CHAPTER 13 Arthroscopic Dorsal Radiocarpal Ligament Repair

Introduction

In recent years, various investigators have highlighted the role of the dorsal radiocarpal ligament (DRCL) in maintaining carpal stability.1–4 Tears of the DRCL have been linked to the development of both volar and dorsal intercalated segmental instabilities and may be implicated in the development of midcarpal instability.5–7 The existence of a DRCL tear when combined with a scapholunate interosseous ligament (SLIL) tear connotes a greater degree of carpal instability. This has been acknowledged by some authors, who have advocated an open SLIL repair versus arthroscopic pinning when there is an associated DRCL tear.8 An isolated tear of the dorsal radiocarpal ligament can also be a source of chronic wrist pain.9

In most series, the DRCL is overlooked during the typical arthroscopic examination of the wrist. It is difficult to visualize a DRCL tear through the standard dorsal wrist arthroscopy portals because the torn edge of the DRCL tends to float up against the arthroscope while viewed through the 3/-,4 portal and 4/-5 portals, which makes both identification and repair of the DRCL tear cumbersome. It can be seen obliquely through the 1/-,2 or 6-U portals, but visualization of the DRCL across the radiocarpal joint may be laborious in a tight or small wrist—especially if synovitis is present. Wrist arthroscopy through a volar radial portal (VR) is the ideal way to assess the dorsal radiocarpal ligament due to the straight line of sight10–12 (see chapter on arthroscopic portals).

Indications

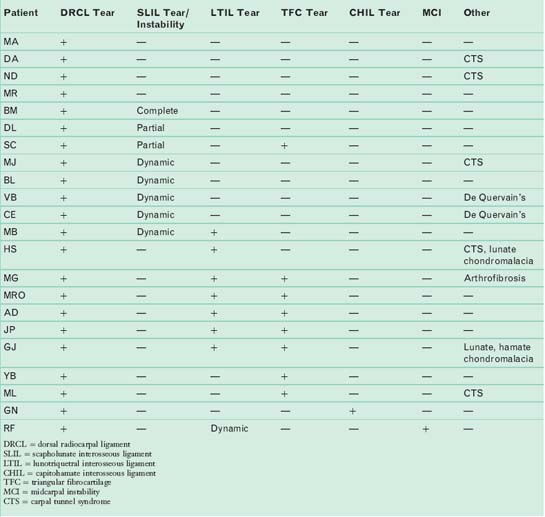

A classification system for DRCL tears was devised based on the presence or absence of associated carpal pathology (Table 13.1). Each successive stage denotes a longer-standing and/or more severe condition that negatively impacts the prognosis.

Table 13.1 Classification of Dorsal Radiocarpal Ligament Tears

| Stage I | Isolated DRCL tear |

| Stage II | DRCL tear with associated SLIL ± LTIL (Geissler I/II) ± TFCC tear |

| Stage IIIA | DRCL tear with associated SLIL ± LTIL (Geissler III) ± TFCC tear |

| Stage IIIB | DRCL tear with associated SLIL ± LTIL (Geissler IV) ± TFCC tear |

| Stage IV | Chondromalacia with widespread carpal pathology |

The ligament with the highest Geissler grade determines the stage.

DRCL – dorsal radiocarpal ligament

SLIL – scapholunate interosseous ligament

LTIL – lunotriquetral interosseous ligament

TFCC – triangular fibrocartilage complex

An arthroscopic DRCL repair is indicated for stage I, or isolated DRCL tears due to the favorable outcomes that can be achieved.9,13,14 Geissler grade I and II SLIL and/or LTIL ligament injuries are still amenable to arthroscopic treatment. DRCL repairs are also indicated in Geissler grade I and II injuries since repair of a secondary stabilizer may augment the coronal plane stability (Table 13.2). Thermal shrinkage of the ST ligaments can theoretically augment sagittal plane stability of the scapholunate joint. This can be accomplished arthroscopically and is currently under investigation, but no data is available to recommend this procedure as yet. Grade III ligament injuries represent a relative gray area. They can be successfully treated with thermal shrinkage and pinning, which should be augmented with a DRCL repair, but if this is combined with instability of the ulnocarpal joint due to a large TFCC tear and/or Geissler III ligament tear there is a high risk of failure following arthroscopic treatment alone. Grade IV ligament injuries are beyond the realm of arthroscopic treatment and require open repair or reconstruction. Due to the frequent association of DRCL tears when there is a TFCC tear, I would also recommend a DRCL repair if the TFCC tear is treated arthroscopically.

