CHAPTER 19 Arthroscopic Wrist Capsulotomy

Introduction

Wrist contractures can occur following any type of wrist injury, but are most prevalent following distal radius fractures. Ganglion excision, carpal dislocation or fracture, previous wrist surgery, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and prolonged immobilization may all lead to a loss of wrist motion. Watson has previously described a release of the volar and dorsal wrist capsule through open capsulotomies.1 A similar approach has been described for the distal radioulnar joint.2 Arthroscopic release of wrist contractures has been reported by a number of authors, with encouraging results.3–5

Indications

A biomechanical study performed by Palmer et al. defined functional wrist motion as being flexion of 5 degrees, extension of 30 degrees, radial deviation of 15 degrees, and ulnar deviation of 10 degrees.6 Patients lacking a functional arc of wrist motion who have failed a trial of dynamic/static progressive splinting are candidates for this procedure. Volar capsulotomies are less risky and are indicated to regain wrist extension. Dorsal capsulotomies are necessary to regain wrist flexion but they may require use of a volar arthroscopy portal and are technically more difficult.

Contraindications

Contraindications in this case include all of those general to wrist arthroscopy, including active infection, large capsular tears (which can lead to extravasation of irrigation fluid), bleeding disorders, neurovascular compromise, marked swelling (which distorts the anatomy), inadequate or marginal soft–tissue coverage of the wrist, and the inability to withstand anesthesia. Division of the radioscaphocapitate (RSC), long radiolunate (LRL), and short radiolunate (SRL) ligaments should be performed with caution in patients who are at risk for ulnar translocation (such as those patients with rheumatoid arthritis and those who have undergone previous radial styloidectomies).7,8 A frank carpal volar or dorsal carpal instability pattern is another contraindication because release of the volar and/or dorsal extrinsic ligaments would likely exacerbate this condition.

Surgical Technique

Volar Capsulotomy

The procedure is done under tourniquet control. A 3−/,4 portal and 4−/,5 portal are established as described in Chapter 1. Inflow through the scope with outflow through a cannula in the 6–R portal is standard, although it may be necessary to switch in cases where adhesions block the flow. The radiocarpal joint space is identified with a 22–gauge needle and the joint is inflated with saline. A contracted joint may accept only a small amount of fluid.

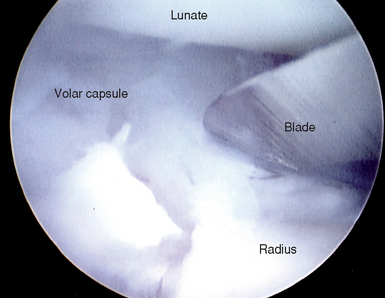

A suction punch and full–radius resector are used to clear adhesions off the volar capsule until the RSC, LRL, radioscapholunate ligament (RSL), and SRL are well defined. While viewing through the 3−/,4 portal, an arthroscopic knife is introduced through a cannula placed in the 4−/,5 portal (Figure 19.1). The cannula is necessary in order to protect the extensor tendons from inadvertent laceration during insertion and removal of the knife. The tip of the blade should be visualized at all times to prevent inadvertent perforation of the capsule or chondral damage. The RSC ligament is gently sectioned until the volar capsular fat and/or the flexor carpi radialis tendon is seen. Anatomical and MRI studies by Verhellen and Bain established that the radial artery was closest to the joint capsule at an average distance of 5.2 mm, the median nerve 6.9 mm, and the ulnar nerve 6.7 mm.5

In order to section the ulnolunate (UL) and ulnolunotriquetral (ULT) ligaments, it is often necessary to establish a 6–R portal because instrumentation and viewing across the radiocarpal joint are often limited due to scarring. The 6–U portal may be used interchangeably for instrumentation. The UL and ULT ligaments should not be released in the presence of a lunotriquetral ligament tear because the combination of these results in a volar intercalated segmental instability pattern in sectioning studies, especially when the dorsal radiocarpal ligament is also released.9

Dorsal Capsulotomy

A blunt trocar and cannula are introduced through the floor of the FCR sheath, which overlies the interligamentous sulcus between the radioscaphocapitate ligament and the long radiolunate ligament. The trocar is again used in a sweeping fashion to clear a path for the arthroscope. The arthroscope is then inserted through the cannula. A hook probe is inserted in the 3−/,4 portal. A suction punch and full–radius resector is exchanged with the probe or inserted through the 1−/,2 portal to clear adhesions until the dorsal capsule and the DRCL are seen. In patients with a partial or complete scapholunate ligament tear, sectioning the DRCL should be done with caution because it may exacerbate any preexisting scapholunate instability.10–12

