Arthroscopic Lateral Retinaculum Release

Daniel A. Farwell and Andrew A. Brooks

Surgical Indications and Considerations

While surgical treatment (lateral patellar retinacular release) for maltracking of the patella has shown promising results,1 it is becoming less popular as an isolated procedure.2 The surgery appears less successful in patients that have severe chondromalacia, patella instability, or evidence of trochlear dysplasia.3–5 Latterman and associates6 state that “isolated lateral retinacular release has little or no role in the treatment of acute or recurrent patella instability. This procedure should be reserved for the few patients with a clearly identified lateral patella compression syndrome in presence of a tight lateral retinaculum and clearly discernable lateral retinacular pain.” Currently it appears that lateral patellar retinacular release is usually performed as an adjunct to other knee surgeries where patellofemoral misalignment is an issue.6 This chapter will deal with patellofemoral rehabilitation that should be considered an adjunct to any knee surgery where patella pain is an issue.

Adaptation resulting from chronic compression in the patellofemoral joint can lead to significant arthrosis in a wide variety of patients, both young and old. Pain, attributed to increased patellofemoral compression, occurs in different aspects of the joint, but the most common site is along the lateral aspect. This patellofemoral pain can originate from mechanical malalignment, the static or dynamic soft tissue stabilizers, or increased load placed across the joint as a result of various activities.7 Symptoms may include diffuse aches and pains that are exacerbated by stair climbing or prolonged sitting (i.e., flexion of the knees). Crepitus and mild effusion are often associated with patellofemoral arthralgia. Although complaints of “giving way” or collapse are more often linked with ligamentous instability, these symptoms also can be associated with patellofemoral pain. Patients may even complain of joint pain and “locking” when they are experiencing poor patella stabilization during flexion of the knee.

In examining the way lateral retinacular release procedures may affect the arthrokinematics of the patellofemoral joint, the focus should be on the relationship between patella tilt compression and associated tightness in the lateral retinaculum. The function of the patella is to increase the lever of the quadriceps muscle, thus increasing its mechanical advantage. For functional and efficient knee motion, the patella must be aligned so that it can travel in the trochlear groove of the femur. The ability of the patella to track properly depends on the bony configuration of the trochlear groove and the balance of forces of the connective tissue surrounding the joint.

Weakness and stiffness from the hip are factors that appear to influence poor patella alignment (gluteus medius weakness and iliotibial band [ITB] tension). Tensor fascia latae and gluteus maximus fibers combine to form a very thick, fibrous structure that attaches distally into the lateral tibial tubercle (Gerdy tubercle).8 The ITB slips into the lateral border of the patella, which interdigitates with the superficial and deep fibers of the lateral retinaculum. This design often leads to excessive compression over the lateral condyle and lateral border of the patella during dynamic activity.

Tilt compression is a clinical radiographic condition of the patellofemoral joint that can lead to retinacular strain (i.e., peripatellar effect) and excessive lateral pressure syndrome (i.e., articular effect).9 A case can definitely be made for a cause-and-effect relationship between tilt compression and retinacular strain. Chronic patella tilting and associated retinacular shortening cannot only produce significant lateral facet overload but also a resultant deficiency in medial contact pressure. This tilt compression syndrome may have simple soft tissue pain related to the shortening of the lateral retinacular tissue. If left untreated, then histologic studies of painful retinacular biopsies may reveal degenerative fibroneuromas within the lateral retinaculum of patients with chronic patellofemoral malalignment.10 Excessive lateral pressure syndrome results from chronic lateral patella tilt, adaptive lateral retinacular shortening, and resultant chronic imbalance of facet loads. It is prevalent in active, middle-aged adults. In younger patient populations, excessive lateral pressure during growth and development can alter the shape and formation of both the patella and trochlea.10

Nonoperative treatment of patella tilt should focus on mobilization of tight quadriceps muscles and the lateral retinaculum. Patellofemoral taping, bracing, and antiinflammatory medications also are quite helpful. Gait deviation and excessive foot pronation should be corrected to eliminate possible secondary influences on patellofemoral malalignment.7 The use of resistant weight training or isokinetic exercise (in conjunction with patella taping) can be beneficial in building quadriceps muscle strength.11

Patellofemoral Taping

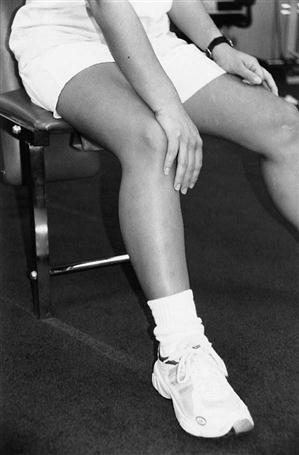

![]() McConnell patellofemoral taping has become a useful technique in the conservative (nonsurgical) rehabilitation of patellofemoral pain; it can also benefit patients after surgical lateral release as well. Controversy exists as to the mechanism behind the pain relief from taping. Whether via cutaneous stimulation, enhancement of patellofemoral ligaments, or improved vastus medialis oblique (VMO) timing, clinically we know that patellofemoral pain can be reduced or eliminated via its appropriate application.12,13

McConnell patellofemoral taping has become a useful technique in the conservative (nonsurgical) rehabilitation of patellofemoral pain; it can also benefit patients after surgical lateral release as well. Controversy exists as to the mechanism behind the pain relief from taping. Whether via cutaneous stimulation, enhancement of patellofemoral ligaments, or improved vastus medialis oblique (VMO) timing, clinically we know that patellofemoral pain can be reduced or eliminated via its appropriate application.12,13

