAMMS)

| F | Family history |

| A | Allergies and sensitivities |

| M | Medications |

| M | Medical conditions |

| S | Surgical and investigational procedures |

Another important component of the health history is the client’s lifestyle history. A lifestyle history includes details about diet and fluid intake (including quality and quantity of consumed goods), illicit drug use (including type, route and frequency of use), smoking status (including strength and quantity), frequency and duration of exercise, alcohol use (including type, quantity and frequency), quality and duration of sleep, and entertainment and recreation choices (see Table 3.4).

Table 3.4 Lifestyle components of the health history (DISEASE)

| D | Diet and fluid intake |

| I | Illicit drug use |

| S | Smoking status |

| E | Exercise frequency and duration |

| A | Alcohol use |

| S | Sleep quality and duration |

| E | Entertainment or recreation choices |

The final part of the health history, socioeconomic background, is a particularly important component as many of the factors within this category are likely to affect a client’s capacity to understand and/or comply with treatment. This category includes information about the client’s family environment (including living arrangements, proximity of family, family dynamics), occupation and employment status, religion and cultural background, level of social support from family, friends and/or external agencies, level of educational attainment (including primary, secondary and tertiary level education), and residential and/or work environment (see Table 3.5). For paediatric clients, information also should be obtained about childcare arrangements and school performance.

Table 3.5 Socioeconomic components of the health history (FORSEE)

| F | Family environment |

| O | Occupation and employment status |

| R | Religion and cultural background |

| S | Social support |

| E | Education |

| E | Environment (work and residential) |

In an attempt to quantify the severity and/or impact of the presenting condition, some practitioners choose to use one of a number of clinical assessment tools, such as pain, depression, anxiety, stress and irritable bowel syndrome scales. Although such tools may be useful in providing clear, concise and measurable data about the presenting problem, which may help in the evaluation of client care, the validity and reliability of many evaluation tools are not well established. If the accuracy of a tool can be determined and the data are found to be reasonably consistent, then that assessment instrument may have a place in the CAM assessment process. Examples of tools that can be used in the assessment of conditions pertinent to each body system are outlined in the second half of this chapter.

Physical examination

A complete and comprehensive health history should provide the clinician with a detailed description of the client’s presenting condition and enable the practitioner to formulate a number of assumptions about the aetiology of the complaint. To determine which, if any, of these hypotheses are likely to become probable diagnoses, the clinician will need to test the assumptions by acquiring additional data. The source of such data can be derived from the physical examination (for a more detailed discussion of assumption or hypothesis processing, see chapter 4).

The physical examination generally involves some degree of physical contact between the practitioner and client, so it is critical that the clinician establishes some level of rapport and trust with the client (see chapter 2) and has at least obtained verbal consent from the client prior to commencing the examination. Appropriate hand washing, infection control measures, privacy, client conversation, instrument use, draping, level of client contact and exposure are also important measures for reducing a client’s risk of physical or psychological harm. Because inappropriate physical contact and professional misconduct are major causes of complaint against CAM practitioners,6–8 these strategies may also serve to protect clinicians from unnecessary professional and legal action. To further protect the client and practitioner from immediate and enduring harm, it is important that clinicians also recognise their professional boundaries and the limits to their scope of practice, and, where appropriate, refer clients to relevant health professionals for further assessment. For paediatric clients, it is important that a parent or guardian is present whenever possible.

Once these factors have been taken into consideration, a practitioner can commence the physical examination. The first part of this assessment, which begins from the time the practitioner makes visual contact with the client, is inspection. This visual assessment of the client incorporates a general and a specific component. The general inspection examines the client’s broad state of health by observing features such as posture, gait, affect, body language, physical guarding and functional capacity, which can alert the clinician to possible causes of the presenting condition as well as related comorbidities. Specific inspection focuses on the presenting complaint and associated body systems, and requires the clinician to make observations about pertinent structural and functional manifestations (including normal and atypical signs), such as a flat or distended abdomen and pink or pale skin colour.

The tactile component of the physical examination, known as palpation, uses deep and light touch, where relevant, to acquire information about the size, depth, texture, temperature, mobility, firmness and tenderness of the presenting condition.9 Apart from corroborating observed data, palpation adds necessary detail about the condition of the underlying structures, including muscles, bones, organs and blood vessels. The tactile examination of pulses, masses, lesions and areas of localised pain are some examples of where this technique maybe applied. Palpation also provides supporting evidence for pathological processes, such as inflammation, infection and carcinogenesis. A good case in point is erythema. The presence of localised erythema to the lower limb, for instance, says very little about the aetiology of the condition, but when combined with palpable heat and tenderness, suspicions of inflammation and/or infection may be confirmed.

Complementing palpation is percussion, an examination technique that uses touch (i.e. tapping the area of interest) and sound, specifically, vibration, to define the density of the underlying structure, in particular, whether the structure is gas, fluid or solid.10 This information can help a clinician distinguish between certain pathologies without relying on invasive or costly diagnostic tests in the early stages of assessment. A particularly important place for percussion is in the early detection of pneumonia, pneumothorax, internal bleeding and organomegaly. With reference to respiratory disease, percussion can be especially helpful in differentiating between generally less fatal conditions such as lobar pneumonia (manifested by percussive dullness), and life-threatening emergencies such as pneumothorax (manifested by hyper-resonance).

The data collected from a comprehensive health history and physical examination can be particularly helpful in informing the CAM practitioner about possible diagnoses, as well as the need for referral. The following example illustrates this point further. A brief clinical assessment that identifies the presence of cough and chest discomfort may mislead a practitioner into believing that a client has asthma or respiratory tract infection. A more detailed assessment that identifies the additional presence of haemoptysis, hoarseness, weight loss, dyspnoea, digital clubbing and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, may direct a practitioner to a more probable diagnosis of lung cancer, resulting in prompt referral to an allopathic medical practitioner and the avoidance of unnecessary delays in treatment. Other clinical manifestations that should alert a clinician to the possibility of more serious pathology, and the need for prompt referral to an appropriate practitioner, are bleeding (such as haemoptysis, melaena and haematuria), escalating pain (including central chest pain, cephalgia and abdominal pain), altered levels of consciousness, seizures, unresolving masses, rapid weight loss and petechiae.

Diagnostics

Investigations not typically performed by CAM practitioners, but for which clinicians may need to interpret findings or refer clients on, are invasive procedures. These investigations, often used in conjunction with pathology tests, provide important information about the structure, function and/or pathology of the presenting complaint, although when compared with other diagnostic methods, most invasive tests pose a greater risk of harm to the client, including an increased risk of pain, infection and haemorrhage.

