CHAPTER 23 Arthroscopically Assisted Treatment of Intraosseous Ganglions of the Lunate

Introduction

Intraosseous ganglia of the carpal bones are an infrequent cause of chronic wrist pain. The pathogenesis remains obscure.1,2 Bone scans and computerized tomography (CT) are used to distinguish these radiolucent carpal lesions from other pathologies, in particular degenerative cysts and osteoid osteomas.1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will demonstrate the bony extent of the lesion and may help to delineate the presence of an extraosseous extension of the ganglion.3

Persistence and severity of symptoms rather than radiological findings determine the need for further management.4 Curettage and bone grafting have been performed for patients with constant symptoms that have severely restricted their occupational or recreational activities.1–6 Clinically, the patients improve. However in up to 40% symptoms persist that affect function.1,2 The authors have published a minimally invasive technique of lunate ganglion grafting with the aim of reducing the morbidity that has been seen with open techniques.7

Pathology

Theories of pathogenesis of ganglia have included synovial herniation, neoplasia, metaplasia of mesenchymal precursor cells, proliferation of synovial rest cells, and traumatic mucoid degeneration of connective tissue.1,2 The shear stresses concentrated at the scapholunate ligament insertion may predispose some individuals to developing the precursor cells that form the intraosseous ganglion.8 Rather than proliferating dorsally from the scapholunate ligament, the cells head into the lunate itself.

Intraosseous ganglia are pathologically identical to the soft-tissue variety, with a thin wall of compressed collagen and fibroblasts containing a clear viscous fluid that has a high concentration of hyaluronic acid.1–4,6,8–11 There is no endothelial or synovial lining. A thin sclerotic margin of bone often surrounds the ganglion. Some authors have suggested that this represents an attempt by the host bone to repair the defect within the lunate.2 Bone scans invariably show increased uptake localized to the involved carpal bone. The advantages of arthroscopic surgery versus open techniques to treat lunate ganglion cysts include a lower morbidity and less risk of damaging the scapholunate ligament.

Indications

The patient presents with persistent dorsal wrist pain and swelling in the perilunate region that is exacerbated by activity and reduced grip strength. The decision to operate is based on the persistence and severity of the symptoms rather than on the outcome of the investigations, which help to localize the pathology. Preoperative symptoms often interfere with function at work or during recreation.1,2,4

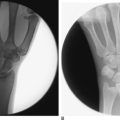

Patients were not considered for surgery unless they had been symptomatic for at least six months and had failed a trial of activity, NSAIDs, and splints. Assessment included clinical examination for local tenderness and carpal stability. Radiographs usually revealed an eccentrically placed radiolucent lesion with a thin sclerotic margin contained within and not expanding the lunate (Figure 23.1).

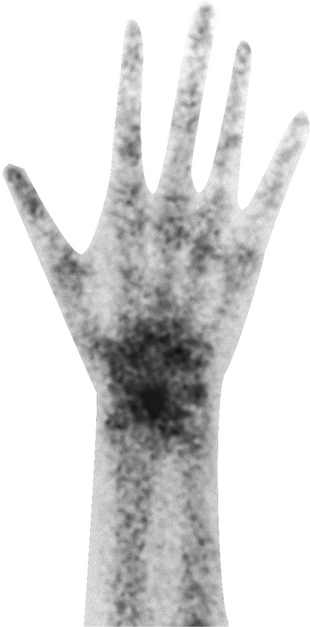

All patients had a preoperative technetium 99 radionuclide bone scan demonstrating focal increased uptake within the lunate and no other site within the wrist (Figure 23.2). This investigation helped to confirm that the patients’ symptoms were related to the intraosseous ganglion prior to any intervention. Patients who had a negative bone scan were not offered surgical treatment.

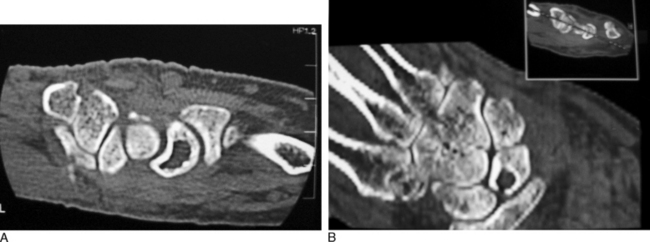

CT scans were used to define the location and extent of the lesion, which aided surgical planning. Localization of the cyst is particularly important with this technique, as the cyst may be volar or dorsal. Figure 23.3 shows a typical coronal CT scan in which the ganglion located close to the scapholunate ligament can be seen to perforate the cortex of the lunate at the site of attachment of the ligament. It is a common radiological finding, and confirms its origin as a ganglion from the scapholunate ligament. Some surgeons have previously interpreted this as a fracture.

