CHAPTER 8 Arthroscopic Treatment of Scapholunate Ligament Tears

Introduction

Scapholunate interosseous ligament (SLIL) injuries are one of the most common causes of mechanical wrist pain. Despite an increased knowledge of carpal injuries and improvements in radiologic evaluation, the diagnosis of an SLIL tear can be difficult or missed unless the evaluating physician has a high index of suspicion and an appropriate level of understanding of wrist anatomy and injury patterns. Usually a detailed history, physical examination, and a series of plain radiographs are sufficient to make a diagnosis of SLIL injury (Figure 8.1). Occasionally, advanced imaging (such as MRI with or without intra-articular contrast) can be helpful in establishing a diagnosis and evaluating the wrist for associated injuries.1–3 However, MRI usually detects large complete tears better than partial smaller tears, particularly if the tear configuration is oblique to the imaging plane or the tear is smaller than the distance between contiguous image slices.

After successful introduction in the knee and shoulder, arthroscopy gained popularity as one of the most useful modalities for diagnosing and treating a wide spectrum of wrist pathology.4,5 This procedure has become the gold standard for diagnosis of SLIL injuries.6–8 Arthroscopy is a minimally invasive procedure allowing direct observation of intrinsic and extrinsic carpal ligaments as well as articular cartilage integrity under static and dynamic conditions. Therefore, comprehensive and accurate diagnosis and treatment of all carpal injuries can be performed concurrently.

Because a delayed or missed diagnosis of an SLIL tear can lead to progressive carpal instability and predispose the patient to a predictable pattern of carpal arthritis called scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC),9–11 we believe that wrist arthroscopy should be considered early during the evaluation and management of a patient with a suspected SLIL injury. However, it should be used selectively for patients with significant symptoms (a mechanism of injury consistent with SLIL injury) and in whom conservative treatment has failed or for whom acute operative management is indicated.

Anatomy of the Scapholunate Complex

The wrist is a complex structure comprised of multiple small-joint articulations with stability resulting from a complex linkage of intrinsic intercarpal ligaments and extrinsic capsular ligaments. The wrist can be thought of as 2 separate rows—with hand motion being the composite effect of motion among the radius, ulna, proximal carpal row (scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum) and distal carpal row (scaphoid, trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate). Thus, the scaphoid is uniquely situated in both rows on an oblique axis to stabilize the carpus while still permitting coordinated relative motion between the two rows and the radius and ulna. The scaphoid is stabilized by many ligaments, including the SLIL, radioscaphocapitate, scaphotrapeziotrapezoid, scaphocapitate, and dorsal intercarpal ligament.12

The SLIL is a C-shaped structure connecting the dorsal, proximal, and palmar surfaces between the scaphoid and the lunate—leaving the distal aspect of the joint bare of soft tissue and allowing the evaluation of scapholunate articular congruity, preservation, and instability. This midcarpal visualization is essential in assessing the degree of instability between the two bones and in grading the spectrum of partial to complete injury.13 The dorsal and palmar portions of the SLIL are true ligamentous structures.14 The proximal portion is a membranous structure composed mainly of fibrocartilaginous tissue.

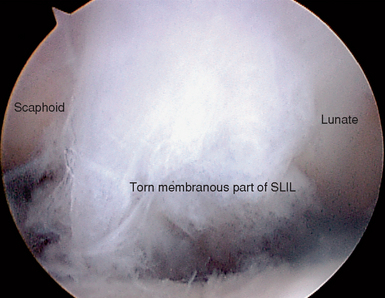

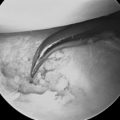

In the absence of a tear, the transition between the dorsal and proximal portions is not readily visualized during arthroscopy. However, palpation of the SLIL with a probe permits differentiation between the thick taut dorsal ligament and the softer thin proximal portion. A partial SLIL tear may appear as a patulous convex outpouching rather than as a confluent (barely discernible) structure (Figure 8.2). Furthermore, the probe may uncover a complete disruption of the insertion of the SLIL—often from the lunate, which could not be perceived with observation alone. Partial tears may require palpation in the radiocarpal joint with a probe (to appreciate the laxity) and a thorough evaluation of the distal scapholunate joint articular surface congruity in the midcarpal joint to observe subtle incongruity or diastasis. A significant complete intrasubstance SLIL tear will be readily visualized in both the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints.