The other category of diagnostic investigation, which is commonly used by CAM practitioners, is the miscellaneous tests. Despite the long history of use of these tests within CAM, particularly methods such as iridology, kinesiology, Vega testing and pulse diagnosis, there is insufficient clinical evidence to support their use. This is not to say that these methods are ineffective or should be dismissed in clinical practice, only that further research is needed to evaluate the validity and reliability of these procedures. Miscellaneous tests are not confined to CAM diagnostics: this category also captures investigations that do not nest within the other four diagnostic categories, including electrodiagnostics and sleep studies. Examples of tests that fall into the five diagnostic categories are listed in Table 3.6.

Table 3.6 Examples of diagnostic tests that may be requested, performed or interpreted in CAM practice

| Pathology tests | Carbohydrate breath test |

| Complete blood examination (CBE) | |

| Culture and sensitivity testing (C&S) | |

| Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) | |

| Lipid studies | |

| Liver function test (LFT) | |

| Nutrient levels (iron studies, hair mineral analysis) | |

| Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) | |

| Semen analysis | |

| Thyroid function test (TFT) | |

| Urinalysis (UA) | |

| Functional tests | Adrenal hormone profile |

| Bone metabolism assessment | |

| Comprehensive detoxification profile (CDP) | |

| Comprehensive digestive stool analysis (CDSA) | |

| Intestinal permeability (IP) test | |

| Pulmonary function test (PFT) | |

| Urodynamic studies | |

| Radiological tests | Computed tomography scan (CT) |

| Contrast studies | |

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | |

| Mammography | |

| Positron emission tomography (PET) | |

| Radiograph/X-ray | |

| Ultrasound (US) | |

| Invasive tests | Allergy skin testing (prick-puncture test) |

| Arthroscopy | |

| Biopsy | |

| Colonoscopy | |

| Endoscopy | |

| Laparoscopy | |

| Lumbar puncture (LP) | |

| Miscellaneous tests | Electrodiagnostics (electrocardiograph) |

| Iridology | |

| Plethysmography | |

| Pulse diagnosis | |

| Quantitative sensory testing (QST) | |

| Sleep studies |

Cardiovascular system assessment

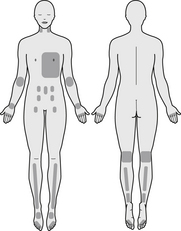

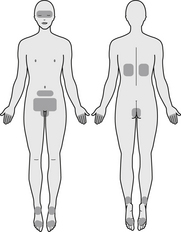

These points should be taken into account when conducting a comprehensive assessment of the cardiovascular system. An outline of the regions pertinent to cardiovascular system assessment is illustrated in Figure 3.2.

Health history

History of presenting condition

Identify the client’s primary problem and establish the location, onset, duration, frequency, quality and severity of the sign or symptom, the presence of radiating symptoms (e.g. chest pain radiating down the left arm or up the neck may indicate myocardial ischaemia), any aggravating or ameliorating factors (such as walking, stress, rest or leg elevation) and any concomitant symptoms (including shortness of breath, fatigue, chest pain, palpitations, claudication, paresthesias and syncope).

Lifestyle history

Identify any factors that may increase the client’s risk of CVD, such as obesity, tobacco use (including number and strength of cigarettes inhaled in a day), alcohol consumption (including number of standard drinks and type of alcoholic beverage consumed in a day), illicit drug use (including type, route and quantity of drug used per day), diet and fluid intake (such as sodium, omega 3 fatty acids, saturated fat, fibre, fruit and vegetable consumption), quality and duration of sleep (e.g. broken sleep, sleep apnoea) and frequency and duration of exercise.11

Physical examination

Inspection

Observe for any signs of impaired cardiovascular function, such as xanthomata (hard, yellow masses that are pathognomonic of familial hypercholesterolaemia),10 digital clubbing (an abnormal enlargement of the terminal phalanges that may be a sign of chronic hypoxia), splinter haemorrhages of the nail bed (present in infective endocarditis12), dyspnoea, pallor or cyanosis (may be observed in hypoxia, anaemia, vasoconstriction or vascular occlusion), Lichstein’s sign (oblique, bilateral earlobe crease observed in people over 50 years of age with significant coronary heart disease),12 dependent oedema (may be indicative of chronic venous insufficiency or right-sided heart failure), leg ulceration (may be indicative of peripheral vascular disease) and lower leg varicose veins and ochre pigmentation (both signs suggest the presence of chronic venous insufficiency). The presence of chest scars (from sternotomy or pacemaker insertion) and/or deformities (such as pectus excavatum or pectus carinatum) may also draw attention to the possibility of cardiovascular defects.

Palpation

Examine major pulses of the neck (carotid), chest (cardiac apex), upper limbs (brachial, radial, ulnar) and lower extremities (femoral, popliteal, posterior tibial, dorsalis pedis) and note the rate, rhythm and amplitude of each pulse, as well as the presence of any thrills or palpable vibratory sensations (thrills are indicative of turbulent blood flow). Assess the peripheries for temperature (cool hands and feet may be indicative of cardiac failure or peripheral vascular disease) and pitting oedema (may indicate the presence of chronic venous insufficiency or right-sided heart failure). In terms of cardiac function, identify the position and diameter of the point of maximum impulse (PMI) (a laterally displaced or enlarged PMI is suggestive of cardiomegaly)10 and the presence of thrills or increased pulse intensity over the aortic area (may suggest the presence of aortic dilatation), pulmonic area (may be indicative of pulmonary artery dilatation), mitral area (may be indicative of mitral stenosis or regurgitation) and tricuspid area (may be a sign of tricuspid stenosis or regurgitation).

Clinical assessment tools

Aberdeen varicose vein questionnaire (AVVQ)

Measures health-related quality of life in clients with varicose veins.

MacNew heart disease health-related quality of life questionnaire

Assesses the effect of coronary heart disease and its treatment on physical, emotional and social functioning, and on activities of daily living.

Diagnostics

Pathology tests

Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA)

ADMA is a by-product of protein methylation. Elevated levels of ADMA are associated with smooth muscle cell proliferation and platelet aggregation. ADMA is also an endogenous inhibitor of nitrous oxide; elevated levels are linked to endothelial dysfunction and small vessel disease.14

C-reactive protein (CRP)

CRP is a marker of inflammatory activity, which is implicated in the development and complications of atherosclerosis.15 CRP is independently related to future cardiovascular events.15

Cardiac enzymes/proteins

These are released from the myocardium during injury, such as in myocardial infarction. Because many of these enzymes or proteins are also present in skeletal tissue, it is recommended that cardiac-specific enzymes or proteins be ordered, including cardiac-specific troponin T and I, and the isoenzyme creatine phosphokinase-MB.16

Hair, urine, serum and blood nutrient levels

These tests may be indicated when presenting clinical manifestations are suggestive of nutrient deficiency or toxicity, when the presenting condition is likely to be caused by nutrient deficiency or toxicity or when the condition is likely to contribute to the development of nutrient deficiency or toxicity. Nutrient tests that are particularly relevant to cardiovascular assessment are hair mineral analysis, serum vitamin B12, serum magnesium, serum coenzyme Q10, serum zinc, red blood cell folate and iron studies.

