CHAPTER 11 Arthroscopic Treatment of Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Instability

The shoulder is one of the most versatile joints in the body, allowing a large functional range of motion in multiple planes. This freedom of motion, however, also renders the joint particularly vulnerable to instability. The shoulder is the most commonly dislocated large joint of the body, with an incidence rate of 0.7% for men and 0.3% for women up to the age of 70 years.1 Based on a study of over 2000 individuals, Hovelius2 reported the prevalence of shoulder dislocation to be 1.7%.

Anterior traumatic dislocation is the most common injury pattern and constitutes 96% of all glenohumeral dislocations.3 Unfortunately, management of the primary anterior shoulder dislocation remains a complex and challenging problem for the orthopedic surgeon. The existing literature has provided conflicting evidence regarding the outcomes of nonoperative management versus immediate surgical stabilization, and decision making is further complicated by variables such as patient age, occupation, functional demands, sports participation, physical characteristics, and family history. Whether nonoperative or surgical stabilization is selected, the goal of the treating physician is to achieve a stable, functional shoulder with full restoration and a painless range of motion.

Although specific recurrence rates following anterior shoulder dislocation remain difficult to determine, there are abundant data supporting the fact that following a traumatic dislocation event, the shoulder is more vulnerable to recurrent instability. Young age at the time of the initial injury is the most consistent and significant prognostic factor for a high risk of recurrent instability episodes. Male gender has also been shown to be independently predictive of recurrent instability. The vast majority of recent studies, however, have failed to show a correlation between the participation in or type of sporting activity and the risk of recurrent instability.4–32

With the advent and rapid improvement in arthroscopic shoulder techniques, arthroscopic stabilization has become a viable and frequently used procedure to address anterior instability. Compared with the more traditional open stabilization procedures, arthroscopy has conferred the significant advantages of improved visualization and reduced surgical trauma and perioperative pain, as well as the ability to identify and treat associated intra-articular pathology, such as superior labrum anteroposterior (SLAP) tears or glenoid articular defect (GLAD) lesions. In addition, the need to detach and repair the subscapularis is entirely avoided. Despite these advantages, however, failure rates as high as 50% have been reported in midterm case series.9–11 Although the cause of this failure is likely multifactorial, it is clear that meticulous surgical technique and correction of the pathologic anatomy are essential to maximize the likelihood of success.

PATHOANATOMY

A traumatic glenohumeral dislocation typically results in damage to the bony and/or soft tissue stabilizers of the joint, although the degree and nature of the injury are highly variable. Most patients who sustain a traumatic, anterior dislocation of the shoulder will have an avulsion of the anterior labrum and capsule from the glenoid rim, the classic Bankart lesion, at the time of surgery.4 Because the anterior labrum and attached inferior glenohumeral ligament complex are the major passive anterior stabilizers of the shoulder, the high rate of recurrent instability after dislocation may be attributed to failure of the labrum to heal in an anatomic position. Biomechanical studies, however, have demonstrated that an isolated essential Bankart lesion is insufficient to allow for frank glenohumeral dislocation.5–8 Associated plastic deformation of the glenohumeral ligaments is a prominent factor in recurrent instability and must be addressed if successful stabilization is to be achieved arthroscopically. In addition to reattaching the labrum to the glenoid, an inferior to superior shift of the anterior capsule is necessary, especially in cases of chronic instability.

A variety of other injuries to the osseous and soft tissue stabilizers of the shoulder joint are frequently encountered after anterior dislocation. The Hill-Sachs lesion (compression fracture of the humeral head), fracture of the greater tuberosity, capsular stretch or tears, superior labral lesions, and tears of the rotator cuff are often seen.12–13 Wintzell and colleagues14–18 evaluated a series of 30 patients between the ages of 18 and 30 years with an MRI scan within 3 weeks of the injury and reported an avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments in 20 patients (66%), a pathologic condition of the labrum in 22 patients (73%), and a combined capsulolabral avulsion in 16 patients (53%).