Biomechanical and Kinematics Considerations

The three different portions of the SLIL have different biomechanical properties. The dorsal portion of the SLIL has highest load at ultimate failure, followed by the palmar portion, and then the proximal portion.15 Serial sequential ligament sectioning studies in cadavers have found that the SLIL is the primary ligament scapholunate stabilizer.16–21 However, no significant dissociation between the scaphoid and the lunate is shown on static radiographs with an isolated complete SLIL disruption.16,22 This is explained by the presence of secondary stabilizers of the SL joint, which must be injured either acutely or chronically to demonstrate radiographic instability. Injury to the volar extrinsic (radiolunate, radioscaphocapitate),16,23 distal intrinsic (scaphotrapezial),16,24 or dorsal intercarpal ligament and the SLIL is needed to radiographically visualize pathologic carpal bone rotation.25

Changes in the radiocarpal, intercarpal, and midcarpal joint contact areas and loads in conjunction with the altered kinematics result in predictable SLAC arthritis. This begins with radial styloid beaking and radial styloid-scaphoid joint narrowing (stage 1), which then progresses proximally to alter the radial scaphoid facet proximal pole scaphoid articulation (stage 2) and then the midcarpal capitolunate joint (stage 3).9

Treatment Options

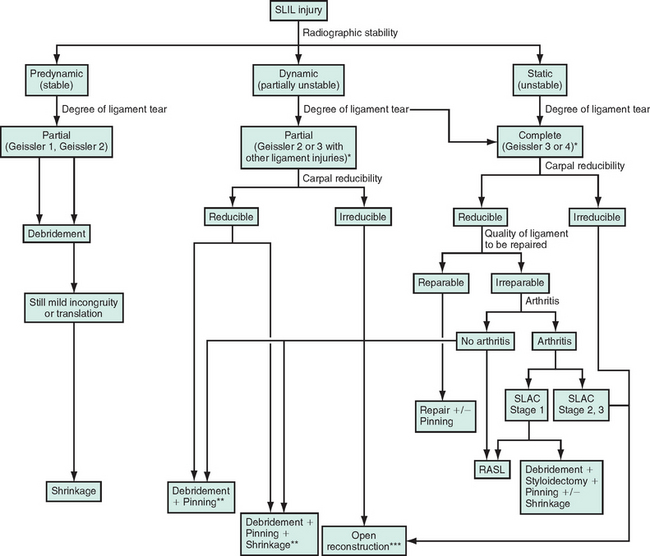

Several factors need to be considered to aid the clinical judgment indicating an arthroscopic procedure, not only to diagnose but to treat symptomatic scapholunate injuries (Figure 8.3). Acute repairable lesions have heretofore been treated with open suture repair or reattachment with bone anchors. Previous reports have sought to separate acute injuries from chronic by using an arbitrary and unproven 6 weeks as a cutoff, with the implied understanding that only acute injuries could be repaired. However, because the patient history is often unreliable as to the first subtle injury versus the most recent and now symptomatic injury dates alone should not indicate irreparable ligaments.

Stable wrists with symptomatic tears (pre-dynamic radiographic instability) are assumed after obtaining normal static and stress radiographs. Unstable wrists with tears demonstrable on grip films or cineradiography only (dynamic radiographic instability) have abnormal carpal alignment on stress radiographs (for example, pronated posterior-anterior grip) but normal alignment on unloaded routine radiographs. Unstable wrists with static instability on routine plain films (static radiographic instability) are the injuries that are obvious and thus not missed. However, these wrists may have advancing cartilage degeneration that is often underappreciated (especially at the capitolunate joint). The presence of significant polyarticular arthritis changes treatment options and often precludes reconstruction and indicates salvage procedures that usually fall outside the purview of arthroscopy (save for the master arthroscopist).

Arthroscopic assessment guides and rationalizes the potential for repair by confirming the degree of injury and the severity of instability.13 Arthroscopic treatment options include the following, either in isolation or in combination: ligament debridement, ligament thermal shrinkage, transarticular Kirschner wire fixation, and radial styloidectomy (Figure 8.3).

Complete repairable tears in the senior author’s (MPR) experience are best managed with open techniques. If the dorsal ligament has been avulsed from its attachment, it can and should be primarily repaired either with transosseous suture or suture anchor. Depending on the amount of associated soft-tissue injuries, this can be augmented with any of the numerous variations on dorsal capsulodesis.26–28

SLAC wrist evolution beyond the radial styloid and scaphoid wrist articulation often requires more extensive open surgical procedures. Complete irreparable tears in a young and active patient with a wide scapholunate diastasis and significant carpal mal-rotation should be considered for any procedure that can realign the carpus and preserve carpal kinematics so that the natural history of end-stage SLAC wrist can be forestalled. One such procedure used by the senior author since 1989 is the reduction and association of the scaphoid and lunate (RASL), creating an SLIL neoligament and protecting the repair with a transosseous SL headless bone screw.