Homocysteine (Hcy)

Hcy is an amino acid derived from methionine. Even though Hcy plays an important role in protein synthesis, elevated levels are associated with smooth muscle cell proliferation, platelet aggregation and impaired endothelial derived nitric oxide induced vasodilatation, all of which promote atherosclerosis.17,18

Lipid studies

High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C)

HDL-C is a class of lipoprotein that transports cholesterol from the tissues and circulation to the liver. Increased levels of serum HDL-C are inversely related to the development of atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease.15

Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C)

LDL-C is a class of lipoprotein that transports cholesterol from the liver to the peripheral tissues. Elevated levels of serum LDL-C are positively correlated with the incidence of cardiovascular disease.15

Radiology tests

Angiography/venography

This is an invasive radiological procedure in which a blood vessel is injected with contrast media and a series of X-ray images taken. By assessing blood flow dynamics and blood vessel defects, this procedure can support suspicions of aneurysm, vessel stenosis or occlusion, and vascular malformation.16

Computed tomography (CT)

CT uses multiple X-ray beams to produce cross-sectional images of the head, chest, abdomen and pelvis to provide information about cardiovascular structure. CT imaging is particularly useful for identifying aneurysms, vessel occlusion or stenosis (with angiography), arteriovenous malformations, haematomas and haemorrhage.20

Doppler/ultrasound

This test uses sound waves to assess blood flow velocity and direction, and blood flow disturbances of major blood vessels, including the carotid arteries and the arteries and veins of the extremities. It is a procedure that is useful for detecting aneurysms, vessel occlusion or stenosis, deep vein thrombosis, Raynaud’s disease, chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins.18

Echocardiography

Echocardiography uses ultrasonic waves to evaluate cardiac structure and function, including information about heart size, position, walls, valves and chambers, the pericardium and masses. This procedure can help in the diagnosis of valvular regurgitation or stenosis, thrombus formation, endocarditis, myxoma, septal or congenital heart defects, cardiomyopathy and ventricular hypertrophy.18

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI uses magnetic and radiofrequency energy to produce images of the heart and vasculature, including information on structure and function. MRI is particularly useful for detecting aneurysms, congenital heart defects, myocardial infarction/ischaemia, pericardial changes, vascular malformations and arterial occlusive disease, and for determining cardiac chamber and ventricular function.18

Positron emission tomography (PET)

PET provides anatomical and functional information about the heart. Following the administration of an inhaled or intravenous radionuclide, areas of radionuclide accumulation, which reflect the level of cellular metabolic activity, are tracked by CT imaging and positron detectors. A reduction in positron emission, and thus cardiac metabolism, can occur in conditions such as myocardial infarction or scarring.16 Increased cellular metabolism may be a sign of carcinoma. Other abnormal states that may be detected by PET include heart chamber disorders and ventricular enlargement.18

X-rays or radiographs

X-rays use electromagnetic radiation to produce images of the heart (providing information about size, shape and location), pericardium (particularly the presence of inflammation or effusion), large blood vessels (such as the aorta) and, in conjunction with angiography, smaller blood vessels. Without contrast media, X-rays are limited to detecting cardiac enlargement, pericarditis, pericardial effusion and large vessel dilatation or stenosis.20

Invasive tests

Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE)

TOE assesses the size, position, chambers, valves and movements of the heart, as well as the condition of proximal blood vessels. This procedure is useful for detecting coronary artery disease, congenital heart defects, aneurysms, valve and septal defects, thrombi and congestive cardiac failure.18

Miscellaneous tests

Arterial/venous plethysmography

This procedure measures volume changes in the blood vessels of the upper and lower extremities to determine the presence of occlusive disease such as venous thrombosis, arterial embolisation and Raynaud’s disease.18

Electrocardiograph (ECG)

An ECG measures the electrical activity of the heart. The reading can be used to detect cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial ischaemia, electrolyte imbalances, conduction defects, pericarditis, cor pulmonale and ventricular hypertrophy.16

Exercise stress test

An exercise stress test assesses the response of the heart and the vessels of the lower limb to physical stress. The results can be used to identify the presence of intermittent claudication, occlusive coronary artery disease, exercise-induced hypertension and cardiac dysrhythmias.16

Iridology

Iridology can be used to detect the presence of arcus senilis (a whitish ring at the perimeter of the cornea), which is highly suspicious of hypercholesterolaemia in clients under 40 years of age.10 The sign is also predictive of CVD and coronary artery disease in older people, yet, given that arcus senilis is strongly associated with increasing age, the sign may be misleading in this population.21

Respiratory system assessment

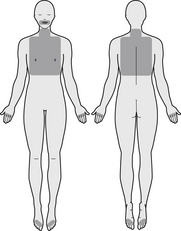

A practitioner should consider these points when conducting a comprehensive assessment of the respiratory system. An outline of the regions pertinent to respiratory system assessment is illustrated in Figure 3.3.

Health history

History of presenting condition

The practitioner should ascertain the client’s primary problem and determine the location, onset, duration, frequency, quality and severity of the sign or symptom, the presence of radiating symptoms, any aggravating or ameliorating factors (such as exercise, cold air, cigarette smoke, dietary factors or medication) and any concomitant symptoms (including fatigue, dyspnoea, dyspepsia, pain, cough, nasal discharge, haemoptysis, fever and hoarseness).

Medical history

Lifestyle history

Identify any lifestyle determinants that may exacerbate, prolong or increase a client’s risk of upper or lower respiratory tract illness, particularly tobacco use (including number and strength of cigarettes inhaled in a day) and level of physical activity,22 and diet and fluid intake (i.e. sodium, tea, fruit and vegetable consumption).23

Socioeconomic background

Ascertain if there are any socioeconomic factors that may increase the client’s risk of respiratory disease, affect their understanding of the condition or the management of the disease, such as residential and/or work environment (i.e. whether the client resides near an industry or arterial road, whether they are exposed to dust, asbestos, silica, chemicals or other respiratory irritants or whether any people in the household smoke), family environment (i.e. marital status, number and ages of children), occupation and employment status (i.e. day or nightshift, full or part time, number of jobs), religion, ethnicity, race or cultural background (i.e. whether the client follows strict dietary practices, whether the client’s culture, race or ethnic background place the client at increased risk of developing respiratory disease), level of social support (i.e. whether the client lives alone or receives community services) and level of educational attainment (i.e. primary, secondary and/or tertiary education).