Contraindications

Lesions with more sinister pathology of lesion need to be excluded. These are rare and can be differentiated with imaging. Other common pathological conditions that affect the lunate include Kienbock’s diseases and avascular necrosis, which produces sclerosis and often collapse of the proximal convexity of the lunate 22 (Figure 23.4a). Ulnar carpal impaction is also common, but this affects only the ulnar side of the lunate and is often associated with a kissing lesion of the ulnar head (Figure 23.4b). Bone islands (Figure 23.4c), osteoid osteoma, and other lesions are rare. CT scans can help differentiate these lesions.

Surgical Technique

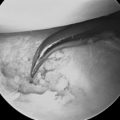

The arm is suspended on Chinese finger traps with 10 pounds of traction. Routine arthroscopy is performed via a 3-/,4 portal and a 6-R portal created with trans-illumination and insertion of a needle.12 It is not usually possible to visu-alize the ganglion through the arthroscope because the lesion is intraosseous. However, intra-articular extension can occur and may be predicted by MRI or CT scan. The fluoroscopy unit is positioned so that the surgeon can switch between assessment of the joint surface with arthroscopy and assessment of the skeletal anatomy with fluoroscopy (Figure 23.5).

A trocar and cannular are positioned on the lunate under arthroscopic vision and strategically positioned at the site of the lesion as determined by the preoperative imaging (Figure 23.6). A small-joint cannula is used as a drill guide to protect the adjacent soft tissue. The scapholunate ligament can often be used as an approximate guide to the position of the ganglion arthroscopically. Satisfactory positioning of the drill tip is then confirmed in the anteroposterior and lateral planes using fluoroscopy.13

The drill is then advanced into the body of the lunate corresponding to the site of the intraosseous ganglion as previously identified on the CT scan. If the lesion is on the volar aspect of the lunate on CT scan, a volar portal is used to drill the lunate (Figure 23.7). If it is on the dorsal aspect, the 3-/,4 portal is used—with the scope in the 6-R portal (Figure 23.6). Fluoroscopy is used to confirm the position of the drill.

The method of establishing the volar portal used by the senior author is an inside-out technique, which is created by placing the scope into the 3-/,4 portal. The scope is advanced into the interligamentous sulcus between the radioscaphocapitate (RSC) and long radiolunate (LRL) ligaments (Figure 23.8). The scope is withdrawn from the trocar and a small Wissinger rod is advanced through the sulcus into the volar wrist. With pressure on the Wissinger rod, the skin over the rod is incised. Care is taken to ensure that the rod passes to the radial side of the FCR tendon to avoid injury to the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. The scope is then positioned over the Wissinger rod on the volar aspect of the wrist and advanced into the wrist. The senior author believes this technique is much simpler than other published techniques, which require an open approach or outside-in techniques.

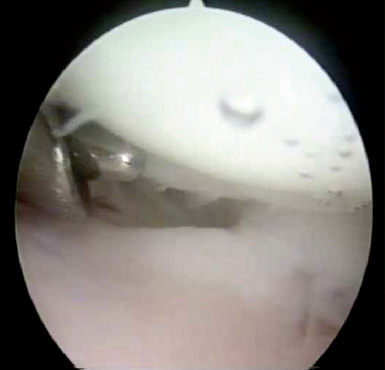

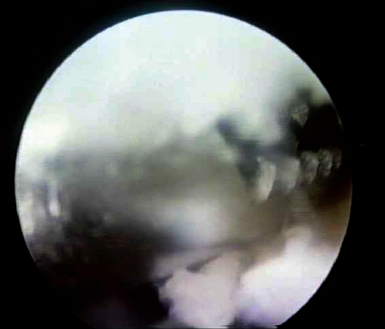

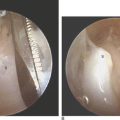

Once an appropriate drill hole is made, a biopsy can be taken of the lesion using a curette or arthroscopic biopsy forceps (Figure 23.9). Usually the cavity is filled with a viscous gelatinous material. Histology should confirm a fibrous capsule of compressed collagen fibers, fibroblasts, and mesenchymal cells around a viscous clear mucinoid center. These features are consistent with an intraosseous ganglion.

