chapter 22 Assessing the Appropriate Role for Children in Health Decisions

The Traditional Role of Parents and Families

Evolving Understanding of Respectful Involvement of Children in Medical Decisions

Assessing the Appropriate Role for Children in Health Decisions

The child’s capacity for communication

Issues

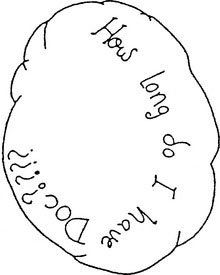

Conveying information to a child about medical interventions is a necessary step in determining the child’s understanding. But how much information is enough? As in communications with parents, you must impart difficult or complex information gradually. If the child’s threshold for understanding has been reached, more information might create anxiety and distress and should be withheld for the moment. Letting the child tell you how much he or she needs to know is an important strategy; it gives the child some sense of control of the situation. Figure 22–1 is the picture that a 12-year-old drew and used to ask a question that was too scary to verbalize.

Case History 1

Strategies

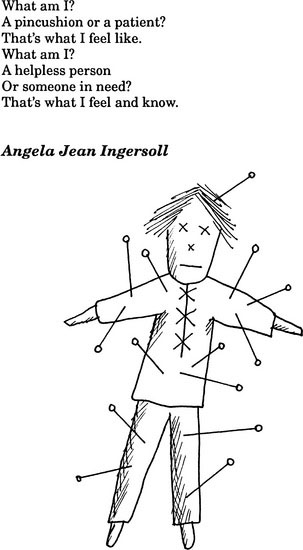

Body outline doll. A soft, simple body-shaped doll (Fig. 22–2), or the child’s own doll is a useful tool for teaching the child about illness as well as assessing the child’s understanding. For Rachel, the doll can represent the angel she wishes to be. Play and discussions involving the doll can help Rachel’s parents and physician better understand how she pictures herself as an angel. Because children use concrete language, parents and caregivers may assume that they understand more than they do; however, children can and do express important issues if the communication tool is appropriate.

Artwork. Children’s artwork can contribute essential information about their awareness, understanding, and fears. Listening to children’s interpretations of their own drawings is an important way for adults to assess their understanding of abstract situations. It is important for Rachel’s physician and family to have a clear understanding of her beliefs. Rachel’s explanation of her drawings of herself as an angel gives them another way of achieving this goal (Fig. 22–3). Asking Rachel the same questions that were asked during play with the body outline doll will help the adults see the topic of angels through Rachel’s eyes.

Capacities for reasoning

Issues

Children’s ability to focus on decision-making depends largely on their sense of the locus of control. Children between ages 6 and 9 years do not generally see themselves as being decision-makers in any meaningful way. By ages 8 to 11 years, children are developing the role-playing skills necessary to weigh different options. By ages 12 to 14 years, these skills are quite well developed and support a youngster’s decision-making capacity. Regardless of age, seriously ill children feel overwhelmed and out of control, as evidenced by the touching drawing and poem shown in Figure 22–4. This lack of control can impair the child’s ability to focus on the issues and decisions.

Case History 2

Strategies

What if. The “what if” activity can help Jason understand abstract situations in more concrete terms. Simple picture cards can be used to represent his choice of transplant list or no transplant list and the consequences of each choice (Fig. 22–5). This strategy is more successful if Jason identifies with the pictures. Therefore, photographs of himself, his family, and their particular situations are best. Jason, at age 11 with 8 years of repeated medical interventions, may well show that he truly understands the consequence of refusing another transplant. His understanding of continued dialysis dependence can become clear. He may believe that the failure of the first two transplants is predictive of another failure. Alternatively, Jason may be depressed or may have lost faith in medicine because of his past experience. The “what if” cards can help demonstrate logical and appropriate reasoning, magical thinking, or confusion.

Concepts of the “good”

Issues

Case History 3

Strategies

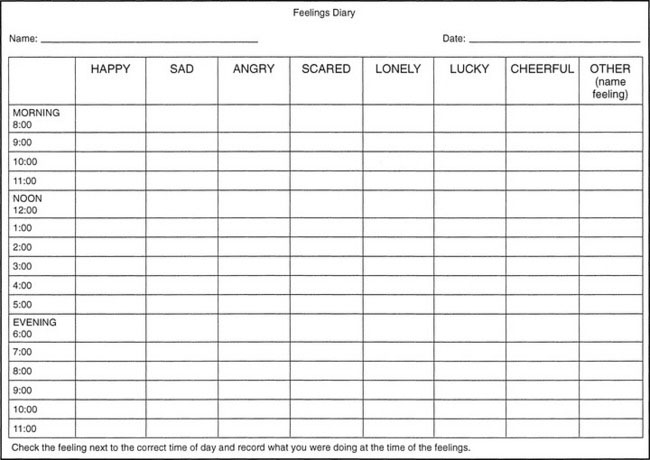

Feelings diary. The goal of the feelings diary is to give Adam the means to express his feelings by asking him to keep a daily record of his good and bad feelings and experiences. In a chart format (Fig. 22–6), Adam could record his feelings and experiences at different times of the day. A careful review of Adam’s diary would give him a visual inventory or “picture” of the mixture of feelings that he has and help him see that they are not all that bad. The next step is to offer counseling designed to build in more good experiences and fewer bad ones when possible. This procedure also gives Adam’s parents and caregivers an idea of what makes him happy. His parents may begin to understand that listening to music and using his computer make Adam happy. Both activities are possible for a patient undergoing home ventilation.

Special considerations with adolescents

Issues

Case History 4

Strategies

Strategies for understanding the emotions involved in adolescent decision-making include activities for self-expression, such as keeping diaries, writing poetry, and art and music (Fig. 22–7). Karen needs to demonstrate some factual information about contraception. More importantly, however, you must determine why this 13-year-old girl is sexually active and plans to continue to be active. Why are her parents not involved in giving her information, guidance, and support?

Anderson P., Sutcliffe K., Curtis K. Children’s competence to consent to medical treatment. Hastings Cent Rep. 2006;36(6):25-34.

Kenny N.P., Downie J., Harrison C. Respectful involvement of children in medical decision making. In: Singer P., Viens A.M., editors. The Cambridge Textbook of Bioethics. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008:121-126.

Miller V.A., Drotar D., Kodish E. Children’s competence for assent and consent: a review of empirical findings. Ethics Behavior. 2004;14(3):255-295.

Sourkes B. Armfuls of time. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995.