Physical examination

Inspection

Assess the quality of respirations, taking particular note of the rate (an accelerated respiratory rate may be a sign of anxiety, fever, metabolic acidosis or airway obstruction; bradypnoea may signify liver failure, diabetic ketoacidosis or increased intracranial pressure), rhythm (an irregular breathing pattern, such as Cheyne-Stokes or Biot’s breathing, may suggest brain damage or drug-induced respiratory depression),10 depth (hyperpnoea, or deep breathing, may occur in metabolic acidosis; shallow breathing can be a sign of pneumonia, pulmonary oedema, COPD or pleurisy) and effort of respirations (laboured breathing may occur in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). The clinician should also observe for signs of clubbing (an abnormal enlargement of the terminal phalanges that may be indicative of chronic hypoxia), central cyanosis (a bluish tinge to the lips and tongue that may signify reduced arterial oxygenation, which can occur in severe airflow limitation or pulmonary fibrosis),12 finger or fingernail staining (brown-yellow staining of the fingers can indicate a history of cigarette smoking), nasal flaring, accessory muscle use and intercostal retraction (these signs are indicative of airway obstruction and/or respiratory distress), tracheal asymmetry (tracheal deviation may occur in upper lobe lung disease, such as tension pneumothorax),24 chest wall asymmetry (asymmetrical movement of the chest may signify impaired air entry from localised pulmonary consolidation, collapse, fibrosis or effusion)24 and chest wall deformities (pectus carinatum may develop following severe respiratory illness in childhood; barrel chest may occur in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).12 Other noteworthy observations that may allude to previous respiratory dysfunction include body position (whether the client finds it difficult to breathe when lying down on the examination table), flow of conversation (whether the client can maintain a normal conversation without becoming short of breath), pharyngeal mucosa (whether there is pharyngeal erythema or tonsillar enlargement), scarring (whether there is evidence of previous thoracic surgery (i.e. thoracoplasty) and trauma (whether there are chest drain scars from previous pneumothorax or haemothorax). For paediatric clients, the practitioner should also observe for the presence of foreign bodies in the ear, nose and throat.

Olfaction

During the clinical examination, the clinician should note the presence of halitosis, or foul-smelling breath. This symptom may allude to the existence of dental, gingival, sinus, oral, oesophageal or respiratory pathology. In terms of the latter, this can include respiratory tract infection, lung abscesses and bronchiectasis.

Palpation

Palpate the paranasal sinuses (localised tenderness may indicate sinusitis), the position of the trachea (tracheal deviation may suggest a mediastinal shift), the presence of chest wall masses, sinus tracts and discomfort (chest/intercostal tenderness may be associated with pleurisy and/or underlying musculoskeletal disease; sinus tracts may indicate tuberculosis or actinomycosis),9 and the size, shape, mobility and tenderness of lymph nodes (tender and mobile lymph nodes are suggestive of infection and/or inflammation).9 The degree of symmetry of respiratory expansion is another important technique that can aid the detection of localised pulmonary disease, such as pneumonia or bronchial obstruction. The density of underlying tissue can be determined by palpating the chest wall for tactile fremitus (vibrations transmitted from voice sounds to the chest wall may be reduced in the presence of liquid, gas and excess adipose tissue, and increased in solid or consolidated areas).10

Percussion

Much like tactile fremitus, percussion is also used to assess the density of underlying tissues up to a depth of 5–7 centimetres. Percussion can help to confirm or refute any abnormal findings identified during palpation. Percussive tones that may be detected include flatness (short, high pitch tone over a fluid-filled region, such as pleural effusion), dullness (medium duration and medium pitch tone over a solid area, such as pneumonia), resonance (long, low pitch tone over normal lung) and hyperresonance (long, low pitch tone over an air-filled structure, such as pneumothorax).24

Auscultation

The auscultation of breath sounds is an important component of the respiratory assessment as it provides valuable information about airflow. Using the diaphragm of a stethoscope, examine the quality, location, intensity and duration of breath sounds, including the presence of vesicular breath sounds (soft, low pitch breath sounds normally heard over most parts of the lungs) and bronchial breath sounds (the presence of these loud, high-pitch sounds over areas other than the manubrium may indicate lung consolidation).24 Additional cues about underlying pathology can be determined from adventitious sounds such as stridor (due to narrowing or obstruction of the larynx or trachea), crackles (from excess airway secretions, as in respiratory tract infection and pulmonary oedema), wheezes (resulting from narrowed or obstructed airways), rhonchi (from transient airway plugging, as in bronchitis) and pleural rub (due to pleural inflammation).10 Auscultation also can be used to assess the density of underlying tissue by examining the quality of transmitted voice sounds. The existence of bronchophony (when the spoken words ‘ninety-nine’ become loud and clear), aegophony (when the spoken sound ‘ee’ sounds like ‘ay’) and/or whispered pectoriloquy (when the whispered words ‘ninety-nine’ become loud and clear) over any part of the chest is suggestive of lung consolidation.9

Clinical assessment tools

Cystic fibrosis questionnaire (CFQ)

Measures the effect of cystic fibrosis on overall health, activities of daily living and wellbeing.

Diagnostics

Pathology tests

Arterial blood gases (ABG)

Hair, urine, serum and blood nutrient levels

These nutrient tests may be indicated when presenting clinical manifestations are suggestive of nutrient deficiency or toxicity, when the presenting condition is likely to be caused by nutrient deficiency or toxicity or when the condition is likely to contribute to the development of nutrient deficiency or toxicity. Nutrient tests that are particularly relevant to respiratory assessment are hair mineral analysis, serum vitamin A, serum pyridoxine and serum calcium.

