CHAPTER 28 Arthroscopic Treatment of Trapeziometacarpal Disease

Introduction

There are myriad techniques for open treatment of trapeziometacarpal (TM) osteoarthritis (OA). These have included partial and complete trapezium excision with or without ligament reconstruction and with or without interposition of tendon, fascia lata, gortex, artelon, or silicone. Instances of reactive synovitis have tempered the enthusiasm for interposition of foreign substances. Recent reports in the North American literature1,2 of good results following complete trapeziectomy with hematoma arthroplasty have rejuvenated interest in this technique, which has been commonplace in Europe for some time.3 Arthroscopic techniques for evaluating and treating trapeziometacarpal disease surfaced in 1994.4,5

The question of whether to interpose tendon is still a matter of debate. Proponents of the hematoma arthroplasty cite data that demonstrates no advantages in terms of pinch strength, thumb motion, and pain relief following an arthroplasty with tendon interposition compared to an isolated trapeziectomy.6 The hematoma arthroplasty relies on the development of a stable pseudarthrosis that develops from the ingrowth of fibrous tissue, which replaces the blood that immediately fills the cavity following an excision of the trapezium. Pinning the thumb metacarpal base to the index for five to six weeks is integral to the procedure, but augmentation or reconstruction of the TM joint capsule is not. The good results that have been obtained with open trapeziectomy have provided the impetus for the development of arthroscopic techniques.

The scaphotrapezotrapezoidal (STT) joint is also commonly affected by OA. The STT fusion popularized by Watson has largely fallen out of favor. As an alternative to this, distal scaphoid resection has been shown to provide good symptomatic relief.7

Indications

Littler and Eaton described a radiographic staging classification of TM OA.8 Stage I comprises normal articular surfaces without joint space narrowing or sclerosis. There is less than 1/3 subluxation of the metacarpal base. Stage II reveals mild joint space narrowing, mild sclerosis, or osteophytes < 2 mm in diameter. Instability is evident on stress views, with > 1/3 subluxation. The STT joint is normal. In stage III there is significant joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and peripheral osteophytes > 2 mm in diameter (but a normal STT joint).

In stage IV there is pantrapezial OA with narrowing, sclerosis, and osteophytes involving both the TM and STT joints. Burton modified this classification by incorporating the clinical findings.9 Stage I includes ligamentous laxity and pain with forceful and/or repetitive pinching. The joint is hypermobile, which can be seen on stress views (but X-rays are normal). In stage II, crepitus and instability can be demonstrated clinically—whereas X-rays reveal a loss of the joint space. Stages III and IV are similar to Eaton’s classification. Patients in stage I (and possibly early stage II) are appropriate candidates for arthroscopic debridement and capsular shrinkage.10

Badia proposed a more specific classification based on arthroscopic changes.11 Stage I included intact articular cartilage, stage II included eburnation on the ulnar 1/3 of the metacarpal base and central trapezium, stage III comprised widespread full-thickness cartilage loss on both surfaces. Based on intraoperative findings, he recommended debridement for stage I, with thermal capsulorrhaphy in the presence of dorsal subluxation, extension/abduction osteotomy of the metacarpal base ∀ thermal shrinkage for stage II, and an arthroscopic interposition arthroplasty for stage III. He recommended an open arthroplasty in the presence of associated severe STT joint OA.

As a general rule, any patient who is an appropriate candidate for a hemiresection arthroplasty of the TM joint would also be suitable for an arthroscopic hemitrapeziectomy. This would typically include patients in stage II and stage III with unremitting pain despite appropriate conservative measures. This form of treatment does not preclude an open trapeziectomy and/or ligament reconstruction at a later date as a salvage procedure for failed arthroscopic surgery. The presence of Eaton stage IV disease is a relative contraindication to a hemitrapeziectomy, although an arthroscopic hemitrapeziectomy combined with an arthroscopic debridement or limited resection of the distal scaphoid is an option. The rationale for this would be similar to that of the double interposition arthroplasty described by Eaton and Barron, in which the TM and STT joints are resurfaced while the body of the trapezium is left intact in order to prevent a loss of height of the thumb ray.12 Failing this, a complete arthroscopic (or open) trapeziectomy would be necessary.