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Multiple studies have confirmed young age to be the most consistent and significant prognostic factor for a higher risk of recurrent instability.19–29 Male gender has also been shown to be independently predictive of recurrent instability. Although conflicting evidence has been reported regarding the correlation of recurrent instability with participation in sporting activities, retrospective series have raised the concern of a potentially increased risk of recurrent dislocation in the athletic population, particularly in those patients participating in shoulder-straining sports.30–32 In Bankart’s original report,4 glenohumeral dislocation was referred to as a condition “peculiar to athletics and epileptics.”

A comprehensive physical examination is essential and begins with the patient sitting. Neck range of motion, Spurling’s, and Adson’s tests should be completed to evaluate for cervical causes of pain or discomfort. Scapulothoracic mechanics and the presence of supraspinatus and/or infraspinatus atrophy should be identified. Primary or secondary scapular winging can present with anterior or posterior instability and must be identified. Significant atrophy may warrant electromyographic studies to evaluate for associated compressive neuropathies or muscular dystrophy. Passive and active glenohumeral range of motion should be assessed. Apprehension in an abducted and externally rotated position is suggestive of anterior instability. Rotator cuff strength and lift-off and belly press tests for subscapularis integrity must be performed. Anterior shoulder dislocations, particularly in older individuals, are frequently accompanied by traumatic rotator cuff tears, which also contribute to pathologic instability. Tests for symptomatic labral pathology should also be performed. Although a myriad of tests have been described, we prefer the active compression (O’Brien’s sign) and resisted supinated external rotation tests.33,34 Both have been validated with good sensitivity and specificity for anterior and superior labral lesions. The presence of multidirectional and generalized ligamentous laxity should also be assessed. We examine for a pathologic sulcus sign in the seated position and also examine for Wynne-Davies criteria (e.g., thumb hyperextension, thumb to forearm testing).35 Laxity alone can be a normal finding and does not equate to instability; however, symptomatic laxity would be manifested by actual instability.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Further imaging studies in the setting of a clear history and physical examination may not be necessary. However, computed tomography (CT) is useful in the setting of recurrent instability in which there is concern for glenoid bone loss. An inverted pear configuration, in which the diameter below the glenoid equator is smaller than that above the equator, has been shown to significantly increase the risk of failure after arthroscopic stabilization.36,37 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also useful to assess for associated intra-articular pathology. MRI can underestimate the degree of bone loss; in difficult cases, three-dimensional CT is more reliable for quantifying bone deficiencies. Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL), although substantially less common than Bankart lesions, can occur following traumatic dislocation and can be detected on coronal images. These lesions are difficult to stabilize arthroscopically and are more reliably addressed via an open repair. Bankart or anterior labrum periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA) injuries are best visualized on axial images and are manifest by extravasation of synovial fluid into a cleft between the labral complex and bony glenoid margin.38, 39 Chondral status, GLAD lesions, rotator cuff integrity, and superior labrum–biceps anchor injury can also be readily assessed on MRI scans.

INDICATIONS

After First-Time Dislocation.

After a first-time dislocation, the risk of recurrence is unacceptably high, usually in the young, male, athletic population. Substantial evidence exists that there is a subset of first-time dislocators who experience a high recurrence rate, with a mean of approximately 67% reported across large series. A number of randomized controlled studies have not only documented a reduced risk of recurrence with early stabilization, but an improved quality of life and durable functional outcome.40–46 The risk for progressive, irreversible intra-articular injury with recurrent instability episodes, which may negatively affect subsequent surgical success rates, may also provide a rationale for early surgical stabilization.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Multidirectional Instability.

This can occur with pathologic laxity and poor glenohumeral ligament quality. Arthroscopic anterior stabilization in this setting has a higher rate of documented recurrence and failure compared with open capsular shift procedures.47

Large Bony Bankart Lesions.

