CHAPTER 20 Arthroscopic Synovectomy and Abrasion Chondroplasty of the Wrist

Introduction: Rationale and Basic Science

The wrist is a crucial anatomical link between the hand and forearm, with multiple articular surfaces. When it is afflicted by arthritis and conditions that limit motion, it greatly affects the lives of our patients. The advent of arthroscopy has revolutionized the practice of orthopedic surgery, as well as the practice of hand surgery. Many pioneers have contributed newer techniques, and they have fueled the significant growth in wrist and small–joint arthroscopy.1,2

Wrist arthroscopy has provided a means of examining and treating intra–articular abnormalities. Early reports on arthroscopic wrist synovectomy have noted reduced pain, reduced swelling, and improvement of joint function.3–6 The effects, either transitory or permanent, depend mainly on the activities of the patient and the underlying cause of arthritis. Abrasion chondroplasty of the wrist has not been described at length, but what is known is that in canine models “repair cartilage” (fibrocartilage) is formed in place of articular cartilage.7 Excitingly, abrasion chondroplasty appears to have a role specifically in the treatment of patients with proximal pole hamate arthrosis as well as radiocarpal arthrosis. Preliminary results of this method of treatment have been excellent.8–10 This chapter discusses the indications and techniques for arthroscopic synovectomy and abrasion chondroplasty.

Indications

Arthroscopic synovectomy is an effective modality for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile arthritis (JRA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and postinfectious arthritis.3–5 Patients who have developed post–traumatic joint contractures and patients with persistent septic arthritis of the wrist despite systemic antibiotics and lavage benefit from arthroscopic synovectomy as well. In the rheumatoid patient, we follow the protocol established by Adolfsson et al.5 We treat those patients who present with radiographic changes of grades 0 through II (and who have failed to respond to pharmacologic treatment and who have a persistent joint synovitis for more than six months) according to the staging system by Larsen, Dale, and Eek.4,11 In nonrheumatoid patients, the radiographic classification system used to evaluate the progression of the disease is the Outerbridge classification system (originally developed for chondromalacia patellae).12

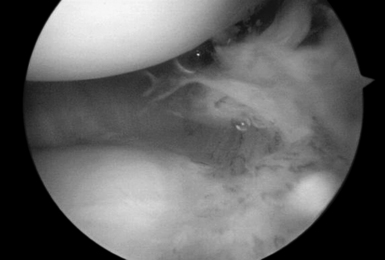

Those patients with early presentation of SLE or reactive arthritis (bacterial or viral), and those patients with osteoarthritis with nominal radiographic changes and florid synovitis, are also considered candidates for wrist synovectomy. Furthermore, those patients who have sustained intra–articular fractures of the distal radius or who have undergone multiple previous wrist interventions also benefit from capsular release, removal of adhesions, and synovectomy (Figure 20.1).

Abrasion chondroplasty is very effective in patients with proximal pole hamate arthritis, specifically those patients with type II lunates (Figure 20.2). This condition causes ulnar–sided pain that occurs when those patients load their wrists in ulnar deviation. When the arthrosis in this area is advanced with exposure of subchondral bone (Outerbridge grade IV), we follow the recommendation of Yao et al. and proceed with an excision of the proximal pole.13 The lunate morphology plays a key role in this condition.

FIGURE 20.2 (A) Plain radiograph AP of a type II lunate. (B) MRI of type II lunate with proximal pole arthrosis.

The type II lunate and its medial facet can lead to arthritis with contact loading of the proximal pole of the hamate. This has been reported in up to 44% of type II lunates versus 2% in type I lunates.9,13–19 Patients with this condition may also have concomitant wrist pathology that can be treated simultaneously, such as triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) tears, lunotriquetral interosseous ligament (LTIL) tear (i.e., hamate arthrosis lunotriquetral ligament tear, or HALT),9 ulnar impaction, and radial–sided, pathology. The presence of a TFCC injury can almost be assured when synovitis along the ulnar side of the wrist is seen during arthroscopy in the absence of any other structural problem.

