CHAPTER TWO ASSESSING CARDINAL MUSCULOSKELETAL SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

INTRODUCTION

The part or region under evaluation must be adequately exposed and in good lighting. Many mistakes are made simply because the examiner does not insist on removing enough of the patient’s clothing to allow proper evaluation and inspection (Fig. 2-1). When examining the involved extremity, the uninvolved extremity is always used for comparison.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 2-1 VISUAL INSPECTION

Systematically, visual inspection focuses on four areas:

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 2-2 PALPATION

Four elements are the focus of palpation:

CARDINAL SYMPTOMS

Pain and Sensibility

Among presenting symptoms, pain is usually most important for the patient. Among presenting signs, swelling of a joint or periarticular tissue is important. With regard to pain, the examiner must be certain of the site of origin and distribution. The patient’s verbal description may be misleading. The patient should be able to point to or define the site of maximal intensity and map out the area over which pain is experienced.

Factors that exacerbate or ameliorate the pain are important. Pain during an activity suggests a mechanical problem, particularly if it worsens during use and quickly improves when resting. Pain while at rest, and pain that is worse at the beginning rather than at the end of use, implies a marked inflammatory component. Night pain is a distressing symptom that reflects intraosseous hypertension and accompanies serious problems, such as avascular necrosis, bone neoplastic activity, or bone collapse adjacent to a severely arthritic joint. Persistent bony pain is characteristic of neoplastic invasion. The activities that create a mechanical pain may provide clues as to the appropriate diagnosis. Periarticular problems are often induced by a specific type of activity but are also divided by region (Table 2-1).

| Region | Periarticular Syndrome |

|---|---|

| Jaw | Temporomandibular joint dysfunction (myofascial pain syndrome) |

| Shoulder |

Adapted from Kelley WN, et al: Textbook of rheumatology, ed 5, Philadelphia, 1997, WB Saunders.

Disability and Handicap

Disability is present when a tissue, organ, or system cannot function adequately. A handicap exists when disability interferes with a patient’s daily activities or social or occupational performance. A marked disability does not necessarily cause a handicap. Conversely, minor disability may produce a major handicap. Both states of disability and handicap require separate assessment, with the evaluation of disability being a purely medical activity, whereas handicap assessment is often a medicolegal function. Patients’ perceptions of their problems is a product of their adaptation to the depreciated tissue, as well as aspirations for recovery (Box 2-1).

BOX 2-1 ABILITY DEPRECIATION ASSESSMENT

Adapted from Demeter SL: Disability evaluation, St Louis, 1996, Mosby.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 2-5 SPECIFIC ELEMENTS TO CONSIDER IN ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING ASSESSMENT

Toileting and Elimination Management

SYSTEMIC ILLNESS

Emotional Lability

Patients with emotional lability are usually anxious to the extent that they may have some severe disease or injury that will cause permanent disfigurement or disability. Pain is a potent cause of anxiety. Much of the important information regarding the patient’s perception of pain and accommodation is gleaned during the clinical evaluation from the history, either during the examination or from a health assessment questionnaire.

Referred Symptoms

The afferent pain fibers originating from the same area demonstrate extensive convergence onto the dorsal horn relay cells. In certain cases, the convergence may take place by fibers from different areas, causing relay cell activation by pain originating in different body parts. This mechanism underlies the phenomenon of referred pain (e.g., pain originating in the heart is often felt at the inner aspects of the left arm). Referred pain is either caused by convergence of pain fibers from both zones onto the same spinal relay cell or caused by facilitation of somatic signals during excessive pain traffic from a visceral source. Classic examples of this phenomenon include the referral of neck or shoulder pain to the upper arm (Table 2-2).

TABLE 2-2 CERVICAL SPINE SYNDROMES REFERRING PAIN TO THE UPPER EXTREMITY

| Lesions Producing Neck and Shoulder Pain | Lesions Producing Predominantly Shoulder Pain |

|---|---|

Modified from Kelley WN, et al: Textbook of rheumatology, ed 5, Philadelphia, 1997, WB Saunders.