These can lead to an inverted pear configuration48 and are relative contraindications to arthroscopic anterior stabilization. They are often better reduced and rigidly fixed via an open procedure. Although the definition of a large bony fragment is subjective, a 6-mm-wide or larger fragment will typically compromise 25% or more of the articular surface and has been advocated as a relative indication for an open repair.40–47 Note, however, that not all bony Bankart lesions are contraindications to an arthroscopic stabilization. Small lesions can be excised and the capsulolabral complex advanced to the fracture line, or the fragment can be reduced and incorporated into the repair. Favorable results with these techniques have been reported in the literature.51

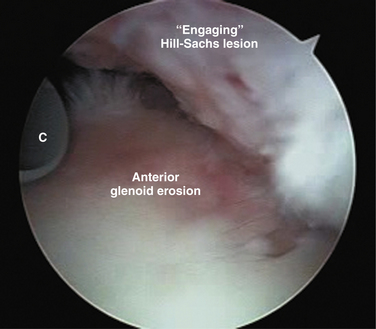

Engaging Hill-Sachs Lesions.

These lesions, more than 30% to 40% of the humeral head, are a relative contraindication to arthroscopic anterior stabilization, particularly in combination with anterior glenoid erosion. Rates of recurrence are considerably reduced with open stabilization.48 Bone grafting of the humeral head defect has been reported to reduce the risk of recurrence. Arthroscopic remplissage, in which the infraspinatus is tenodesed into the Hill-Sachs defect, can be a potentially useful adjunct if anterior stabilization provides stability, but does not completely limit anterior translation.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Conservative Management

Nonoperative management typically involves a period of immobilization for a variable duration after closed reduction, followed by physical therapy for strengthening of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers. The basis for this treatment strategy, however, is largely anecdotal and the literature regarding the efficacy of these interventions is controversial. Aronen and Regan have advocated a program of immobilization followed by intense rehabilitation.49 Twenty military personnel who sustained primary anterior shoulder dislocations were followed for an average of 36 months. All patients participated in an identical treatment regimen, which included a rehabilitation program emphasizing the muscles of internal rotation and adduction, plus rigid restrictions of activities until an asymptomatic stable shoulder was noted. Strength exercises progressed from isometrics to isotonics and isokinetics. The authors reported a success rate of 75%, and concluded that adherence to an aggressive postdislocation rehabilitation program could effectively allow a full return to preinjury activities. There was a 25% recurrence rate, however.

Other studies, however, have failed to corroborate these conclusions. Burkhead and Rockwood50 reported on 140 shoulders that had a diagnosis of traumatic or atraumatic recurrent subluxation and were treated with a specific set of muscle-strengthening exercises. Only 16% of the 74 shoulders that had traumatic subluxation had a good or excellent result from the exercises, compared with 80% of the 66 shoulders that had atraumatic subluxation. Hovelius and associates22,23 have found no correlation between the type or duration of immobilization and the rate of recurrence among 247 patients with primary anterior dislocations who were followed for 10 years. Chalidis and coworkers27 and Kralinger and colleagues32 both reported similar findings, failing to identify any correlation between duration of immobilization and recurrence risk in series of 308 and 241 patients, respectively. Kralinger’s group was also unable to demonstrate any substantial benefit from supervised physical therapy, suggesting that a well-structured home program completed independently by the patient may be equally effective.

Immobilization of the shoulder in external rotation after primary, traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation may be more favorable than conventional sling immobilization to reduce the risk of recurrent instability. MRI studies have demonstrated improved position and coaptation of the Bankart lesion against the glenoid rim with external rotation.52–54 Furthermore, Miller and associates55 conducted biomechanical studies in a human cadaveric model and measured the contact force between the Bankart lesion and the glenoid, with the arm in 60 degrees of internal rotation, neutral rotation, and 45 degrees of external rotation. They reported no contact force with the arm in internal rotation, but the contact force increased as the arm passed through neutral rotation and reached a maximum at 45 degrees of external rotation.