Radiographic Evaluation

The radiographic evaluation system of Larsen et al. is used for staging the wrist arthritis. We have found that along with an appropriate clinical history dedicated MRI coils and special imaging sequences of the articular cartilage improve the sensitivity and specificity of these studies for detecting chondral defects. This has been a great tool for correlating the clinical and expected arthroscopic findings. Others do not share this viewpoint. In a study of 41 indirect MR arthrograms and 45 unenhanced (nonarthrographic) MR images that were compared to the arthrographic findings, Haims et al. concluded that MRI of the wrist is not adequately sensitive nor accurate in the diagnosis of cartilage defects in the distal radius, scaphoid, lunate, or triquetrum.20

MRI is, however, a good predictor of cases of synovitis and ulnar–sided pathology. Arthroscopic abrasion arthroplasty, subchondral drilling, and microfracture can be performed for the treatment of focal chondral defects in patients with moderate degenerative wrist arthritis or when plain radiographs are suggestive of avascular necrosis. The MRI has been shown to be a sensitive modality that may be used to exclude avascular necrosis as well as to evaluate the extent to which fibrocartilaginous repair tissue has formed postoperatively. This has been demonstrated in the knee, and we have incorporated an MRI evaluation as a part of our postoperative protocol.20,21

Surgical Technique

The arthroscopic synovectomy can be carried out under general or regional anesthesia with the forearm suspended in a traction tower device with finger traps. We tend to use the long and index finger, but in rheumatoid patients with delicate skin it is often recommended that one should place all of the digits in the finger traps to distribute the traction load. Ten to 15 pounds of traction is used. Passive infusion of saline solution is accomplished by gravity traction through a separate inflow cannula or through the scope itself. A 2.7–mm 30–degree arthroscope is inserted through our working portals (which are the 3–, 4, 4–, 5, and 6–R portals for the radiocarpal joint). Outflow is through the 6–U portal. The radial and ulnar midcarpal portals are used to access the midcarpal joint (Figure 20.3).

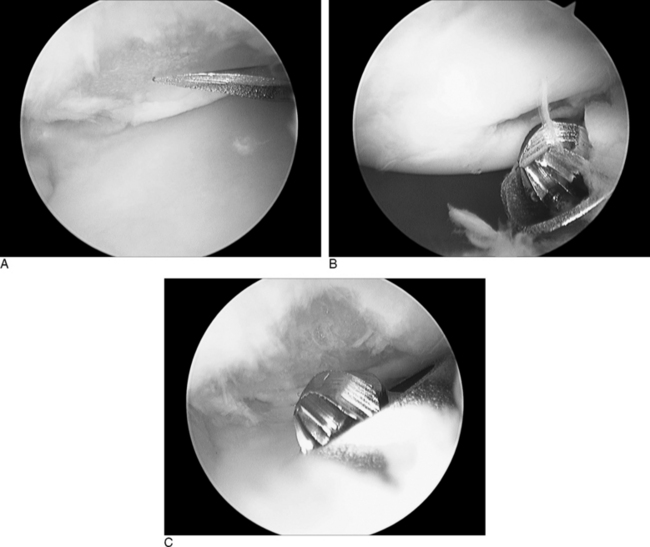

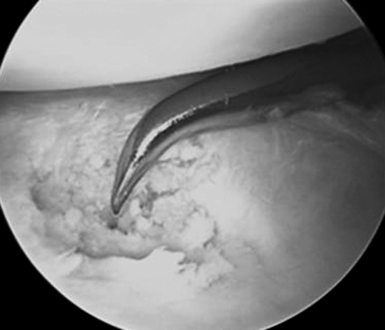

Efficiency and speed are important to minimize wrist swelling. In cases with severe scaphotrapeziotrapezoidal (STT) joint arthritis, a separate portal can be established. All of the inflamed synovial tissue is removed using a motorized shaver system with a 3.5–mm synovial resector blade and 3.5–mm flexible shaver. We have also had good results with the use of thermal ablation, which also decreases bleeding (Figure 20.4). It is essential to maintain adequate irrigation of the wrist when using a thermal probe to avoid heat buildup. It is important to inspect the radial styloid, the radioscapholunate ligament, the ulnar pre–styloid recess, and the dorsoulnar region beneath the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) subsheath.