Arthroscopic Debridement

Indications

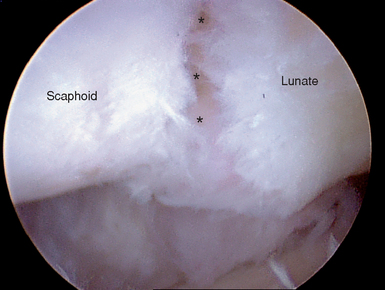

Arthroscopic debridement alone is indicated for acute or chronic partial but stable tears of the volar or membranous portion of the ligament in a patient with mechanical symptoms (Figure 8.4). These patients usually have focal reproducible mechanical wrist pain over the dorsal scapholunate joint worsened by activity and normal X-rays. It is common to treat these patients conservatively for several months with splints and activity modification. Persistent symptoms often lead to an MRI, which rarely provides a definitive diagnosis and certainly does not illuminate the treatment options.

Contraindication to Debridement Alone

An absolute contraindication is a complete reparable tear or a more advanced Geissler instability pattern that was underappreciated in the preoperative evaluation. Static instability patterns with preexistent arthritis will not be helped save in a few selected cases of elderly patients with relatively low demand. A staged debridement and synovectomy can be offered with the full understanding that it may fail and necessitate a more comprehensive salvage procedure.

Results

Isolated arthroscopic debridement has been reported in several small case series (Table 8.1).5,7,29 Most patients have predynamic or dynamic radiographic instability and Geissler grade 1 or 2 tears. Good pain relief, grip strength improvement, and maintenance of range of motion have been reported. The need for postoperative immobilization is unclear because some studies treated patients in a soft dressing with immediate motion and some studies reported wrist immobilization for 6 to 8 weeks.

Radiofrequency Thermal Collagen Shrinkage

Technique

One study describes thermal stabilization using monopolar cautery (Oratec, Mountain View, CA) placed through the 4-5 portal.30 The probe is applied to the SLIL, starting volarly and working dorsally until all lax and redundant SLIL has been made taut. The authors recommend continuous irrigation with a safety limit on the probe set to 75° C to prevent chondral thermal injury. When midcarpal examination reveals the scapholunate joint congruency without gapping, the thermal shrinkage is complete. The authors believe postoperative immobilization for 4 to 6 weeks is critical to allow ligament healing and to prevent recurrent laxity.

Another study uses a 2.3-mm bipolar probe (Vapr; Mitek, Westwood, MA) placed through the 4-5 portal.31 The probe is carefully applied to the torn rim of the volar portion of the ligament, the proximal membranous, and a small part of the dorsal ligament using multiple strokes (like a paintbrush) until visual color changes occur. The probe is used intermittently, delivering energy for only a few seconds at a time to allow adequate outflow of warmed fluid. The tissue quality is palpated with a probe to confirm decreased laxity.

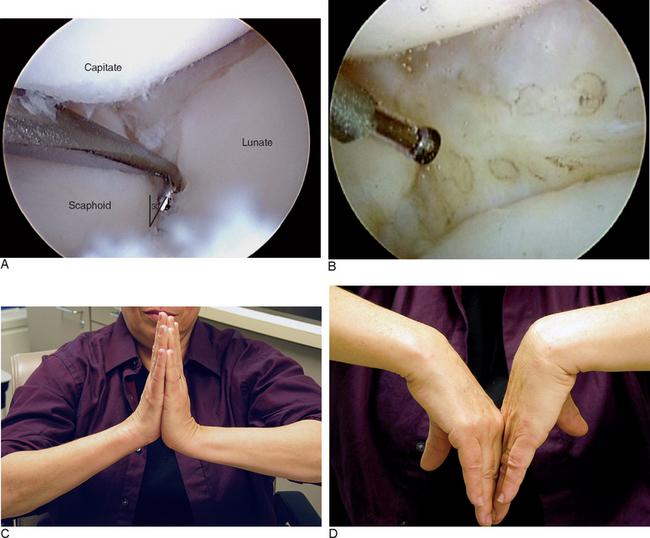

The senior author (MPR) often applies the radiofrequency probe (Microblator 30 1.4-mm, Arthrocare, Sunnyvale, CA) to the proximal membranous portion of the SLIL and to the palmar midcarpal ligaments. In the midcarpal joint, the palmar ligamentous tissue at the junction of the scaphoid and lunate corresponds to the distal edge of the palmar SLIL and the radioscaphocapitate ligament (Figure 8.5).