Patellar taping has been shown to increase vasti muscle activity14,15 and may enhance knee joint proprioception after surgery.16 The McConnell patellofemoral program emphasizes closed-chain exercises to correct patella glide (Fig. 23-1), tilt (Fig. 23-2), and rotation, (Fig. 23-3) and allows for pain-free rehabilitation. The patient is evaluated dynamically during a functional activity such as walking, stepping down, or squatting. According to Maitland,17 “The aim of examining movements is to find one or more comparable signs in an appropriate joint or joints.” These comparable signs, or reassessment signs, are reevaluated after each patella correction to determine the effectiveness of the treatment. After an assessment of patella orientation, a specifically designed tape is used to correct for each patella orientation. The patellofemoral joint is principally a soft tissue joint, which suggests that it can be adjusted through appropriate mechanical means (i.e., physical therapy). Two primary components (glide and tilt) may be present either statically or dynamically. Patella orientation varies among patients and even from left to right extremities.

Glide Component

The amount of glide correction depends on the tightness of the structures and the relative amount of activity in the entire quadriceps musculature. The corrective procedure involves securing the edge of the tape over the lateral border of the patella and pulling or gliding the patella more medially. Although this technique is useful for most patellofemoral pain, it is not often used in the postoperative care of patients recovering from lateral retinacular release (see Fig. 23-1).

Tilt Component

Tilt correction is quite often used to stretch the deep retinacular fibers along the lateral borders of the knee. Increased tension in the lateral retinaculum along with a tight ITB (which inserts into the lateral retinaculum) can produce a lateral “dipping,” or tilt, of the lateral border of the patella (see Fig. 23-2).

When focusing on patients recovering from lateral retinacular release, the physical therapist (PT) should remember that the very tissues these taping techniques address have been surgically released. Although patella orientations have definitely been altered in patients after surgical release, muscle recruitment patterns and joint loading characteristics that may have contributed to the symptoms are still present.

McConnell taping procedures produce improved joint loading and allow the patient to return to a more active, pain-free lifestyle when used in conjunction with closed-chain functional exercises.18,19

Although conservative management remains the cornerstone of treatment for patients with anterior knee pain, some patients will not respond and continue to have pain and functional disability. If conservative (nonsurgical) treatment is unsuccessful in providing the patient with appropriate pain relief and function, then surgical intervention should be considered.20

In addition to subjective complaints and functional limitations, other indications for surgery include dislocation, subluxation, and failure of previous surgery with or without medial patella position.

Operative procedures that modify patella mechanics are most successful in treating patients with patella articular cartilage lesions. Lateral release procedures should ultimately produce a mechanical benefit to the patient, such as relieving documented tilt.21

Surgical Procedure

Review of the literature suggests strict indications for lateral release9:

1 Chronic anterior knee pain despite a trial of a nonoperative program for at least 3 months

Results may be disappointing for lateral release in the presence of the following conditions:

Patients with instability may require medial retinacular imbrication or a distal realignment in addition to an isolated lateral release.

The Southern California Orthopedic Institute (SCOI) technique of arthroscopic lateral release is performed in the supine position without the use of a leg holder; the tourniquet is inflated only when necessary. The procedure is performed with the arthroscope in the anteromedial portal. Routine arthroscopic fluid is used. An 18-gauge spinal needle is inserted at the superior pole of the patella and is used as a marker for the proximal extent of the release. The needle must be withdrawn as the electrosurgical electrode approaches it. With experience, the surgeon can omit the needle marker. The electrosurgical lateral release electrode is inserted through the inferior anterolateral portal using a plastic cannula to protect the skin. The procedure is performed with the generator setting at approximately 10 to 12 W of power. With the patient’s knee extended, the surgeon performs the release approximately 1 cm from the patella edge, progressing from distal to proximal using the cutting mode. The deep and superficial retinaculum, as well as the lateral patellotibial ligament, are released under direct visualization until subcutaneous fat is exposed. The extent of the proximal release is only to the deforming tight structures and should never extend beyond the superior pole of the patella.

An incomplete release is often secondary to inadequate release of the patellotibial ligament. Again, the tourniquet is not inflated during the procedure, and vessels are coagulated as they are encountered. An adequate release is confirmed by the ability to evert the patella 60°. After the release, the knee is passively moved through a range of motion (ROM) and correction of lateral overhang during knee flexion is confirmed. The arthroscope should be switched back to the accessory superolateral portal for this assessment. Usual postoperative dressings are applied after the arthroscopic procedure (sterile dressings and an absorbent pad held in place by an elastic toe-to-groin support stocking previously measured for the patient).

Postoperative rehabilitation includes muscle strengthening and ROM exercises the day of surgery, including quadriceps sets and straight leg raising. The patient continues to do these exercises at home the night of surgery and is given weight bearing as tolerated status with crutches immediately. Crutches are discontinued when adequate quadriceps muscle control has been obtained and patients can walk safely. The vast majority of patients use their crutches for less than 7 days, although some may need them for 2 to 3 weeks depending on quadriceps control.

