chapter 19 Assessing the Skin

Despite these factors, it is possible to develop a simple, practical approach to most dermatologic problems. If you can assign a skin condition to a broad morphologic group on the basis of its appearance, you can learn or refer to lists of the conditions within the group. After a time, you will find it easier to recognize the primary lesions that identify the morphologic groups and the variations in common skin conditions in each group. Table 19–1 lists the most common skin problems seen in children and classifies them by morphologic appearance.

TABLE 19–1 Morphologic Classification of Common Pediatric Skin Conditions

| Skin Lesion | Examples |

|---|---|

| Macules | Freckles, junctional nevi, tinea versicolor |

| Patches | Café au lait spots port-wine stains, vitiligo |

| Maculopapular rashes | Viral exanthems, drug eruptions |

| Papules | Warts, molluscum contagiosum, insect bites, compound nevi |

| Papules with burrows | Scabies |

| Papules with comedones | Acne |

| Plaques (nonscaly) | Mastocytomas, sebaceous nevus |

| Papulosquamous eruptions | Psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, lichen planus, fungal infections |

| Vesiculobullous eruptions | Friction blisters, acute contact dermatitis, herpes infections, bullous impetigo, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome |

| Eczematous eruptions | Atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, diaper dermatitis |

| Nodules or tumors | Epidermoid or pilar cysts, neurofibromas, lipomas |

| Alopecia | Alopecia areata, trichotillomania, tinea capitis |

Obtaining the History of Skin Problems

Some patients and parents are incredibly observant when it comes to skin, and others notice no details at all. Let both the patient and the parents give their descriptions, then ask for clarification. Use terms they will understand, such as those suggested in Table 19–2.

| Medical Term | Lay Term |

|---|---|

| Macule | Dot |

| Papule | Little bump |

| Nodule | Big bump |

| Plaque | Raised or thickened area |

| Vesicle | Little blister |

| Bulla | Big blister |

| Pustule | Pus pocket, pimple |

| Desquamation | Scaling, flaking |

| Crusts | Scabs |

| Excoriations | Scratch marks |

| Comedones | Blackheads, whiteheads |

History of present illness

Your questions should cover the following points:

Approach to the Physical Examination

Examine the entire skin surface

Primary lesions

Papules

A papule is a small (less than 1 cm) elevated lesion that is palpable above the skin surface. Note the distribution and color. If papules are multiple, are they discrete, or do they coalesce? Comment on the shape in all dimensions (e.g., the papules are polygonal and flat-topped in lichen planus, and they are round and dome-topped with umbilication in molluscum contagiosum (Plate 19–1). Describe any change on the surface, such as scaling or crusting. Palpate the lesion to determine whether it is soft or firm, and try to distinguish in which layer of skin it arises epidermis or dermis.

Plaques

A plaque is a raised lesion in which the surface area is greater than the elevation. Plaques can arise directly from the skin or can develop from a coalescence of papules. They can vary in size from 1 cm to huge plaques covering much of the body. Note whether the surface is smooth or scaly. Comment on any subtle changes, such as the plugging of hair follicles within the plaque (seen commonly in discoid lupus erythematosus). If scaling is present, describe it in detail (see later discussion of scaling). Some eruptions show a combination of scaly papules and plaques; they are termed papulosquamous eruptions. The most common papulosquamous eruptions seen in the pediatric age group are psoriasis (Plate 19–2), pityriasis rosea (Plate 19–3), and fungal infections.

Nodules and Tumors

Nodules and tumors are circumscribed and elevated lesions that are larger than papules. Nodules arise from deeper structures, therefore displaying depth as well as elevation (Plate 19–4). Tumors can arise from deep structures, the dermis, or the epidermis. As with papules, describe the shape, outline, elevation, depth, surface characteristics, firmness of a nodule or tumor, and its mobility on palpation.

