CHAPTER 12 Arthroscopic and Open Radial Ulnohumeral Ligament Reconstruction for Posterolateral Rotatory Instability of the Elbow

Dysfunction of the lateral ligamentous complex of the elbow may produce considerable dysfunction in the activities of daily living.1 Unlike the medial ulnar collateral ligament, whose injury results in disability during athletic activities, the radial ulnohumeral ligament (RUHL) complex is involved in even the simplest activities of the upper extremity. There has been a growing interest in the diagnosis and treatment of posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI) of the elbow since the original description by O’Driscoll and colleagues in 1991.1 Because the RUHL complex stabilizes the elbow during supination and extension activities, even mild injury to this area can cause difficulty in lifting and twisting activities, such as turning a key or opening a door.

ANATOMY

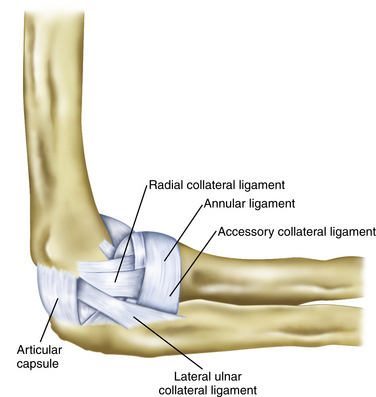

The RUHL complex as described by O’Driscoll and coworkers1 is formed by three separate components that may have a variable expression. The radial collateral ligament is adjacent to the capsule and courses from the lateral epicondyle to the annular ligament and then down to the ulna. The RUHL begins at a variable point on the posterolateral aspect of the lateral epicondyle and courses distally to the crest of the ulna while sending fibers to the annular ligament and blending with the lateral collateral ligament (Fig. 12-1). The annular ligament originates and inserts on the ulna while following a course around the radial neck.

Anatomic studies have attempted to define the involved tissue. Dunning and colleagues2 stated that the RUHL and the radial collateral ligament must be sectioned to achieve PLRI. They also found that they could not visually differentiate the two ligaments at their humeral origin. They could differentiate the RUHL from the radial collateral ligament only by identifying the distal extent of the RUHL at the supinator crest of the ulna.2 Seki and associates3 were able to show that sectioning just the anterior band of the lateral collateral complex induced instability. This suggests that an intact RUHL cannot stabilize the elbow.3 These data demonstrate that the cause of PLRI is a spectrum of injury. Although originally described as sequelae of an elbow dislocation, these anatomic studies and a report by Kalainov and Cohen4 support our own experience that there is a continuum of injury between PLRI and frank elbow dislocation.1,5

Instability findings may coexist with the standard examination findings of lateral epicondylitis, radial tunnel, and posterolateral plica syndrome. Kalainov and Cohen4 posit that PLRI may be a cause of these problems of the elbow. Twenty-five percent of patients in their study had previous surgery for chronic, recurrent lateral epicondylitis. We think that uncorrected posterolateral instability of the elbow may result in increased tension on the lateral musculature as it attempts to stabilize the elbow, thereby producing a secondary lateral epicondylitis. Other tertiary findings, such as an inflamed posterolateral plica and inflammation of the posterior interosseous nerve in or near the radial tunnel, may also occur with the instability. Physicians must look for the instability and fully evaluate the elbow of patients with all of these findings. The clinical examination recommended by O’Driscoll and colleagues1 and by Regan and Lapner6 can assist in the determination of a coexisting instability as a base cause of these problems in the elbow.

Smith and colleagues5 initially described the role of arthroscopy in treating PLRI, and there have been various anecdotal reports since then.7 In this chapter, we update and summarize the current information about the diagnosis and management of PLRI.

