CHAPTER 21 Arthroscopic Wrist Ganglionectomy

Rationale and Basic Science

Dorsal wrist ganglions are the most common type of soft–tissue swellings that present around the wrist. They usually originate from the dorsal portion of the scapholunate ligament, at or just distal to the dorsal folds of the radiocarpal capsule.1 The dorsal wrist ganglion originates from the scapholunate joint. The cyst pedicle lies at the junction of the dorsal capsule and the distal–most part of the dorsal scapholunate interosseous ligament. From here, the ganglion swells into a sac lying along the dorsal capsule—from where it protrudes as a clinically obvious swelling. The intracapsular portion of the ganglion overlies the scapholunate joint, but the large extra–articular fundus of the cyst may vary in location (although it still remains in close vicinity of the joint).

Wrist arthroscopy offers an excellent view of the wrist joint, and with modern mechanized shavers intra–articular pathology can be effectively debrided. In the case of a ganglion, the intra–articular portion is easy to see because it lies against the dorsal capsule. The pedicle of the ganglion at the scapholunate ligament can be visualized in the majority of cases, and can be resected effectively along with the intra–articular portion with minimal surgical incisions. This may reduce the incidence of recurrence after surgery. In addition, arthroscopy allows a thorough visual examination and palpation by probe of the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints to exclude other sources of wrist pain. The use of wrist arthroscopy to effectively treat dorsal wrist ganglia is not new and was first proposed by Osterman in 1995.2

Clinical Features and Indications

Most ganglia present in females in the second, third, or fourth decades of life. Spontaneous resolution is common but can take several years, with 50% of untreated patients “ganglion free” when assessed at six years.3

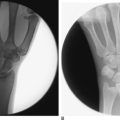

The most common presenting complaint is the cosmetic concern relating to a lump present on the back of the wrist. The other less common complaints are discomfort localized to the area of the swelling or fear of possible malignancy. Although the diagnosis is usually quite obvious in the majority of cases, other causes of wrist pain must be excluded by a thorough clinical examination and routine radiography. The ganglion is a soft cystic swelling that has no inflammatory signs. Transillumination by a penlight and fluctuation are two key clinical signs that demonstrate the clear fluid nature of the lump and exclude other soft–tissue tumors. If the patient seeks absolute confirmation, ultrasound examination is diagnostic. MR imaging is more expensive, but is indicated if Kienbock’s disease is to be excluded.

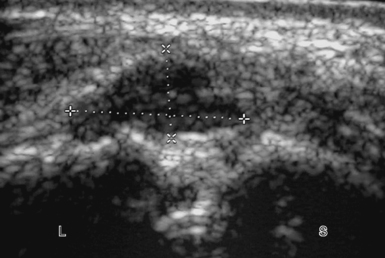

The patient with an occult wrist ganglion will complain of wrist discomfort over the area of the scapholunate joint and may or may not notice intermittent swelling in the area. As the swelling is not visible clinically, confirmation by MR imaging or ultrasound is mandatory. Ultrasound is the most cost effective and will demonstrate the ganglion as a hypoechoic mass overlying the scapholunate joint and deep to the wrist capsule (Figure 21.1).4

Management options include reassurance that the swelling is harmless, and spontaneous resolution is possible if one is prepared to wait for a reasonable length of time. This holds true especially in the pediatric population, where cysts around the wrist are likely to resolve spontaneously in up to 80% of cases.5 A brief period of rest in a splint may help to reduce pain. Needle aspiration does provide immediate symptom relief, with resolution of the swelling, but the reported recurrence rate is about 60%.6,7 The injection of steroid after aspiration does not seem to affect the high recurrence rates, and with risk of subcutaneous atrophy and skin depigmentation is not routinely recommended.8

Surgical Technique

Contrary to traditional wrist arthroscopy that commences on the radial side with initial visualization through the 3–4 portal, for ganglionectomy the author prefers to start from the ulnar side of the wrist from the 6–R portal for the following reasons. Introduction of the scope through the 3–4 portal may actually enter through the ganglion, causing it to rupture and making it less distinct. The intra–articular portion of the ganglion impairs visibility and examination of the joint is not possible. Furthermore, the 3–4 portal will be used for instrumentation to debride the ganglion. The author therefore recommends using the 3–4 portal for diagnostic arthroscopy only after the ganglion has been debrided.

An 18–gauge needle is inserted into the 6–R portal first to localize the level of the ulnocarpal articulation and to ensure that the triangular fibrocartilagenous disc is not violated. A 4–mm transverse incision is made in the skin and a small hemostat is introduced into the joint and spread gently. The blunt trocar and cannula are inserted and then the trocar is exchanged for the scope (Figure 21.2).