Vesicles and Bullae

A vesicle is a small (less than 1 cm) raised cavity containing fluid. A bulla is a larger, fluid-filled lesion (more than 1 cm). Both are called blisters by lay persons. Look at the distribution and arrangement, which may be important for diagnostic purposes. For example, the blisters in poison ivy contact dermatitis are commonly linear in arrangement (Plate 19–5), whereas those of herpes simplex are clustered closely together. Note whether the blisters arise on erythematous skin, such as in a blistering contact dermatitis, or on apparently normal skin, such as with friction blisters. Describe the color of fluid within the lesions—serous, hemorrhagic, or a combination.

Check for the Nikolsky sign in vesiculobullous conditions. The Nikolsky sign exists if the layers of skin can be easily separated with a gentle rubbing or shearing force (Plate 19–6). This phenomenon is seen in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, pemphigus, and some forms of epidermolysis bullosa.

The group of disorders in which blisters are the primary lesions is called vesiculobullous eruptions. There are many causes of vesiculobullous eruptions in children. Some are rare hereditary blistering disorders, such as epidermolysis bullosa. Common infectious diseases, such as varicella (Plate 19–7), bullous impetigo, and herpes simplex, produce vesiculobullous eruptions. Skin conditions due to exogenous factors, such as friction and sunburn, frequently cause blistering. A vesicular reaction may be caused by various types of contact dermatitis, either irritant or allergic in origin. (A prime example of allergic contact dermatitis is that caused by poison ivy, shown in Plate 19–5.) Vascular reactions, such as erythema multiforme and some forms of vasculitis, may cause vesicles.

Wheals or Urticaria

Angioedema is a similar process that occurs deeper in the skin, giving a less well-demarcated localized swelling, which often is tender rather than pruritic. Patients prone to urticaria often have dermatographism, in which the wheals form in lines wherever pressure is exerted on the skin, such as under tight clothing. It can be demonstrated by firmly stroking the letter X on the patient’s back; if dermatographism is present, a urticarial wheal will form within a few minutes (Plate 19–8).

Burrows

Burrows are faint linear tunnels in the layers of the superficial epidermis, usually 2 to 7 mm long (Fig. 19–1). They are the primary lesions in scabies and are most easily found between the fingers and around the wrists and ankles. The female scabies mite (Sarcoptes scabiei) and some of her eggs may be visible only as a tiny black dot at the blind end of the burrow.

FIGURE 19–1 Scabies with typical burrows.

(From Zitelli BJ, Davis HW: Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis, 5th ed. Philadelphia, Mosby, 2007.)

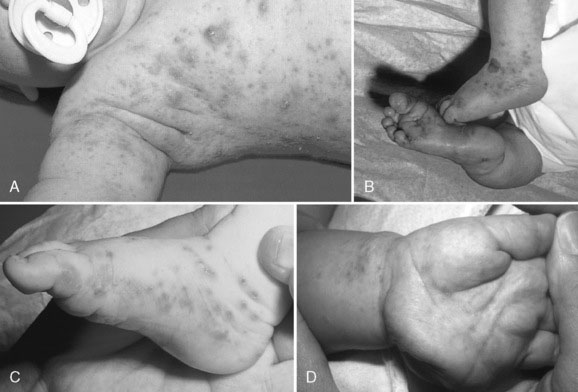

Patients with scabies usually have numerous excoriated inflammatory papules with some burrows among them. The morphology of scabies may vary with age. In an infant, there may be lesions over the entire body, including the face and scalp, whereas in older children and adults, the head area is spared. Infants may present with pustules on the palms and soles, a pattern less common in older individuals. Chronic scabies that has gone undiagnosed for months may appear as crusted nodules rather than the more typical papules and burrows (Plate 19–9).

Secondary lesions

Crusts

Crusting results from the accumulation of dried exudates or transudates on the skin (Plate 19–10). A crust from dried serous fluid is honey-colored and easily dislodged; a crust from purulent material is brown and tightly adherent; and a crust from sanguineous or bloody fluid is red-brown to black and tightly adherent. Crusts are seen on any oozing eruption, such as infected eczema or a vesiculobullous eruption.

Excoriations

Excoriations are defined as linear breaks in the skin, at various depths, caused by scratching.

