CHAPTER 27 Arthroscopy of the Small Joints of the Hand

Introduction

The past 25 years have been witness to a virtual explosion of interest and application of arthroscopy in the orthopedic surgeon’s armamentarium. Beginning as a diagnostic tool, largely for conditions in large joints such as the knee and shoulder, the arthroscope soon developed into a therapeutic tool for a procedure with well–documented advantages over open procedures. Next, intermediate–size joints (such as the wrist and elbow) became amenable to arthroscopic procedures—due in large part to the reduction in size of arthroscopic tools. This, too, followed the pattern of diagnostic procedures followed by therapeutic applications. With further reduction in the dimensions of arthroscopic equipment, we now have the capability to enter very small joints—such as the carpometacarpal and metacarpophalangeal joints of the hand.1–3 Although largely limited to diagnostic procedures, innovations are currently emerging in the use of the arthroscope for therapeutic intervention. Only time will tell if true advantages can be found in the application of arthroscopic technology to these small joints.

First Carpometacarpal Joint

Arthroscopy of the first carpometacarpal (CMC) joint was developed and described nearly 10 years ago.1,2 The first CMC joint is particularly attractive as a joint available for arthroscopic evaluation because of its relative depth, highly curved articular surfaces, and the nearly circumferential nature of the stabilizing ligaments. Each of these factors makes complete viewing of the joint difficult with arthrotomy, unless highly destructive capsulotomies are carried out through these vital ligaments. As such, the use of the arthroscope was initially proposed for a diagnostic joint evaluation (if nothing more).

Early on it became quite clear, however, that the arthroscope could be a useful tool to help visualize the adequacy of reduction of fractures involving the articular surfaces of the trapezium or the base of the first metacarpal (such as with a Bennett’s fracture)—as well as for the debridement of an arthrotic joint. With miniaturization of thermocouple probes, a technique for an arthroscopically guided shrinkage of the joint capsule for the treatment of pain due to joint capsule laxity was developed—as well as arthroscopically guided arthroplasty for the treatment of end–stage arthrosis.

Indications

The principle indications for arthroscopy of the first CMC joint are, in general, the same as for other joints. These include the evaluation of a painful joint that is suspicious for arthrosis or ligament injury, the treatment of two–part fractures of the base of the first metacarpal, retrieval of floating loose bodies or foreign objects, and the irrigation of a septic joint. There has been a persistent interest in using the arthroscope as a means of performing a minimally invasive resection of arthritic joint surfaces and to facilitate the percutaneous interposition of tendon or other materials.2

Regional Anatomy

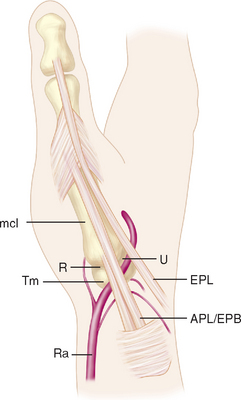

The skin overlying the first CMC joint is glabrous only on the palmar surface. Immediately deep to the skin and superficial to the deep fascia are numerous veins, including the principal tributaries forming the cephalic vein system. Within the periadventitial tissue of these tributaries are the major volar (S1) and major dorsal (S2) divisions of the superficial radial nerve, which are found just deep to the veins (Figure 27.1).

Several muscles and tendons cross the joint, beginning anteriorly with the abductor pollicis brevis—which originates from the anterior surface of the trapezium (Figure 27.1). Just lateral to this is the tendon of abductor pollicis longus, inserting into the posterior base of the first metacarpal. The tendon of extensor pollicis brevis passes distally just posterior to the abductor pollicis longus. Just superficial to the posterior joint capsule of the first CMC joint is the deep division of the radial artery, crossing the first CMC joint deep to the extensor pollicis longus tendon before coursing anteriorly between the proximal metaphases of the first and second metacarpals. Between the proximal epiphyses of the first and second metacarpals is the intermetacarpal ligament, which is entirely extracapsular.