Table 13.2 Algorithm for Treatment of DRCL Tears

| Stage I | Arthroscopic DRCL repair |

| Stage II | Arthroscopic DRCL repair, SLIL or LTIL debridement ± shrinkage, TFCC repair/debridement |

| Stage IIIA | Arthroscopic DRCL repair, SLIL/LTIL shrinkage + pinning, TFCC repair/debridement ± wafer (consider STT shrinkage) |

| Stage IIIB | Open SLIL repair/reconstruction ± capsulodesis, LTIL repair/reconstruction, TFC repair/debridement ± wafer/ulnar shortening |

| Stage IV | Partial carpal fusion vs. PRC |

DRCL – dorsal radiocarpal ligament

SLIL – scapholunate interosseous ligament

LTIL – lunotriquetral interosseous ligament

PRC – proximal row carpectomy

Contraindications

When the treatment of an SLIL tear or dynamic scapholunate instability includes some type of dorsal capsulodesis, the dorsal incision followed by the creation of a dorsal capsular check-rein to restrain palmar flexion of the scaphoid renders any separate treatment of the DRCL tear unfeasible. When the DRCL tear is seen in association with palmar midcarpal instability (MCI), a soft-tissue repair of the dorsal ligaments will not by itself correct the MCI.15,16

Clinical Studies

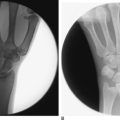

A retrospective chart review was performed of patients who underwent diagnostic wrist arthroscopy with the use of a volar radial portal.13,14 This identified 53 patients (56 wrists) over a six-year period. Additional pathology was seen in 24 patients that was not visible from the standard dorsal portals. This included 22 patients with tears of the dorsal radiocarpal ligament. Static wrist radiographs were obtained for all patients. Radiographs included a neutral-rotation posteroanterior view and a lateral view. None of the wrists showed a static carpal instability pattern. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed under the direction of the referring physician in six patients. Preoperative arthrograms were performed as a part of the diagnostic work-up for wrist pain in 20 patients.

There were 6 men and 16 women. The average patient age was 40 years (range 25 to 62 years). All patients failed a trial of conservative treatment with wrist immobilization, cortisone injections, and work restrictions. The average length of conservative treatment was seven months. The time interval between injury and surgical intervention averaged 25 months (range 8 to 53 months). At the time of arthroscopy, four patients were found to have an isolated DRCL tear that was solely responsible for their wrist pain. The remaining 17 patients had additional ligamentous pathology, summarized in Table 13.3. A dorsal capsulodesis was performed in seven patients as the primary treatment for derangements of the SLIL.

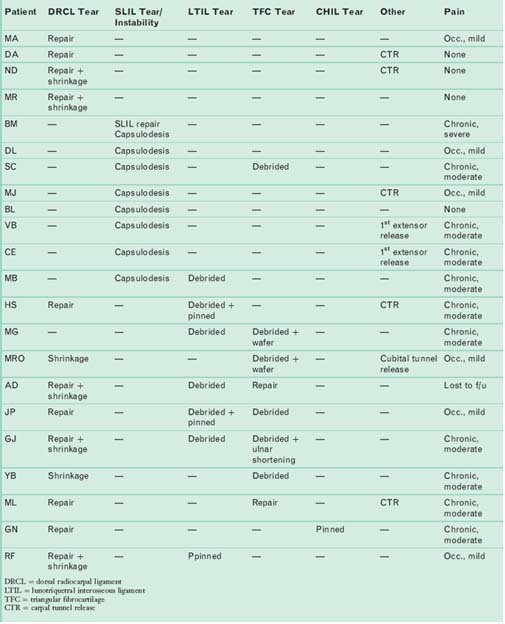

Thirteen of the 21 patients underwent an arthroscopic DRCL ligament repair and/or thermal shrinkage (repair = 5, repair + shrinkage = 6, shrinkage = 2), as described in material following. Ten of these patients underwent ancillary procedures for treatment of the coexisting wrist pathology. Lunotriquetral tears were treated with debridement and pinning. Triangular fibrocartilage tears were debrided or repaired. Scapholunate ligament tears or instability was treated with capsulodesis ± repair. One patient had generalized arthrofibrosis (MG), which precluded a DRCL repair. Concomitant nerve entrapment was a common finding, which was treated at the same time.

The average duration of the follow-up period was 16 months (range 7 to 41 months), with one patient lost to follow-up at four weeks. Pain was graded as none, mild, moderate, and severe.17 Wrist extension, wrist flexion, radial deviation, ulnar deviation, and grip strength were assessed. Wrist range of motion was compared with presurgical values. Grip strength was compared with the contralateral side at follow-up evaluation.