FIGURE 20.4 Ablator removing synovitis with good outflow and inflow being maintained to avoid heating the tissues.

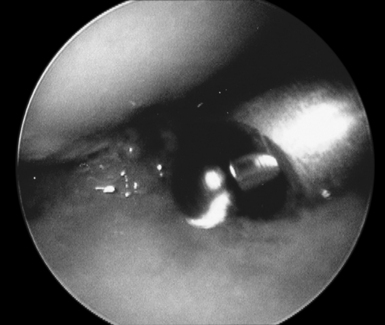

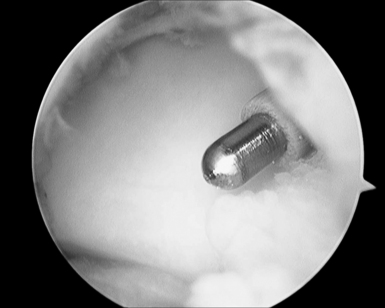

The previously described traction setup is similarly used for abrasion chondroplasty of the proximal pole of the hamate. Once the radial midcarpal portal is established, a 2.9–mm bur is inserted into the ulnar midcarpal portal. An average of 2.4 mm of the proximal pole should be excised to fully unload the hamatolunate articulation. This amount of bony resection does not affect the loading characteristics of the triquetrohamate articulation.9 The radial and ulnar midcarpal portals are used interchangeably in order to completely debride the proximal pole. The diameter of the 2.4–mm bur is used as a guide to the depth of resection. The postoperative dressing and protocol are similar to that following an arthroscopic wrist synovectomy.

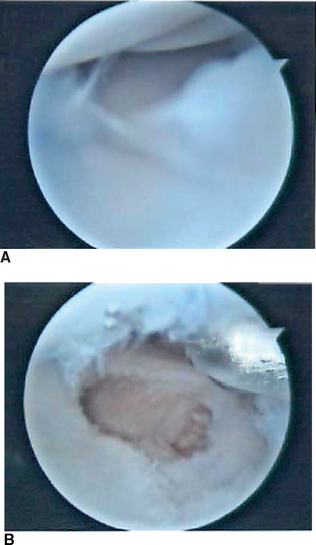

Radiocarpal arthritis is treated with abrasion arthroplasty in a manner similar to that described by Steadman et al. for the knee (Figures 20.6 through 20.8).10 The standard working portals are established as previously described. Any loose bodies are removed during the initial diagnostic survey. Once a focal area of chondral damage is identified, specially designed Linvatec awls (Linvatec, Key Largo, FL) (2.5 mm, 3.5 mm) are used to make multiple perforations (microfractures) in the subchondral bone plate. These perforations are made as close together as possible while maintaining an adequate bony bridge. They are typically 1 to 2 mm apart. The integrity of the subchondral bone plate should be maintained.

A shaver is not used on the articular cartilage. The released marrow elements (mesenchymal stem cells, growth factors, and other healing proteins) form a surgically induced super–clot that provides an enriched environment for new tissue formation.10 Marcaine and Kenalog are injected under direct visualization at the conclusion of the procedure. The rehabilitation program is crucial in optimizing the results of the surgery, and early range of motion is key. Dressings and closure are carried out as previously described.

Results

Wrist arthroscopy allows one to effectively perform a synovectomy, debride a torn TFCC, treat chondral defects and osteoarthritis, remove loose bodies, and resect the distal ulna and carpal bones. The surgeon should adhere to the anatomical principles that have been developed for open surgical procedures. “Ectomy” procedures of the wrist require a higher level of expertise from the surgeon, but when mastered provide considerable benefit to the patient.22 We have found that these procedures are an excellent adjunct in the multifaceted treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. They may also be of benefit in the treatment of other forms of arthritis. Superior results are obtained when it is combined with the treatment of the underlying cause.

