CHAPTER 31 ASCITES

INTRODUCTION

Ascites is excessive fluid in the peritoneal space. It is suggested clinically by the finding of shifting dullness and confirmed by imaging such as ultrasonography. Causes can be broadly categorised as portal hypertension-related or non-portal hypertension-related (Table 31.1). The latter include reduced plasma oncotic pressure, peritoneal inflammation, disruption to lymphatic drainage and increased vascular permeability. Despite this diversity in possible cause and mechanism, portal hypertension due to cirrhosis accounts for approximately 80% of cases in Western countries. Peritoneal malignancies and right heart failure account for most of the remaining cases. Tuberculosis is a common cause in patients from endemic areas. Although acute portal vein thrombosis commonly results in transient ascites, chronic portal vein obstruction does not usually cause ascites in the absence of underlying liver disease.

| Portal hypertention-related | Non-portal hypertention-related |

|---|---|

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), an infection of ascitic fluid with a single bacterial species in the absence of any primary intra-abdominal source, may complicate the clinical course of patients with preexisting ascites, often resulting in an exacerbation of peritoneal fluid accumulation. Less commonly, ascites develops de novo as a consequence of SBP. Most instances of SBP occur in cirrhotic patients and clinical studies have identified several subgroups at particularly high risk (Table 31.2). Overall, SBP is present in up to 20% of all cirrhotic patients undergoing paracentesis, although the incidence is notably lower in recent outpatient-based series. SBP is also well recognised to occur in patients with acute liver failure and those with nephrotic syndrome and other hypoproteinaemic states.

TABLE 31.2 Proven risk factors for the development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis

INITIAL INVESTIGATION

History taking and physical examination are directed towards the range of possible aetiologies listed in Table 31.1, with particular emphasis on the more common possibilities, such as liver disease, right heart failure, peritoneal malignancies and, depending on patient demographics, tuberculosis. The possibility of underlying cirrhosis should not be dismissed in patients without peripheral stigmata of chronic liver disease, such as palmar erythema and spider naevi, as these are often absent, especially in those with non-alcoholic aetiologies.

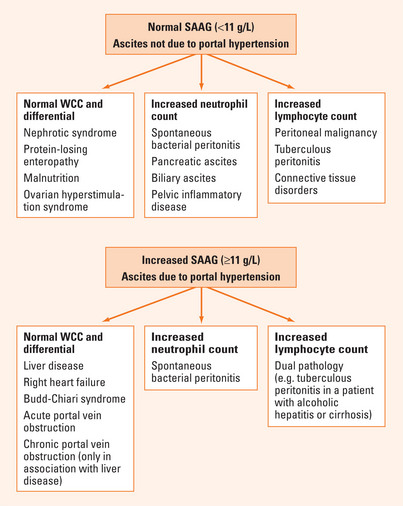

Calculation of the SAAG complements the clinical assessment in correctly differentiating patients with ascites related to portal hypertension (gradient ≥11 g/L) from those with non-portal hypertension-related aetiologies (gradient <11 g/L) in over 97% of instances. The accuracy of this ratio obviates the need in routine practice for more invasive investigations for portal hypertension, such as measurement of the hepatic venous pressure gradient.

Further investigation is mandatory to determine the actual cause of ascites within the two broad categories of portal hypertension-related and other aetiologies. Consideration of the ascitic WCC and differential in combination with the SAAG is of particular value (Figure 31.1). The ascitic WCC is usually normal (total count <500/μL; neutrophil count <250/μL) in patients with uncomplicated portal hypertension-related ascites, such as due to cirrhosis, and raised in all non-portal hypertensive aetiologies, with the exception of hypoalbuminaemic states and disorders associated with increased vascular permeability, such as the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Portal hypertension-related ascites (SAAG ≥11 g/L)

Patency of the portal and hepatic veins is usually adequately assessed by Doppler-ultrasound or dynamic computed tomography (CT). A high index of clinical suspicion is important for diagnosing hepatic veno-occlusive disease and Budd-Chiari syndrome, the latter resulting from hepatic venous outflow block. Tender, non-pulsatile hepatomegaly is a clinical hallmark of these disorders, although can be difficult to detect when ascites is tense. An underlying hypercoagulable state, most commonly related to a myeloproliferative disorder, is present in approximately 75% of patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome and should be sought. The possibility of an underlying malignancy should also be excluded. Associated thromboses in the inferior vena cava and/or portal vein are present in up to 20% of cases.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

The spectrum of clinical features of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) extends from a fulminant presentation with peritonism and shock to an asymptomatic state manifest only by deterioration in laboratory variables. Abdominal pain with fever or hypothermia, often with an increased volume of ascites which may become refractory to diuretic therapy, are characteristic features. However, the majority of patients present with such non-specific symptoms as general malaise, anorexia, nausea or vomiting. Presentation with deterioration in mental status due to precipitation or exacerbation of hepatic encephalopathy is well recognised. Consequently, a high index of suspicion is mandatory if patients with SBP are to be identified and this diagnosis should be sought in any patient with ascites whose clinical status deteriorates.