PATIENT EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

Instability is best demonstrated clinically with the pivot shift test of the elbow. As first described by O’Driscoll and colleagues,1 this test with the patient in the supine position may elicit gross instability or pain and apprehension.1 Two other clinical tests assess (1) pain when pushing up from an arm chair with the palms facing inward and (2) having the patient push up from a prone or wall-leaning position first with the forearms maximally pronated and then repeating the test with the forearms supinated, reproducing pain or instability, or both.6,8

Diagnostic Imaging

Imaging studies for PLRI can be helpful. Radiographs may reveal an avulsion fragment from the posterior humeral lateral epicondyle in acute cases. However, radiographic findings often are normal. A stress radiograph or fluoroscopic scan while performing the pivot shift test may show the radial head and proximal ulna moving together in a subluxated and posterolaterally rotated position. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the elbow can identify a lesion in the RUHL.9 It has been our experience that MRI is most helpful when contrast is added. This can be done for formal arthrography or, in the case of office MRI, an injection of 20 to 30 mL of sterile normal saline with or without gadolinium delivered into the olecranon fossa just before the scan can greatly enhance the effectiveness of the test.

TREATMENT

Indications and Contraindications

The indications for treatment of PLRI are the same as for any other injury: pain and functional impairment. Although much has been written about the pathologic anatomy and biomechanics of the lesion, little has been reported on the surgical treatment of these patients. Consequently, no level 1 studies comparing the effectiveness of operative or nonoperative management of this disorder have been published, nor are there any large published series describing the outcomes of the surgical treatment of PLRI. In the following sections, we review the outcomes of our experiences with arthroscopic repair, plication, and open grafting techniques.5

Arthroscopic Technique

The surgical treatment of posterolateral instability may be divided into distinct subgroups based on cause: acute dislocations, recurrent dislocations, and PLRI. The procedures used may also be divided into subgroups based on available tissue at the time of reconstruction: repair of ligamentous avulsion, plication of the RUHL complex with or without repair to bone, and tendon graft reconstruction.

Repair of Simple and Recurrent Dislocations

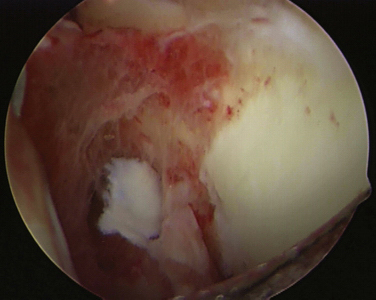

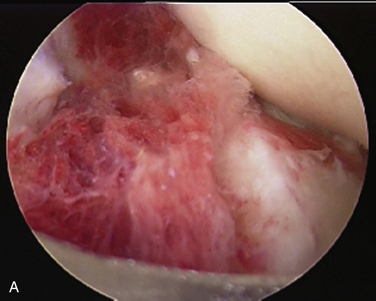

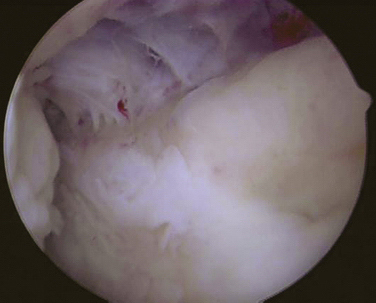

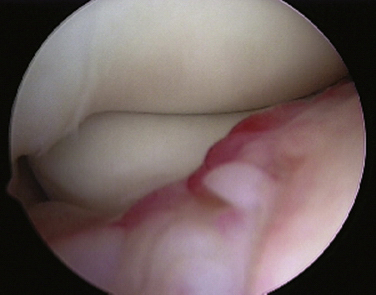

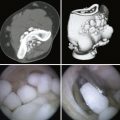

The procedure begins with establishment of a proximal anteromedial portal and diagnostic anterior compartment arthroscopy. In the acute setting, it may be necessary to establish a lateral portal to clean out the associated hematoma (Fig. 12-2). Tearing of the anterior capsule is readily apparent. In acute dislocations, the surgeon can often also see the damage to the brachialis muscle through the torn capsule (Fig. 12-3). The annular ligament should be surveyed for damage, and a suture is placed in it if necessary. The surgeon also can view around the corner of the proximal capitellum for damage to the collateral ligament part of the RUHL complex. In the acute setting, injuries to this ligament can tear the capsule in this area, and the musculature can be seen through the tear.