Joint Anatomy

The first CMC joint is a bi–sellar—a double saddle joint formed by the distal articular surface of the trapezium and the base of the first metacarpal. The articular surface along the major axis of the trapezium is concave in the medial–lateral direction and the articular surface along the minor axis is convex in the antero–posterior direction. The converse relationship is found with the base of the first metacarpal, where the articular surface is concave in the antero–posterior direction and convex in the medial–lateral direction. Although a joint capsule surrounds the entire joint, only 3/4 is reinforced by capsular ligaments.4,5

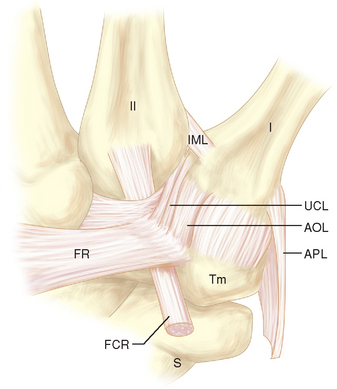

The anterior edge of the first CMC joint is reinforced by the anterior oblique ligament (AOL) complex, which is composed of superficial and deep divisions (Figure 27.2). The superficial division (AOLs) spans nearly the entire anterior edge of the joint and attaches to the anterior surface of the trapezium just proximal to the articular surface and just distal to the articular surface of the base of the fist metacarpal. The deep division (AOLd) is a well–demarcated thickening of the superficial band found just medial to the midline of the superficial division.

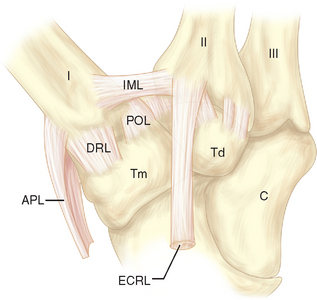

Often there is a distinct medial edge separating the AOLd from the AOLs. It is the deep division of the AOL that is often referred to as the “beak” ligament. The orientation of the fibers of the AOLs is slightly oblique, passing proximal to distal from lateral to medial. The fiber orientation of the AOLd is essentially proximal to distal. The extreme lateral (ulnar) surface of the joint is reinforced by the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL), which has fibers oriented in a proximal to distal direction (Figure 27.2). The lateral 30% of the posterior surface of the joint capsule is reinforced by the posterior oblique ligament (POL) (Figure 27.3). The fiber orientation of the POL is slightly oblique, passing from proximal and medial to distal and lateral.

The remaining posterior joint capsule is reinforced by the dorsoradial ligament (DRL) (Figure 27.3). The fiber orientation of the DRL is generally proximal to distal. The joint capsule immediately deep to the tendon of abductor pollicis longus is not reinforced by a ligament. Although there is a distinct border between the AOLs and AOLd, there are no reliable demarcations between the remaining ligaments.

Portals

There are two recognized portals for arthroscopy of the first carpometacarpal joint. The naming of portals is related to their relationship with the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus tendons. The 1–R portal is established at the joint line just radial to the abductor pollicis longus tendon (Figure 27.1). The 1–U portal is established at the joint line just ulnar to the extensor pollicis brevis tendon (Figure 27.1).