Precautions

Any significant lateral subluxation of the thumb metacarpal base will not be corrected without some type of ligament reconstruction or capsular shrinkage, and may compromise the long-term result if not corrected. Metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint hyperextension must be treated concomitantly. Otherwise, the reconstruction may ultimately fail. MP hyperextension of 10 to 20 degrees may be treated by percutaneous fixation of the MP joint in flexion for four to six weeks, and/or transfer of the extensor pollicis brevis to the thumb metacarpal base. MP hyperextension of 20 to 40 degrees can be addressed with a volar plate advancement13 or capsulodesis.14 A sesamoidesis MP hyperextension > 40 degrees is typically controlled by an MP fusion.

Contraindications

This would include any general contraindication to thumb arthroscopy, including distortion of the anatomy due to swelling, unstable or friable skin (which would preclude the use of traction), and recent infection. Ehler Danlos syndrome is a relative contraindication for this procedure, although a successful arthroscopic tendon arthroplasty has been reported.15

Surgical Technique

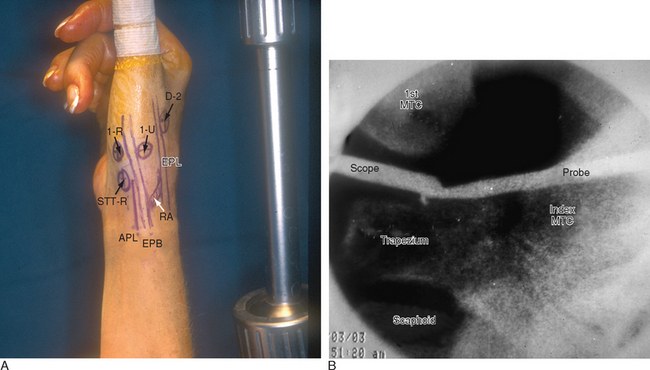

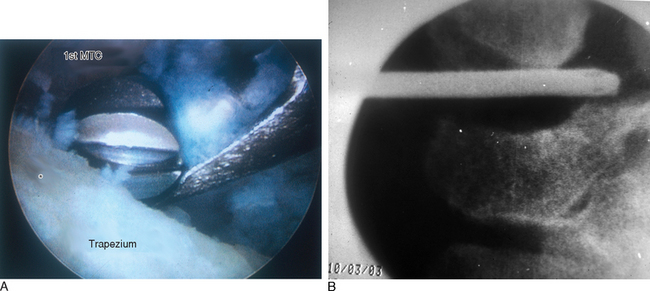

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table, with the arm extended on a hand table. The thumb is suspended by Chinese finger traps with 5 pounds of countertraction, which forces the wrist into ulnar deviation. The relevant landmarks are outlined, including the proximal and dorsal edge of the thumb metacarpal base, the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus (APL), the extensor pollicis longus (EPL), and the radial artery in the snuffbox (Figure 28.1). The procedure is performed with a tourniquet elevated to 250 mmHg. Saline inflow irrigation is provided through the arthroscope and a small- joint pump or pressure bag.