Sputum culture and sensitivity testing

Testing of a fresh sputum specimen enables sufficient numbers of the organism to be isolated, identified and quantified, and the antibiotics to which the microbial strains are sensitive or resistant to be determined. This test may be ordered for the purpose of aiding the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial, viral or fungal infection of the respiratory tract.16

Radiology tests

Chest X-ray (CXR)

CXR uses electromagnetic radiation to produce images of the chest wall, lung fields, bones and diaphragm; it can also be used to detect abscesses, atelectasis, bronchitis, COPD, lymphadenopathy, tumours, pleural effusion, pleuritis, pneumonia, pulmonary oedema, haemo/pneumothorax, pulmonary fibrosis and tuberculosis.20

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI uses magnetic and radiofrequency energy to generate images of the lungs, pleural space, soft tissues and bones, and together with appropriate agents, can also assess lung perfusion and ventilation. While MRI can be used to detect pleural effusion, tumours, lung malformations, pneumonia, asbestosis and lung fibrosis, motion artefacts are a current concern with chest MRI.25

Ventilation–perfusion (VQ) scan

A VQ scan uses intravenous radioactive material to assess pulmonary blood flow and perfusion, and an aerosolised agent (such as Krypton gas) to measure the patency of pulmonary airways. A VQ mismatch (i.e. normal ventilation and abnormal perfusion) is indicative of pulmonary embolus, whereas abnormal ventilation and perfusion findings are suggestive of pneumonia, emphysema and/or pleural effusion.16

Functional tests

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs)

PFTs are often performed to evaluate the presence and severity of respiratory disease. The PFT can incorporate any number of different measures of lung volume and capacity, including total lung capacity, tidal volume, forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), maximal mid-expiratory flow (MMEF), maximal volume ventilation (MVV), peak inspiratory flow rate (PIFR) and peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). Reductions in many of these measures are often evident in asthma, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis and other obstructive pulmonary diseases.16

Invasive tests

Bronchoscopy

This is an endoscopic procedure that enables direct visualisation of the trachea, larynx, bronchi, bronchioles and alveoli. As a diagnostic tool, bronchoscopy is useful in detecting tumours, inflammatory disease, foreign bodies, structural anomalies, abscesses, interstitial pulmonary disease, strictures, tuberculosis and opportunistic lung infections. Bronchoscopy also plays an important role in the collection of tissue biopsies.20

Thoracentesis, or pleural tap

In this procedure, a needle is inserted into the pleural cavity for the purpose of removing fluid or gas. As a diagnostic tool, thoracentesis is used to determine the aetiology of a pleural effusion such as empyema, pneumonia, tuberculosis, pulmonary infarction, malignancy and haemothorax.16

Gastrointestinal system assessment

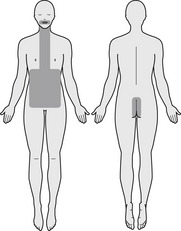

Any deviation from normal GI integrity or physiology may manifest as abnormal changes in these functions. These points should be taken into consideration when conducting a comprehensive assessment of the gastrointestinal system. An outline of the regions pertinent to gastrointestinal system assessment is illustrated in Figure 3.4.

Health history

History of presenting condition

After establishing the client’s primary problem, ascertain the location, duration, frequency, onset, quality and severity of the sign or symptom, the presence of radiating symptoms (i.e. right upper quadrant pain radiating to the right inferior scapula is suggestive of cholelithiasis),26 any aggravating or ameliorating factors (such as emotional stress, alcohol, dietary components, exercise, defecation, meal consumption, cigarette smoking, distinct odours, medications or movement) and any concomitant symptoms (including fatigue, fever, diarrhoea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, odynophagia, halitosis, weight change, pain, flatulence, bloating, dysphagia, tenesmus, dyspepsia, anorexia, abdominal distension and cramping).

Medical history

Lifestyle history

Identify any factors that may increase the client’s risk of GI illness or exacerbate the presenting complaint, such as tobacco use (including number and strength of cigarettes inhaled in a day),27 alcohol consumption (including number of standard drinks and type of alcoholic beverage consumed in a day),28 illicit drug use (including type, route and quantity of drug used per day), diet and fluid intake (such as fibre, fruit and vegetable consumption, dairy and wheat intake),26,29 quality and duration of sleep (e.g. broken sleep, sleep apnoea),30 and frequency, duration and type of exercise.31

Physical examination

Inspection

Observe for any signs of previous or existing impairment to GI structure and/or function, beginning with examination of the oral cavity, including the lips (i.e. angular stomatitis), tongue (i.e. candidiasis, carcinoma, glossitis), palate (i.e. torus palatinus), gingivae (i.e. gingivitis, ulceration, bleeding), teeth (i.e. caries) and oropharynx (i.e. tonsillitis, pharyngitis). This examination is particularly important as these structures play an essential role in chemical and mechanical digestion, and furthermore, can manifest early signs of nutritional imbalance and/or deficiency. Inspection of the skin and sclera may also detect the presence of jaundice that may be secondary to haemolysis or liver disease.24 For paediatric clients, the buccal mucosa should be assessed for the presence of Koplik’s spots (small white spots indicative of measles), the soft palate should be inspected for Forschheimer’s spots (small dusky red spots that may arise at the onset of rubella), and the number and condition of the teeth recorded.10

The abdomen should then be observed for scars (from previous surgery or trauma), striae (such as the pink purple striae of Cushing’s syndrome), dilated veins and/or spider naevi (due to liver disease), everted umbilicus (due to late pregnancy, ascites or large mass), ecchymosis (bluish discolouration of the flanks and/or periumbilicus secondary to haemoperitoneum), rashes, peristalsis (visible peristalsis may indicate intestinal obstruction), lesions, asymmetry (due to organomegaly or masses), contour and herniation.9 Where appropriate, the anus and perianal region should be inspected for signs of underlying pathology, such as haemorrhoids (may be indicative of constipation), lichenification (suggestive of pinworm infection), excoriation (a manifestation of chronic diarrhoea) and fistula formation (a sign of IBD). Because of the potential risk of litigation with this technique, this aspect of the examination should be restricted to clinicians who are qualified to perform this assessment.

Olfaction

The presence of abnormal odours from the GI tract may highlight signs of underlying pathology. Fetid smelling stools, for instance, may suggest the presence of malabsorption syndrome, steatorrhoea, cystic fibrosis, coeliac disease, intestinal dysbiosis or GI infection. Halitosis may be indicative of tobacco use, poor oral hygiene, dental disease, mouth ulceration, liver disease, dry mouth, carcinoma, GORD, bowel obstruction or infection.24

Palpation

Light and deep palpation is used to assess the position, shape, mobility, consistency, tenderness and size of the liver, spleen and abdominal contents, as well as any masses.9 Particularly useful signs of underlying pathology are Murphy’s sign (the existence of right upper quadrant pain subsequent to right subchondral pressure and deep inspiration, which is suggestive of cholecystitis), Rovsing’s sign (the occurrence of right lower quadrant pain following the application of left lower quadrant pressure, which is a sign of appendicitis) and rebound tenderness (the presence of abdominal pain following the rapid withdrawal of deep pressure, which may be indicative of peritoneal irritation). The presence of voluntary guarding and/or involuntary muscle spasm or rigidity is also suggestive of an irritated peritoneum.10 Qualified clinicians may choose to perform a rectal examination to detect the presence of haemorrhoids, rectal prolapse, fissures, fistulas and carcinoma of the anus.24

Percussion

This technique can be applied to assess the size and location of masses and organs (which produce a dull percussive tone), and fluid or air-filled regions (which produce a tympanic percussive tone).9

Auscultation

The pitch and frequency of bowel sounds can allude to changes in GI function. Hyperactive bowel sounds, for instance, may be suggestive of diarrhoea or early intestinal obstruction, whereas hypoactive or absent bowel sounds may indicate peritonitis and paralytic ileus.24

Clinical assessment tools

Cystic fibrosis questionnaire (CFQ)

CFQ measures the effect of cystic fibrosis on overall health, activities of daily living and wellbeing.