The SCOI experience with arthroscopic lateral retinaculum release (ALRR) has been reported previously.22 The researchers monitored 39 patients with a history of recurrent patella subluxation or dislocation in 45 knees for an average of 28 months and noted good to excellent results in 76% of patients. Similar experiences with ALRR have been reported in the literature, with favorable results in 60% to 85% of cases.23 Arthroscopic treatment compares favorably with open realignment and has a lower complication rate. No postoperative hemarthrosis occurred in the SCOI series; hemarthrosis is the main complication reported in the literature, occurring in 2% to 42% of cases. Small’s review24 of 194 cases of ALRR, performed by 21 arthroscopic surgeons, found hemarthrosis associated with 89% of the 4.6% total complications. Careful coagulation of vessels without an inflated tourniquet can reduce hemarthrosis. If strict criteria are met and proper surgical techniques are used, then a consistent result can be obtained with these patients.

The complexity of the patellofemoral articulation and its associated disorders are evident by the significant body of literature on the subject and the abundant surgical procedures involving the joint. A thorough clinical evaluation, including history and physical and radiographic examination, helps to clarify the diagnosis of patellofemoral disorder. Use of the arthroscope for the electrosurgical lateral release is an effective component in the armament of knee surgeons for patients with persistently symptomatic patellofemoral disorders who meet the surgical indications described.

Therapy Guidelines for Rehabilitation

Phase I (Acute Phase)

TIME: 1 to 2 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Decrease pain, manage edema, increase weight-bearing activities, facilitate quality quadriceps contraction (Table 23-1)

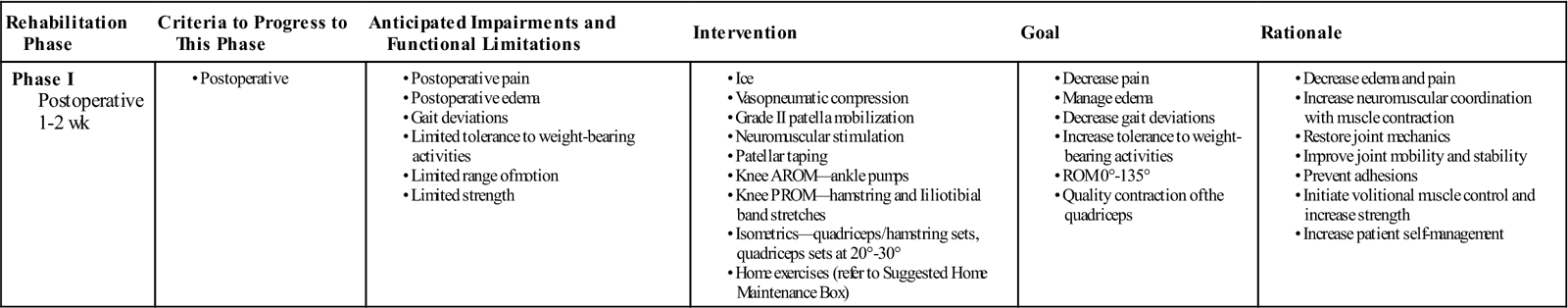

TABLE 23-1

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase I Postoperative 1-2 wk |

• Ice

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

AROM, Active range of motion; PROM, passive range of motion.

After knee surgery the goal of rehabilitation is to prevent loss of muscle strength, endurance, flexibility, and proprioception. These issues often are difficult to address immediately after lateral release. The procedure is often associated with significant hemarthrosis resulting from sacrifice of the lateral geniculate artery.25 Therefore the acute phase of treatment should focus on managing edema and decreasing pain. The use of vasopneumatic compression, electrical stimulation, ice, and intermittent elevation of the limb can assist in decreasing the patient’s swelling.

Other strategies to both decrease joint effusion and begin restoring joint mobility include grade II (mobilizations performed shy of resistance in an effort to decrease pain)26 patella mobilizations, active calf pumping exercises, and the application of McConnell taping27 specific to acute lateral release rehabilitation (Fig. 23-4). This procedure places a very mild tilt on the patella, providing a small amount of length to the repair site or lateral retinacular tissue. The tape maintains the new alignment, preventing adhesions that may bind down the released retinaculum during tissue healing. Other taping procedures such as unloading the lateral soft tissue may assist in decreasing pain and discomfort during exercise (Fig. 23-5). This procedure is beneficial in decreasing joint effusion and adds joint stability. It is often used in combination with a patella tilt correction.

Phase II (Subacute Phase)

TIME: 3 to 4 weeks after surgery

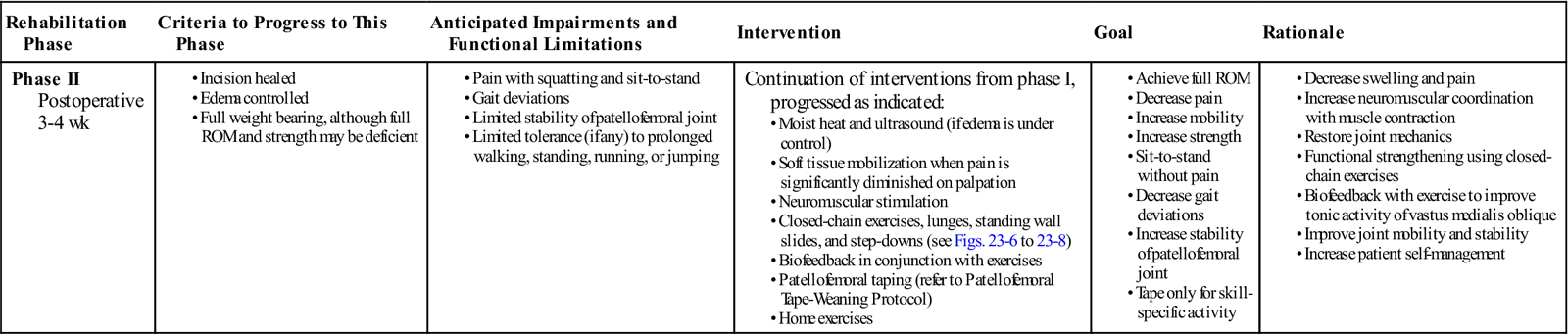

GOALS: Continue to manage edema and pain, improve sit-to-stand transfer activities, improve strength and stability of the patellofemoral joint, progress functional training to return activity to previous levels (Table 23-2)