CARDINAL SIGNS

Diffuse Joint Swelling

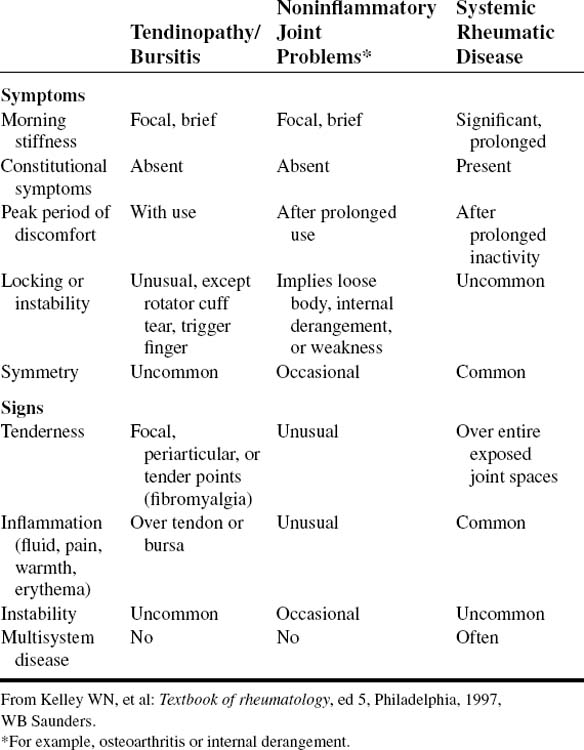

Soft-tissue swelling is pathognomonic of inflammation (Table 2-3). Joint, bursal, or tenosynovial inflammation is almost invariably accompanied by the presence of an inflammatory exudate. An important step in confirming inflammation is the detection of effusion. In small joints, cross-fluctuation is applied with the examiner’s index finger pressing dorsally while the joint is gently squeezed from the sides between the examiner’s index finger and thumb.

| Tissue | Indicative of |

|---|---|

| Joint synovium/effusion | Inflammatory joint diseases |

| Subcutaneous tissue | Inflammatory joint disease |

| Bursa/tendon sheath | Inflammation of structure |

| Articular ends of bone | Osteoarthritis |

Erythema

Discoid lupus has a virtually diagnostic appearance and distribution (Table 2-4) but may require histopathologic and immunofluorescence studies. Misdiagnosis of acute lupus can occur in patients expressing other photosensitive eruptions and in patients with conditions that produce vascular dilation (Table 2-5). A clinical history and examination are usually sufficient to discriminate acute lupus from other photosensitive eruptions.

TABLE 2-5 REVISED CRITERIA FOR THE CLASSIFICATION OF SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS (1982)

| Criterion | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1. Malar rash | Fixed erythema, flat or raised, over the eminences, tending to spare the nasolabial folds |

| 2. Discoid rash | Erythematous raised patches with adherent keratotic scaling and follicular plugging; atrophic scarring may occur in older lesions |

| 3. Photosensitivity | Skin rash as a result of unusual reaction to sunlight, revealed by patient history or physician observation |

| 4. Oral ulcers | Oral or nasopharyngeal ulceration, usually painless, observed by a physician |

| 5. Arthritis | Nonerosive arthritis involving two or more peripheral joints, characterized by tenderness, swelling, or effusion |

| 6. Serositis |

ECG, Electrocardiogram; LE, lupus erythematosus.

From Tan EM, et al: The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of SLE, Arthritis Rheum 25:1271, 1982.

Features of dermatomyositis rash allow discrimination from lupus. These features include occasional nasolabial fold involvement, prominent heliotrope and extrafacial involvement, erythema following the course of extensor tendons, and scaling and fissuring of lateral aspects of the fingers (mechanic’s hands). A heliotrope rash and Gottron papules are characteristic and possibly pathognomonic cutaneous features of dermatomyositis. The heliotrope rash consists of a violaceous to dusky erythematous rash, with or without edema, in a symmetrical distribution involving periorbital skin.