Diagnostics

Pathology tests

Amylase

Amylase is an enzyme located within the pancreatic acinar cells. Trauma, pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma and/or pancreatic cysts can cause damage to these cells, resulting in excess amounts of this enzyme entering the circulation.32

Carbohydrate breath test

Assesses carbohydrate malabsorption, orocecal transit time and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). The test requires the client to consume a specified dose of carbohydrate (lactulose, lactose, fructose, glucose), which the intestinal bacteria metabolise into hydrogen and/or methane. After ingestion, a series of breath samples is taken over a 2–4 hour period. The increased presence of exhaled hydrogen and/or methane (typically over 20 parts per million) is suggestive of carbohydrate malabsorption and possibly SIBO. The sensitivity and specificity of this test for SIBO is currently inadequate for routine clinical use.33

Helicobacter pylori breath test or urea breath test

A highly specific and sensitive test for detecting H. pylori infection as a cause of peptic ulceration, gastric carcinoma and gastritis that requires the oral administration of radiolabelled carbon and urea, which, in the presence of H. pylori, is converted into CO2. The radiolabelled CO2 is exhaled after 30 minutes, collected and tested.26

Culture and sensitivity testing

This type of testing of a fresh stool specimen enables sufficient numbers of an organism to be isolated, identified and quantified, and the antibiotics that the microbial strains are sensitive or resistant to, to be determined. This test may be ordered to aid the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial, viral, fungal, protozoan or parasitic enterocolitis.16

Faecal analysis

This test examines a number of stool characteristics, including appearance, colour, occult blood (present in carcinoma, inflammatory bowel disease, upper GI disease and diverticular disease), epithelial cells (elevated in IBD), leucocytes (increased in intestinal infections), carbohydrates (present in malabsorption syndromes), fat (a sign of fat malabsorption), meat fibres (present in altered protein digestion) and trypsin (reduced in malabsorption syndromes, cystic fibrosis and pancreatic deficiency).18

Liver function test (LFT)

A LFT provides information about liver function (i.e. total protein, albumin, bilirubin, ammonia) and hepatocyte integrity (i.e. alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), alanine amino transferase (ALT), aspartate amino transferase (AST)). Results of the LFT can assist in the diagnosis of alcohol abuse, cirrhosis, hepatitis, liver disease, biliary disease, malnutrition and malabsorption.34

Radiology tests

Abdominal X-ray

Uses electromagnetic radiation to generate images of the abdominal cavity and organs, which can detect conditions such as hepatomegaly, bowel obstruction, abscesses, perforation, paralytic ileus and tumours.20

Computed tomography (CT)

CT uses multiple X-ray beams to generate cross-sectional images of the abdomen and pelvis, thus enabling the detection of tumours, cysts, bowel obstruction, bleeding, pancreatitis, cirrhosis, fatty liver, diverticulitis, colonic polyps, cholelithiasis and ductal obstruction or dilatation.18

Lower GI series, or barium enema

Provides serial X-ray images of the colon and distal ileum using rectally administered barium contrast media to enhance visualisation. A lower GI series can be ordered to facilitate a diagnosis of carcinoma, IBD, polyps, diverticula, structural defects, perforation, fistula formation, appendicitis and herniation.16

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI uses magnetic and radiofrequency energy to produce images of the organs and soft tissues of the abdomen and pelvis that can be useful in detecting tumours, pancreatitis, cholangitis, peritonitis, abscesses, cirrhosis, fatty liver, diverticulitis, cholelithiasis and ductal obstructions or dilatation.18

Ultrasound

Ultrasound uses sound waves to assess the size, position, contour and texture of the organs of the abdomen and pelvis in order to detect conditions such as pancreatitis, ductal obstructions or dilatation, cysts, tumours, cirrhosis, cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, hepatitis and peritonitis.18

Upper GI series, or barium swallow

Provides serial X-rays of the lower abdomen, stomach and duodenum using orally administered barium contrast media to enhance visualisation. This test is particularly useful for detecting tumours, oesophageal varices, hiatus hernia, perforation, strictures, congenital defects, peptic ulceration, motility disorders and diverticula.20

Functional tests

Comprehensive detoxification profile, or functional liver detoxification profile

Measures the rate of phase I and phase II liver detoxification following caffeine, aspirin and paracetamol challenge. Findings from this test, such as a reduction in the rate of substance clearance, can provide important insight into a client’s liver function, specifically, whether a client is able to effectively clear toxic metabolites from the blood.35

Comprehensive digestive stool analysis (CDSA)

CDSA obtains data on enzymatic digestion, fatty acid absorption, microbiological balance and metabolic markers of disease, and may help to determine the presence of intestinal dysbiosis, intestinal candidiasis, nutrient malabsorption and indigestion.36

Intestinal permeability test

This test assesses small intestine absorption and permeability by measuring urinary elimination of lactulose and mannitol 6 hours after oral administration. Increased elimination of these non-metabolised sugars in the urine may be indicative of leaky gut syndrome and impaired intestinal permeability, whereas reduced urinary elimination may suggest malabsorption.37

Invasive tests

Abdominal paracentesis, or peritoneal tap

Requires the insertion of a sterile needle into the peritoneal cavity for the purpose of removing fluid. As a diagnostic tool, the procedure is used to determine the aetiology of peritoneal effusion, such as carcinoma, peritonitis, pancreatitis, tuberculosis, lymphoma and perforation.16

Biopsy

A biopsy involves the excision of a small sample of tissue and the subsequent microscopic examination of the sample in order to identify cell morphology and tissue abnormalities. A biopsy of GI tissue may assist in the diagnosis of cancer, infection, inflammation, cirrhosis, coeliac disease and lactose deficiency.18

Colonoscopy

Permits direct visualisation of the colon, ileocecal valve and terminal ileum through the use of a flexible fiberoptic colonoscope. Colonoscopy can be used to determine the presence of tumours, polyps, inflammation, diverticula, haemorrhoids, ulceration and bleeding.20

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

ERCP enables direct and radiographic visualisation of the biliary and pancreatic ducts through the use of a fiberoptic endoscope, X-ray imaging and contrast media. As a diagnostic procedure, ERCP can identify the presence of obstructive jaundice, duodenal papilla carcinoma, pancreatitis and pancreatic or biliary duct abnormalities, calculi, stenosis or cysts.16

