CHAPTER ONE ASSESSING MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS

AXIOMS IN ASSESSING MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS

INTRODUCTION

The history provides much information about the pathologic process involved and the impact of the condition on the patient, whereas the orthopedic physical examination is essential to define the anatomic structures involved; together these processes allow differentiation of orthopedic disorders into various categories.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-2 CLINICAL ASSESSMENTS

In clinical practice, assessments occur all day every day, including:

The accuracy of a test for detecting a disease or a condition is determined by sensitivity and specificity. A high sensitivity (or a high specificity) does not suffice to make a test useful in clinical practice; a test should be as sensitive as possible. The sensitivity and specificity of examination procedures and tests can often be found in the literature. Sensitivity and specificity are important characteristics of evidence-based physical assessment procedures but only in the context of a specific disease or condition.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-3 BAYES THEOREM

Rules of Thumb Rationale for use in clinical situations:

The decision of whether to perform a new test depends on the result of the previous test. Procedures with the lowest burden, risk, and costs for the patient are performed first, and those with the highest burden, risk, or costs are reserved for certain patients in which the prior probability is highest. Examination procedures in the context of a low prior probability of disease are rarely, if ever, informative, with the yield of diagnostic testing that will increase the prior probability approximating 50%. Very experienced clinicians intuitively apply these rules and arrange their diagnostic process in such a way that the highest possible yield (a highly probable diagnosis) will be obtained at the lowest possible burden, risk, and cost for the patient. Less-experienced clinicians may learn from experienced colleagues by recalling Bayes theorem and implementing its principles in everyday clinical practice.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-4 PRÉCIS OF PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The history provides much information about what difficulties the patient is experiencing and the impact of these on the patient. Orthopedic examination is essential to define the structures involved; together, these processes allow differentiation of orthopedic disorders into various diagnostic categories (Box 1-1).

HISTORY

OBSERVATION AND INSPECTION

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-7 OBSERVATION AND INSPECTION

A useful approach in clinical examination of the neuromusculoskeletal system is to seek answers to the Critical 5 questions for an orthopedic specialist. Once all five questions are answered, a differential diagnosis can usually be established (Box 1-2).

The physician needs to learn what exacerbates or relieves the symptom pattern. Equally important is how long the complaints have existed (Table 1-1).

PALPATION

NEUROLOGIC EVALUATION

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-16 COMMON AREAS OF MENSURATION

RANGE OF MOTION

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-19 JOINT END-FEEL CATEGORIES

In passive joint motion assessment, the end-feel is important. The accepted end-feel categories are:

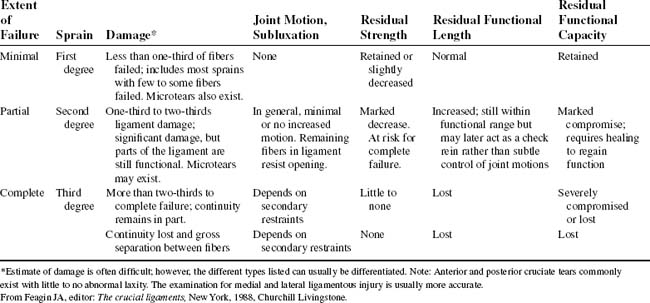

STABILITY TESTING

Because clinical examination reveals the degree of ligamentous or joint sprain (Table 1-2), the examiner must be able to test accurately for joint instability. Stability testing moves joint and periarticular structures through their respective arcs and end-range motions. Stability testing involves stressing ligamentous tissues and joint capsules.

CLINICAL LABORATORY

For the examiner concerned with musculoskeletal disorders, differential diagnosis becomes a challenge. Complete blood and urine tests can help determine a diagnosis (Box 1-3). Diseases of the heart, liver, kidney, pancreas, and prostate can mimic back pain of spinal origin.