Results

There are two published series of 10 and 16 patients treated with monopolar and bipolar electrothermal collagen shrinkage and postoperative immobilization ranging from two to six weeks (Table 8.1).30,31 Complete pain relief ranged from 50 to 90%, with preservation of wrist motion and no postoperative radiographic instability.

Arthroscopic-Assisted Temporary Transarticular Wire Placement

Technique

The lunate joystick wire is placed obliquely from proximal-dorsal to distal-palmar so that proximal to distal pressure results in lunate flexion. After the bones have been derotated, a percutaneous wire is placed across the scapholunate joint from radial to ulnar. Either 0.045- or 0.062-inch wires can be used. Pin insertion technique is critical because the anatomic snuffbox contains the dorsal branch of the radial artery, the cephalic vein, and multiple sensory nerve branches with a narrow safe zone.32 Thus, wires should be pushed through the skin and down to the scaphoid-free hand. Then the wire driver is placed over the wire and turned on. By having the wire tip fixed to the bone prior to wire rotation by the driver, soft-tissue injury is minimized. Several divergent pins can be placed across the scapholunate and scaphocapitate joint in this manner. This is the best way to maintain the reduction of the scapholunate diastasis achieved through derotation.

Results

Two case series have been reported on patients who underwent arthroscopic reduction of the scapholunate joint and temporary transarticular scapholunate joint fixation for isolated SLIL injury or associated with a distal radius fracture (Table 8.1).33,34 It should be noted that these types of injuries are very different and do not act the same way clinically over long-term follow-up. Acute injuries recognized and treated following trauma have more predictable outcomes in contradistinction to chronic injuries with a vague history of significant antecedent trauma. This correlates with the quality of the tissue at the ligamentocapsular injury site and its capacity to heal.

Arthroscopic Debridement, Thermal Shrinkage, and Temporary Transarticular Pinning

Contraindications

This procedure is contraindicated and inadequate for patients with static carpal malalignment. This corresponds to chronicity, which translates to a lack of adequate residual ligament as scaffolding that could foster repair and provide stability and improved carpal kinematics. These patients require supplemental tissue grafting utilizing open or closed techniques (such as capsulodeses in their many variations, as well as ligament reconstruction with tendon grafts or bone ligament bone constructs or salvage procedures that restrict carpal motion and maintain reduction through limited intercarpal fusions as scaphotrapezialtrapezoid). Simple debridement and Kirschner pinning for these static instabilities routinely fail to maintain the correction of carpal alignment achieved at surgery.26,35,36

Results

To date there are no published reports detailing the outcomes of patients treated with this protocol. Thus, this communication is the opinion of the senior author (who has performed thermal ligament shrinkage in eight patients with follow-up to an early clinical result). The patients averaged 38.3 years (range 21 to 54) (Table 8.1), and all met the clinical and radiographic inclusion criteria discussed previously. Procedures included eight ligament debridement—four scaphocapitate and four scapholunate transarticular pinning (0.045-inch K-wire)—one dorsal ganglionectomy, two debridement of the triangular fibrocartilage complex, and one posterior interosseous neurectomy. Predynamic and dynamic radiographic instability were observed in five and three patients, respectively.

Reduction and Association of the Scaphoid and Lunate (RASL)

The RASL procedure was developed as an open reconstructive procedure to reassociate the scapholunate joint and foster a fibrous neoligament by dechondrification of the interface and maintaining the reduction through healing with a headless bone screw placed transarticularly by the senior author (MPR). The procedure can be (and is being) done arthroscopically, and although the follow-up is shorter the results are similar.38–40

Indications

The planned retention of a headless bone screw (Figure 8.6) augments and protects the fibrous neoligament while undergoing an expected lucency around the lunate screw threads because it permits near physiologic motion between the scaphoid and lunate. This concept has been confirmed by a cadaveric biomechanical study in which scapholunate motion after the RASL procedure was found to be preserved within 5 degrees of the preinjury state for all positions of wrist motion.41

Technique: Open RASL

The radial styloid is approached through a separate, short, longitudinal radially based incision. Identification and protection of the superficial radial sensory nerve branches and the radial artery are mandatory. Next, the first dorsal compartment retinaculum is incised and reflected and is later used to imbricate the radial collateral ligament and capsule at closure. The thumb tendons are retracted and the capsule is opened longitudinally. A limited styloidectomy is performed, preserving the scaphoid fossa and most of the radioscaphocapitate ligament origin. This provides access to the radial proximal scaphoid for later screw placement and treats the concomitant radio-stylo-scaphoid arthritis. The dorsal capsulotomy is performed through two transverse windows that respect the dorsal intercarpal ligament, an important secondary stabilizer of the wrist.