Gastric acid stimulation test

Measures the volume and pH of gastric acid before and after administration of a gastric acid stimulant, such as pentagastrin. Nasogastric aspirates of stomach acid are analysed to determine the cause of peptic ulceration, pernicious anaemia or gastrinoma, the efficacy of ulcer treatment and the presence of hyper- or hypochlorhydria.18

Laparoscopy

Through the use of a rigid fibreoptic laparoscope, enables direct visualisation of the peritoneal cavity and abdominal organs, including the stomach, liver, gallbladder, pancreas and intestines. The procedure is helpful in detecting tumours, adhesions, cirrhosis, lymphomas, perforation, inflammation and infection.20

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD)

OGD uses a fibreoptic endoscope to examine the upper GI tract, including the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum. Capsule endoscopy, which uses an orally administered capsule camera, is also capable of visualising the jejunum and ileum. Both endoscopic procedures are useful in detecting oesophageal varices, diverticula, duodenitis, oesophagitis, gastritis, hiatus hernia, peptic ulceration, tumours, bleeding, stenosis and polyps.18

Urinary system assessment

These considerations should be borne in mind when conducting a comprehensive assessment of the urinary system. An outline of the regions pertinent to urinary system assessment is illustrated in Figure 3.5.

Health history

History of presenting condition

Identify the client’s primary problem and establish the quality, severity, onset, location, duration and frequency of the sign or symptom, the presence of radiating symptoms (i.e. pain radiating from the flank, across the abdomen and down the inner thigh is suggestive of urinary calculi),26 any aggravating or ameliorating factors (such as fluid consumption, constipation, body position, cigarette smoking, spices, alcohol or caffeine) and any concomitant symptoms (including urinary frequency, urgency, tenesmus, dysuria, nocturia, enuresis, haematuria, hesitancy, dribbling, incontinence, loin pain, pneumaturia, polyuria, pyrexia, oliguria, oedema, and any changes in urine colour, odour, turbidity, force and calibre of stream).

Medical history

Family history

Medical conditions

Establish if there are any current or previous medical conditions that involve the kidney, bladder or urinary tract, such as cancer, cystitis, benign prostatic hypertrophy, hydronephrosis, glomerulonephritis, nephritic/nephrotic syndrome, nephropathy, polycystic kidney disease, pyelonephritis, renal failure, urinary tract infection, urinary calculi or urinary incontinence. The presence of conditions that could yield urinary-type symptoms or mimic urological disease (including bowel–urinary tract fistula, dehydration, diabetes insipidus, epididymitis, neuromuscular disease, pregnancy and vaginitis) should also be ascertained. A history of urethral/suprapubic catheterisation or renal dialysis may also allude to the presence of other urological defects.

Lifestyle history

Establish if there are any factors that may increase the individual’s risk of urological disease or worsen the presenting complaint, such as obesity,38 tobacco use (including number and strength of cigarettes inhaled in a day),39 alcohol consumption (including number of standard drinks and type of alcoholic beverage consumed in a day),40 illicit drug use (including type, route and quantity of drug used per day), diet and fluid intake (such as fruit and vegetable consumption, simple sugar intake, omega 3 fatty acid consumption),39,40 quality and duration of sleep (e.g. broken sleep, sleep apnoea)41 and frequency, duration and type of exercise.42

Physical examination

Inspection

Signs that may be indicative of underlying urinary dysfunction include abnormal skin colour (individuals with chronic renal failure may develop dirt-brown skin pigmentation due to impaired urinary pigment excretion and/or anaemia secondary to reduced erythropoietin secretion),24 gouty tophi (the manifestation of white chalky masses of urate crystals on the hands, feet and joints may occur in hyperuricaemia),26 nail markings (leuconychia, the presence of white transverse opaque lines on the nails, may be a sign of hypoalbuminaemia stemming from glomerular disease),24 scars (such as a nephrectomy scar) and long-term urinary drainage devices (such as a urostomy, suprapubic catheter or indwelling urethral catheter). Observation of the client’s urine, including the colour (i.e. red urine related to haematuria, colourless urine due to diabetes insipidus, dark orange-amber urine related to dehydration), odour (as discussed below) and transparency (i.e. cloudy urine from bacteria, urate deposits or leucocytes) can also capture valuable information about an individual’s urological function. Observe also for signs of fluid retention, such as a distended abdomen, puffy eyelids and pedal oedema, as these may be indicative of glomerular disease or renal failure.26 In pertinent cases, inspection may also detect congenital defects of the male urethra, such as hypospadias or epispadias.10

Olfaction

Certain body odours can be indicative of urological or systemic disease. Malodorous urine, for instance, can be a sign of urinary tract infection (faecal or fishy odour), dehydration (strong ammonia odour), diabetes mellitus (sweet odour), phenylketonuria (musty odour) or maple syrup urine disease (sweet maple syrup odour). The consumption of particular foods and medications, including asparagus, vitamin B supplements and antibiotics, can also be responsible for abnormal urine odour.24 An ammonia or fishy breath odour (uraemic fetor) may allude to the presence of uraemia from chronic renal failure.43

Palpation

Palpation over the costovertebral angle (kidney region) and suprapubic area (bladder region) can help to identify the size, contour and tenderness of underlying structures. Signs of tenderness, for instance, may allude to the presence of infection or inflammation, while masses may be indicative of cysts or tumours and unequal kidney size suggestive of hydronephrosis.44 A suitably qualified clinician may also conduct a digital rectal examination in order to assess the size, texture and firmness of the prostate. A tender prostate gland may, for instance, be suggestive of prostatitis, while an indurated and/or nodular prostate may be indicative of prostatic carcinoma.10

Percussion

The application of conventional percussion over the suprapubic region enables the clinician to visualise the border of the bladder, thus aiding the detection of urinary retention. The application of Murphy’s kidney punch can be useful in detecting renal tenderness from conditions such as glomerulonephritis and glomerulonephrosis.44

Auscultation

Auscultation, which plays a minor part in urological assessment, is used primarily to assess the presence of renal bruits. These abnormally harsh sounds, together with hypertension, are suggestive of renal artery stenosis.44

Clinical assessment tools

Examples of instruments that may be used to evaluate the severity or effect of urinary complaints or the effect of treatment on these conditions are listed below.

Interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index

Measures the severity and effect of urinary symptoms in clients with interstitial cystitis.