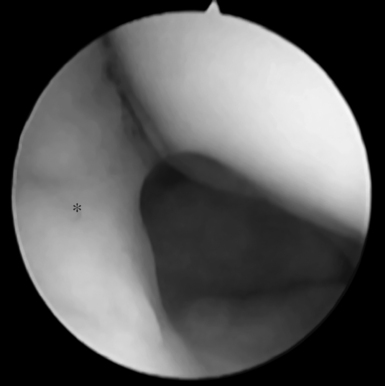

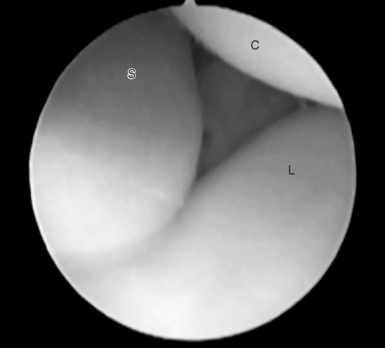

By directing the scope radially, it is possible to see the scapholunate articulation in profile. The ganglion can be seen lying against the dorsal capsule. Tracking the ganglion as the scope is tilted dorsally, the stalk of the ganglion can be seen running to the distal part of the dorsal scapholunate interosseous ligament along the capsular reflection. When the inflow of saline is commenced, the ganglion is compressed against the dorsal capsule and becomes less distinct (Figure 21.3). Fluid outflow may be provided by an 18–gauge needle inserted into the 1–2 portal. This, however, is not always necessary because adequate outflow will be provided during insertion of the shaver.

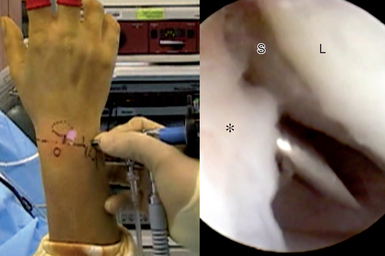

An 18–gauge needle is introduced through the ganglion and into the 3–4 arthroscopic portal. As landmarks may be obscured by the swelling, the portal is made in line with the radial border of the long finger. The needle is inserted into the joint under arthroscopic vision and is directed into the radiocarpal space (Figure 21.4).

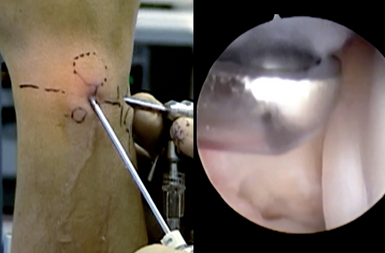

The 3–4 portal is then developed by making a transverse incision through the skin and spreading the capsular entry with a small hemostat. A 2.3–mm full–radius shaver is introduced into the joint and the ganglion is then systematically resected, starting with the capsular portion (Figure 21.5).

Resection requires working at a very steep angle, with the shaver at times almost parallel to the forearm as the surgeon resects the capsular portion of the ganglion. An aggressive shaver may be used for this purpose. The use of the 1–2 portal has been recommended for better visualization and ease of resection.9,10 In the author’s experience, however, this has not been necessary. The author recommends avoiding this portal because of the risk of radial sensory nerve complications.

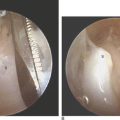

Attention is then turned to the pedicle that runs along the distal capsular reflection to the distal–most part of the dorsal SLIL. Using a nonaggressive shaver angled distally, the pedicle is debrided with gentle pressure against the SLIL. Caution must be exercised when using an aggressive shaver for this purpose because it may disrupt part of the ligament (Figure 21.6).

Some patients may demonstrate additional synovitis along the rim of the dorsal radius. This may be a manifestation of underlying scapholunate instability and needs to be evaluated with a midcarpal arthroscopy.11 The red fragile fronds of synovitis are distinct from the well–localized and avascular ganglion. The synovitis can also be debrided using a shaver, or lesser amounts can be vaporized using a thermal probe. By this time, the intra–articular ganglion is completely debrided, there is a visible defect in the dorsal capsule, and the extra–articular portion of the ganglion should have been decompressed (Figure 21.7).