Patient outcomes are summarized in Table 13.4. The four patients who underwent an isolated DRCL repair were satisfied with the outcome of surgery and would repeat the surgery again because it improved their symptoms. All four patients graded their pain as none or mild. None of these patients were taking pain medications. All returned to their previous occupations without restriction. Their wrist motion was unchanged compared to the preoperative status. Grip strengths were 90 to 130% of the opposite side. The wide variety of ancillary procedures in the remaining patients and the small numbers in each subgroup precluded any statistical analysis of the possible influence of the DRCL repair on wrist motion and grip strengths.

A dorsal capsulodesis was performed as the primary treatment for an SLIL tear or a dynamic scapholunate instability in seven patients instead of a DRCL repair. This remains a popular treatment method for both static and dynamic scapholunate instability. The presence of a DRCL tear did not preclude a good result (none or mild pain) in 3/7 patients. The capsulodesis was ineffective in controlling pain in the remaining four patients, three of whom had additional wrist pathology. This is consistent with other studies, which have demonstrated that although pain is improved it does not completely resolve following a dorsal capsulodesis in the majority of cases.18

Cadaver studies suggest that dynamic scaphoid instability results from an isolated injury to the SLIL without damage to the dorsal intercarpal and DRCL ligaments.4 The author has found the corollary to hold true in that 4/7 patients with dynamic scapholunate instability had a DRCL tear but an intact scapholunate ligament. The diagnosis of dynamic carpal instability in these patients hinged upon the demonstration of the abnormal kinematics and increased motion at the scapholunate joint. This easily allowed insertion of a 3-mm probe between the scaphoid and the lunate when viewed from the midcarpal joint (i.e., Geissler grade III19), yet there was no apparent scapholunate ligament tear while probing from the radiocarpal joint.

Clinical Relevance

The true incidence of dorsoradiocarpal ligament tears is not known. It is difficult to detect a DRCL tear with nonoperative methods. It is possible that a number of patients presenting with dorsal wrist pain may be misidentified as having dorsal wrist syndrome20 or an occult dorsal wrist ganglion. DRCL tears are poorly seen through an open approach. Although seven patients who underwent a dorsal capsulodesis for scapholunate instability were found to have a DRCL tear during wrist arthroscopy, none of these tears could be identified through a dorsal capsulotomy. This may be partly because the capsular ligaments are best seen from within the wrist joint, or that the DRCL is divided during the surgical approach for a dorsal capsulodesis.

DRCL tears appear to be part of a spectrum of radial and ulnar-sided carpal instability. It is instructive to consider the wrist as having a number of primary and secondary stabilizers. The SLIL, LTIL, and TFC are the primary stabilizers. The capsular ligaments (including the radioscaphocapitate, radiolunotriquetral, ulnolunate, ulnotriquetral, dorsal radiocarpal, and dorsal intercarpal ligaments) can be thought of as secondary stabilizers. A chronic tear of a primary stabilizer may culminate in the attenuation or tearing of the secondary stabilizer. This is seen in patients with long-standing triquetrolunate dissociation of more than six months duration. Arthroscopy in these cases often reveals fraying of the ulnolunate ligaments and ulnotriquetral ligaments.21 In the previously referenced series, there was a frequent association of a DRCL tear with either an SLIL or LTIL/TFC tear.

Injury to the DRCL has been implicated in palmar midcarpal instability (MCI).5,6,15 Soft-tissue repairs of the dorsal ligaments alone appear to be insufficient to correct this type of carpal instability.15,16 Goldfarb et al. reported on one patient with palmar MCI in whom a diffuse tear involving the dorsal ligaments was shown on a preoperative MRI. A repair of the dorsal ligaments failed to relieve the patient’s symptoms and a midcarpal fusion was ultimately performed.17 Palmar MCI was seen in one patient in the author’s series, which did not resolve following LTIL pinning and a DRCL repair.

The cause of wrist pain with isolated capsular ligament tears is not entirely clear. In nondissociative carpal instability the pain is believed to be due to dynamic joint incongruity.22 Chronic impingement of a detached ulnar sling on the triquetrum has been implicated as a cause of wrist pain.23 It is plausible that tears of the DRCL may cause pain through their deleterious effects on carpal stability or through impingement of the torn edge of the DRCL against the lunate. Repair of an isolated tear of a capsular ligament can alleviate wrist pain. This has been demonstrated with repairs of ulnolunate ligament tears.24,25 All four of the patients with an isolated DRCL tear also had a favorable response to arthroscopic repair. Slater et al. demonstrated that the dorsal wrist ligaments have a constant blood supply.26 The implication of their work is that tears of the DRCL have the potential to heal. This provides a rationale for arthroscopic repair of a DRCL tear.

Arthroscopic ligament plication for combined LTIL and TFC tears has been previously reported.27 The DRCL repair as described stabilizes the torn edge by plicating it to the dorsal capsule, but it does not necessarily restore the integrity of the ligament per se. Its ameliorating effect on wrist pain may act by forestalling impingement on the lunate or by normalizing carpal kinematics, but there is a lack of biomechanical data to support these theories. Thermal shrinkage was added in some patients in an effort to shorten a voluminous DRCL when sutures alone were ineffective.

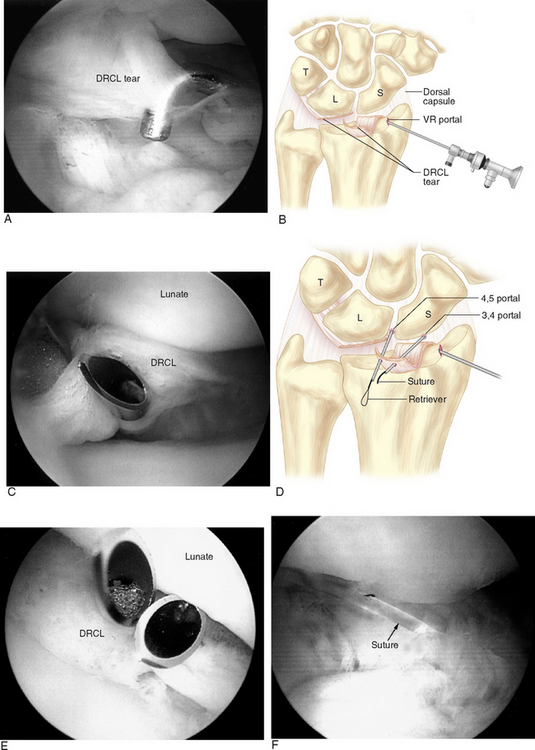

Surgical Technique

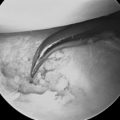

An inside-out arthroscopic repair technique of the DRCL is performed through a volar radial (VR) wrist arthroscopy portal that allows a direct line of sight with the dorsal radiocarpal ligament (Figure 13.1a). A 2-cm longitudinal incision is made in the proximal wrist crease, exposing the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendon sheath. The sheath is divided and the FCR tendon retracted ulnarly. The radiocarpal joint space is identified with a 22-gauge needle and the joint inflated with saline. A blunt trochar and cannula are introduced through the floor of the FCR sheath, which overlies the interligamentous sulcus between the radioscaphocapitate ligament and the long radiolunate ligament.

A 2.7-mm 30 degree arthroscope is inserted through the cannula. A meniscus repair cannula is then inserted adjacent to the arthroscope. In a small wrist, the capsular intervals on either side of the long radiolunate ligament can be used. While visualizing the DRCL tear through the VR portal, a 2–0 absorbable suture on double-armed straight needles is introduced through the meniscal repair cannula. The needles are passed across the radiocarpal joint through the torn edge of the DRCL, exiting through the floor of the fourth extensor compartment (Figure 13.1b through e). One or two horizontal mattress sutures are inserted in this fashion. A small dorsal incision is made to retrieve the sutures before tying, to ensure there is no extensor tendon entrapment.

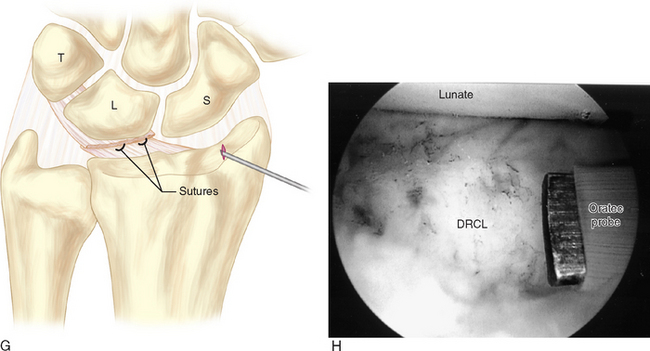

An outside-in repair is technically easier and has been used more recently. The repair is performed by spearing the radial side of the DRCL tear with a curved 21-gauge spinal needle placed through the 3/-,4 portal while viewing through the arthroscope, which is inserted in the VR portal. A 2–0 absorbable suture is threaded through the spinal needle and retrieved with a grasper or suture snare inserted through the 4/-,5 portal (Figure 13.2a through f). A curved hemostat is used to pull either end of the suture underneath the extensor tendons, and the knot is tied either at the 3/-,4 or 4/-,5 portal. The repair is augmented with thermal shrinkage if the torn edge of the DRCL is voluminous and still protrudes into the joint after the sutures are tied (Figure 13.2g).

1 Mitsuyasu H, Patterson RM, Shah MA, et al. The role of the dorsal intercarpal ligament in dynamic and static scapholunate instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2004;29:279-288.

2 Short WH, Werner FW, Green JK, Weiner MM, Masaoka S. The effect of sectioning the dorsal radiocarpal ligament and insertion of a pressure sensor into the radiocarpal joint on scaphoid and lunate kinematics. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2002;27:68-76.

3 Viegas SF, Yamaguchi S, Boyd NL, Patterson RM. The dorsal ligaments of the wrist: Anatomy, mechanical properties, and function. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999;24:456-468.

4 Ruch DS, Smith BP. Arthroscopic and open management of dynamic scaphoid instability. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;32:233-240.

5 Horii E, Garcia-Elias M, An KN, et al. A kinematic study of luno-triquetral dissociations. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1991;16:355-362.

6 Viegas SF, Patterson RM, Peterson PD, et al. Ulnar-sided perilunate instability: An anatomic and biomechanic study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1990;15:268-278.

7 Moritomo H, Viegas SF, Elder KW, et al. Scaphoid nonunions: A 3-dimensional analysis of patterns of deformity. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2000;25:520-528.

8 Ruch DS, Poehling GG. Wrist arthroscopy: Ligamentous instability. In: Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, editors. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. Fourth Edition. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:200-206.

9 Slutsky DJ. Arthroscopic repair of dorsal radiocarpal ligament tears. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:E49.

10 Slutsky DJ. Wrist arthroscopy through a volar radial portal. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:624-630.

11 Slutsky DJ. Volar portals in wrist arthroscopy. Journal of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. 2002;2:225-232.

12 Slutsky DJ. Clinical applications of volar portals in wrist arthroscopy. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2004;8(4):229-238.

13 Slutsky DJ. Arthroscopic repair of dorsoradiocarpal ligament tears. The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2005;21:1486e1. 1486e8

14 Slutsky DJ. Management of dorsoradiocarpal ligament repairs. Journal of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. 2005;5:167-174.

15 Lichtman DM, Bruckner JD, Culp RW, Alexander CE. Palmar midcarpal instability: Results of surgical reconstruction. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1993;18:307-315.

16 Wright TW, Dobyns JH, Linscheid RL, Macksoud W, Siegert J. Carpal instability non-dissociative. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1994;19:763-773.

17 Goldfarb CA, Stern PJ, Kiefhaber TR. Palmar midcarpal instability: The results of treatment with 4-corner arthrodesis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2004;29:258-263.

18 Moran SL, Cooney WP, Berger RA, Strickland J. Capsulodesis for the treatment of chronic scapholunate instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:16-23.

19 Geissler WB, Freeland AE, Savoie FH, McIntyre LW, Whipple TL. Intracarpal soft-tissue lesions associated with an intra-articular fracture of the distal end of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:357-365.

20 Watson HK, Weinzweig J. Physical examination of the wrist. Hand Clin. 1997;13:17-34.

21 Zachee B, De Smet L, Fabry G. Frayed ulno-triquetral and ulno-lunate ligaments as an arthroscopic sign of longstanding triquetro-lunate ligament rupture. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1994;19:570-571.

22 Bednar JM, Osterman AL. Carpal instability: Evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:10-17.

23 Watson HK, Weinzweig J. Triquetral impingement ligament tear (tilt). J Hand Surg [Br]. 1999;24:321-324.

24 Osterman AL. Wrist arthroscopy: Operative procedures. In: Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, editors. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. Fourth Edition. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:207-222.

25 Mooney JF, Poehling GG. Disruption of the ulnolunate ligament as a cause of chronic ulnar wrist pain. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1991;16:347-349.

26 Slater RR, Jr., Safian CC, Laubach JE. Vascular anatomy of the dorsal wrist ligaments. Presented at the Fifty-fifth Annual Meeting of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, Seattle, Washington, 2000.

27 Moskal MJ, Savoie FHIII, Field LD. Arthroscopic capsulodesis of the lunotriquetral joint. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:141-153.