Two randomized clinical trials have provided further evidence that immobilization in external rotation may be beneficial. Itoi and coworkers53,54 presented a series of 40 patients, randomized equally to conventional immobilization in internal rotation versus immobilization in 10 to 30 degrees of external rotation for 3 weeks after the initial dislocation. The recurrence rate was 30% in the internal rotation group and 0% in the external rotation group at a mean of 15.5 months. Recently, a much larger series by the same authors was published,52 reporting 2-year follow-up data on 198 patients with a primary anterior dislocation who were randomized to immobilization in internal rotation or external rotation for 3 weeks. Statistical analysis revealed the recurrence risk to be significantly lower in the external rotation group, with a relative risk reduction of 38.2%. When the analysis was restricted to patients younger than 30 years, the effect was even more profound, with a relative risk reduction of 46.1%.

Surgical Stabilization

Arthroscopic Technique

The lateral decubitus position is the preferred position for anterior stabilization procedures. Care must be taken to ensure complete unencumbered access to the anterior and posterior aspects of the shoulder while the anesthesiologist and equipment are positioned at the foot of the table (Fig. 11-1).

After the joint is entered, dual anterior portals are established at the inferior and superior margins of the rotator interval (Fig. 11-2) using an inside-out technique with a Wissinger rod. The anterior-inferior working portal requires an 8.25-mm cannula to allow for the passage of suture hooks for subsequent repair, and should be created slightly superior to the superolateral border of the subscapularis. Use of a spinal needle to verify a satisfactory angle of approach to the inferior glenoid can be helpful prior to establishing the anterior-inferior working portal. The anterior-superior portal becomes the viewing portal while the posterior portal is converted to a working portal (Fig. 11-3).

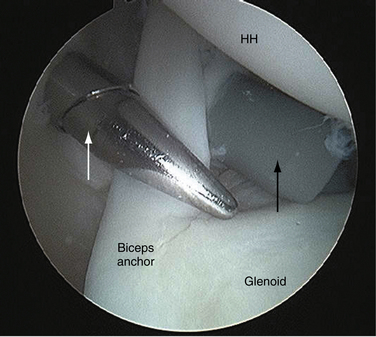

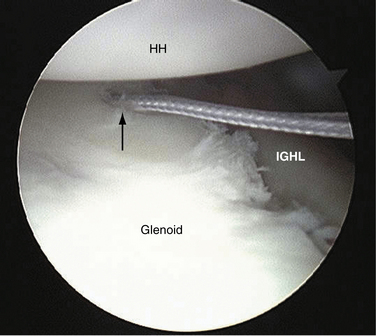

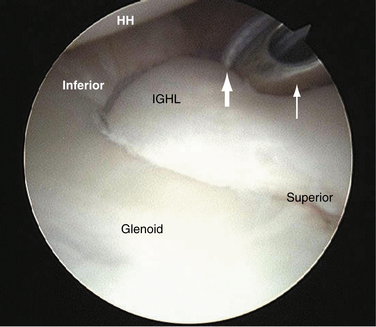

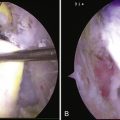

A probe is used via the anterior-inferior portal to complete a comprehensive diagnostic arthroscopy. The inferior capsular pouch and humeral insertion of the ligaments are visualized to confirm the absence of a lesion (Fig. 11-4). If a Hill-Sachs lesion is encountered, the potential for engagement of the humeral head on the anterior glenoid margin should be assessed in the abducted, externally rotated position (Fig. 11-5). If contact occurs, there is concern for potential breakdown of the Bankart repair should this engagement occur postrepair.