BOX 1-3 CLINICAL LABORATORY TESTS

Most laboratory testing has limited utility for orthopedic diagnosis (Table 1-3). As an example, in rheumatoid arthritis, the diagnosis is often established from the history and physical examination; for systemic lupus erythematosus, from the laboratory test antinuclear antibody (ANA); for gout, from a synovial fluid examination; and for ankylosing spondylitis, from a radiograph. In common disorders such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, or muscular strains and sprains, in essence, only a limited diagnostic role exists for laboratory tests, primarily to exclude other diagnostic possibilities.

TABLE 1-3 LABORATORY STUDIES USEFUL IN DIAGNOSING LOW BACK SYNDROMES

| Test | Measurement | Low Back Implication |

|---|---|---|

HLA, Human leukocyte antigen.

Adapted from Pope ML: Occupational low back pain, assessment, treatment and prevention, St Louis, 1991, Mosby.

The simplest orthopedic screen includes rheumatoid factor, ANA, and uric acid, although more elaborate screens are available, which may include erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), antistreptolysin O titer, protein electrophoresis, quantitative immunoglobulins, and ANA subsets such as anti-Ro and anti-La, anti-Sm, and anticentromere antibodies.

Synovial Fluid Testing

Normal synovial fluid is a hypocellular, avascular connective tissue. In disease, the synovial fluid increases in volume and can be aspirated. Synovial fluid is a transudate of plasma supplemented with high–molecular-weight, saccharide-rich molecules. The most notable of these is hyaluronan, which is produced by fibroblast-derived type B synoviocyte (Box 1-4). Variation in the volume and composition of synovial fluid reflects pathologic processes within the joint.

BOX 1-4 NORMAL SYNOVIAL FLUID

Adapted from Klippel JH, Dieppe PA: Rheumatology, vol 1-2, ed 2, London, 1998, Mosby

| Osmolarity | 296 mOsm/L |

| pH | 7.44 |

| Carbon dioxide pressure | 6.0 kPa (range 4.7–7.3) |

| Oxygen pressure | <4.0 kPa |

| Potassium | 4.0 mmol/L |

| Sodium | 136 mmol/L |

| Calcium | 1.8 mmol/L |

| Urea | 2.5 mmol/L |

| Uric acid | 0.23 mmol/L |

| Glucose | 100 mmol/L |

| Chondroitin sulfate | 40 mg/L |

| Hyaluronate | 2.14 g/L |

| Cholesterol | Small amounts |

| Total protein | ∼25 g/L |

| Albumin | ∼8 g/L |

| α1-antitrypsin | 0.78 mcg/L |

| Ceruloplasmin | ∼43 mg/L |

| Haptoglobin | ∼90 mg/L |

| α2-macroglobin | 0.31 g/L |

| Lactoferrin | 0.44 mg/L |

| IgG | 2.62 g/L |

| IgA | 0.85 g/L |

| IgM | 0.14 g/L |

| IL-1β | 20 pg/mL |

| IL-2 | 15.1 U/mL |

| TNF-α | 1.38 hg/mL |

| INF-α | 350 U/mL |

| INF-δ | 13.7 U/mL |

IgA, Immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IL, interleukin; INF, interferon; TNF, tumor-necrosis factor.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-22 SYNOVIAL FLUID

For three significant aspects, analysis of synovial fluid differs from other body fluids:

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING MODALITIES IN ORTHOPEDICS

Plain-Film Radiography (Conventional Radiography)

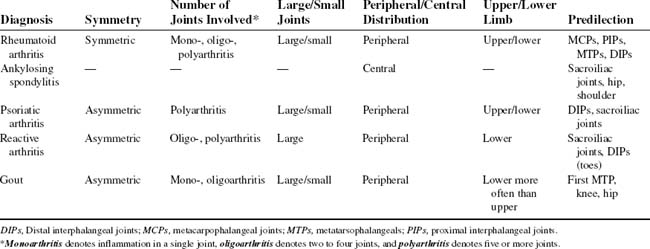

Plain-film X-ray examination is an efficient way to discover dislocations, fractures, the static component of anatomic subluxations, certain types of stress injuries, metastatic disease, some types of primary tumors, metabolic disease, degenerative arthropathic diseases (Table 1-4), and abnormalities in the growth plate.