In a review of 18 patients who underwent an abrasion arthroplasty for the proximal pole of the hamate, there were 10 excellent, 4 good, 3 fair, and 1 poor result—with a follow–up of 1 to 3 years. The poor result had associated radial carpal arthrosis and rheumatoid arthritis. The three fair results all had an associated lunotriquetral instability. The results following an arthroscopic chondroplasty have been variable. The durability of the fibrocartilage repair tissue that forms following microfracture is questionable, and the possibility of thermal damage to the subchondral bone and the adjacent normal articular cartilage following a laser/thermal chondroplasty exists.23

Summary

Although recent prospective, randomized, double–blind studies have demonstrated that the outcomes after arthroscopic lavage or debridement for knee osteoarthritis were no better than a placebo procedure, controversy still exists. The literature is scarce on the use of these procedures in the wrist.24 Reports of abrasion chondroplasty for the treatment of advanced wrist arthritis have been anecdotal in nature, but it has been quite successful in our hands.

1 Ekman EF, Poehling GG. Principles of arthroscopy and wrist arthroscopy equipment. Hand Clin. 1994;10(4):557-566.

2 Gupta R, Bozentka DJ, Osterman AL. Wrist arthroscopy: Principles and clinical applications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9(3):200-209.

3 Adolfsson L, Nylander G. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the rheumatoid wrist. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1993;18(1):92-96.

4 Adolfsson L, Frisen M. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the rheumatoid wrist: A 3.8 year follow-up. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1997;22(6):711-713.

5 Adolfsson L. Arthroscopic synovectomy in wrist arthritis. Hand Clin. 2005;21(4):527-530.

6 Roth JH, Poehling GG. Arthroscopic “-ectomy” surgery of the wrist. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(2):141-147.

7 Altman RD, Kates J, Chun LE, Dean DD, Eyre D. Preliminary observations of chondral abrasion in a canine model. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51(9):1056-1062.

8 Steadman JR, Briggs KK, Rodrigo JJ, Kocher MS, Gill TJ, Rodkey WG. Outcomes of microfracture for traumatic chondral defects of the knee: Average 11-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(5):477-484.

9 Harley BJ, Werner FW, Boles SD, Palmer AK. Arthroscopic resection of arthrosis of the proximal hamate: A clinical and biomechanical study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2004;29(4):661-667.

10 Steadman JR, Rodkey WG, Rodrigo JJ. Microfracture: Surgical technique and rehabilitation to treat chondral defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;391:S362-S369.

11 Larsen A, Dale K, Eek M. Radiographic evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis and related conditions by standard reference films. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1977;18(4):481-491.

12 Outerbridge RE. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43-B:752-757.

13 Yao J, Osterman AL. Arthroscopic techniques for wrist arthritis (radial styloidectomy and proximal pole hamate excisions). Hand Clin. 2005;21(4):519-526.

14 Nakamura K, Patterson RM, Moritomo H, Viegas SF. Type I versus type II lunates: Ligament anatomy and presence of arthrosis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2001;26(3):428-436.

15 Nakamura K, Beppu M, Patterson RM, Hanson CA, Hume PJ, Viegas SF. Motion analysis in two dimensions of radial-ulnar deviation of type I versus type II lunates. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2000;25(5):877-888.

16 Malik AM, Schweitzer ME, Culp RW, Osterman LA, Manton G. MR imaging of the type II lunate bone: Frequency, extent, and associated findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173(2):335-338.

17 Dautel G, Merle M. Chondral lesions of the midcarpal joint. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(1):97-102.

18 Viegas SF, Wagner K, Patterson R, Peterson P. Medial (hamate) facet of the lunate. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1990;15(4):564-571.

19 Viegas SF. The lunatohamate articulation of the midcarpal joint. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(1):5-10.

20 Haims AH, Moore AE, Schweitzer ME, et al. MRI in the diagnosis of cartilage injury in the wrist. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(5):1267-1270.

21 Amrami KK, Askari KS, Pagnano MW, Sundaram M. Radiologic case study: Abrasion chondroplasty mimicking avascular necrosis. Orthopedics. 2002;25(10):1018. 1107–08

22 Bain GI, Roth JH. The role of arthroscopy in arthritis. “Ectomy” procedures. Hand Clin. 1995;11(1):51-58.

23 Hunt SA, Jazrawi LM, Sherman OH. Arthroscopic management of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10(5):356-363.

24 Smith MD, Wetherall M, Darby T, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of arthroscopic lavage versus lavage plus intra-articular corticosteroids in the management of symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42(12):1477-1485.