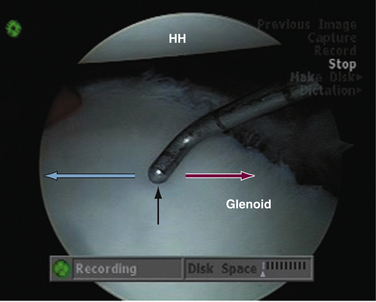

Sufficient glenoid bone stock can be confirmed arthroscopically. Measuring from the bare spot, the presumed center of the glenoid, the radius of the glenoid can be measured on the intact posterior glenoid and the bony deficiency calculated comparing the anterior and posterior radii (Fig. 11-6). Bone loss of more than 20% to 25% may necessitate a bony solution.

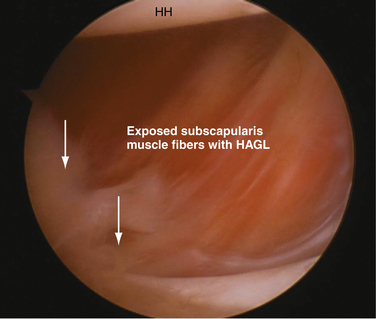

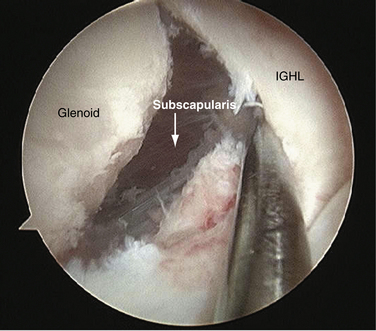

Continuing to view from the anterior-superior portal, attention is now directed toward mobilization of the Bankart lesion. A periosteal elevator or radiofrequency device is used to develop the plane between the glenoid and capsulolabral complex. To retension the inferior glenohumeral ligament adequately, a thorough release must be accomplished so that the defect can be closed and the tissue also can be shifted inferior to superior. The capsulolabral complex is completely freed from the glenoid neck when the subscapularis muscle belly can be clearly visualized (Fig. 11-7).

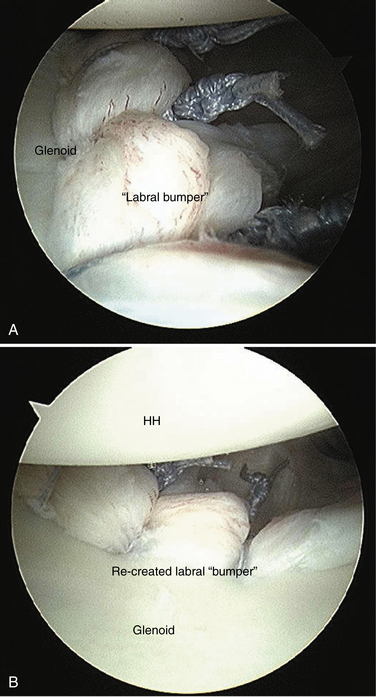

The glenoid neck is prepped with a shaver (burr is rarely needed), and the double-loaded anchors are inserted on to the glenoid face by 1 to 2 mm (Fig. 11-8). Placement on to the glenoid face allows for better bone purchase and facilitates re-creation of the concavity-compression phenomenon, in which the labral bumper is re-established and the glenoid deepened. It is best to approach the glenoid at approximately 45 degrees relative to the articular surface to ensure secure anchor purchase in bone. The position of the first anchor is always guided by the pathology and should be at the level of the inferior aspect of the labral tear. The detached capsulolabral complex should be captured and translated to this anchor to achieve a superior shift of the tissue.

