CHAPTER 23 Arthroscopic Excision of Dorsal Ganglions

Arthroscopic dorsal wrist ganglion resection offers several theoretical advantages over open techniques, including improved recovery, better joint visualization, lower complication and recurrence rates, and more satisfying cosmetic results. Initial outcomes after arthroscopic resection of dorsal wrist ganglia have been favorable.1–3 Although arthroscopic resection of dorsal wrist ganglion cysts is a procedure that is becoming more accepted, several questions remain unanswered. Based on a critical view of the sparse literature on the subject and on clinical observations, this chapter attempts to clarify the ambiguity surrounding arthroscopic dorsal wrist ganglion resection and to determine whether this is a useful technique to add to the arsenal or a triumph of technology over reason.

ANATOMY

Intra-articular Cystic Stalks

In the current literature, the exact roles of intra-articular cystic stalks are somewhat vague. Earlier reports implied, but did not specifically state, that identification and surgical excision of the stalk are paramount when standard arthroscopic techniques are used for ganglion excision. However, the presence of this important structure has been variably reported in the literature. Osterman and Raphael1 identified a stalk in two thirds of their patients undergoing arthroscopic ganglion excision. Although one third of their patients had no identifiable stalk, ganglions were successfully excised with no recurrences. Other studies have reported a stalk incidence as low as 10%.2–4 Despite vastly different reports on stalk identification, the importance of such pathology must be questioned. Rather than a cystic stalk, Edwards and Johansen4 described intra-articular cystic material and redundant capsular tissue in most of their patients with ganglion cysts. This finding, which was more consistently evident than the stalk, was the focus of their resection.

Intra-articular Associations

The dorsal ganglion may be an overt sign of intra-articular pathology. Povlsen and Peckett5 found intra-articular abnormalities in 75% of patients with painful ganglia. They concluded that, like the popliteal cyst in the knee, the dorsal ganglion was a marker of joint abnormality. Osterman and Raphael1 found abnormalities in 42% of their cases, predominately findings at the scapholunate ligament (24%), the triangular fibrocartilage (8%), and the lunatotriquetral ligament (3%) and significant chondromalacia. Despite the fact that only the ganglion was treated, wrist pain resolved in all cases. Edwards and Johansen4 elaborated on this notion by showing that most ganglia are associated with type II and III scapholunate and type III lunatotriquetral laxity (Table 23-1). Although it is reasonable to propose that increased intercarpal laxity may contribute to ganglion formation, the actual significance is unclear, given that the natural incidence of these ligamentous laxities in the general population is not known.

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Attenuation and/or hemorrhage of interosseous ligament as observed from the radiocarpal joint. No incongruence of carpal alignment in midcarpal space. |

| II | Attenuation and/or hemorrhage of interosseous ligament as observed from the radiocarpal joint. Incongruence and/or step-off as observed from midcarpal space. A slight gap (<2 mm) between carpals may be present. |

| III | Incongruence and/or step-off of carpal alignment are observed in the radiocarpal and midcarpal spaces. The width of a 2-mm probe may be passed through the gap between carpals. |

| IV | Incongruence and/or step-off of carpal alignment are observed in the radiocarpal and midcarpal spaces. Gross instability occurs with manipulation. A 2.7-mm arthroscope may be passed through the gap between carpals. |

Adapted from Geissler WB, Freeland AE, Savoie FH, et al. Intracarpal soft-tissue lesions associated with an intra-articular fracture of the distal end of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:357-365.

TREATMENT

Indications and Contraindications

Indications and contraindications for arthroscopic dorsal wrist ganglion resection are still evolving. Ho and colleagues2 reported two recurrences after resection of ganglia originating from the midcarpal joint. They concluded that arthroscopic resection was not indicated for cysts originating from the midcarpal joint. Many would agree that most dorsal wrist ganglia originate from the scapholunate interval. Given the capsular limitation in the wrist, this interval is only partially visualized from the radiocarpal joint. One study4 observed that cysts communicated with the midcarpal joint in 75% of cases. In the same report, 25% of cysts were accessed exclusively through the midcarpal joint, which suggests that evaluation of the midcarpal joint is mandatory for successful resection. Whereas most cysts may be resected successfully through an isolated radiocarpal portal, some require supplemental débridement from the midcarpal joint.

Regarding recurrent cysts, one group of investigators suggested that recurrent cysts after previous open surgical excision should be considered a contraindication for arthroscopic resection.6 Appropriate concerns are the risk of injury to the extensor tendons because of their potential displacement by the scar from the previous surgery. For this reason, most studies have identified recurrence as an exclusion criterion. One significant exception was a series in which 15% of the patients had recurrent ganglia, and outcomes were comparable to those of primary cyst resections. Based on this experience, the authors stated that arthroscopic resection of recurrent cysts is not contraindicated. In fact, it may be helpful in identifying a potential cause of the recurrence. Studies have identified intra-articular abnormalities such as ligament tears, excessive intercarpal laxities, chondromalacia, and triangular fibrocartilage tears as being associated with ganglion cysts.1,4 It is unclear whether such findings contribute to cystic development, but, to the degree that they have a role, arthroscopy is more effective than open excision at identifying and addressing these abnormalities. Given a recurrent cyst, an arthroscopic evaluation may identify a partial scapholunate ligament tear that could be débrided, thereby lowering the probability of further recurrence. An open technique may not identify the cause as easily and therefore may doom the recurrent excision to another recurrence.