Technique

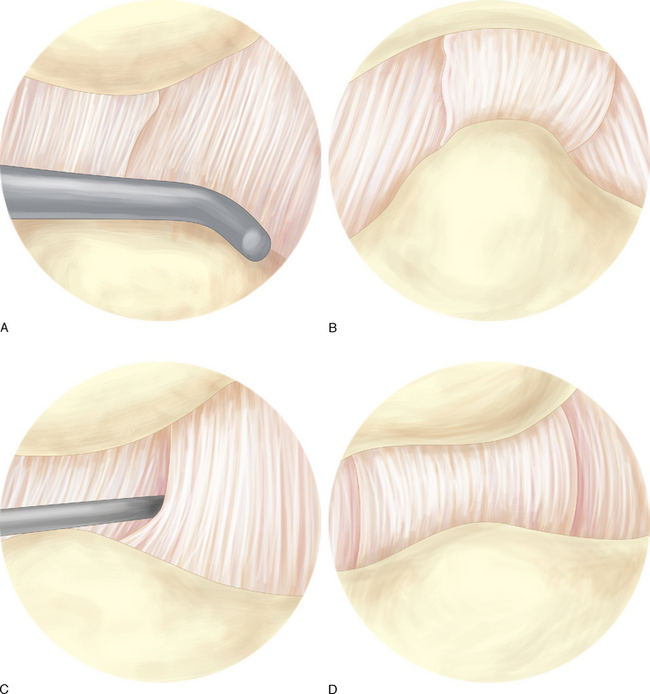

The author typically orients the camera and angles the arthroscope lens in a manner that places the image of the base of the first metacarpal at the top and the trapezium at the bottom. A comprehensive inspection of the articular surfaces is carried out. Next, the intra–articular appearance of the capsular ligaments is noted. It is best to use the probe to validate the integrity of these structures, rather than simply relying on their visual appearance.

The dorsoradial ligament, posterior oblique ligament, ulnar collateral ligament, and deep portion of the anterior oblique ligament can typically be visualized from the 1–R portal (Figure 27.4a through d). The superficial and deep portions of the anterior oblique ligament, ulnar collateral ligament, and posterior oblique ligament can be visualized through the 1–U portal (Figure 27.4a through d).

Procedures

Staging Arthritis

The precise staging of arthritic involvement of the articular surfaces of the first CMC joint is easily accomplished with the arthroscope. This is important in those patients with painful instability of the first CMC joint in whom one is considering performing an extra–articular ligament reconstruction.6 If substantial arthrosis is present, but is not yet radiographically evident, a ligament reconstruction would be considered contraindicated. The most common locations for initial involvement of articular cartilage destruction in degenerative arthritis are the central aspect of the trapezial surface and the ulnar third of the metacarpal surface.

Resection of Joint Surface

There may be some indication for partially resecting either the base of the first metacarpal or the distal surface of the trapezium, although one would think that this would need to be accompanied by another procedure to either stabilize the joint or interpose some material (such as a section of tendon or fascia).2 This was advocated by Menon, where a strip of flexor carpi radialis was interposed arthroscopically after arthroscopic resection of the arthritic joint surfaces.

Reduction of Intra–Articular Fracture

Next, a 0.045 K–wire is advanced into the base of the first metacarpal under fluoroscopic guidance in a line that will either skewer the small fragment upon reduction or will penetrate an adjacent bone to stabilize the reduction. The arthroscope is introduced in the standard fashion, as is a small shaver. The shaver is used to evacuate the intra–articular hematoma universally present. A careful assessment of the articular surfaces and the capsular ligaments is made. Once clear visualization is possible, the fracture is manipulated into an acceptable reduction under arthroscopic guidance. Once an acceptable reduction is achieved, the assistant advances the previously placed K–wire for secure fixation of the fracture. Final radiographs are obtained, and external dressings with reinforcement are applied (as in an open reduction procedure).

Metacarpophalangeal Joints

Arthroscopy of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints of the hand is rarely performed, but may have limited applications.3 One must remember the advantages versus limitations of open versus arthroscopic procedures before deciding which technique to use. The advantages of open procedures typically hinge on the access to regions for procedural tasks, whereas the disadvantages include surgical scars, potential soft–tissue destabilization, and limitation of visualization in deep recesses. Arthroscopy offers the advantages of superior visualization of most regions of a joint that is otherwise difficult to access in an open procedure, through very small incisions with minimal impact on the status of contiguous tissues.