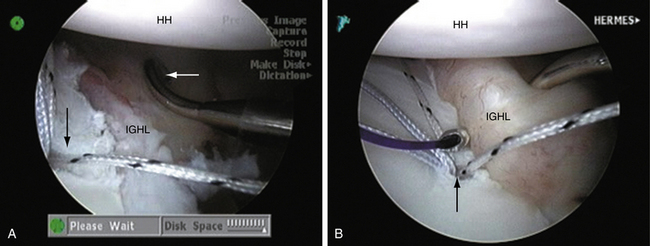

Using a no. 1 absorbable suture loaded into a suture hook directed 45 degrees toward the same side as the involved shoulder (i.e., right hook for a right shoulder), the inferior glenohumeral ligament is penetrated 1 to 2 cm inferior to the anchor. The inferior glenohumeral ligament is then shifted inferior to superior, as well as lateral to medial (Fig. 11-9). The no. 1 absorbable suture is used as a (poor man’s) suture shuttle and, once the actual suture tail is tied to the absorbable suture, the permanent suture is retrograded through the labrum (Fig. 11-10). It should be noted that the suture tail and absorbable shuttle are collected, tied, and then retrograded using the posterior working cannula. For those with associated ligamentous laxity, a plication stitch, in which a portion of the capsule is grasped by the hook prior to passage through the labrum, can be used to decrease capsular volume in addition to repairing the Bankart lesion.

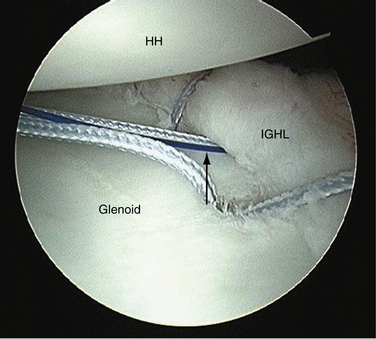

A minimum of three double-loaded anchors should be used. Each suture passage should shift tissue from inferior to superior. When delivering knots, the limb that passes through the labrum (capsule) should serve as the post so that the knot is prevented from resting adjacent to the articular surface and so that the labrum is pushed on to the glenoid face, re-creating labral height (Fig. 11-11). At the completion of the repair, the anterior labral bumper should be visible (Fig. 11-12).

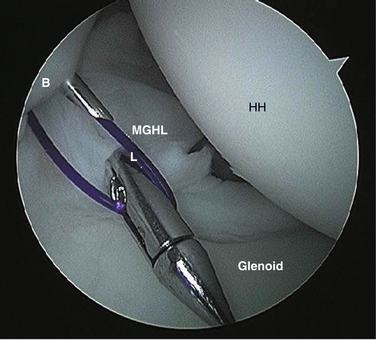

If a patulous interval is noted on completion of the Bankart repair, a rotator interval closure can be performed. A straight suture hook loaded with a no. 1 absorbable suture is passed through the superiormost portion of the rotator interval tissue via the anterior-inferior portal. A straight or angled tissue penetrator is then also placed via the anterior-inferior portal and passed through the middle glenohumeral ligament. The absorbable suture is retrieved, the arm is positioned in neutral rotation, and the suture is tied blindly in an extracapsular fashion (Fig. 11-13).

PEARLS&PITFALLS

SUMMARY

The management of anterior shoulder instability remains a complex and challenging problem. Treatment must be individualized based on consideration of several patient characteristics, including age, gender, occupation, functional demands, sports participation, physical characteristics, compliance, and expectations. With the advent of and rapid improvement in arthroscopic shoulder techniques, arthroscopic stabilization has become a reliable and frequently used procedure to address anterior instability. Meticulous attention to patient selection and surgical technique is critical to restore the anatomy and function of the capsulolabral complex and to minimize the likelihood of recurrence.

1. Simonet WT, Melton LJ3rd, Cofield RH, Ilstrup DM Incidence of anterior shoulder dislocation in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Orthop Relat Res (186); 1984:186-191.

2. Hovelius L Incidence of shoulder dislocation in Sweden. Clin Orthop Relat Res (166); 1982:127-131.

3. Goss TP. Anterior glenohumeral instability. Orthopedics. 1988;11:87-95.

4. Bankart ASB. Recurrent or habitual dislocation of the shoulder joint. Br Med J. 1923;2:1132-1133.

5. Apreleva M, Hasselman CT, Debski RE, et al. A dynamic analysis of glenohumeral motion after simulated capsulolabral injury. A cadaver model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:474-480.