Cosmetic reasons sometime drive decisions to pursue any endoscopic technique. Although an open incision across the dorsum of the wrist may not seem excessive to a surgeon, the patient may have another perspective. One study reported a very high postoperative satisfaction rate, despite the fact that 17% of the patients were asymptomatic preoperatively and opted surgery for cosmetic reasons.4 There has been no similar report for open resections. The implication is that it would be reasonable to offer arthroscopic ganglion resections for patients who are primarily interested in the cosmetic appearance of their hands.

Arthroscopic Technique

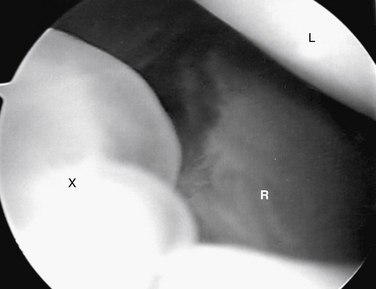

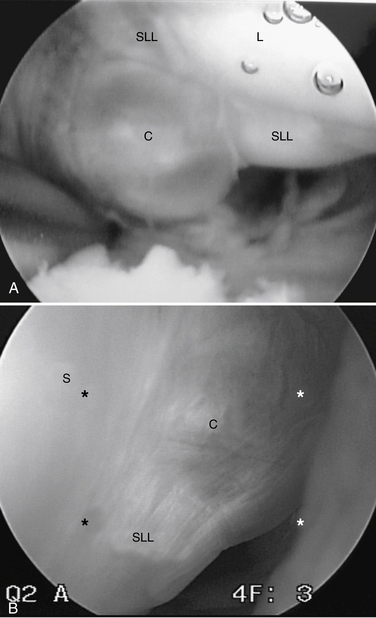

Before excision of a dorsal wrist ganglion, a tourniquet is placed as a precaution, and it is inflated in the event that intra-articular bleeding obscures visualization. While the patient’s arm is suspended in a traction tower with 5 to 10 pounds of traction applied, a 6-R or 6-U portal is created as a visualization portal. The more radial 3-4 or 4-5 portal is avoided at this time, to prevent inadvertent decompression of the cyst. After the 2.7-mm arthroscopic camera is directed toward the dorsal compartment of the wrist, the capsule adjacent to the scapholunate ligament can be visualized. Occasionally, a sessile or pedunculated protrusion into the joint can be seen in the area where the extrinsic capsule joins the distal portion of the dorsal scapholunate ligament. This capsular reflection serves as part of the barrier between the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints, and the protrusion located here has been termed the cystic stalk (Fig. 23-1). More often, the surgeon may be impressed with the amount of synovitis and redundant capsule in this area instead of an actual stalk.

FIGURE 23-1 Cystic stalks. A, Pedunculated. B, Sessile. C, cyst; L, lunate; SLL, scapholunate ligament.

The focus of the resection begins at the site of the ganglion stalk or redundant capsular material, if identified. This billowing, redundant material appears different from typical reactive synovitis. Although its exact significance is unclear, it seems to be continuous with the capsule that lies adjacent to the cyst. With this landmark, surgeons may confidently begin the capsulotomy. If neither structure is identified, the débridement begins adjacent to the dorsal scapholunate ligament and distal capsular reflection. Commonly, the cyst travels within the capsular reflection as it communicates with the scapholunate joint. Care should be taken to keep the blade of the shaver away from the scapholunate ligament at all times. On initial débridement of the capsular reflection, occasionally a flash of viscous cystic fluid may be visualized escaping into the joint. Débridement continues until approximately 1 cm of capsule has been removed.