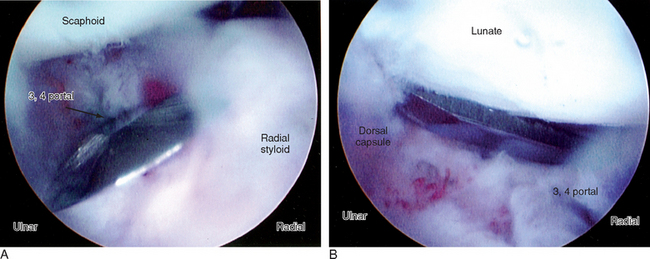

While visualizing through the VR portal, an arthroscopic knife is then introduced through a cannula placed in the 3−/,4 portal (Figure 19.2a and b). The dorsal capsule and the DRCL are gently sectioned until the dorsal capsular fat and/or the extensor tendons can be seen. The wrist should be taken out of traction and the amount of extension assessed. If it is desirable to release the dorsoulnar capsule it is necessary to establish a volar ulnar (VU) portal (see Chapter 1) or to view through the 6–U portal. The adhesions are cleared through use of the 4−/,5 and 6–R portals and then a capsulotomy is performed in a similar fashion.

Postoperative Management

Bleeding may be quite brisk, and hence postoperative hematomas are minimized by the use of a compressive dressing. A below–elbow volar splint may be added for comfort. It is the author’s custom to inject 5 mg of Duramorph into the radiocarpal joint in addition to 0.25% Marcaine infiltration of the portals for postoperative pain management. Excessive bleeding requires insertion of a hemovac drain for the first 24 to 48 hours. Immediate finger motion is instituted. Protected wrist motion is started within the first week, followed by dynamic and/or static progressive wrist flexion and/or extension splinting as soon as the patient’s comfort allows in order to maintain any gains in wrist motion achieved at the time of surgery.

Results

There are few series on arthroscopic release of contracture. Osterman initially advised against releasing the volar capsular ligaments due to the risk of destabilizing the carpus,3 but did not report this complication in a later presentation of the results of combined volar and dorsal capsulotomies.4 Verhellen and Bain reported a series of two patients.5 They performed a release of the RSC, LRL, and SRL but recommended preserving the ULL and ULT ligaments. In light of the evidence from sectioning studies, however, the surgeon should strive to release as few of the volar and dorsal capsular structures as possible in order to achieve the desired result.

1 Watson HK, Dhillon SD. Stiff joints. In: Green DP, Pederson WC, editors. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1993:549-562.

2 Kleinman WB, Graham TJ. The distal radioulnar joint capsule: Clinical anatomy and role in posttraumatic limitation of forearm rotation. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1998;23:588-599.

3 Osterman A. Wrist arthroscopy: Operative procedures. In: Green DP, Pederson WC, editors. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. Fourth Edition. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:207-222.

4 Osterman A, Bednar JM. The Arthroscopic Release of Wrist Contracture. Presented at the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, 55th Annual Meeting. Seattle, WA. October 5–7, 2000.

5 Verhellen R, Bain GI. Arthroscopic capsular release for contracture of the wrist: A new technique. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:106-110.

6 Palmer AK, Werner FW, Murphy D, Glisson R. Functional wrist motion: A biomechanical study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1985;10:39-46.

7 Siegel DB, Gelberman RH. Radial styloidectomy: An anatomical study with special reference to radiocarpal intracapsular ligamentous morphology. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1991;16:40-44.

8 Nakamura T, Cooney WPIII, Lui WH, et al. Radial styloidectomy: A biomechanical study on stability of the wrist joint. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2001;26:85-93.

9 Viegas SF, Patterson RM, Peterson PD, et al. Ulnar-sided perilunate instability: An anatomic and biomechanic study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1990;15:268-278.

10 Viegas SF, Yamaguchi S, Boyd NL, Patterson RM. The dorsal ligaments of the wrist: Anatomy, mechanical properties, and function. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999;24:456-468.

11 Slutsky DJ. Arthroscopic repair of dorsal radiocarpal ligament tears. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:E49.

12 Slutsky DJ. Management of dorsoradiocarpal ligament repairs. Journal of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. 2005;5:167-174.