Special patterns

Some morphologic terms referring to special patterns require further definition:

Eczema and dermatitis

Eczematous disorders are often pruritic and therefore secondarily excoriated as well. They look quite different depending on the stage of the condition. Acute eczemas consist of small vesicles, oozing, crusting, and bright erythema. Subacute eczemas manifest as pink scaly patches or plaques (Plate 19–12). More chronic eczematous disorders frequently show lichenification, a descriptive term meaning lichening of the skin and accentuation of the skin markings. Depending on the history, distribution, and clinical appearance, the term dermatitis must be qualified to refer to atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, irritant or allergic contact dermatitis, or stasis dermatitis.

Color changes

Describing the subtle hue of erythema often suggests a certain diagnosis. For example, erythema is violaceous in lichen planus, salmon-pink in pityriasis rosea, and beefy red in candidiasis (Plate 19–13).

White discoloration can result from the following:

Approach to the Examination of Mucosa and Skin Appendages

Scalp and hair

If alopecia is the presenting problem, decide whether it is diffuse or patchy, inflammatory or noninflammatory, and scarring or nonscarring. Assignment of the alopecia to one of these broad groups simplifies the differential diagnosis. For example, if an alopecia is patchy, nonscarring, and noninflammatory, it is probably either alopecia areata (Plate 19–14) or trichotillomania (hair pulling). The bald patch is smooth in alopecia areata, but broken-off hairs are seen in trichotillomania. In alopecia areata, look for so-called exclamation mark hairs, which are 1 to 2 mm in length, tapered at the attached end, and seen around the periphery of developing bald patches (Fig. 19–2).

Case History 1

What do you expect the physical examination to show? Robert has an extensive papulosquamous eruption most prominent on the trunk, with slight involvement of the proximal limbs and neck. There is sparing of the scalp, face, mucous membranes, palms, and soles. Oval, salmon-pink plaques are arranged parallel to the lines of skin cleavage on his trunk (Christmas tree distribution). The individual plaques are thin and just palpable above the skin surface; most measure about 1 cm, except for a 3-cm-diameter plaque on the left side of his chest (see Plate 19–3). There is scaling around the periphery of most of the plaques, with the free edge of the scale facing toward the center of the lesion (a toeing-in). His fingernails are normal.

Case History 2

At this point, your presumptive diagnosis is that these papules represent angiofibromas, a hallmark of tuberous sclerosis. The history of a seizure and mental slowness is also in keeping with this disorder. You continue the examination, looking particularly for other cutaneous manifestations of this syndrome. There are five faint hypopigmented patches on the trunk and limbs (birthmarks), so you shine a Wood light on the skin, which makes them more obvious. Each is 2 to 3 cm in diameter, oval, and not raised or scaly (Plate 19–15). These patches are called ash leaf macules or patches because of their shape. Joanne also has two firm pink polypoid papules along the lateral aspects of her toenails (periungual fibromas; Plate 19–16). There is a localized leathery-looking plaque on her lower back, a shagreen plaque that represents a fibrous hamartoma.

Case History 3

What specific clinical signs are you now looking for? You suspect that David has contracted a scabies infestation. On examination, you find several small pustules on the palms and soles (a common sign of scabies in an infant). David has an extensive eruption of excoriated papules on his trunk and limbs, and a few on his neck. On careful examination, you find a few 3- to 5-mm linear burrows around his wrists and ankles (see Fig. 19–1). David does not have the typical dry skin of atopic dermatitis.

Krowchuk D.P., Mancini A.J. Pediatric dermatology: a quick reference guide, 1st ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006.

Paller A.S., Mancini A.J. Hurwitz clinical pediatric dermatology: a textbook of skin disorders of childhood and adolescence. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005.

Weinberg S., Prose N.S., Kristal L. Color atlas of pediatric dermatology, 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007.

Weston W.L., Lane A.T., Morelli J.G. Color textbook of pediatric dermatology, 4th ed. St. Louis: MO, Mosby, 2007.