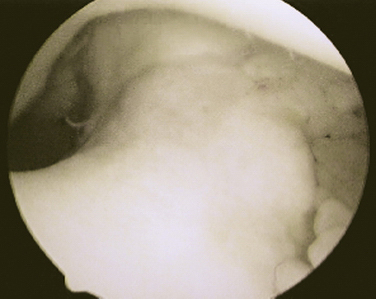

The arthroscope is placed into the posterior central portal, and the hematoma in the back of the elbow compartment evacuated through a proximal posterior lateral portal. Both portals need to be relatively proximal, usually at least 3 cm above the olecranon tip, to allow the later repair of the ligament. A view of the medial gutter shows hemorrhage and sometimes shows tearing of the capsule near the posterior aspect of the medial epicondyle (Fig. 12-4).

The lateral gutter and capsule are evaluated. It is important to stay close to the ulna as the lateral gutter is evaluated and the hematoma débrided, because the avulsed ligament and bone fragments are displaced distally and may inadvertently be removed by the shaver (Fig. 12-5). The lateral aspect of the posterior humerus should be lightly débrided and the site of avulsion localized. It is usually directly lateral and slightly inferior to the center of the olecranon fossa, and it is easily seen after the hematoma has been removed.

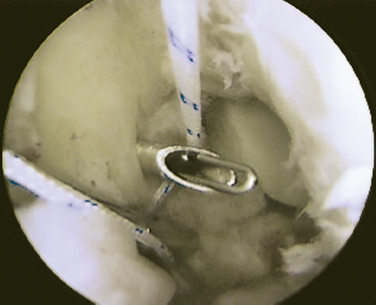

After the area of damage has been defined, an arthroscopic anchor may be placed into the humerus at the origin of the RUHL (Fig. 12-6). The limbs of the suture are retrieved to place two horizontal mattress sutures through the noninjured part of the ligament. In the case of a bony avulsion, we place one set of sutures around the bone fragment and the other distal to the fragment (Fig. 12-7). The sutures are tensioned while viewing with the arthroscope, which should have the effect of pushing the arthroscope out of the lateral gutter. The elbow is then extended, and the sutures are tied beneath the anconeus muscle, tightening the ligament. Motion and stability are then evaluated with the arthroscope in the anterior compartment (Fig. 12-8). This ligament is lax in extension and tightens with flexion. We usually recommend placing the elbow in pronation and 45 to 60 degrees of flexion during tensioning to prevent overtightening and the resultant loss of flexion.

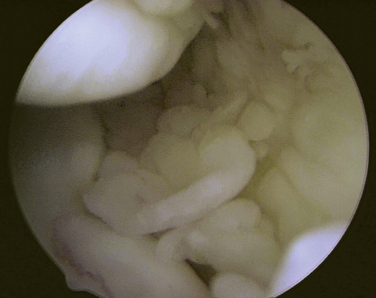

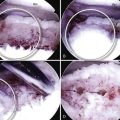

Arthroscopic Plication for Recurrent Posterolateral Rotatory Instability

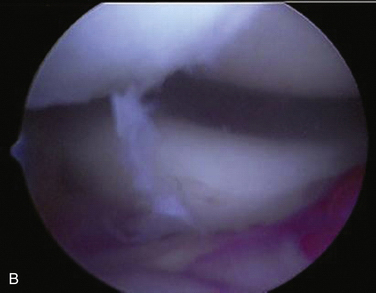

The development of arthroscopic plication for recurrent or chronic PLRI was described by Smith and colleagues in 2001.5 Chronic posterolateral instability is more readily seen during examination under anesthesia and by arthroscopic evaluation. While viewing from the proximal anteromedial portal, the ulna and radial head can be seen to subluxate posterolaterally during the performance of a pivot shift test. In most cases, the annular ligament is intact as the entire proximal radioulnar joint shifts on the humerus. A common finding is the ability to move an arthroscope placed down the posterolateral gutter from the posterior central portal straight across the ulnohumeral articulation into the medial gutter. This maneuver, called the drive-through sign, is not possible in a stable elbow. It is somewhat analogous to the drive-through sign in shoulder instability (Fig. 12-9). Elimination of this drive-through sign is one of the key aspects of confirming an adequate arthroscopic reconstruction in patients with PLRI.