A standard 3-mm arthroscopic motorized resector is introduced into the drill hole to enable debridement of the remaining soft tissue (Figures 23.10 and 23.11). Fluoroscopy is used intermittently to confirm position of the instruments during the procedure. To confirm the adequacy of the debridement, the arthroscope can be advanced to view the intraosseous cavity (osteoscopy!). This helps confirm that all soft tissue has been removed.

Bone grafting is performed to restore the normal architecture of the lunate and minimize the risk of lunate collapse. An incision is made over the dorsal aspect of the wrist proximal to Lister’s tubercle. A small cortical window is made in the radius. Cancellous bone is then harvested. A 3-mm bore trocar can then be advanced directly into the hole in the lunate. Fluoroscopy is used to confirm that the trocar is well seated within the debrided lunate. The harvested bone graft is delivered through the trocar and impacted into the lunate by pushing the graft through the trocar using a small tamping rod. This reduces the risk of any graft falling into the wrist joint. The lesion is grafted up to the margin of the cortical bone rather than the articular cartilage. The lunate is finally assessed arthroscopically and fluoroscopically to ensure that the graft is suitably positioned. The joint is thoroughly irrigated prior to the wounds being sutured with an absorbable suture.

Potential Pitfalls

Patient selection is the key to the successful outcome of this procedure. Relief of symptoms in previous reports of curettage and grafting procedures was not uniform or predictable.1,2,5,6 Symptoms appear to correlate uniformly with having a positive bone scan.2 For this reason, patient recruitment should hinge on the presence of a bone scan with heightened activity in our opinion.

It is possible to have an extraosseous extension of the ganglion. Preoperative clinical radiographic and CT are therefore important. Fluoroscopic and arthroscopic assessments are important in this minimal-access technique. The surgeon needs to be familiar with advanced wrist arthroscopic techniques. A volar wrist portal may be required to enable visualization by the arthroscope or to act as a portal to introduce and advance the drill.14 No patient has required a salvage procedure after arthroscopic treatment in the author’s hands.

Results

In our published series there were 10 patients followed for a minimum of three years.7 Following surgery, all patients had significant improvements in pain scores, grip strength, range of motion, and function. These have been represented as modified Green scores, which increased 34 points from 51 to 85 points (p = 0.03) by one year postoperatively.10 The scores were maintained in all patients at last review.

In summary, patients with IOG who were treated with this arthroscopic technique had significant improvements in pain scores and functional activity, which were well maintained. The results compare well with previous reports.1,2,5

1 Tham S, Ireland DC. Intraosseous ganglion cyst of the lunate: Diagnosis and management. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1992;17(4):429-432.

2 Waizenegger M. Intraosseous ganglia of carpal bones. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1993;18–33:350-355.

3 Sullivan PP, Berquist TH. Magnetic resonance imaging of the hand, wrist and forearm: Utility in patients with pain and dysfunction as a result of trauma. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1991;66:1217-1221.

4 Mogan JV, Newberg AH, Davis PH. Intraosseous ganglion of the lunate. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1981;6(1):61-63.

5 Schajowicz F, Clavel Sainz M, Slullitel JA. Juxta-articular bone cysts (intra-osseous ganglia): A clinicopathological study of eighty-eight cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61(1):107-116.

6 Kambolis C, Bullough PG, Jaffe HI. Ganglionic cystic defects of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55(3):496-505.

7 Ashwood N, Bain GI. Arthroscopically assisted treatment of intraosseous ganglions of the lunate: A new technique. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2003;28(1):62-68.

8 Gunther SF. Dorsal wrist pain and the occult scapholunate ganglion. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1985;10(5):697-703.

9 Angelides AC, Wallace PF. The dorsal ganglion of the wrist: Its pathogenesis, gross and microscopic anatomy, and surgical treatment. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1976;1(3):228-235.

10 Green DP, O’Brien ET. Open reduction of carpal dislocations: Indications and operative techniques. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1978;3(3):250-265.

11 Young L, Bartell T, Logan SE. Ganglions of the hand and wrist. Southern Medical Journal. 1988;81(6):697-703.

12 Bain GI, Richards RS, Roth JH. Wrist arthroscopy. In Lichtman DM, Alexander AH, editors: The Wrist and Its Disorders, Second Edition, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1997.

13 Bain GI, Hunt J, Mehta JA. Operative fluoroscopy in hand and upper limb surgery: One hundred cases. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1997;22(5):656-658.

14 Tham S, Coleman S, Gilpin D. An anterior portal for wrist arthroscopy: Anatomical study and case reports. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1999;24(4):445-447.