Tenderness

The only reliable finding on examination in fibromyalgia is the presence of multiple tender points. The diagnostic utility of a tender point evaluation has been objectively documented with the use of a dolorimeter or algometer, pressure-loaded gauges that accurately measure force per area, and with manual palpation. The criteria of at least 11 of 18 tender points are recommended for classification purposes but should not be considered essential in individual patient diagnoses. Patients with fewer than 11 tender points can be diagnosed with fibromyalgia, provided other symptoms and signs are present. An investigation must be made to determine whether the fibromyalgia is primary or secondary. The Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs helps differentiate neuropathic pain and fibromyalgic pain (Box 2-2).

BOX 2-2 LEEDS ASSESSMENT OF NEUROPATHIC SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS (THE LANSS PAIN SCALE)

Adapted from Kaki AM, El-Yaski AZ, Youseif E: Identifying neuropathic pain among patients with chronic low-back pain: use of the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs Pain Scale, Reg Anesth Pain Med 30(5):422.e1-422.e9, 2005.

Painful Arc of Movement

When the tendon is subjected to disease or excessive load, it may rupture. In tendon disease or injury less than rupture, tendon inflammation usually results. Tendinopathy is detected by eliciting a painful arc of active movement in the plane of action of the affected tendon. Passive movement in the same plane is almost pain free (Table 2-6).

Fixed Deformity

Although articular deformity may be observed at rest, most become more apparent when the limb is bearing weight or being used. The examiner should determine whether the deformity is correctable or noncorrectable. Many conditions are associated with characteristic deformities, but no deformity is pathognomonic of any single disease (Table 2-7). Shorthand terms are used for combined deformities, such as swan-neck finger deformity for hyperextension at the proximal and fixed flexion at the distal interphalangeal joints.

| Lower Limb | Upper Limb |

|---|---|

DIPs, Distal interphalangeal joints; MCPs, metacarpophalangeal joints; PIP, proximal interphalangeal joints.

Movement

Every joint has a normal range of motion. The range of motion for any joint varies with age, gender, and ethnic origin. A range of movement that is beyond the upper limit represents hypermobility. Ranges below the lower limit represent hypomobility. The normal joint range of motion is diminished by joint inflammation or by irreversible damage to the joint structures. In trauma or disease, movement is first lost from the extreme end ranges. Increasing joint damage results in more profound loss of range of motion. The complete loss of movement of a joint is known as fixation ankylosis or joint ankylosis, depending on soft-tissue versus bony involvement, respectively. Fixation or joint ankylosis is further complicated by the involvement or loss of multiple planes of motion (Table 2-8).

| Type | Planes | Joints |

|---|---|---|

| Hinge | One | Elbow, knee, ankle, MCP, PIP, DIP, MTP |

| Two-way hinge | Two (circumduction) | Wrist, trapeziometacarpal |

| Ball and socket | All planes | Shoulder, hip |

DIP, Distal interphalangeal; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

Hypermobility is recognized by a series of passive maneuvers collectively known as the 9-point scale of Beighton (Box 2-3). The Beighton modification of the Carter and Wilkinson scoring system has been used for many years as an indicator of widespread hypermobility. A high Beighton score by itself does not mean that an individual has HMS. It simply means that the individual has widespread hypermobility. Diagnosis of Hypermobility Syndrome or HMS should be made using the Brighton Criteria. The Beighton score is an easy to administer 9-point scale where points are given for the performance of five maneuvers. It is generally considered that hypermobility is present if 4 out of 9 points are scored. The scale was not designed for clinical use and has been criticized because it only samples a few joints and gives no indication of the degree of hypermobility.

BOX 2-3 MODIFIED BEIGHTON MOBILITY INDEX

1 point is awarded for each side of the body for each extremity clinically involved.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 2-11 BRIGHTON CRITERIA (DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR HYPERMOBILITY SYNDROME)

From R. Grahame, Pain distress and joint hyperlaxity, Joint Bone Spine 67 (2000), pp. 157–163

Minor criteria

Stability

The stability of a joint depends partly on the integrity of its articulating surfaces and partly on its intact ligaments. When a joint is unstable, mobility is abnormal. When testing for abnormal mobility, the examiner must ensure that the muscles controlling the joint are relaxed. A muscle in strong contraction can often conceal ligamentous instability (Table 2-9).