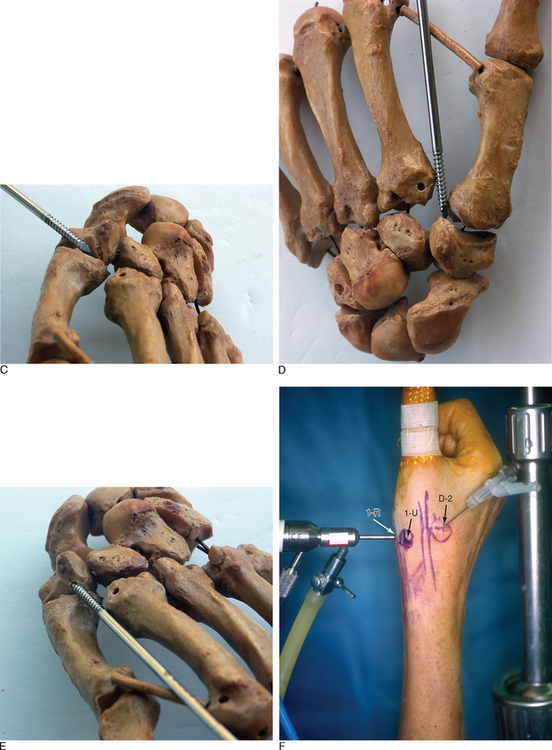

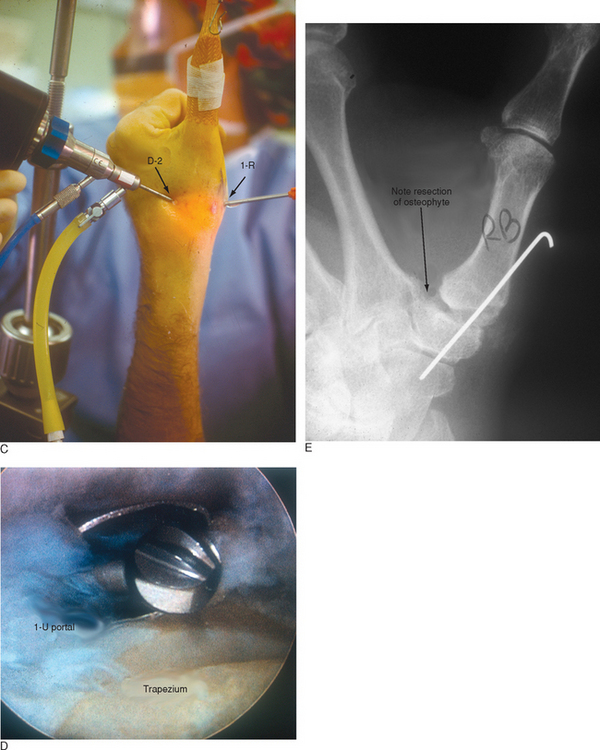

Access to medial trapezial osteophytes may sometimes be difficult. Hence, the author has found the use of a distal/dorsal (D-2) accessory portal to be of some value.16 Its main utility is that it allows one to look down on the trapezium rather than across it, which facilitates resection of medial osteophytes (Figure 28.2a through e). This accessory portal allows views of the dorsal capsule with rotation of the scope and facilitates triangulation of the instrumentation. It is situated in the dorsal aspect of the first web space. An anatomical study of five cadaver hands revealed that the D-2 portal surface landmark is ulnar to the EPL tendon and 1 cm distal to V-shaped cleft at the juncture of the index and thumb metacarpal bases.

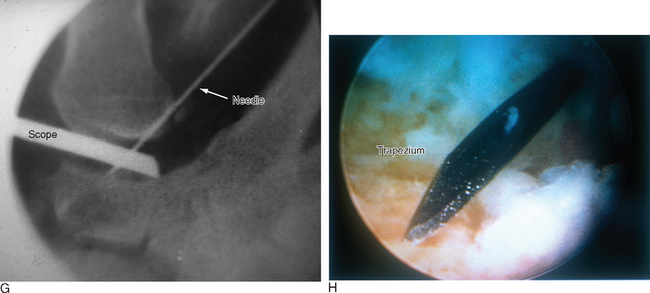

The portal lies just distal to the dorsal intermetacarpal ligament (DIML). To establish the D-2 portal, the intersection of the base of the index and thumb metacarpal is identified just distal and ulnar to the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon. The course of the radial artery is outlined by palpation or Doppler with the tourniquet down. A 22-gauge needle is inserted 1 cm distal to this juncture and angled in a proximal, radial, and palmar direction—hugging the thumb metacarpal while viewing from either the 1-R or 1-U portal (Figure 28.2f through h).A small skin incision is made, and tenotomy scissors are used to spread the soft tissue and pierce the joint capsule. This is followed by insertion of a blunt trocar and cannula and then the arthroscope or alternatively a hook probe, motorized shaver, or 2.9-mm bur.

