chapter 5 Assessing Congenital Anomalies

The importance of recognizing parents’ needs throughout the interview cannot be overemphasized. This issue is especially vital when you are dealing with the parents of a child who has a birth defect, as noted in Chapter 1. Remember the spectrum of emotions that parents may feel at the child’s birth and long afterward: shock, guilt, shame, anger, and denial.

The Logic Behind the Diagnostic Approach

Definition of Terms

Minor anomalies

Constellations of minor anomalies

Minor anomalies include upward- or downward-slanting palpebral fissures, small or low-set ears, ear tags or pits, clinodactyly (incurving of the finger, generally the fifth, often associated with a dysplastic middle phalanx), or widely spaced nipples. Variations in features found frequently in the population (in more than 4% of individuals) are considered normal variants, not minor anomalies. They include mild webbing (syndactyly) between the second and third toes (see Fig. 4-22) and hydroceles (i.e., fluid accumulation surrounding the testes). Because of the large numbers of minor anomalies and potential variations, it would be impractical to list them all here.

Sequences and syndromes

Sequence

Comparing patterns

Several computer programs are now available that can generate such lists after a constellation of identified anomalies has been entered (see http://www.possum.net.au/ or http://www.lmdatabases.com/). These programs provide descriptions and often photographs of patients with different syndromes. The major advantage of using such programs is having access to their encyclopedic quality, but their usefulness is always limited by the accuracy of the history and physical findings that the physician “feeds” them. Computer programs cannot take the history or perform the physical examination; only a clinician can do this. Further, your clinical judgment is required to determine if any of the suggested diagnoses is, in fact, likely to be the correct one.

As a result of the many advances in our understanding of the molecular basis of development and the progress of the Human Genome Project, we are learning the genetic basis for many syndromes. Nevertheless, although we may know the molecular basis for a syndrome, we still may not have any diagnostic laboratory test for it. For some syndromes, a test may be available to confirm a diagnosis made on clinical grounds. (A useful resource for determining whether a genetic test is available for any particular syndrome is the GeneTests Web site: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/GeneTests/?db=GeneTests).

Obtaining The History

History of pregnancy, labor, and delivery

Pregnancy History

The pregnancy history is outlined in Chapters 1 and 4. Be sure to relate calendar dates to gestation time. For example, note that the mother had a viral illness at 7 gestational weeks, not “on January 16.” Specifically inquire about the course of the pregnancy.

Significant Questions

Family history

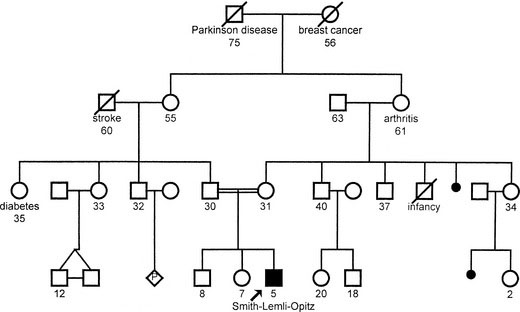

Sketch out the family pedigree, covering, in general, three generations. Using the details of pedigree construction and the appropriate pedigree symbols (found in any introductory genetics textbook), begin with the parents, recording each pregnancy and the outcome (including stillbirths and miscarriages) in chronologic order, from eldest to youngest, from left to right. The easiest way to stay organized is to begin in the middle of the page. An example is shown in Figure 5-1.

Approach To the Physical Examination

What is normal?