Then the wire for the cannulated Headless Bone Screw (Orthosurgical Implants, Inc., Miami, FL) is inserted through the radial incision just proximal to the scaphoid waist toward the lunate vertex. The wire should pass through the center of the scaphoid and lunate in both the coronal and sagittal planes to establish an isometric rotation point that will nearly restore carpal kinematics. The depth should be measured so that the screw can be countersunk slightly within the scaphoid. The screw is advanced, and fluoroscopy is used to confirm appropriate screw position and length. The K-wires are all removed. Interrupted absorbable sutures are used to close the radial capsule. The first dorsal retinaculum is closed over the relocated tendons. The dorsal wrist capsule is carefully repaired without imbrication, and no capsulodesis is performed to limit motion. The extensor pollicis longus remains transposed from its sheath.

1 Morley J, Bidwell J, Bransby-Zachary M. A comparison of the findings of wrist arthroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging in the investigation of wrist pain. J Hand Surg [Br]. 2001;26:544-546.

2 Haims AH, Schweitzer ME, Morrison WB, Deely D, Lange RC, Osterman AL, et al. Internal derangement of the wrist: Indirect MR arthrography versus unenhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 2003;227:701-707.

3 Schmitt R, Christopoulos G, Meier R, Coblenz G, Frohner S, Lanz U, et al. Direct MR arthrography of the wrist in comparison with arthroscopy: A prospective study on 125 patients. Rofo. 2003;175:911-919.

4 Rettig ME, Amadio PC. Wrist arthroscopy: Indications and clinical applications. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1994;19:774-777.

5 Ruch DS, Poehling GG. Arthroscopic management of partial scapholunate and lunotriquetral injuries of the wrist. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1996;21:412-417.

6 Dautel G, Goudot B, Merle M. Arthroscopic diagnosis of scapho-lunate instability in the absence of X-ray abnormalities. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1993;18:213-218.

7 Westkaemper JG, Mitsionis G, Giannakopoulos PN, Sotereanos DG. Wrist arthroscopy for the treatment of ligament and triangular fibrocartilage complex injuries. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:479-483.

8 Sennwald G. Diagnostic arthroscopy: Indications and interpretation of findings. J Hand Surg [Br]. 2001;26:241-246.

9 Watson HK, Ballet FL. The SLAC wrist: Scapholunate advanced collapse pattern of degenerative arthritis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1984;9:358-365.

10 Watson HK, Weinzweig J, Zeppieri J. The natural progression of scaphoid instability. Hand Clin. 1997;13:39-49.

11 Taleisnik J. Current concepts review: Carpal instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:1262-1268.

12 Berger RA. The anatomy of the ligaments of the wrist and distal radioulnar joints. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;383:32-40.

13 Geissler WB, Freeland AE, Savoie FH, McIntyre LW, Whipple TL. Intracarpal soft-tissue lesions associated with an intra-articular fracture of the distal end of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:357-365.

14 Berger RA. The gross and histologic anatomy of the scapholunate interosseous ligament. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1996;21:170-178.

15 Berger RA, Imeada T, Berglund L, An KN. Constraint and material properties of the subregions of the scapholunate interosseous ligament. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999;24:953-962.

16 Short WH, Werner FW, Green JK, Masaoka S. Biomechanical evaluation of ligamentous stabilizers of the scaphoid and lunate. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2002;27:991-1002.

17 Burgess RC. The effect of rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid on radio-scaphoid contact. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1987;12:771-774.

18 Ruch DS, Smith BP. Arthroscopic and open management of dynamic scaphoid instability. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;32:233-240. vii

19 Short WH, Werner FW, Green JK, Weiner MM, Masaoka S. The effect of sectioning the dorsal radiocarpal ligament and insertion of a pressure sensor into the radiocarpal joint on scaphoid and lunate kinematics. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2002;27:68-76.