TABLE 1-4 PLAIN-FILM EVALUATION IN DEGENERATIVE ARTHROPATHIC DISORDERS

| Diagnosis | Site of Plain-Film Findings |

|---|---|

| Psoriatic arthritis | Hand, sacroiliac joints (common); pubis symphysis, hip, knee (less common) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Wrist and hand, shoulder, knee, cervical spine, hip |

| Spondyloarthropathy | Sacroiliac joints, thoracolumbar spine |

| Osteoarthritis | Lumbosacral spine, hip, knee, foot and ankle, hand |

A radiologic evaluation of the traumatized sites should include films of the adjacent joints. If a need rises for special projections, other radiologic investigation may be necessary (Table 1-5).

TABLE 1-5 PREFERRED RADIOGRAPHIC VIEWS IN SKELETAL TRAUMA

| Area | Specific Views |

|---|---|

| Skull |

From Gustilo RB, Kyle RF, Templeman DC: Fractures and dislocations, vol 1, St Louis, 1993, Mosby.

Care must be taken to investigate the possibility of associated injuries in trauma victims (Table 1-6). Patients may not realize that such injuries have occurred.

TABLE 1-6 INJURIES ASSOCIATED WITH SKELETAL TRAUMA

| Fracture | Associated Injury |

|---|---|

| Bone and Bone | |

| Spine | Remote additional spinal fracture |

| Chest wall | Scapula fracture |

| Anterior pelvic arch | Sacrum fracture or dislocated sacroiliac joint |

| Femoral shaft | Fracture or fracture-dislocation of hip |

| Tibia (severe) | Dislocated hip |

| Calcaneus | Fractured thoracolumbar spine |

| Bone and Viscera | |

| Chance fracture of spine | Ruptured mesentery or small bowel |

| Lower ribs | Laceration of liver, spleen, kidney, or diaphragm |

| Pelvis | |

| Pelvis | Ruptured bladder or urethra |

| Ruptured diaphragm | |

| Bone and Vascular | |

| Ribs 1, 2, or 3 | Ruptured aorta |

| Sternum | Myocardial contusion |

| Pelvis | Laceration of pelvic arterial tree |

| Distal third femur | Laceration of femoral artery |

| Knee dislocation | Popliteal artery laceration |

Adapted from Rogers LF, Hendrix RW: Evaluating the multiple injured patient radiographically, Orthop Clin North Am 21(3):444, 1990.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-23 ARTHRITIDES: DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL PROGRESSION ASSESSMENT STEPS IN RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS, PSORIATIC ARTHRITIS, ANKYLOSIS SPONDYLITIS, AND OSTEOARTHRITIS

Adapted from Ory PA: Radiography in the assessment of musculoskeletal conditions, Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 17(3):495-512, 2003.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-24 ASSESSMENT ABILITIES AND LIMITATIONS OF PLAIN-FILM RADIOGRAPHY

Tomography

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-25 ASSESSMENT ABILITIES AND LIMITATIONS OF COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

For patients who have sustained head trauma with skull fractures, MRI is an efficient way to identify the early signs of cerebral edema. The test procedure of choice for diagnosing metastatic disease is an MRI scan (Table 1-7).

TABLE 1-7 MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING VERSUS COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

| Anatomic Area | Indications | Recommended Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| Brain (including brainstem) |

CT, Computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasonography.

* Consult radiologist for imaging options.