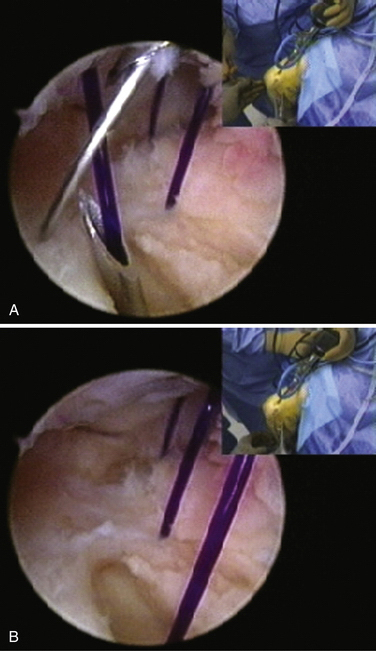

If adequate tissue is present, the tissue in the posterolateral gutter is assessed arthroscopically and prepared with a shaver or rasp. Four to seven absorbable sutures are placed in oblique fashion, beginning at the most distal extent of the RUHL complex attachment to the ulna. The sutures are placed into the lateral gutter with an 18-gauge spinal needle that slides along the radial border of the ulna. The first suture is delivered into the joint through the midportion of the annular ligament (Fig. 12-10A). Subsequent sutures are brought into the joint in a progressively more proximal position. Each suture is immediately retrieved with a retrograde suture retriever that passes into the joint from the posterolateral aspect of the lateral epicondyle (see Fig. 12-10B) using the curve of the retriever to hook under the radial collateral ligament. The retrograde retriever must come under the entire RUHL near its proximal attachment to the humerus. After all the sutures have been placed, they are retrieved one at a time percutaneously through the existing skin portals under or, in some cases, over the anconeus muscle and pulled to tension the sutures and evaluate the plication.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

Postoperative Management

Shoulder, periscapular, wrist, and hand exercises are initiated and allowed as long as they do not produce pain in the elbow. The patient is seen at 2-week intervals, and motion is slowly increased as pain and swelling allows. After the repair begins to mature, usually between 5 and 8 weeks, physical therapy is increased to include more aggressive upper extremity and core exercises with the elbow brace in place. We expect normal motion of the elbow by 8 weeks postoperatively, if not earlier. Depending on individual progression, patients are allowed to start strengthening exercises out of the brace at 10 to 12 weeks. They must be able to perform all strengthening exercises in the brace without pain before progression to exercise out of the brace.

Open Technique

The open technique for plication and repair is similar to that described by O’Driscoll and colleagues.1 After diagnostic arthroscopy confirms the instability and the absence of associated pathology, an extensile posterolateral approach is used, and the anconeus muscle is split or retracted anteriorly to access the RUHL complex. The ligaments are plicated and then repaired back to the humerus, as described for arthroscopic repair, if tissue is adequate to allow repair.