TABLE 23-2

< ?comst?>

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

As the patient’s swelling and pain subside (1 to 2 weeks), the patient moves into a subacute phase. During this phase a more direct and aggressive type of treatment is implemented for the knee. Heat modalities (i.e., moist heat, ultrasound) are used to assist in the absorption and removal of waste products within the joint. Their influence on the cardiovascular system produces increased capillary permeability and vasodilation. The vasodilation brings increased oxygen and nutrients to the knee, which assist in the healing and repairing of the surgically altered tissue.28 Increased blood flow produces increased capillary hydrostatic pressure. Therefore heat modalities can be very beneficial at this stage of rehabilitation, but only if the patient’s effusion is under control. If the patient’s effusion is displacing the patella from the trochlear groove or the patient cannot perform active isometric quadriceps contractions, then the joint effusion is significant.

![]() Heat applications may be contraindicated until edema is no longer a concern. Soft tissue mobilization can be beneficial at this stage to increase circulation, decrease swelling, mobilize healing tissue, and decrease hypersensitivity in the knee joint.10 Deep massage can assist in the reabsorption of fluid within the knee, yet manipulation of soft tissue structures over the lateral aspect of the knee should be avoided to prevent aggravation of the trauma from surgery.

Heat applications may be contraindicated until edema is no longer a concern. Soft tissue mobilization can be beneficial at this stage to increase circulation, decrease swelling, mobilize healing tissue, and decrease hypersensitivity in the knee joint.10 Deep massage can assist in the reabsorption of fluid within the knee, yet manipulation of soft tissue structures over the lateral aspect of the knee should be avoided to prevent aggravation of the trauma from surgery. ![]() Soft tissue mobilization should not be initiated in the area of lateral structures before the tissues have begun to heal (1 to 2 weeks) and pain is significantly diminished on palpation of the entire patellofemoral joint.

Soft tissue mobilization should not be initiated in the area of lateral structures before the tissues have begun to heal (1 to 2 weeks) and pain is significantly diminished on palpation of the entire patellofemoral joint.

Electrical stimulation (ES) is used to assist in activation of the quadriceps muscle. Specific benefits include decreasing joint edema, increasing local blood flow to the muscle, promoting increased muscle tone, and controlling postoperative pain.29,30 Electricity also can be used to retard quadriceps atrophy, which results from immobilization or inhibition of the muscle.31 When used in combination with active isometric and isotonic exercises, ES retrains transposed muscles and promotes muscle awareness in regaining volitional muscle control postoperatively.28

Experiments conducted by scientists in the USSR in the 1970s examined the possibility of producing greater intensity of muscle contraction with electrical current. Some studies have found the use of ES during immobilization produces a significant increase in muscle strength.24,27 By using ES early in the rehabilitative process, PTs can prevent the loss of oxidative capacity, thus shortening postoperative rehabilitation and conditioning time and allowing a more rapid return to functional activities.32 Although ES can be of great benefit, it should not be used as a replacement for postoperative rehabilitation and strengthening exercise programs.33

In summary, the use of modalities is beneficial in aiding healing by decreasing acute reactions and altering blood flow, which may provide low-level analgesic effects.29,34 Understanding the action of these modalities and the way they influence healing is important in predicting their usefulness and appropriateness in the rehabilitation of patients after lateral retinacular release.

Strengthening

Strengthening of the entire lower kinetic chain is the goal in most patients suffering from anterior knee pain. This goal is no different for patients after lateral retinacular release. Although special attention is paid to the quadriceps muscle, particularly the VMO, it is the balanced contraction in the vasti group as a whole that is the ultimate goal. Richardson20 examined the activity level of the quadriceps, specifically the VMO, to better understand the activation patterns of the quadriceps during dynamic motion. The quadriceps were monitored with surface electromyography through a full arc of motion in both patients suffering from patellofemoral pain and normal patients. The VMO produced a tonic (constant) pattern of activation throughout a full (0° to 135°) arc of motion in pain-free patients; a phasic (intermittent) activity pattern was observed in patients with patellofemoral pain. A consistent activation of the entire quadriceps is the goal in quadriceps strengthening. Quality of motion should be emphasized over relative quantity. Exercise beyond 20° flexion (20° to 135°) increases the surface area of contact and gives better stability within the trochlear groove. Although the development of muscle strength is important, it is not the only goal of rehabilitation. Muscle endurance, flexibility, and the development of correct proprioceptive loading through the entire lower extremity (LE) must be addressed as well. These goals can be accomplished in patients recovering from surgical lateral release by protecting the surgical repair through modalities that speed the tissue repair process and protective taping that adds stability and promotes early functional rehabilitation. Wittingham, Palmer, and Macmillan35 recently concluded that a combination of patellar taping and exercise was superior to the use of exercise alone. Early quadriceps activation includes isometric quadriceps sets in varying degrees of flexion produced by a proximal load-bearing shift with increased knee flexion.36 This allows for early muscle strengthening even while joint effusion may still be causing pain in a closed-chain (joint loaded) position.