6. Pouliart N, Marmor S, Gagey O Simulated capsulolabral lesion in cadavers: dislocation does not result from a Bankart lesion only. Arthroscopy, 22; 2006:748-754.

7. Pouliart N, Gagey O. The effect of isolated labrum resection on shoulder stability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:301-308.

8. Speer KP, Deng X, Borrero S, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of a simulated Bankart lesion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:1819-1826.

9. Geiger D, Herley J, Tovey J, Rao JP Results of arthroscopic versus open Bankart suture repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (337); 1997:111-117.

10. Grana WA, Buckley PD, Yates CK. Arthroscopic Bankart suture repair. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:348-353.

11. Walch G, Boileau P, Levigne C, et al Arthroscopic stabilization for recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation: Results of 59 cases. Arthroscopy, 1; 1995:173-179.

12. Calandra JJ, Baker CL, Uribe J. The incidence of Hill-Sachs lesions in initial anterior shoulder dislocations. Arthroscopy. 1989;5:254-257.

13. DePalma AF, Flannery GF. Acute anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1973;1:6-15.

14. Wintzell G, Hovelius L, Wikblad L, et al Arthroscopic lavage speeds reduction in effusion in the glenohumeral joint after primary anterior shoulder dislocation: a controlled randomized ultrasound study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 8; 2000:56-60.

15. Wintzell G, Haglund-Akerlind Y, Nowak J, Larsson S Arthroscopic lavage compared with nonoperative treatment for traumatic primary anterior shoulder dislocation: a 2-year follow-up of a prospective randomized study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 8; 1999:399-402.

16. Wintzell G, Haglund-Akerlind Y, Ekelund A, et al. Arthroscopic lavage reduced the recurrence rate following primary anterior shoulder dislocation. A randomised multicentre study with 1-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7:192-196.

17. Wintzell G, Haglund-Akerlind Y, Tengvar M, et al. MRI examination of the glenohumeral joint after traumatic primary anterior dislocation. A descriptive evaluation of the acute lesion and at 6-month follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1996;4:232-236.

18. Wintzell G, Haglund-Akerlind Y, Tidermark J, et al A prospective controlled randomized study of arthroscopic lavage in acute primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder: one-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 4; 1996:43-47.

19. Rowe CR. Acute and recurrent dislocations of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44:998-1008.

20. Rowe CR. Prognosis in dislocations of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1956;38:957-977.

21. Rowe CR, Sakellarides HT. Factors related to recurrences of anterior dislocations of the shoulder. Clin Orthop. 1961;20:40-48.

22. Hovelius L, Augustini BG, Fredin H, et al. Primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder in young patients. A ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1677-1684.

23. Hovelius L. Anterior dislocation of the shoulder in teen-agers and young adults. Five-year prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:393-399.

24. Arciero RA, Taylor DC. Primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder in young patients. A ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:299-300.

25. Arciero RA, Taylor DC, Snyder RJ, Uhorchak JM Arthroscopic bioabsorbable tack stabilization of initial anterior shoulder dislocations: a preliminary report. Arthroscopy, 11; 1995:410-447.

26. Arciero RA, Wheeler JH, Ryan JB, McBride JT. Arthroscopic Bankart repair versus nonoperative treatment for acute, initial anterior shoulder dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:589-594.

27. Chalidis B, Sachinis N, Dimitriou C, et al. Has the management of shoulder dislocation changed over time. Int Orthop. 2007;31:385-389.

28. Cofield RH, Simonet WT. The shoulder in sports. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:157-164.

29. Simonet WT, Cofield RH. Prognosis in anterior shoulder dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:19-24.

30. Henry JH, Genung JA. Natural history of glenohumeral dislocation—revisited. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10:135-137.

31. te Slaa RL, Wijffels MP, Brand R, Marti RK. The prognosis following acute primary glenohumeral dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2004;86:58-64.