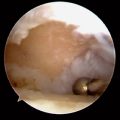

Arthroscopic Partial or Complete Trapeziectomy Without Tendon Interposition

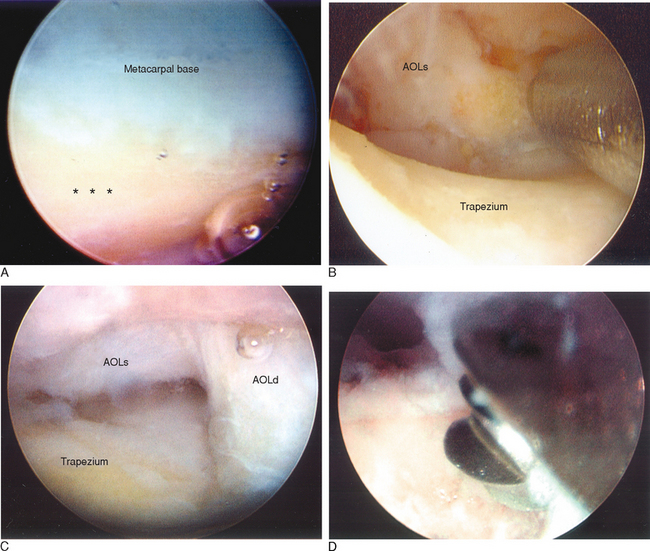

The 1-R and 1-U portals are established as described. The anterior oblique ligament (AOL) is identified and preserved. After joint debridement, a 2.9-mm bur is applied in a to-and-fro manner to resect the distal trapezium (Figure 28.3a through d). The diameter of the bur along with fluoroscopy provides a gauge as to the amount of bony resection. A larger bur may be substituted as the space between the metacarpal base and distal trapezium enlarges. It is crucial to remove any medial osteophytes, which will lead to impingement and possibly to persistent pain.

The D-2 portal is useful for this step because it allows one to debride the medial trapezium from above rather than from across the joint (Figure 28.4a). Culp recommends resecting at least half the distal trapezium,10 although it is my experience that excising 4 to 5 mm is sufficient—provided that all of the medial osteophytes are removed (Figure 28.4b). After the bony resection is complete, the thumb is K-wired in a pronated and abducted position. If there is lateral subluxation of the metacarpal base, thermal shrinkage of the volar oblique ligament can be performed at this time (Figure 28.5a through i).

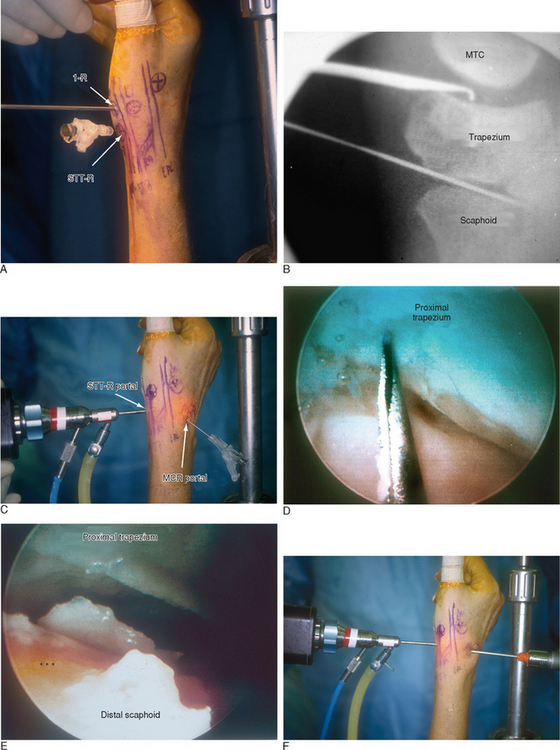

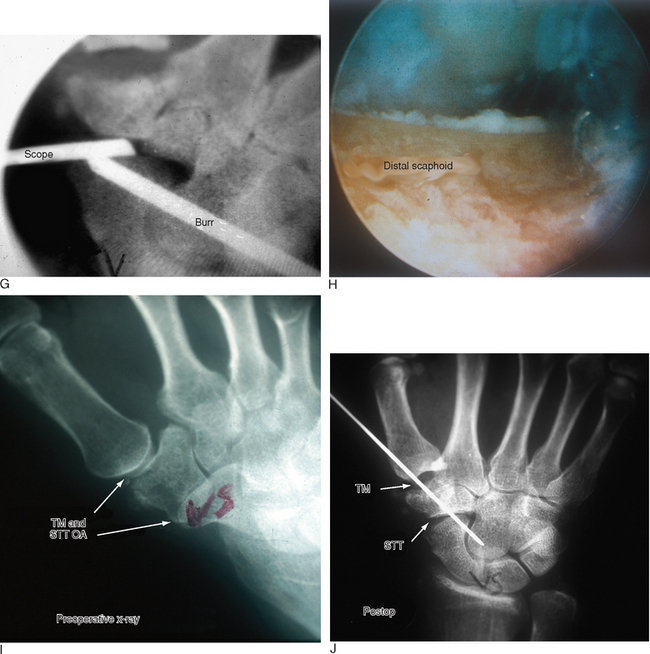

Arthroscopic Distal Scaphoid Resection

If there is significant STT OA, the joint can be debrided as described by Ashwood and Bains.16 Alternatively, a minimal arthroscopic resection of the distal scaphoid can be performed. The STT joint can be viewed through the midcarpal radial portal (MCR) with the bur in the STT-U portal or STT-R portal (Figure 28.6a through j). The portals are likewise interchangeable. The volar and radial scaphotrapezial ligaments are preserved and the bony resection is confined to 2 to 4 mm to lessen the risk of a dorsal intercalated segmental instability (DISI) pattern.