![]() When effusion and pain have been eliminated for 7 to 14 days, a gradual increase in activity may begin, with cryotherapy being used after activity. During LE rehabilitation, after the patient can stand or load the joint, the emphasis should be on closed-chain activity because of its relevance to function. The goal is to advance the patient toward functional activities and then slowly introduce a patient-specific exercise program. Specific closed-chain exercises allow for the selection and stimulation of the appropriate muscles at the proper time.37 These factors, combined with gradual muscle inhibition of the antagonist, produce smooth, coordinated loading of the entire LE.

When effusion and pain have been eliminated for 7 to 14 days, a gradual increase in activity may begin, with cryotherapy being used after activity. During LE rehabilitation, after the patient can stand or load the joint, the emphasis should be on closed-chain activity because of its relevance to function. The goal is to advance the patient toward functional activities and then slowly introduce a patient-specific exercise program. Specific closed-chain exercises allow for the selection and stimulation of the appropriate muscles at the proper time.37 These factors, combined with gradual muscle inhibition of the antagonist, produce smooth, coordinated loading of the entire LE.

Although McConnell patellofemoral taping is the modality of choice used by the authors of this chapter to bolster stability at the onset of exercise, a variety of braces may be beneficial in supporting the patellofemoral joint after surgery. Almost any elastic, compressive support around the patellofemoral joint produces an improved ability to exercise. The concept of proprioceptive feedback, together with comfort and affordability, makes postoperative McConnell patellofemoral taping or nonspecific bracing of the knee desirable in patients who do not respond to exercise alone.

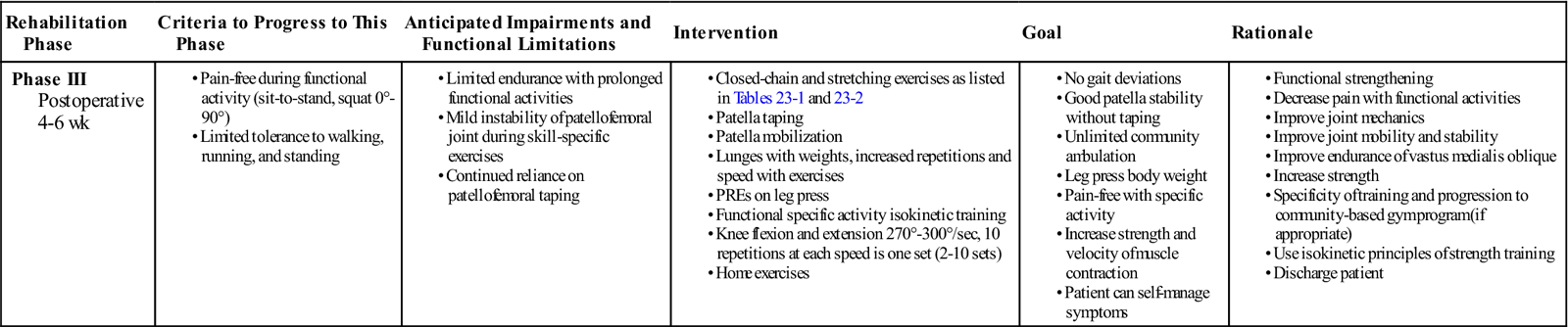

Phase III (Advanced Phase)

TIME: 5 to 6 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Patient self-manages edema and pain, performs gait without deviations, and has unlimited ambulation (Table 23-3)

TABLE 23-3

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase III Postoperative 4-6 wk |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

By phase III patients should have their pain under control using little if any external support (brace or tape). They may continue to benefit from stretching, patella mobilization, and taping in addition to ice after exercise. However, this phase is designed to take the patient back to the preinjury level of function. Exercises are progressed through specificity of training principles. By breaking down the activity into its core components, the PT can assess patellofemoral and LE function for any deviations or barriers to performance.

Again, any exercise that increases knee pain and/or swelling needs to be modified or discontinued. After further progress has been gained, the therapist can reassess the patient and attempt the exercise again.

Closed kinetic chain progression consists of the following:

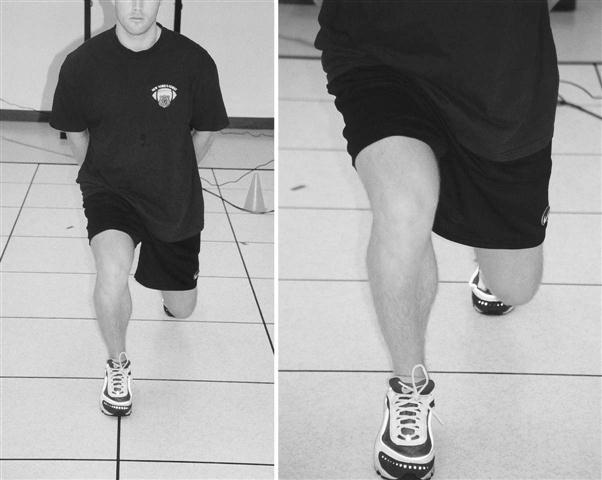

1 Lunges with 5 lb weights in a long-stride position (Fig. 23-6)—Patients must activate the quadriceps and hold the contraction from 0° to 30° eccentrically and back to 0° concentrically without stopping, while moving slowly and maintaining proper alignment.