32. Kralinger FS, Golser K, Wischatta R, et al. Predicting recurrence after primary anterior shoulder dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:116-120.

33. Myers TH, Zemanovic JR, Andrews JR The resisted supination external rotation test: a new test for the diagnosis of superior labral anterior posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med, 33; 2005:1315-1320.

34. O’Brien SJ, Pagnani MJ, Fealy S, et al The active compression test: a new and effective test for diagnosing labral tears and acromioclavicular joint abnormality. Am J Sports Med, 26; 1998:610-613.

35. Wynne-Davies R Acetabular dysplasia and familial joint laxity: two etiological factors in congenital dislocation of the hip. A review of 589 patients and their families. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 52; 1970:704-716.

36. Sahajpal DT, Zuckerman JD. Chronic glenohumeral dislocation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg.. 2008 Jul;16:385-398.

37. Griffith JF, Antonio GE, Yung PS, et al Prevalence, pattern, and spectrum of glenoid bone loss in anterior shoulder dislocation: CT analysis of 218 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 190; 2008:1247-1254.

38. Connell DA, Potter HG, Wickiewicz TL, et al. Noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging of superior labral lesions. 102 cases confirmed at arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:208-213.

39. Bui-Mansfield LT, Taylor DC, Uhorchak JM, Tenuta JJ Humeral avulsions of the glenohumeral ligament: imaging features and a review of the literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 179; 2002:649-655.

40. Arciero RA, Wheeler JH, Ryan JB, McBride JT. Arthroscopic Bankart repair versus nonoperative treatment for acute, initial anterior shoulder dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:589-594.

41. Kirkley A, Werstine R, Ratjek A, Griffin S Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of immediate arthroscopic stabilization versus immobilization and rehabilitation in first traumatic anterior dislocations of the shoulder: long-term evaluation. Arthroscopy, 21; 2005:55-63.

42. Edmonds G, Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Fowler PJ. The effect of early arthroscopic stabilization compared to nonsurgical treatment on proprioception after primary traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:116-121.

43. Kirkley A, Griffin S, Richards C, et al. Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of immediate arthroscopic stabilization versus immobilization and rehabilitation in first traumatic anterior dislocations of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:507-514.

44. Kirkley A, Griffin S, McLintock H, Ng L. The development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for shoulder instability. The Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI). Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:764-772.

45. Kirkley S. Primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder in young patients. A ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:300-301.

46. Jakobsen BW, Johannsen HV, Suder P, Søjbjerg JO Primary repair versus conservative treatment of first-time traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder: a randomized study with 10-year follow-up. Arthroscopy, 23; 2007:118-123.

47. Meehan RE, Petersen SA. Results and factors affecting outcome of revision surgery for shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:31-37.

48. Burkhart SS, De Beer JF Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy, 16; 2000:677-694.

49. Aronen JG, Regan K. Decreasing the incidence of recurrence of first time anterior shoulder dislocations with rehabilitation. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:283-291.

50. Burkhead WZJr, Rockwood CAJr. Treatment of instability of the shoulder with an exercise program. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:890-896.

51. Sugaya H, Yoshiaki K, Akihiro T Arthroscopic bony Bankart repair: Results of at least one-year follow-up. Arthroscopy, 28; 2003:211-215.

52. Itoi E, Hatakeyama Y, Sato T, et al. Immobilization in external rotation after shoulder dislocation reduces the risk of recurrence. A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2124-2131.

53. Itoi E, Hatakeyama Y, Kido T, et al A new method of immobilization after traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder: a preliminary study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 12; 2003:413-415.

54. Itoi E, Sashi R, Minagawa H, et al. Position of immobilization after dislocation of the glenohumeral joint. A study with use of magnetic resonance imaging. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:661-667.

55. Miller BS, Sonnabend DH, Hatrick C, et al. Should acute anterior dislocations of the shoulder be immobilized in external rotation? A cadaveric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:589-592.