An ascitic fluid neutrophil count ≥250/μL is the single most reliable test for SBP, with sensitivity approaching 90%. Other causes of neutrocytic ascites (as listed in Figure 31.1) must be excluded but, due to the relative frequencies with which these occur in cirrhotic patients, most instances of a raised ascitic neutrophil count in patients with cirrhosis are due to SBP. The sensitivity of traditional ascitic fluid culture is only 33%. This is improved to around 75% by the bedside inoculation of ascitic fluid into blood culture bottles. Gram stain of ascitic fluid is usually negative, as the concentration of infecting bacteria is generally only very low. Since neither the ascitic fluid neutrophil count nor ascitic culture has 100% sensitivity for SBP, even in combination, it is appropriate to make a clinical diagnosis of this disorder in patients with a suggestive clinical picture, even when these standard tests are negative. Assessment for the presence of bacterial DNA in ascites may be helpful in this latter circumstance, but is not yet widely available in clinical practice. The SAAG has no value in identifying patients with SBP. This gradient remains ≥11 g/L in patients with underlying portal hypertension-related ascites and <11 g/L in those with SBP complicating ascites of another aetiology, such as nephrotic syndrome.

Chylous ascites

When ascites appears milky, the triglyceride content should be measured in order to differentiate between true chylous and pseudochylous ascites, the latter due to scattering of light by aggregates of cholesterol, phospholipid and protein derived from degenerating malignant or inflammatory cells. Lymphatic obstruction in association with lymphoproliferative disorders or tuberculosis is a common cause of chylous ascites. This may also occur in patients with nephrotic syndrome and those with uncomplicated cirrhosis, due to rupture of overloaded lymphatics.

TREATMENT

Portal hypertension-related ascites

As sodium retention is a key feature in the pathogenesis of ascites related to portal hypertension, the goal of medical therapy is to induce a negative sodium balance by use of diuretics in combination with dietary sodium restriction, aiming for loss of body weight in the order of 0.5–1.0 kg/24 h, without precipitating hyponatraemia or azotaemia (Table 31.3). Refractory ascites, defined by lack of response to a sodium-restricted diet and high-dose diuretic therapy, occurs in a minority of patients. Second-line options for this group are listed in Table 31.3. Specific interventions may be necessary in carefully selected patients with ascites due to Budd-Chiari syndrome or veno-occlusive disease. These include thrombolytic therapy, angioplasty with or without venous stenting, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), surgical portacaval or mesoatrial shunt and orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). Treatment of any underlying hypercoagulable state is mandatory in those with Budd-Chiari syndrome.

TABLE 31.3 Treatment options for ascites related to portal hypertension

| Treatment | Example |

| First-line | Dietary sodium restriction (80 mmol/day) |

| Diuretics: spironolactone ± frusemide | |

| Fluid restriction only if hyponatraemic | |

| Second-line | Therapeutic paracentesis |

| Peritoneovenous shunt | |

| Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) | |

| Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) |

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)

Although resolution of SBP is usually achieved with the use of appropriate antibiotics and despite improvements in the general medical care of cirrhotic patients, the in-hospital mortality rate remains 20%–40%. This is largely related to underlying hepatic decompensation and a high prevalence of hepatorenal syndrome. The latter occurs in approximately 30% of patients with SBP, predominantly in those with pre-existing renal impairment, and is progressive despite cure of infection in half of these cases. The development of renal failure is the most important predictor of in-hospital mortality associated with SBP. Survivors of an episode of SBP should be evaluated for orthotopic liver transplanation in view of the high risk of recurrence and poor overall prognosis.

Aslam N, Marino CR. Malignant ascites. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2733-2737.

Navasa M, Rodes J. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis. Liv Int. 2004;24:277-280.

Riordan SM, Williams R. Infection and the intestinal flora in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2006;45:744-757.

Romney R, Mathurin P, Ganne-Carrie N, et al. Usefulness of routine analysis of ascitic fluid at the time of therapeutic paracentesis in asymptomatic outpatients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:275-279.

Runyon BA, Montano AA, Akriviadis EA, et al. The serum-ascites albumin gradient in the differential diagnosis of ascites is superior to the exudates/transudate concept. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:215-220.

Such J, Frances R, Munoz C, et al. Detection and identification of bacterial DNA in patients with cirrhosis and culture-negative, nonneutrocytic ascites. Hepatology. 2002;36:135-141.