Diagnostics

Pathology tests

Culture and sensitivity testing of urine

This test allows sufficient numbers of a pathogenic organism to be isolated, identified and quantified, and the antibiotics the microbial strains are sensitive or resistant to, to be determined. This test may be ordered to aid the diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infection.16

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

A BUN test measures the level of urea nitrogen, an end product of protein catabolism, in the blood. Elevated levels of urea may be indicative of impaired renal excretory function. Urological causes of azotemia can be classified as prerenal (e.g. burns, dehydration, excessive protein ingestion or catabolism), renal (e.g. acute tubular necrosis, glomerulonephritis, pyelonephritis, renal failure) and postrenal (e.g. ureteric or bladder outlet obstruction).16

Creatinine

Creatinine is a product of creatine metabolism, an amino acid stored predominantly in skeletal muscle. If skeletal and dietary factors can be eliminated, serum and urine creatinine levels can be a useful measure of glomerular and renal function. Above normal levels of creatinine may, for instance, be a sign of acute tubular necrosis, dehydration, glomerulonephritis, nephritis, nephropathy, nephrosclerosis, obstructive uropathy, polycystic kidney disease, pyelonephritis, renal calculi and renal failure.18

Hair, urine, serum and blood nutrient levels

May be indicated when presenting clinical manifestations are suggestive of nutrient deficiency or toxicity, when the presenting condition is likely to be caused by nutrient deficiency or toxicity, or when the condition is likely to contribute to the development of nutrient deficiency or toxicity. Nutrient tests that are particularly relevant to urological assessment are hair mineral analysis, iron studies, serum vitamin B12, serum vitamin C, serum calcium, serum cholecalciferol, serum magnesium, serum pyridoxine and serum zinc.

Specific gravity (SG)

SG is a measure of urine concentration, which is determined by the number of solutes (i.e. electrolytes, waste products) in the urine. Reduced concentration capacity of the kidneys may result in more dilute urine or a lower SG, which can manifest in glomerulonephritis or severe renal damage. A high SG may be associated with impaired renal dilution capacity, as in nephrotic syndrome. It is important to note that in the presence of glycosuria and proteinuria SG results may be falsely elevated.20

Uric acid

Uric acid is an end product of purine catabolism. Because uric acid levels are maintained by the kidneys, any changes in renal function may adversely affect serum and urine levels. Reduced urine uric acid levels in the presence of hyperuricaemia may be associated with severe renal disease, such as glomerulosclerosis and glomerulonephritis. Elevated urine uric acid levels in the presence of hypouricaemia may be indicative of impaired renal tubular absorption.18

Urinary haemoglobin (Hb)

Hb should not be present in urine, while red blood cells (RBC) should be present only in very small numbers. Any elevation in urinary Hb or RBC may be indicative of urinary tract disease or injury, including calculi, glomerulonephritis, hydronephrosis, renal infarction, malignancy, prostatitis, pyelonephritis, trauma or urinary tract infection.34

Urinary leucocytes or white blood cells

These are normally present in the urine in very small numbers, but when their level is above normal, it may be a sign of urinary tract infection or inflammation, such as cancer, cystitis, glomerulonephritis, nephritis, pyelonephritis and renal calculi.20

Urinary nitrites

These are formed from urinary nitrates in the presence of nitrate reductase – an enzyme secreted by nitrite-forming bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp. and Pseudomonas spp. The presence of urinary nitrites may be indicative of bacteriuria.16

Urinary protein

As these large molecules do not normally pass the glomerular membrane, their presence is an indicator of renal dysfunction. If pre-eclampsia and physical stress can be eliminated as causes, elevated urinary protein levels may be a sign of diabetic nephropathy, glomerulonephritis or nephrotic syndrome.34

Radiology tests

Computed tomography (CT)

CT uses multiple X-ray beams to create cross-sectional images of the kidneys, ureters and bladder. CT imaging is particularly valuable in detecting calculi, congenital anomalies, cysts, haematomas, obstruction, trauma and tumours.45

Intravenous pyelogram (IVP)

IVP uses intravenous contrast media to provide radiographic visualisation of the kidney, ureter and bladder. It can assess structure and function, and may help in the detection of calculi, congenital defects, cysts, glomerulonephritis, haematomas, hydronephrosis, pyelonephritis and tumours.18

Magnetic resonance urography

Uses magnetic and radiofrequency energy to produce images of the kidney, ureters and bladder following fluid and diuretic challenge. The procedure is useful in the evaluation of suspected congenital anomalies, dilated collecting systems, hydronephrosis and obstructive uropathy.46

Plain abdominal X-ray (AXR)

AXR uses electromagnetic radiation to generate images of the kidney, ureter and bladder. This test can be ordered to identify the size, shape and position of these structures, as well as the presence of suspected bladder distension, calculi, congenital defects, haematoma, hydronephrosis, tumours and trauma.20

Renal angiograph

This is an invasive radiological procedure in which the renal artery or vein is injected with contrast media and a series of X-ray images taken of the renal vasculature. The procedure is able to evaluate blood flow dynamics and blood vessel defects, and thus can assist in the detection of arterial stenosis or occlusion, renal artery aneurysm, trauma, tumours and vascular malformation.16

Retrograde pyelography

This procedure provides radiographic visualisation of the renal pelvis, calyces and ureters following cystoscopic-guided ureteric administration of contrast media. The procedure is indicated when abscesses, calculi, congenital anomalies, hydronephrosis, obstruction, strictures and tumours are suspected.16

Ultrasound

Ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to assess the position, size, texture and contour of the kidneys, ureters and bladder. The procedure can be useful in detecting calculi, cysts, bladder diverticulum, congenital anomalies, cystitis, glomerulonephritis, hydronephrosis, obstruction, organomegaly, pyelonephritis and tumours. Ultrasound can also be used to measure bladder volume and residual urine volume.18

Functional tests

Urodynamic studies

These studies evaluate bladder and urethral pressure, sensation, volume, capacity and filling pattern (cystometry), as well as the rate of urination (uroflowmetry). Although the procedure is primarily used to classify the type of urinary incontinence or the cause of bladder dysfunction, urodynamic studies may also allude to the cause of urinary obstruction or retention, such as carcinoma, congenital defects, prostatic hypertrophy and urethral stricture.16

Invasive tests

Biopsy

A biopsy involves the excision of a small sample of tissue and the subsequent microscopic examination of the sample in order to identify cell morphology and tissue abnormalities. A biopsy of urinary tract tissue may assist in the diagnosis of cancer, disseminated lupus erythromatosus, glomerulonephritis, Goodpasture’s syndrome, nephrotic syndrome and pyelonephritis.18

Cystoscopy

This test enables direct visualisation of the urethra, bladder and ureteric orifices through the use of a flexible fibreoptic cystoscope. Cystoscopy can be used as a diagnostic tool to assess the presence of bladder neck contracture, calculi, congenital anomalies, cystitis, diverticulum, foreign bodies, polyps, prostatic hypertrophy, prostatitis, tumours, urethral stricture and urethritis.20