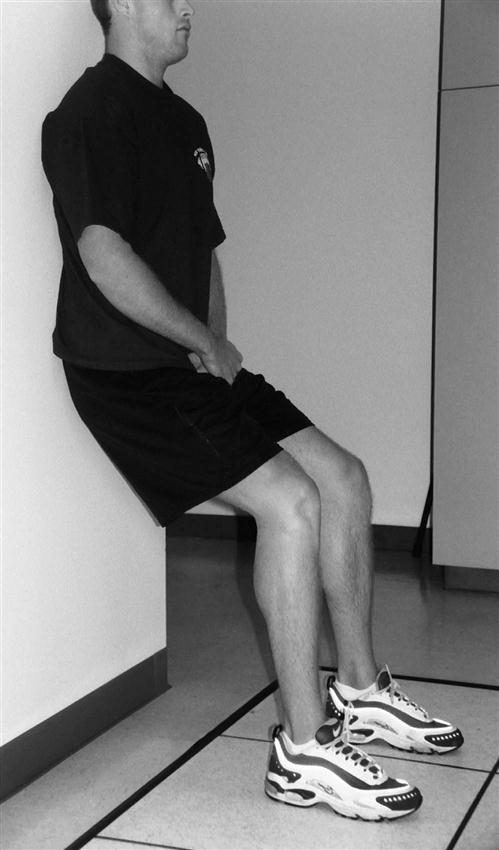

2 Wall slides at various degrees of flexion with 1-minute holds to promote fatigue (Fig. 23-7)—The patient should progress from 0° to 45°; if a certain angle in the arc of motion appears weaker, then the patient can perform isometric holds at the angle of weakness.

4 Functional double-limb squats with elastic tubing

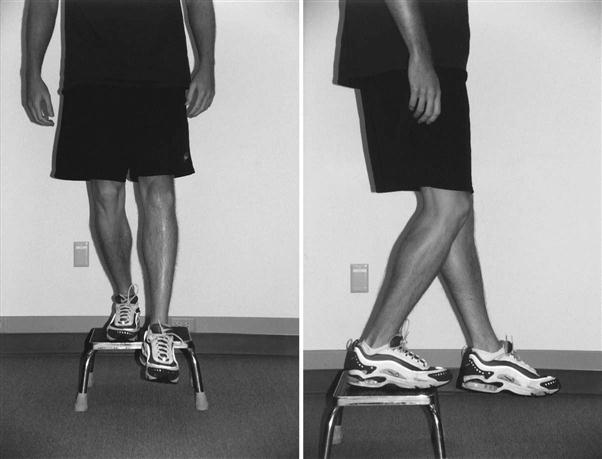

6 Step-down exercises with an increase in height of step and speed of movement—Proper alignment is crucial, along with slow, controlled movement. The patient must activate the quadriceps before motion is initiated and hold the contraction until heel contact with the opposite leg (Fig. 23-8).