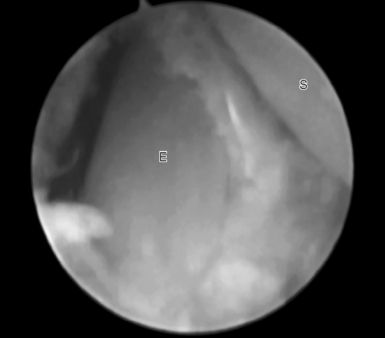

If the external ganglion mass is still tense, the capsular window needs to be widened to allow the ganglion to discharge into the joint. Using an arthroscopic punch forceps, the portal hole in the capsule is widened. This may help to minimize possibilities of recurrence by removal of the one–way “capsular valve” that allows fluid to accumulate in the extra–articular portion of the ganglion.12 Capsular window enlargement is not necessary for the treatment of occult ganglia that are totally intra–articular. Some authors recommend capsular resection only for cases when the ganglion or its stalk is not identifiable through the arthroscope. The author prefers to enlarge the opening using controlled removal of small portions with a forceps, rather than an aggressive shaver, because this method has less risk of injury to the radial wrist extensor tendons (Figure 21.8).

FIGURE 21.8 View from the 6-R portal. Widening of the capsular portal brings the wrist extensor tendon (E) into view.

Once resection is complete, further examination of the radiocarpal joint is performed by inserting the arthroscope through the 3–4 portal. The appearance of articular surfaces is recorded and the integrity of the scapholunate ligament and the triangular fibrocartilage is confirmed with a probe.

Arthroscopic evaluation of the midcarpal joint is essential after resection of the ganglion. It is not uncommon to visualize a minor degree of scapholunate laxity with a step–off at the articulation. Less commonly, the ganglion extends into the midcarpal joint—obscuring visualization through the radial midcarpal portal. An ulnar midcarpal portal is then developed for the scope, and the ganglion is debrided with a shaver introduced through the radial midcarpal portal (Figure 21.9).

Results

The most common concern after surgery for ganglion removal is recurrence, with reported rates from less than 1 to 25% after open surgery. Recurrence rates after arthroscopic ganglionectomy appear to be much lower. Osterman2 did not report any recurrences in 18 cases, whereas Fontes13 reported recurrence in 1 of 32 cases, Luchetti in 2 of 34 cases, and Rizzo in 2 of 42 cases.2,14,15 To prevent recurrence, it is essential to identify and effectively debride the pedicle. If the pedicle is not clearly visualized in the radiocarpal joint, the midcarpal joint must also be examined. A 1–cm section of dorsal capsular cuff must be resected if the pedicle is not well visualized or if the external ganglion remains tense even after the intra–articular portion is debrided.

1 Angelides AC, Wallace PF. The dorsal ganglion of the wrist: Its pathogenesis, gross and microscopic anatomy, and surgical treatment. J Hand Surg. 1976;1(3):228-235.

2 Osterman AL, Raphael J. Arthroscopic resection of dorsal ganglion of the wrist. Hand Clin. 1995;11:7-12.

3 Burke FD, Melikyan EY, Bradley MJ, Dias JJ. Primary care referral protocol for wrist ganglia. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2003;79(932):329-331.

4 Blam O, Bindra R, Middleton W, Gelberman R. The occult dorsal carpal ganglion: Usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound in diagnosis. American Journal of Orthopedics. 1998;27(2):107-110.

5 Wang AA, Hutchinson DT. Longtitudinal observation of pediatric hand and wrist ganglia. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2001;26:599-602.

6 Nield DV, Evans DM. Aspiration of ganglia. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1986;11:264.

7 Richman JA, Gelberman RH, Engber WD, et al. Ganglions of the wrist and digits: Results of treatment by aspiration and cyst wall puncture. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1987;12:1041-1043.

8 Varley GW, Needoff M, Davis TRC, et al. Conservative management of wrist ganglia. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1997;22:636-637.

9 Nishikawa S, Toh S, Miura H, Arai K, Irie T. Arthroscopic diagnosis and treatment of dorsal wrist ganglion. J Hand Surg. 2001;26B:547-549.

10 Luchetti R, Badia A, Alfarano M, Orbay J, Indriago I, Mustapha B. Arthroscopic resection of dorsal wrist ganglia and treatment of recurrences. J Hand Surg. 2000;25B:38-40.

11 Watson HK, Rogers WD, Ashmead DIV. Reevaluation of the cause of the wrist ganglion. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1989;14(5):812-817.

12 Andren L, Eiken O. Arthrographic studies of wrist ganglions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53(2):299-302.

13 Fontes D. Ganglia treated by arthroscopy. In: Saar P, Amadio PC, Foucher G, editors. Current Practice in Hand Surgery. London: Martin Dunitz; 1997:283-290.

14 Pederzini L, Ghinelli, Soragni O. Arthroscopic treatment of dorsal arthrogenic cysts of the wrist. Journal of Sports Traumatology and Related Research. 1995;17:210-215.

15 Rizzo M, Berger RA, Steinmann SP, Bishop AT. Arthroscopic resection in the management of dorsal wrist ganglions: Results with a minimum 2-year follow-up period. J Hand Surg. 2004;29(1):59-62.