Results

Menon reported his results on performing a partial arthroscopic resection of the trapezium and an interposition arthroplasty in 31 patients (33 hands).4 The mean age was 59 years (range 48 to 81 years), with an average follow-up of 37.6 months (range 24 to 48 months). Gortex was used in 19 patients and autogenous tendon or allograft in 14. Complete pain relief was obtained in 25 patients/hands (75.7%). Three patients had mild pain (four hands), and four patients had persistent pain that required conversion to an open trapeziectomy and ligament reconstruction. All patients maintained their preoperative motion. Pinch strength improved from 6 psi preoperatively to 11.1 psi postoperatively. Because of osteolysis in three patients (four hands), the use of Gortex as an interpositional substance was not recommended.

Culp and Rekant performed a partial or complete arthroscopic trapeziectomy in 22 patients (24 thumbs) with electrothermal shrinkage.10 Detailed data is not available, but they reported 88% excellent or good outcome scores at a follow-up of 1.2 to 4 years. Subsidence of the thumb metacarpal was 2 to 4 mm, and pinch strength improved by 22%.

There are no clinical series on arthroscopic distal scaphoid resection at this time. Arthroscopic debridement of the scaphotrapezial joint without distal resection, however, has been shown to be beneficial.17 There is always the worry that a distal scaphoid resection will worsen any preexisting scapholunate instability by weakening the scaphotrapezial ligaments. In a series of 21 patients who were treated with an open distal scaphoid resection, Garcia-Elias et al. demonstrated the alleviation of pain and discomfort in all cases.7

1 Kuhns CA, Emerson ET, Meals RA. Hematoma and distraction arthroplasty for thumb basal joint osteoarthritis: A prospective, single-surgeon study including outcomes measures. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2003;28:381-389.

2 Jones NF, Maser BM. Treatment of arthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint with trapeziectomy and hematoma arthroplasty. Hand Clin. 2001;17:237-243.

3 Gervis WH. Excision of the trapezium for osteoarthritis of the trapezio-metacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1949;31B:537-539.

4 Menon J. Arthroscopic management of trapeziometacarpal joint arthritis of the thumb. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:581-587.

5 Menon J. Arthroscopic evaluation of the first carpometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1998;23:757.

6 Davis TR, Brady O, Dias JJ. Excision of the trapezium for osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint: A study of the benefit of ligament reconstruction or tendon interposition. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2004;29:1069-1077.

7 Garcia-Elias M, Lluch AL, Farreres A, Castillo F, Saffar P. Resection of the distal scaphoid for scaphotrapeziotrapezoid osteoarthritis. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1999;24:448-452.

8 Eaton RG, Littler JW. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1655-1666.

9 Burton RI. Basal joint arthrosis of the thumb. Orthop Clin North Am. 1973;4:347-348.

10 Culp RW, Rekant MS. The role of arthroscopy in evaluating and treating trapeziometacarpal disease. Hand Clin. 2001;17:315-319. x–xi.

11 Badia A. Trapeziometacarpal arthroscopy: A classification and treatment algorithm. Hand Clin. 2006;22:153-163.

12 Barron OA, Eaton RG. Save the trapezium: Double interposition arthroplasty for the treatment of stage IV disease of the basal joint. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1998;23:196-204.

13 Eaton RG, Floyd WEIII. Thumb metacarpophalangeal capsulodesis: An adjunct procedure to basal joint arthroplasty for collapse deformity of the first ray. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1988;13:449-453.

14 Kessler I. A simplified technique to correct hyperextension deformity of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:903-905.

15 Badia A, Riano F, Young LC. Bilateral arthroscopic tendon interposition arthroplasty of the thumb carpometacarpal joint in a patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: A case report. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:673-676.

16 Slutsky DJ. Use of the D-Z portal in trapeziometarpal arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. In press 2007.

17 Ashwood N, Bain GI, Fogg Q. Results of arthroscopic debridement for isolated scaphotrapeziotrapezoid arthritis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2003;28:729-732.