7 Resistive leg press using progressive resistance exercise protocols for weight38,39

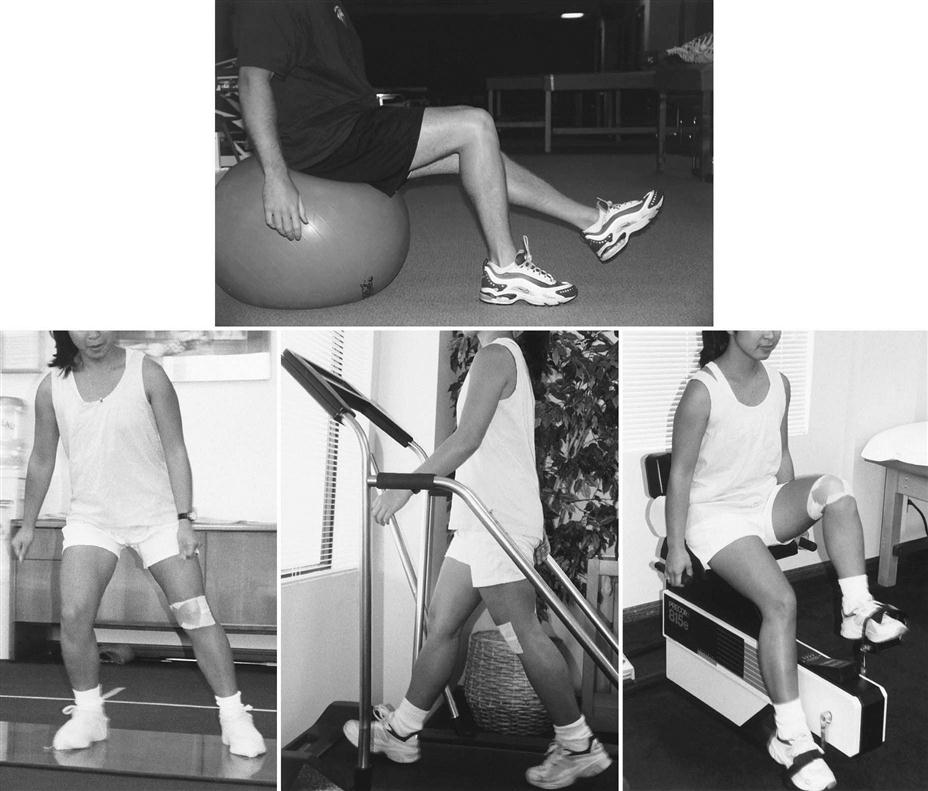

Activity-specific exercises (Fig. 23-9) may include the following: stationary cycle, stair-climbing machine, slide board, and treadmill. The authors of this chapter recommend a 6-week progression to presurgery activity level. Isokinetic exercise is introduced in this phase at a training velocity spectrum protocol between 270° and 300°/sec.40 The patient performs 10 repetitions at each speed in a ladder progression (50 repetitions equal one set). Patient tolerance for exercise determines the number of sets performed (2 to 10 sets). After patients can perform the exercises with good control of the patellofemoral joint, they are weaned from formal physical therapy and encouraged to continue their home exercise program as appropriate.

Once you have arrived at the decision to move the patient into a home program, it is important to understand how variable the long-term results can be following this procedure. Recent studies describe favorable results (73% to 86%) after 1 year.41 This same study indicates that the results are far less favorable (29% to 30%) if the follow-up period is extended to 4 or 5 years. Questions exist concerning the appropriateness of an isolated lateral release procedure alleviating the biomechanical symptoms it is designed to address.42 This evidence underscores the importance in identifying muscle strength and muscle length imbalances in the entire lower limb. Any abnormal LE alignment needs to be addressed in advance of discharge to a self-guided program.

Troubleshooting

Postural Alignment

A lateral retinacular release procedure produces immediate effects on the patella orientation of the knee, yet the entire lower kinetic chain may still have alignment issues that need to be addressed. When assessing a patient’s functional status, the PT should consider equalizing leg lengths, balancing foot posture, restoring normal gait, and regaining appropriate muscle flexibility and strength, which will lead to a restoration of normal posture and balance.10 By observing static alignment issues, PTs can gather valuable information regarding the way the patient will function dynamically. The interaction of poor alignment measures and quadriceps contraction has been examined.43 This study compared static and dynamic patellofemoral malalignment measures in subjects with anterior knee pain. Quadriceps contraction altered the malalignment in both type and severity in more than 50% of cases.

The literature suggests that excessive pronation at the foot is a primary problem because of its association with patellofemoral pain, which inhibits the balance of the entire lower kinetic chain.7 Increased pronation may lead to increased valgus, compensatory external rotation of the foot and tibia, and a resultant predisposition to lateral patella tracking with dynamic activity.44 In such cases, orthotic correction may be indicated even after a lateral retinacular release procedure to restore proper loading mechanics through the knee.

Quadriceps Inhibition

Many clinicians tend to use the term quadriceps inhibition as though it were synonymous with quadriceps weakness, which is not an accurate description. Reflex quadriceps inhibition is defined as the inability to perform a quadriceps contraction voluntarily because of direct neurologic suppression.30,45

Does true quadriceps inhibition exist? Numerous research articles on the subject describe several mechanisms that could produce a neurogenic influence on voluntary control of the quadriceps.46,47 The effect of pain on the overall activation of the quadriceps has been examined as a possible cause.48,49 Effusion also can impair activation of the quadriceps muscle.50,51 Mechanical receptors within the patellofemoral joint may influence quadriceps function through proprioceptive input.52,53 Other factors may include training methods, joint position, aging, and even the possible effects of medication.

![]() Any problem resulting in decreased activation of the quadriceps is detrimental to the rehabilitation process. With full activation of the quadriceps femoris muscle, proper strengthening exercises should produce excellent results. However, if voluntary control is absent or compromised, then atrophy and weakness may result. If this situation persists, then volitional exercise protocols may be ineffective and thus temporarily inappropriate for these patients.

Any problem resulting in decreased activation of the quadriceps is detrimental to the rehabilitation process. With full activation of the quadriceps femoris muscle, proper strengthening exercises should produce excellent results. However, if voluntary control is absent or compromised, then atrophy and weakness may result. If this situation persists, then volitional exercise protocols may be ineffective and thus temporarily inappropriate for these patients.

Because of the nature of a lateral retinacular release procedure, pain and especially effusion are quite common after surgery. Therefore any treatment techniques that address pain and swelling will ultimately assist in improved recruitment of the quadriceps femoris muscle.

Patellofemoral Tape-Weaning Protocol

Patients using McConnell taping need to learn how to tape themselves. The tape loosens according to the aggressiveness of the patient’s activity. The patient should therefore be taught to tighten the tape when necessary.

The patient only needs to wear tape while training the quadriceps to maintain the newly acquired length in the lateral structures. The tape should be removed at night and the skin should be cleaned. This gives the skin a resting period from the pull and friction produced by the tape.

The patient begins closed-chain exercises when pain and effusion are under control. Early home exercises stress “little bits often,” meaning multiple VMO sets or quadriceps contractions are performed throughout the day and are linked with a patient’s lifestyle. For example, the PT may instruct a patient to perform a quadriceps contraction every time he or she sits down in a chair, palpating the VMO for feedback. When driving a car, the patient may perform a quadriceps set at every stoplight, taking care to leave the foot firmly on the brake. As the patient begins to recruit a quality quadriceps contraction successfully, goal setting enters into the program and the patient is asked to attempt repetitions of closed-chain exercises (i.e., lunges, wall slides, squats, step-downs). The more the patient practices, the faster the skill to activate a quality quadriceps muscle contraction is learned.