From Brier SR: Primary care orthopedics, St Louis, 1999, Mosby; originally courtesy of Robert Goodman, MD, South Suffolk MRI, PC, Bayshore, New York.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-27 FOR CERTAIN PATHOLOGIC CONDITIONS, MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING IS THE DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURE OF CHOICE

Contrast Arthrography

The conventional use of arthrography in musculoskeletal disease involves the use of air to distend a synovial joint and a radiopaque contrast agent to outline anatomic structures. The injection of contrast material into the joint space results in a radiographic outline of the cartilage, menisci, ligaments, or synovium. Conventional arthrography is used in diagnosis of the scope and magnitude of orthopedic trauma to the shoulder, wrist, knee, and ankle (Table 1-8).

TABLE 1-8 JOINTS TYPICALLY STUDIED WITH COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHIC ARTHROGRAPHY AFTER TRAUMA

| Joint | To Observe |

|---|---|

| Knee | Meniscus, cruciate and collateral ligaments, hyaline cartilage tears, osteochondral defects |

| Shoulder | Rotator cuff, glenoid labrum disruption |

| Hip | Hyaline cartilage integrity and tears, prosthetic joint loosening |

| Wrist | Triangular fibrocartilage, intercarpal ligament integrity |

| Elbow | Hyaline cartilage integrity, osteochondral defects |

| Ankle | Ligamentous tears, osteochondral defects |

| Temporomandibular | Disc and condylar integrity |

Adapted from Gustilo RB, Kyle RF, Templeman DC: Fractures and dislocations, vol 1, St Louis, 1993, Mosby.

Radionuclide Scanning

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-29 ASSESSMENT ABILITIES AND LIMITATIONS OF RADIONUCLIDE SCANNING

Diagnostic Ultrasound

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-30 ASSESSMENT ABILITIES AND LIMITATIONS OF ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Myelography

Traditional myelographic techniques involve the introduction of small amounts of water-soluble contrast medium into the subarachnoid space, either through a lumbar approach below the level of the conus medullaris or at the level of C1–C2 through a posterolateral approach. Standard films of the spinal canal are made to determine the presence or absence of a filling defect. In cases of acute spinal trauma, myelography may be used in conjunction with CT. Myelography remains valuable in evaluating intrinsic spinal cord lesions, nerve root lesions, and dural tears associated with severe trauma (Box 1-5).

Thermography

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 1-31 ASSESSMENT ABILITIES AND LIMITATIONS OF THERMOGRAPHY

Electrodiagnostic Testing

Although electrodiagnostic testing provides valuable information, it does not stand alone as a diagnostic entity (Table 1-9). The data obtained must be correlated with the physical examination findings and case history.

TABLE 1-9 STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF ELECTRODIAGNOSTIC TESTING

| Testing Modality | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Nerve conduction velocity | Helpful in ruling out peripheral entrapment neuropathic conditions (e.g., prolonged latencies exhibited in carpal tunnel syndrome, tarsal tunnel syndrome) and ulnar neuropathic variations | Provides imperfect sensitivity; limited localization and determination of injury severity; timing of study an important factor |

| F waves | Provides screening for late motor response with distal sweeps starting at the foot | Evaluates motor reflex only; possibly evaluates abnormal findings only in the presence of multiple-level injury |

| H reflex | Equivalent of ankle joint reflex; evaluates monosynaptic reflex with sensory and motor S1 function | Provides assessment of S1 nerve root only |

| SSEPs | Helpful in documenting sensory pathway disturbances in proximal neural injury and central conduction delays, as in myopathies and multiple sclerosis | Offers imperfect localization; findings are rarely abnormal if results of other electrodiagnostic tests are within normal limits |

| Needle EMG | Useful in assessing conductivity of neural tissues; helpful in determining site and severity of lesion; may be helpful in early assessment of recovery, screening for fibrillation potentials, and signs of denervation from nerve root compression disorders | Unable to detect denervation potentials for 14 to 28 days after injury; provides imperfect sensitivity; study timing an important factor; proximal lesions sometimes inaccessible anatomically; effectiveness reduced after surgery |

EMG, Electromyography; SSEPs, somatosensory-evoked potentials. Adapted from Brier SR: Primary care orthopedics, St Louis, 1999, Mosby.