Indications

Indications for arthroscopy of the MCP joints are poorly worked out at this time, but may include assessment of arthritis, irrigation of a septic joint, retrieval of foreign bodies, and the identification and possible reapproximation of collateral ligaments avulsed from either the proximal phalanx or the metacarpal.7

Anatomy

Regional Anatomy

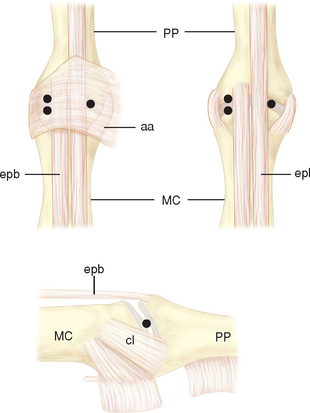

The tendons on the dorsal surfaces of the MCP joints share a common feature: the extensor hood (Figure 27.5). At the level of the joint, the extensor hood is composed of the extrinsic extensor tendon(s) and the sagittal fibers passing toward the volar plate. The extensor tendons for the thumb include the extensor pollicis brevis (radially) and longus (ulnarly). For the index through small fingers, the extensor digitorum communis tendon passes across the MCP joint as the radial–most tendon. Each finger also has an independent proprius tendon, although the extensor indicis proprius and extensor digiti minimi (quinti) tendons are the most widely recognized. These tendons do not insert directly into the proximal phalanx but are connected to the dorsal joint capsule and hence indirectly insert into the phalanx.

Portals

There are two recognized portals for arthroscopy of the MCP joints (Figure 27.5). The naming of the portals is related to the relationship with the extensor tendons. The radial portal is established at the joint line just radial to the extrinsic extensor tendons. The ulnar portal is established at the joint line just ulnar to the extrinsic extensor tendons.

Procedures

Diagnosis of Collateral Ligament Injury

Most ligament injuries about the MCP joints are treated well with closed means. However, the Stener–type lesion creates a situation that is less likely to result in successful closed management. In the Stener lesion, the distally avulsed collateral ligament is displaced and trapped under the free proximal edge of the extensor hood.8 Although the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb is the avulsion injury most commonly associated with a Stener lesion, it can occur in the fingers.8–10 This is particularly so with the ulnar collateral ligament of the index finger MCP joint and the radial collateral ligament of the small finger MCP joint. The arthroscope provides a minimally invasive means of readily identifying the presence of a Stener–type lesion in any of the digits.

Reapproximation of Collateral Ligament Avulsion Injury

Ryu has advocated arthroscopic techniques as the definitive treatment for thumb Stener lesion injuries of the ulnar collateral ligament.7 After verifying the presence of the Stener lesion, the ligament is “hooked” by a probe and drawn back deep to the adductor apponeurosis—where it comes to rest adjacent to its normal attachment point on the ulnar rim of the base of the proximal phalanx. From here, it is treated as a nondisplaced collateral ligament injury. The author has no personal experience with this technique, but instead opts for an open procedure to stabilize all ulnar collateral ligament injuries with measurable instability.

1 Berger RA. A technique for arthroscopic evaluation of the first carpometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg. 1997;22(A):1077-1080.

2 Menon J. Arthroscopic management of trapeziometacarpal arthritis of the thumb. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:581-587.

3 Ryu J, Fegan R. Arthroscopic treatment of acute complete thumb metacarpophalangeal ulnar collateral ligament tears. J Hand Surg. 1995;20(A):1037-1042.

4 Bettinger PC, Linscheid RL, Berger RA, Cooney WPIII, An K-N. An anatomic study of the stabilizing ligaments of the trapezium and trapeziometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg. 1999;24(A):786-798.

5 Bettinger PC, Berger RA. Functional ligamentous anatomy of the trapezium and trapeziometacarpal joint. Hand Clin. 2001;17(2):151-168.

6 Eaton RG, Littler JW. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg. 1973;55A:1655-1666.

7 Ishizuki M. Injury to collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal ligament of a finger. J Hand Surg. 1988;13A:444-448.

8 Schubiner JM, Mass DP. Operation for collateral ligament ruptures of the metacarpophalangeal joints of the fingers. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71B:388-389.

9 Stener B. Displacement of the ruptured ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint of the thumb: A clinical and anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1962;44B:869-879.

10 Wolf BA, Cervino AL. Rupture of the radial collateral ligament of the fifth metacarpophalangeal joint. Annals of Plas Surg. 1988;21:382-387.