20 Meade TD, Schneider LH, Cherry K. Radiographic analysis of selective ligament sectioning at the carpal scaphoid: A cadaver study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1990;15:855-862.

21 Blevens AD, Light TR, Jablonsky WS, Smith DG, Patwardhan AG, Guay ME, et al. Radiocarpal articular contact characteristics with scaphoid instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1989;14:781-790.

22 Berger RA, Blair WF, Crowninshield RD, Flatt AE. The scapholunate ligament. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1982;7:87-91.

23 Ruby LK, An KN, Linscheid RL, Cooney WPIII, Chao EY. The effect of scapholunate ligament section on scapholunate motion. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1987;12:767-771.

24 Boabighi A, Kuhlmann JN, Kenesi C. The distal ligamentous complex of the scaphoid and the scapho-lunate ligament: An anatomic, histological and biomechanical study. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1993;18:65-69.

25 Mitsuyasu H, Patterson RM, Shah MA, Buford WL, Iwamoto Y, Viegas SF. The role of the dorsal intercarpal ligament in dynamic and static scapholunate instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2004;29:279-288.

26 Szabo RM, Slater RRJr., Palumbo CF, Gerlach T. Dorsal intercarpal ligament capsulodesis for chronic, static scapholunate dissociation: Clinical results. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2002;27:978-984.

27 Wintman BI, Gelberman RH, Katz JN. Dynamic scapholunate instability: Results of operative treatment with dorsal capsulodesis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1995;20:971-979.

28 Lavernia CJ, Cohen MS, Taleisnik J. Treatment of scapholunate dissociation by ligamentous repair and capsulodesis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1992;17:354-359.

29 Weiss AP, Sachar K, Glowacki KA. Arthroscopic debridement alone for intercarpal ligament tears. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1997;22:344-349.

30 Hirsh L, Sodha S, Bozentka D, Monaghan B, Steinberg D, Beredjiklian PK. Arthroscopic electrothermal collagen shrinkage for symptomatic laxity of the scapholunate interosseous ligament. J Hand Surg [Br]. 2005;31(4):458-459.

31 Darlis NA, Weiser RW, Sotereanos DG. Partial scapholunate ligament injuries treated with arthroscopic debridement and thermal shrinkage. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:908-914.

32 Steinberg BD, Plancher KD, Idler RS. Percutaneous Kirschner wire fixation through the snuff box: An anatomic study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1995;20:57-62.

33 Whipple TL. The role of arthroscopy in the treatment of scapholunate instability. Hand Clin. 1995;11:37-40.

34 Peicha G, Seibert F, Fellinger M, Grechenig W. Midterm results of arthroscopic treatment of scapholunate ligament lesions associated with intra-articular distal radius fractures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7:327-333.

35 Wyrick JD, Youse BD, Kiefhaber TR. Scapholunate ligament repair and capsulodesis for the treatment of static scapholunate dissociation. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1998;23:776-780.

36 Muermans S, De Smet L, Van Ransbeeck H. Blatt dorsal capsulodesis for scapholunate instability. Acta Orthop Belg. 1999;65:434-439.

37 Yao J, Osterman AL. Arthroscopic techniques for wrist arthritis (radial styloidectomy and proximal pole hamate excisions). Hand Clin. 2005;21:519-526.

38 Lipton CB, Ugwonali OF, Sarwahi V, Chao JD, Rosenwasser MP. Reduction and association of the scaphoid and lunate for scapholunate ligament injuries (RASL). Atlas of the Hand Clinics. 2003;8:249-260.

39 Rosenwasser MP, Miyasaka KC, Strauch RJ. The RASL procedure: Reduction and association of the scaphoid and lunate using the Herbert screw. Techniques in Hand and Upper Extremity Surgery. 1997;1:263-272.

40 Lipton C, Ugwonali O, Sarwahi V, Chao JD, Rosenwasser MP. The treatment of chronic scapholunate dissociation with reduction and association of the scaphoid and lunate (RASL). Atlas of the Hand Clinics. 2003;8:95-105.

41 Amin, F, Gardner, TR, Ko, BH, Grafe, MW, Raizman, NM, Rosenwasser MP. The RASL procedure (reduction and association of the scaphoid and lunate using the Herbert screw): An evaluation of inter-carpal kinematics in cadaveric wrists. Presented as a paper at the American Association for Hand Surgery Meeting, Tucson, Arizona, January 2006.