The patient is ready to be weaned off the taping protocol and continue the program with specific sports-related activity and training when he or she can do the following:

1 Sustain a quarter squat for 1 minute against the wall without pain.

2 Sustain a half squat for 1 minute against the wall without pain.

If functional activity produces pain and the patient is using patella taping, the PT should first assess the taping procedure to ensure it is correct. The clinician may need to make small adjustments in tension and direction. At the time of discharge from the clinical facility, the patient needs to remember how to self-mobilize the patella (Fig. 23-10), as well as proper alignment and the postural issues associated with closed-chain exercises; the patient should be reminded that exercise should be painless.

Clinical Case Review

1George has been having chronic anterior (patellofemoral) knee pain with recurrent subluxation. He is seeing you for his shoulder rehabilitation and wants to know if surgery (ALRR) is an option for him. What should you consider in your response?

Isolated lateral retinacular release has little or no role in the treatment of acute or recurrent patella instability. This procedure should be reserved for the few patients with a clearly identified lateral patella compression syndrome in the presence of a tight lateral retinaculum and clearly discernable lateral retinacular pain.

2Kathy is a 17-year-old soccer player that underwent ALRR because of chronic anterior knee pain. She comes for her 2-week postoperative evaluation. What should be the main focus of her postoperative rehabilitation?

Given the chronicity of her symptoms, the therapist should evaluate LE mechanics during gait and with dynamic activities when appropriate. The clinician should focus initially on hip strength and ankle mechanics (pronation dysfunction). Hip weakness can cause a valgus position of the knee, creating increased patellofemoral stress. The hip external rotators and abductors (especially the gluteus medius) are a major component in positioning the knee in proper alignment. Ankle mechanics should also be fully explored and orthotics initiated if appropriate.

3Rebecca is 24 years old. She had ALRR performed on her right knee 18 days ago. Treatment has focused on decreasing joint effusion, pain, and discomfort. Over the past 2 days her pain has increased, with redness around the knee. What should be done?

Because of the increase in temperature and redness (signs of potential infection), the clinician should notify the physician immediately.

4Sarah is a 17-year-old basketball player who had ALRR 3 weeks ago. She is complaining about her knee “giving out” during walking. She notes minimal pain, but continues to note pronounced swelling around the knee, especially laterally.

In exploring her situation further, it was noted that she was not able to perform an adequate quadriceps contraction. Quadriceps inhibition is a result of the continued edema. A more aggressive edema management program (i.e., elevation, compression, ES three times a day) was initiated along with therapy treatment consisting of ES in conjunction with quadriceps isometrics. A single-point cane was used in the interim until she could demonstrate adequate quadriceps control with walking.

5Diane is 33 years old. She has a history of anterior knee pain for 2 years. Before having ALRR, she used orthotics because she overpronated during gait. She had surgery 6 weeks ago. Complaints of pain are minimal to nonexistent if she avoids all aggravating factors. However, she generally has some soreness from activities of daily living around the home and from taking care of two young children. Diane is performing all the exercises mentioned in phase I and most exercises in phase II without pain. However, she has pain during functional double-leg squats with knee flexion exceeding 60° and knee pain with step-downs from a 4-inch step. What may help Diane progress with her exercise program?

Diane was evaluated for patellofemoral symptoms and treated with the McConnell method of taping. She was able to progress with the closed-chain exercises when the appropriate McConnell taping procedure was used. She was able to perform double-limb squats to 80° of knee flexion without pain. She also could perform two sets of 10 repetitions of step-downs on the 4-inch step without pain. Pain with the single-limb squat persisted but lessened. Therefore, single-limb squats were not performed until they could be done without pain.

6Travis is 3 weeks postoperation and is having trouble with maintaining a good quadriceps contraction. What exercises can be performed to address this issue?

Early quadriceps activation should include isometric quadriceps sets in varying degrees of flexion produced by a proximal load-bearing shift with increased knee flexion. This allows for early muscle strengthening even while joint effusion may still be causing pain in a closed-chain (joint loaded) position.

7What closed-chain exercises are appropriate to perform once ROM is obtained and pain is under control?

• Lunges in a long-stride position (see Fig. 23-6)

• Wall slides at various degrees of flexion with 1-minute holds to promote fatigue (see Fig. 23-7)

• Functional single-limb squats from 0° to 30° directly over the midfoot

• Functional double-limb squats with elastic tubing

• Sit-to-stand at increased speed and repetition

• Step-down exercises with an increase in height of step and speed of movement (see Fig. 23-8)

• Resistive leg press using progressive resistance exercise

• Standing (four-wall) elastic tubing exercises for hip flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction

8Brian is making good progress in his rehabilitation program with the adjunct of patella taping (medial glide). He asks how long can he leave the tape on and will he have to tape his knee forever?

The patient only needs to wear tape while training the quadriceps to maintain the newly acquired length in the lateral structures. The tape should be removed at night and the skin should be cleaned. This gives the skin a resting period from the pull and friction produced by the tape. Patients using McConnell taping will need to learn how to tape themselves. The tape will loosen according to the aggressiveness of the patient’s activity. The patient should therefore be taught to tighten the tape when necessary.

The patient is ready to be weaned off the taping protocol and continue the program with specific sports-related activity and training when he or she can do the following: