CHAPTER 9 Arthroscopic Distal Clavicular Resection

ANATOMY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The acromioclavicular joint is subcutaneous and exposed to substantial biomechanical forces during shoulder motion. It is therefore susceptible to degenerative processes and acute trauma. Located between the distal end of the clavicle and the anteromedial aspect of the acromion, the AC joint is a diarthrodial joint. The joint is initially composed of hyaline cartilage articulations incompletely separated by a fibrocartilaginous disk1; however, it undergoes degeneration to fibrocartilage by 40 years.1

Although the exact dimensions are debated, the average size of the adult acromioclavicular joint is approximately 9 mm in the coronal plane and 19 mm in the sagittal plane.2 There is tremendous variability in the coronal orientation of the joint.1,3 Three coronal orientations have been described: an overriding clavicle (the clavicle overrides the acromion), a neutral AC joint, and an underriding clavicle (the acromion overrides the clavicle).4 The overriding clavicle is the most common variant, occurring in almost 50% of individuals.5

The CC ligaments include the medial conoid and lateral trapezoid ligaments; however, up to 1% of patients have a coracoclavicular bar.6 The average distance between the clavicle and coracoid is from 11 to 13 mm.2,7 The CC ligaments are extracapsular and the average distance from the most lateral extent of the trapezoid ligament fibers to the joint is 15.3 mm (range, 11 to 22 mm).8 The CC ligaments are the primary constraints to superior and inferior translation, whereas the AC ligaments and capsule are the primary restraints to anteroposterior instability. However, the AC and CC ligaments have a dynamic interplay, whose contributions to stability vary with the directions and forces applied.9

Given its anatomy, the potential motion of the AC joint far exceeds that actually demonstrated during active motion of the shoulder girdle.10 Actually, very little motion occurs at the AC joint in comparison to that of the sternoclavicular joint; less than 10 degrees of rotation occur at the AC joint with full elevation of the arm.11

MECHANISM OF INJURY

Acromioclavicular joint pathology can be stratified into two broad categories, instability and arthritic conditions. Either condition may be the sequel of direct or indirect forces applied to the upper extremity. Direct forces are the most common mechanism of injury, resulting from a fall on the point of the shoulder, usually with the arm adducted. Indirect forces may be transmitted through the upper extremity and dissipated within the acromioclavicular articulation, leading to ligamentous and cartilaginous injury. These forces may lead to an acute injury or, with chronic degeneration, an arthritic condition. An isolated subset of the arthritic population is the younger athlete or weightlifter whose repetitive exercises have induced a stress reaction in the distal clavicle, known as distal clavicular osteolysis. Instability may also be iatrogenic, caused by an overzealous previous distal clavicle resection.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Whereas pain arising in the AC joint is often localized to the anterosuperior aspect of the shoulder, referred pain may exist, given the rich innervation of the joint by the suprascapular, lateral pectoral, and axillary nerves. With injection studies, Gerber and colleagues12 have demonstrated that patients may complain of pain distributed over the anterolateral neck, posterior trapezius, and anterolateral deltoid. Painful motions will often include cross-body adduction, overhead activities, internal rotation, and extension of the arm behind the plane of the scapula. Common complaints are pain while putting on a coat, strapping a bra, or washing the contralateral axilla. Weightlifters and athletes with distal clavicular osteolysis describe soreness and pain with flat and inclined bench presses, shoulder presses, and dips. Special attention should be paid to patients in whom a previous distal clavicular resection has been performed. These patients may present for inadequate resection, instability, or a missed diagnosis.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING OF ACROMIOCLAVICULAR JOINT PATHOLOGY

If AC joint stability is in question, an AP of bilateral shoulders including the AC joints should be taken to compare the coracoclavicular distances with the identical tangential view. Stress views may also be obtained, but are not usually required.13

Magnetic resonance imaging is not typically necessary for diagnosing acromioclavicular pathology; however, it is useful to evaluate for masses or cysts about the AC joint and concomitant shoulder pathology that may need to be addressed. Unfortunately, findings of increased T2 signal intensity can be nonspecific for symptomatic pathology14 and therefore must be correlated with physical findings that support the diagnosis of AC pathology.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Depending on the severity and duration of symptoms, distal clavicle arthrosis may be treated with conservative or surgical modalities. With mild to moderate symptoms that do not dramatically alter a patient’s activities of daily life, it is prudent to begin with activity modifications. Weightlifters and athletes may be able to alter their workout regimen to decrease stress across the AC joint. A local injection of corticosteroid inside the AC joint has a dual purposed; it is not only diagnostic, but also therapeutic.15 The anesthetic helps the clinician determine what percentage of shoulder pain and dysfunction is directly attributable to AC pathology. The corticosteroid injection may break the cycle of inflammation and allow for resumption of activities. In our experience, physical therapy does not dramatically alter the natural history or symptoms of AC joint arthrosis; however, it may alleviate concomitant rotator cuff–based symptoms.

Since 1941, when conservative management was shown to not be effective, distal clavicle excision has proven itself as a successful surgical intervention for AC arthrosis.16 Distal clavicle resection may be accomplished through an open or arthroscopic approach. Open distal clavicle resection requires detachment and subsequent repair of the deltotrapezial fascia from the clavicle. Arthroscopic distal clavicle management has been shown to provide reliable results17,18 with a less invasive approach than open techniques,19,20 and may be performed in conjunction with the arthroscopic management of other shoulder pathology.

Arthroscopic Distal Clavicle Resection

Indications and Contraindications

The indications for operative intervention vary with pathologic entity. Our discussion will not include acromioclavicular dislocations, in which ligamentous damage may require reconstruction and the clavicle may require stabilization. Care must be taken to pick up subtle (e.g., grade 2 injuries) cases. We have found AP drawer testing, often after an anesthetic injection, more reliable than comparison weight-bearing views. Confining this discussion to arthritic conditions, surgical intervention may be considered once conservative management has failed. AC arthritis and distal clavicular osteolysis are self-limiting diseases and therefore should not be considered until the patient cannot tolerate their pain and/or disability. AC symptoms that fail conservative management can be managed effectively with arthroscopic distal clavicle resection through a subacromial or direct superior approach.17,18 Patients with prior failed AC resection may also be managed with revision arthroscopic débridement if bony impingement or inadequate resection is confirmed by imaging and clinical evaluation. However, in some cases, especially when associated AC instability is evident or when lesions such as large AC cysts are present, open resection and reefing of the superior ligaments and deltotrapezial fascia may be indicated. Such scenarios may represent relative contraindications to arthroscopic management.

Techniques

Basic Arthroscopic Setup.

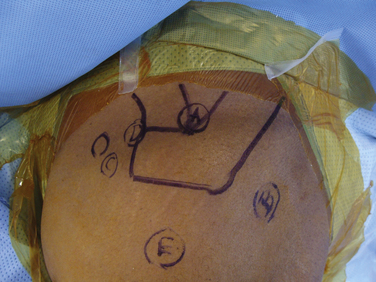

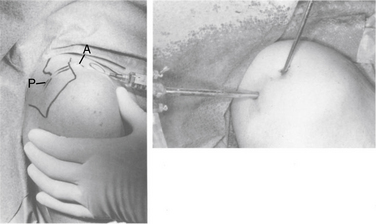

Arthroscopic distal clavicle resection may be completed in the lateral or beach chair position; the choice should be predicated on concomitant shoulder pathology and surgeon comfort. Standard arthroscopic instruments, including a 4.2-mm motorized shaver, 4.0 acromionizer burr, and arthroscopic cautery, are used. The forequarter is draped free, with care taken to ensure access to the AC joint. Osseous landmarks are marked on the skin and the AC joint is delineated with localization confirmed by needle placement (Fig. 9-1).

Bursal Approach.

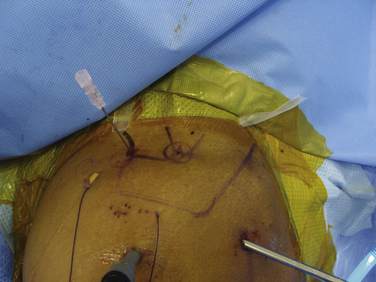

Once prepped and draped, a routine shoulder arthroscopy is begun. A standard posterior portal is created in the posterior soft spot (see Fig. 9-1). There are two options for anterior portals In anticipation of AC débridement, the standard anterior portal can be made in line with the demarcated AC joint to enable glenohumeral access via the rotator interval and access to the AC joint. Alternatively, the standard anterior portal in the rotator interval can be established, and a separate anterior accessory portal can be established for ease of decompression.21

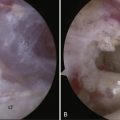

The next step is to identify the AC joint; this is completed with needle localization or by manually depressing the distal clavicle. Pressing on the distal clavicle effectively delivers more of the clavicle inferior to the acromion, thereby aiding in visualization from the subacromial space. Placement of a needle in the AC joint may help with identification of the joint arthroscopically and externally, as a triangulation landmark (Figs. 9-2 and 9-3). Cautery is used to strip the inferior AC capsule off the AC joint.

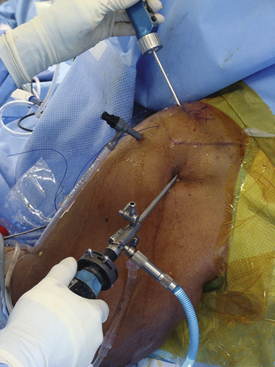

While visualizing from the posterior portal with a 30-degree arthroscope and superolaterally oriented optics, either the anterior portal or accessory anterior portal is used as a working portal into the anterior AC joint. If an accessory portal is to be used, it is localized along the anterosuperior aspect of the AC joint, and may enable ease of working within the AC joint21 (see Figs. 9-2 and 9-3). The in-line vector of a properly placed anterior or accessory anterior portal enables the burr to be controlled with uniplanar vertical sweeping motions (Fig. 9-4).

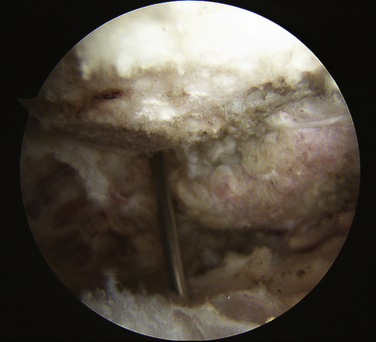

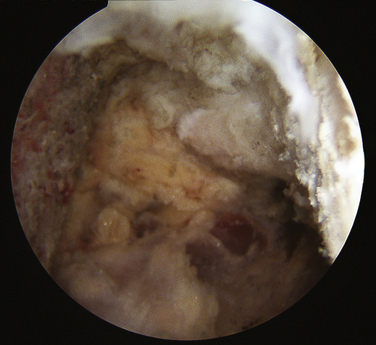

Soft tissue within the AC joint is removed with a motorized shaver or cautery exposing the distal clavicle. Care is taken to expose the superior anterior and posterior corners of the joint while retaining the superior AC ligament and/or capsule. Once exposure is obtained, the distal clavicle is resected with a motorized burr in a sequential fashion from anteroinferior to posterosuperior via the anterior portal. In general, 8 to 10 mm of distal clavicle is resected to enable sufficient resection and relieve any bony impingement while ensuring preservation of the medial CC ligaments.22

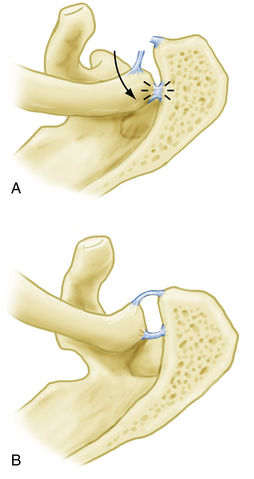

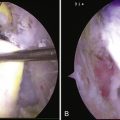

During resection, it is imperative to preserve the superior ligaments to prevent iatrogenic anterior and posterior instability and to address the posterosuperior corner of the clavicle (Fig. 9-5). This area is the most common underresected portion of the clavicle. We routinely switch our arthroscope to the anterior accessory portal to visualize our resection at the completion of our resection (Fig. 9-6). In rare cases, an accessory posterosuperior portal may be needed to resect the posterosuperior distal clavicle fully, especially early in a surgeon’s learning curve.

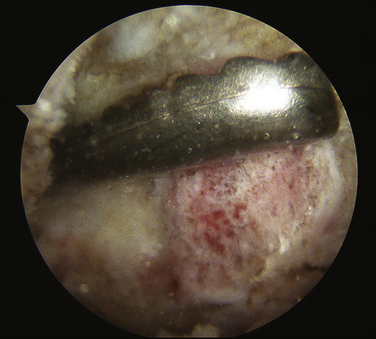

Once the resection is completed, a symmetrical and adequate resection is confirmed by measuring with an instrument of known dimensions. At our institution, we use a rasp measuring 8 mm in width, which must easily fit into the new joint space (Fig. 9-7).

Direct Approach.

A direct superior arthroscopic approach is indicated in patients with isolated AC pathology, most frequently in cases of distal clavicular osteolysis.17,20 The direct approach avoids violation of the subacromial space and bursa and therefore may be less traumatic in select patients. However, patients typically present with concomitant subacromial and AC pathology, and therefore are more frequently managed via a bursal approach to the AC joint.

Portals are identified along the anterior and posterior line of the AC joint, 0.5 cm from the joint edge (Fig. 9-8; see Fig. 9-2). The posterior portal is developed bluntly and the arthroscope is introduced into the posterior AC joint. The location of the anterior portal is then confirmed with needle localization and developed. Electrocautery or a motorized shaver is used to remove intra-articular tissue and visualize the AC joint. Careful dissection with cautery is then performed to visualize the anteroinferior and anterosuperior corners of the AC joint. The superior AC ligament and capsule should be left intact and not be violated.

Using the burr, the anterior distal clavicle is resected in a sequential fashion, from inferior to superior, and then progressing more posteriorly. Care is taken to ensure a smooth osseous resection without ridges and the superior corner of the clavicle must be visualized. The arthroscope is then switched to the anterior portal to allow for improved posterior joint visualization. The previously resected anterior clavicle serves as a template for posterior resection. In general, a minimum of 8 to 10 mm of bone is resected to ensure no persistent bony impingement. The anterior and posterior superior corners are carefully visualized to ensure no persistent ridges or overhangs of bone remain. Similar to the bursal approach, at the end of the resection, we use an 8-mm rasp brought into the joint to confirm appropriate resection width (see Fig. 9-6).

Closure and Postoperative Protocol.

At the conclusion of the procedure, the joint is irrigated and bony debris removed with a motorized shaver. Hemostasis is obtained. Portals are closed with buried absorbable simple sutures and the skin is dressed with adhesive strips and sterile dressing. The arm is placed in a sling for comfort. In cases of isolated AC pathology, patients are started on a gentle active and passive therapy protocol to minimize postoperative stiffness. Patients are seen at approximately 2, 6, and 12 weeks from surgery. At 2 weeks, the wounds are inspected and range of motion is examined. By 4 to 6 weeks, the soft tissues have healed and patients may resume all activities, although we encourage delay of heavy lifting or weight training, especially bench presses, until 3 months to avoid stretching weakened AC ligaments.

RESULTS OF ARTHROSCOPIC DISTAL CLAVICLE EXCISION

Arthroscopic distal clavicle resection has established an extremely successful and predicable track record in patients with preoperatively stable, arthritic AC joints.17,20–24 Arthroscopic resection enjoys the same excellent long-term pain relief as open resection, but the benefits of less soft tissue violation and a faster return to painless full range of motion and athletic activities. With meticulous surgical technique and exacting attention paid to a smooth even resection, surgeons can expect good to excellent outcomes in 88% to 100% of patients with isolated acromioclavicular arthrosis.18,21,25

1. Depalma AF. Surgical anatomy of acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints. Surg Clin North Am. 1963;43:1541-1550.

2. Bosworth BM. Complete acromioclavicular dislocation. N Engl J Med. 1949;241:221-225.

3. DePalma AF. Surgical anatomy of the rotator cuff and the natural history of degenerative periarthritis. Surg Clin North Am. 1963;43:1507-1520.

4. Moseley HF. Athletic injuries to the shoulder region. Am J Surg.. Sep 1959;98:401-422.

5. Keats TE, Pope TLJr The acromioclavicular joint: normal variation and the diagnosis of dislocation. Skeletal Radiol, 17; 1988:159-162.

6. Lewis OJ. The coraco-clavicular joint. J Anat. Jul 1959;93:296-303.

7. Bearden JM, Hughston JC, Whatley GS Acromioclavicular dislocation: method of treatment. J Sports Med, 1; 1973:5-17.

8. Harris RI, Vu DH, Sonnabend DH, et al. Anatomic variance of the coracoclavicular ligaments. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. Nov-Dec 2001;10:585-588.

9. Fukuda K, Craig EV, An KN, et al. Biomechanical study of the ligamentous system of the acromioclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Mar 1986;68:434-440.

10. Rockwood CAJr, Matsen FAIII, Wirth MA, Lippitt SB, editors. The Shoulder, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2004.

11. Rockwood CAJr. Fractures in Adults. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996.

12. Gerber C, Galantay RV, Hersche O. The pattern of pain produced by irritation of the acromioclavicular joint and the subacromial space. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:352-355.

13. Bossart PJ, Joyce SM, Manaster BJ, Packer SM. Lack of efficacy of ‘weighted’ radiographs in diagnosing acute acromioclavicular separation. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:20-24.

14. Stein BE, Wiater JM, Pfaff HC, et al. Detection of acromioclavicular joint pathology in asymptomatic shoulders with magnetic resonance imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:204-208.

15. Buttaci CJ, Stitik TP, Yonclas PP, Foye PM Osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular joint: a review of anatomy, biomechanics, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Phys Med Rehabil, 83; 2004:791-797.

16. Worcester JN r, Green DP. Osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;58:69-73.

17. Zawadsky M, Marra G, Wiater JM, et al Osteolysis of the distal clavicle: long-term results of arthroscopic resection. Arthroscopy, 16; 2000:600-605.

18. Kay SP, Dragoo JL, Lee R. Long-term results of arthroscopic resection of the distal clavicle with concomitant subacromial decompression. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:805-809.

19. Matthews LS, Parks BG, Pavlovich LJJr, Giudice MA Arthroscopic versus open distal clavicle resection: a biomechanical analysis on a cadaveric model. Arthroscopy, 15; 1999:237-240.

20. Flatow EL, Cordasco FA, Bigliani LU Arthroscopic resection of the outer end of the clavicle from a superior approach: a critical, quantitative, radiographic assessment of bone removal. Arthroscopy, 8; 1992:55-64.

21. Levine WN, Barron OA, Yamaguchi K, et al. Arthroscopic distal clavicle resection from a bursal approach. Arthroscopy.. Jan-Feb 1998;14:52-56.

22. Shaffer BS. Painful conditions of the acromioclavicular joint. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7:176-188.

23. Bigliani LU, Nicholson GP, Flatow EL. Arthroscopic resection of the distal clavicle. Orthop Clin North Am. 1993;24:133-141.

24. Flatow EL, Duralde XA, Nicholson GP, et al. Arthroscopic resection of the distal clavicle with a superior approach. J Shoulder Elbow Surg.. 1995;4(pt 1):41-50.

25. Martin SD, Baumgarten TE, Andrews JR. Arthroscopic resection of the distal aspect of the clavicle with concomitant subacromial decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:328-335.