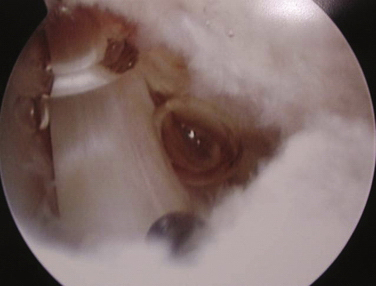

A common mistake is to make the capsulotomy too small, which is easy to do under magnification. The 2.9-mm shaver is helpful as a reference in gauging the size of the capsulotomy. Another common mistake is to create an incomplete capsulotomy that fails to communicate with the extra-articular space. We advise direct visualization of the extensor tendons to verify that a complete capsulotomy has been performed (Fig. 23-2). Removal of the cystic sac is not necessary, because it often resorbs over time after it is detached from its origin at the joint. If the cyst is particularly large, resorption may take some time, and patients may complain about residual prominence on the dorsum of the hand. Removal of the truncated sac may be performed by pulling it out of the 3-4 portal with a hemostat. Because this is a blind maneuver and the risk of neuroma formation is relatively high, we think that, if removal of the cystic sac is elected, it should be done arthroscopically from inside the joint, provided that the surgeon is comfortable with the technique. Careful extensor tenosynovectomy may be performed at the same time with the shaver, if desired.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Immediately postoperatively, digital motion is encouraged; sutures are removed in 7 to 10 days. Very seldom is any supervised therapy required. If there is residual fullness over the ganglion or its portal, the use of an elastomer as a pressure scar modulator may be helpful. Activity is resumed as tolerated, and the patient is advised against forceful loading of the wrist for 4 weeks. The theoretical advantages of a minimally invasive procedure to reliably remove wrist ganglion cysts seem intuitive but have not been validated until recently. Reduced recovery times, less postoperative pain, and quicker returns to work and athletics have been reported.4,6

Patients can expect decreased pain and increased function within 6 weeks after surgery. Outcome surveys, often regarded as the most important assessment of patients, have documented considerable improvements in the short and the long term.4 However, positive short-term outcomes cannot be referenced to open excisions, because there have not been comparable reports dealing with these procedures.

Although an increasing number of studies have demonstrated that arthroscopic ganglion resection is a safe and effective technique with a predictable and easy recovery, there has been only one prospective, randomized study comparing arthroscopic resection with more traditional open techniques.7 This study evaluated patients at 4 to 8 weeks and again at 1 year postoperatively and could find no difference in outcomes. Most would agree, however, that the true benefits of a minimally invasive arthroscopy would be most profound within the first 4 weeks. No study has compared the two techniques and specifically assessed patient outcome during this defining time. Until this is done, it is difficult to make any meaningful comparisons between arthroscopic and open resections.

RECURRENCES AND COMPLICATIONS

Recurrence rates have been low (0% to 10%) in virtually every report,1–3 implying that the recurrence rate for arthroscopic resection may be less than that for open excision, which typically has slightly higher recurrence rates. However, most studies had small cohort sizes, selection bias, and poorly defined follow-up, all of which could potentially distort the actual recurrence rates. In four separate studies3,4,7,8 with a combined cohort of 233 patients undergoing arthroscopic ganglion resection and an average follow-up of 2 years, only seven recurrences were reported. One prospective series8 comparing arthroscopic and open resection found no statistical difference in recurrence rates (10.7% versus 8.7%, respectively). Based on a critical review of the relevant literature, recurrence rates for open and arthroscopic techniques are similar and should not be the sole determining factor in selecting either technique.

Reactive tenosynovitis may occur after any arthroscopic procedure, although not commonly. Reports of this complication after wrist arthroscopy are rare. One study evaluating the complications of wrist arthroscopy not limited to ganglionectomy reviewed 210 cases and found “extensor tendon irritation” in only 4 cases.9 There has been only one report of extensor tenosynovitis after arthroscopic ganglion resection; in that series, it occurred in 6% of patients. This higher incidence was attributed to the extensive capsulotomy required during ganglion excision that does not occur during other arthroscopic procedures. In any case, the risk of extensor synovitis should be part of the preoperative discussion with patients.

1. Osterman AL, Raphael J. Arthroscopic resection of dorsal wrist ganglion of the wrist. Hand Clin. 1995;11:7-12.

2. Ho PC, Griffiths J, Lo WN, et al. Current treatment of ganglion at the wrist. J Hand Surg. 2001;6:49-58.

3. Rizzo M, Berger RA, Steinman SP, Bishop AT. Arthroscopic resection in the management of dorsal wrist ganglion: results with a minimum 2-yr follow-up period. J Hand Surg. 2004;29:59-62.

4. Edwards SG, Johansen JA. Prospective outcomes and associations of wrist ganglion cysts resected arthroscopically. J Hand Surg. 2009;34:395-400.

5. Povlsen B, Peckett WR. Arthroscopic findings in patients with painful wrist ganglia. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2001;35:323-328.

6. Singh D, Culp R. Arthroscopic ganglion excisions. Presented at the American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH) meeting, Phoeniz, Ariz; 2002.

7. Mathoulin C, Hoyos A, Pelaez J. Arthroscopic resection of wrist ganglia. Hand Surg. 2004;9:159-164.

8. Kang L, Akelman E, Weiss AP. Arthroscopic versus open dorsal ganglion excision: a prospective, randomized comparison of rate of recurrence and of residual pain. J Hand Surg. 2008;33:471-475.

9. Beredjiklian PK, Bozenka DJ, Leung YL, Monaghan BA. Complications of wrist arthroscopy. J Hand Surg. 2004;29:406-411.

10. Geissler WB, Freeland AE, Savoie FH, et al. Intracarpal soft-tissue lesions associated with an intra-articular fracture of the distal end of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:357-365.