Chapter 34 Arthropod bites and stings

Dahl MV: Cutaneous reactions to arthropod bites and stings, Clin Cases Dermatol 3:11–16, 1991.

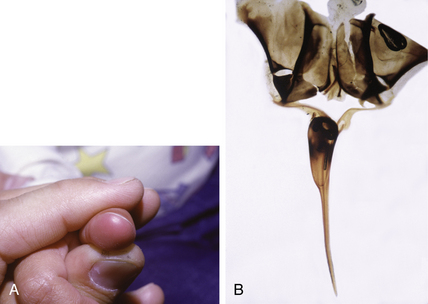

The venom-containing barbed stinger, if still present at the site of the sting, should be removed by gently scraping the skin horizontally with a dull knife or credit card (Fig. 34-1). Stinger removal with forceps compresses the venom gland, forcing more venom into the skin, and should be avoided. Symptomatic care with rest, elevation, and ice to the area are helpful. Antihistamines may also be useful. Early signs of systemic toxicity or allergic reactions should be noted.

Figure 34-2. Female black widow spider demonstrating the characteristic hour glass on the ventral surface. (iStock_6222259)

Elston DM: What’s eating you? Latrodectus mactans (the black widow spider), Cutis 69:257–258, 2002.

Key Points: Dermonecrotic Arachnidism

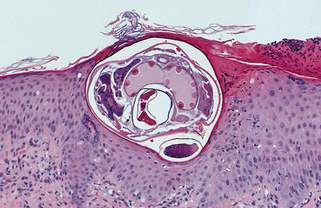

Figure 34-4. Biopsy of scabies demonstrating mite in burrow.

(Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD.)

Tran L, Siedenberg E, Corbett S: Crusted (Norwegian) scabies, J Emerg Med 22:285–287, 2002.

Karthikeyan K: Treatment of scabies: newer perspectives, Postgrad Med J 81:7–11, 2005.

Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini R Petal: Dermatology, Spain, 2008, Mosby-Elsevier.

Elston DM: Drugs used in the treatment of pediculosis, J Drugs Dermatol 4:207–211, 2005.

Steen CJ, Carbonaro PA, Schwarz RA: Arthropods in dermatology, J Am Acad Dermatol 50:819–842, 2004.

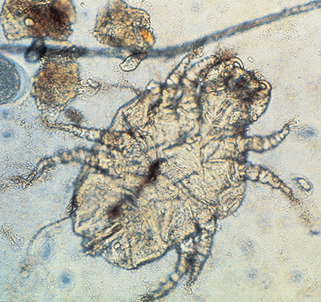

Figure 34-7. Cheyletiella mite resembles scabies in size but is identified by the hooklike palps anteriorly.

Other animals with mite infestations that affect humans include the following:

The pruritic bites are often multiple and grouped into a “breakfast, lunch, and dinner” pattern (Fig. 34-8B). Treatment of the patient is symptomatic, but fumigation of the home is necessary to get rid of the pest. With a good description of the bug, patients are often able to recover one to confirm the diagnosis.

Thomas I, Kihiczak GG, Schwartz RA: Bedbug bites: a review, Int J Dermatol 43:430–433, 2004.

Kolb A, Needham GR, Neyman KM, et al: Bedbugs dermatologic therapy 22:347–352, 2009.

In addition to constitutional symptoms of general malaise, aches and pains, and fever, the disease may be complicated by cardiac, neurologic, and arthritic symptoms. Treatment in the early phase consists of antibiotics such as amoxicillin, erythromycin, or, most likely, doxycycline for a 3-week period of time. If Lyme disease progresses on to a more chronic problem, or there is evidence of neurologic symptoms, it is often necessary to use ceftriaxone in order to cross the blood–brain barrier.

Figure 34-10. Attached feeding tick with an allergic host response manifesting as erythema and induration.

(Courtesy of the Fitzsimons Army Medical Center teaching files.)

Gammons M, Salam G: Tick removal, Am Fam Physician 15:643–645, 2002.

| INFECTIOUS DISEASE | VECTOR |

|---|---|

| Anaplasmosis (human granulocytotropic) | Hard ticks |

| Arboviruses (including yellow fever, dengue, encephalitis) | Mosquitos, ticks |

| Babesiosis | Hard ticks |

| Boutonneuse fever (tick-bite fever) (Rickettsia conorii) | Rabbit flea |

| Chagas disease | Triatomid (kissing) bugs |

| Colorado tick fever | Hard ticks |

| Ehrlichiosis, monocytotropic (Ehrlichia ewingii) | Hard ticks |

| Endemic relapsing fever (Borrelia duttoni) | Soft ticks |

| Epidemic relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis) | Human body lice |

| Epidemic typhus (R. prowazekii) | Human body lice |

| Filariasis (Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi) | Mosquitos |

| Leishmaniasis (Leishmania spp.) | Phlebotomid flies |

| Loiasis (Loa loa) | Tabanid flies |

| Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) | Hard ticks |

| Malaria (Plasmodium spp.) | Mosquitos |

| Murine typhus (R. mooseri) | Rat fleas, lice |

| Onchocerciasis (Onchocerca volvulus) | Black flies |

| Plague (Yersinia pestis) | Rat fleas |

| Q fever (Coxiella burnetii) | Hard ticks, fleas |

| Rickettsial pox (R. akari) | Mouse mites |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever (R. rickettsii) | Hard ticks |

| Scrub typhus (R. tsutsugamushi) | Mites (chiggers) |

| Trypanosomiasis, African sleeping sickness | Glossina (tsetse) flies |

| West Nile fever | Mosquitos |

Adapted from Braunstein, WB: Ectoparasites. In Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors: Principles and practice of infectious diseases, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2005, Elsevier, pp 3301–3302.

Elston DM: Insect repellents: an overview, J Am Acad Dermatol 38:644–645, 1998.