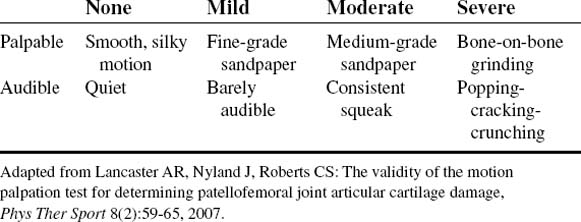

Crepitation

Crepitation is a palpable crunching sensation present throughout the movement of the involved joint or enthesis structure. Fine crepitation may be audible only by stethoscope and is not transmitted through the adjacent bone. Fine crepitation may accompany inflammation of the tendon sheath, bursa, or synovium. Coarse crepitation may be audible at a distance and is palpable through the bone. Coarse crepitation usually reflects cartilage or bone damage (Table 2-10).

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 2-12 CREPITUS NOISES (OTHER THAN FINE OR COARSE)

Muscular Atrophy

Muscle atrophy is a common sign but can be difficult to detect, particularly in older adults. Synovitis quickly produces local spinal reflex inhibition of muscles acting across the joint. Atrophy can be rapid (within several days) in septic arthritis. Severe arthropathy produces widespread periarticular wasting. Localized atrophy is more characteristic of a mechanical tendon or muscle problem or nerve entrapment. Disuse atrophy is complex and highly regulated biochemical process (Table 2-11).

TABLE 2-11 SIGNALS INVOLVED IN DISUSE-INDUCED MUSCLE ATROPHY

| Signals | Finding | Function |

|---|---|---|

| PI3K, Akt | Decreased |

Signal abbreviations: ACTIIB, Myostatin receptor; Akt, serine/threonine kinase; Bcl-3, transcriptional coactivtor; Calcineurin, serine/threonine phosphatase; c-REL, NF-kB family transcription factor; E1F4B, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B (homo sapiens); ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FOXO, Forkhead family of transcription factor; JNK, c-JUN N-terminal kinase; MAFbx, muscle atrophy f-box ubiquitin ligase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; MuRF1, muscle ring finger 1 ubiquitin ligase; Myostatin, inhibitor of skeletal muscle mass; p38, p38 isoform mitogen activated protein; p50, NF-kB family transcription factor; p70S6K, 70-kDa ribosomal protein s6 kinase; PHAS-I, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Adapted from Zhang P, Chen X, Fan M: Signaling mechanisms involved in disuse muscle atrophy, Med Hypoth 70(2):314–316, 2008.

Cramps and Spasm

Muscular spasm, or tremor (Table 2-12), may occur at rest or with movement. Spasms and tremors occur in the normal individual with metabolic and electrolyte alterations. Cramping is a common complaint after excessive sweating and subsequent hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, or hyperuricemia (electrolyte imbalance).

| Cause | Type and Rate of Movement | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Fine, rapid, 10 to 12/sec |

From Barkauskas VH et al: Health & physical assessment, ed 2, St Louis, 1998, Mosby.

Tetany

Hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia often cause the involuntary spasms of skeletal muscle, which resemble cramping. Tetanic cramps can be elicited by repeatedly percussing the motor nerve that leads to a muscle group contraction-cramp-spasm at frequencies of 15 to 20 per second. Chvostek sign is the spasm of facial muscles produced by tapping over the facial nerve near its foraminal exit. Chvostek sign may also occur with normocalcemia, as well as with hypocalcemia.

(0)

(0) (5)

(5) (0)

(0) (5)

(5) (0)

(0) (5)

(5) (0)

(0) (5)

(5) (0)

(0) (5)

(5) (0)

(0) (5)

(5) (0)

(0) (5)

(5)