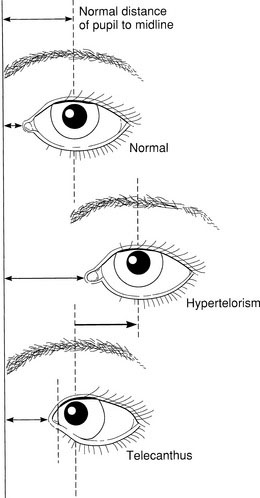

Nevertheless, it also is important to bear in mind the considerable variability of syndromes and genetic disorders. The features of various syndromes also vary with age. Often, even within the same family, two affected individuals may have quite different manifestations. Sometimes the particular features observed in another affected family member may help you establish the diagnosis if these features are absent in the child. Just as you need to appreciate the range of normal variation, you also must recognize the variability of these disorders. Although obvious, distinctive features may make the diagnosis of a particular syndrome easy, those features may be rare, even in an affected child. More common features may be more likely to be found. For example, heterochromia iridis (a difference in color of the iris in the two eyes) may be a distinctive feature allowing the diagnosis of Waardenburg syndrome, but telecanthus, that is, lateral displacement of the inner canthi, is seen more frequently (see the discussion later in this chapter and Fig. 5-2).

Two basic techniques of physical examination

Describing Visual Observations: Qualitative Versus Quantitative Techniques

The Qualitative Approach

A working group of experts has published a series of articles defining the terms used to describe the morphology of regions of the body, including the head and face and the hands and feet. They describe how to observe and, where possible, how to measure the feature, and a clear illustration of each feature is provided (see http://www.wileyinterscience.com/journal/ajmg).

The physical examination

General Assessment

General Assessment Questions

Specific Assessments

Eyes

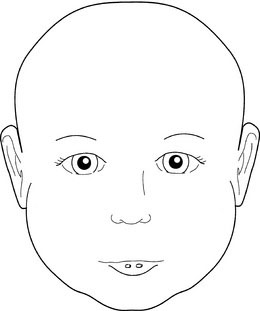

Although the eyelids of a newborn frequently are edematous, it is important to examine them carefully. Start with the set of the eyes. Are they deeply set or prominent? Note the size and slant of the palpebral fissures. Is hypotelorism or hypertelorism present? These findings may be part of a total pattern of midline facial maldevelopment that may accompany similar brain abnormalities. Holoprosencephaly may be found with hypotelorism; absence of the corpus callosum may be found on computed tomography scans in a child with hypertelorism. Distinguish hypertelorism from telecanthus (see Fig. 5-2) and from a flat nasal bridge and epicanthal folds. Standards for the normal values for intercanthal and interpupillary distances may be found in various reference sources.

Beyond the lids, look at the globe itself: cornea, iris, lens, sclera, and retina. Do you find normal red reflexes in both eyes? If not, the problem might be (1) corneal clouding, seen in persons with storage diseases, such as the mucopolysaccharidoses; (2) cataracts, which may be found in persons with galactosemia and in a number of different syndromes; or (3) a retinoblastoma, a malignant tumor that can have important genetic implications. The number of potential abnormalities of the eyes, orbits, and periocular region, including those in the eyebrows, lids, and lashes, is enormous; many of them are listed in Table 5-1. An ophthalmology consultation can be very helpful in dysmorphologic diagnosis.

| Feature | Conditions to Watch For | |

|---|---|---|

| Orbits (the set of the eyes) | Hypotelorism/hypertelorism | Prominent/deeply set eyes |

| Palpebral fissures: size and slant (up, down) | Prominent/flat supraorbital ridges | |

| Eyebrows | High arched | Thick |

| Synophrys (eyebrows that meet in the middle) | Thin | |

| Medial flare | Absent | |

| Eyelashes | Long | Absent |

| Eyelids | Absent or fused | Ptosis |

| Epicanthal folds | Epicanthus inversus | |

| Telecanthus | Coloboma or dermoid | |

| Globe | Anophthalmia | Microphthalmos |

| Cornea | Corneal clouding | Microcornea |

| Lens | Cataract | Dislocated lens |

| Stellate pattern | ||

| Iris | Aniridia | Brushfield spots |

| Coloboma | Lisch nodules | |

| Heterochromia | ||

| Sclerae | Blue sclerae | Telangiectasis |

| Retina | Albinism | Optic atrophy |

| Pigmentary changes | Coloboma | |

| Cherry-red spot | Detachment | |

| Motility | Nystagmus | Strabismus |

Ears

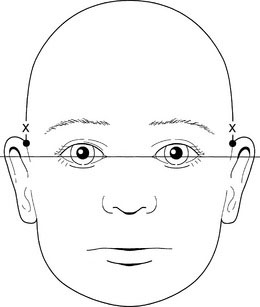

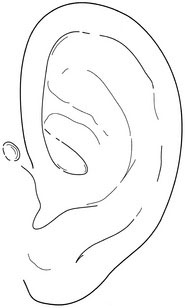

The best way to assess the set of the ears is to examine the child from the front, with the child’s head held erect and the eyes facing forward. Then draw an imaginary line between the two inner canthi of the eyes and extend it around the head. The superior attachment of the pinna of the ear should be at or above that line (Fig. 5-3).