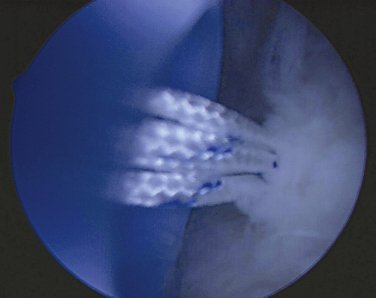

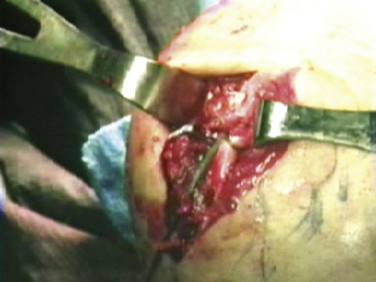

In patients undergoing revision surgery or in patients with inadequate tissue for repair, a palmaris longus or gracilis autograft may be used to reconstruct the joint. The supinator crest of the ulna just posterior to the radial neck is dissected free, and the insertion site is identified. A 4- to 6-mm tunnel is created in this spot. A Beath pin is drilled from this point out the ulnar side of the ulna and used to pull a passing suture out this side of the arm. The midportion of the graft is then pulled into the ulna and fixed using an interference screw technique. The two free graft limbs are then brought superiorly, pulling one under the annular ligament and one over the ligament, and they are attached to the isometric point on the posterior aspect of the lateral epicondyle. The graft should be slightly lax in extension and tighten with flexion (Fig. 12-11).

OUTCOMES

Savoie and associates published some of their data regarding the results of surgery for injuries to the lateral ligaments.10 The results of the arthroscopic procedures were equal to those of open repair or grafting in their series. In the series, 54 patients had a PLRI repair, plication, or graft performed. Forty-one patients (20 arthroscopic, 21 open) had a combined plication and repair, 10 patients (6 open, 4 arthroscopic) had acute or subacute repairs for recurrent elbow instability, and 3 patients (all open) were reconstructed with a free tendon graft. Ten of the 20 arthroscopically treated and 11 of the 21 open plication or repair patients had the addition of an anchor to supplement the arthroscopic suture plication.

The average follow-up was 41 months (range, 12 to 103 months). Overall Andrews-Carson scores for all repairs improved from 145 to 180 (P < .0001).7 Subjective scores improved from 57 to 85 (P < .0001), and objective scores improved from 88 to 95 (P = .008). Subdividing the technique yielded these overall results: arthroscopic repairs improved from 146 to 176 (P = .0001), and open repairs improved from 144 to 182 (P < .001). Acute repairs seemed to perform the best, with 9 of 10 patients returning to normal activities and 1 patient returning to near-normal activities. There was no statistical difference between the results of open and arthroscopic repairs.

CONCLUSIONS

The diagnosis of PLRI is made by a combination of positive clinical findings and radiologic confirmation, and it may be supplemented by arthroscopic confirmation of instability, including varus opening, the arthroscopic drive-through sign of the elbow, and abnormal movement of the radial head and proximal radioulnar joint on the humerus. The posterolateral pivot shift test described by O’Driscoll and colleagues1 may be performed with the patient supine or prone, and combined with the internal rotation push-up and chair lift tests of Regan and Lapner,6 it provides a clear clinical picture of instability.

1. O’Driscoll SW, Bell DF, Morrey BF. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:440-446.

2. Dunning CE, Zarzour ZD, Patterson SD, et al. Ligamentous stabilizers against posterolateral rotator instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83A:1823-1828.

3. Seki A, Olsen BS, Jensen SL, et al. Functional anatomy of the lateral collateral ligament complex of the elbow: configuration of Y and its role. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:53-59.

4. Kalainov DM, Cohen MS. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow in association with lateral epicondylitis. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1120-1125.

5. Smith JP, Savoie FH, Field LD. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:47-58.

6. Regan W, Lapner PC. Prospective evaluation of two diagnostic apprehension signs for posterolateral instability of the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:344-346.

7. Andrews JR, Carson WG. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:97-107.

8. Yadao MA, Savoie FH, Field LD. Posterolateral rotator instability of the elbow. Inst Course Lect. 2004;53:607-614.

9. Potter HG, Weiland AJ, Schatz JA, et al. Posterolateral rotator instability of the elbow: usefulness of MR imaging in diagnosis. Radiology. 1997;204:185-189.

10. Savoie FH, Field LD, Gurley DJ. Arthroscopic and open radial ulnohumeral ligament reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Hand Clin. 2009;25:323-329.