Next, note the size and shape of the ears. Interestingly, the right ear often is slightly larger than the left ear. Examine the preauricular region carefully for tags, pits, and fistulas (Fig. 5-4). These findings can be important clues to other abnormalities, especially those involving the branchial arches and, often, hearing deficits.

FIGURE 5-4 Ear pits, found in the preauricular region, may be important clues to other abnormalities.

Nose and Mouth

When evaluating the child with a cleft lip, with or without cleft palate, it is important to examine the lower lips of both the child and the parents for lip pits (Fig. 5-5). The van der Woude syndrome is an autosomal dominant syndrome in which a parent may have only the lip pits but his or her child may have the syndrome’s full expression with clefts of the lip, palate, or both. The parents of such a child face a risk as high as 50% of having another affected child, whereas parents whose child has only an isolated cleft lip have only a 3% to 5% risk of recurrence.

Neck and Chest

Ambiguous Genitalia

The parents’ first question upon the birth of their child is often, “Is it a boy or girl?” They expect an immediate, definitive answer. Ambiguity of the genitalia makes this determination difficult (see Chapter 4), and how you handle this issue from the beginning is critical.

Limbs

Note the palmar flexion creases (see Fig. 5-6). A single transverse crease or a bridging of the two transverse palmar creases reflects a short palm. A single transverse palmar crease is found unilaterally in 4% of the normal population, bilaterally in 1% of the normal population (twice as often in males as in females), and in about 50% of children with Down syndrome.

Note the length and mobility of the limbs:

Other aspects to consider are as follows:

Skin

Examine the skin with the child unclothed. You may note diffuse skin changes, such as thin, thick, coarse, elastic, or lax skin, or localized changes such as hemangiomas, nevi, café au lait spots, or hypopigmented macules (see Fig. 4-24). The last two features are among the important cutaneous findings in the phakomatoses, such as neurofibromatosis and tuberous sclerosis. Examination with a Wood ultraviolet lamp, which makes depigmented lesions more obvious, often is helpful. Other abnormalities of pigmentation, ichthyosis, or photosensitivity may be present. Besides the scalp hair and nails, remember that body hair and sweat glands are skin appendages, and they also may be affected in the child with an ectodermal dysplasia. Many cutaneous findings are signs of hereditary syndromes that are associated with a predisposition for malignancies to develop. Readers interested in more detail on skin signs of genetic disorders may read one of several excellent reference works on the genodermatoses.

Cohen M.M. Jr. 2nd ed. The child with multiple birth defects. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

De Paepe A., Deveroux R.B., Dietz H., et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for the Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genetics. 1996;62:417-426.

Gorlin R.J., Cohen M.M.Jr, Hennekam R.C.M. 4th ed. Syndromes of the head and neck. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Hall J.G., Allanson J.E., Gripp K.W., et al. 2nd ed. Handbook of physical measurements. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Jones K.L. 6th ed. Smith’s recognizable patterns of human malformation. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Royal Children’s Hospital. Pictures of Standard Syndromes and Undiagnosed Malformations (POSSUM). (Web site) http://www.possum.net.au/

Reardon W. The bedside dysmorphologist. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Elements of morphology: standard terminology. Am J Med Genetics. January 2009;149A:1-127. (special issue) http://www.wileyinterscience.com/journal/ajmg

Spitz J.L. 2nd ed. Genodermatoses: a clinical guide to genetic skin disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

London Medical Databases Ltd. Winter-Baraitser dysmorphology database. (Web site) http://www.lmdatabases.com/