CHAPTER 26 Arthrofibrosis

Some degree of shoulder stiffness is very common in clinical practice. Stiffness may or may not be the primary complaint of the patient. Weakness, pain, or even (paradoxically) a feeling of instability may have brought the patient to see the physician. Stiffness can be the primary problem, as in the case of chronic adhesive capsulitis, or may be secondary to other conditions such as trauma, rotator cuff disease, or arthritis. In our evaluation of patients with rotator cuff tears, 30 of 72 had a motion deficit of 20 degrees or more.1 It is particularly important to use the term idiopathic adhesive capsulitis only for that specific pathologic condition and not as a description of shoulder stiffness in general. Stiffness of the shoulder may be truly mechanical and attributable to a specific anatomic abnormality, or can be nonanatomic and caused by guarding because of pain or secondary gain issues. In this chapter, we will outline the various anatomic causes of shoulder stiffness and provide a guide for clinical diagnosis and treatment.

ANATOMY, PATHOANATOMY, AND ETIOLOGY

Adhesive Capsulitis

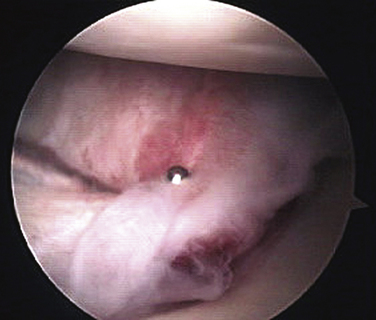

Adhesive capsulitis can be idiopathic, related to diabetes, or associated with other pathology about the shoulder. There is no standard agreement as to what range-of-motion (ROM) loss constitutes adhesive capsulitis.2 The classic, severely inflamed, thickened, and contracted capsule is pathgnomonic (Fig. 26-1). Fibroblast proliferation and smooth muscle phenotypic transformation has been found in the capsular tissue of some patients with adhesive capsulitis, similar to Dupuytren’s contracture in the hand.3 Diabetes is commonly associated with adhesive capsulitis.1,4,5 Any pathologic condition that causes primary or referred pain to the shoulder can potentially initiate an inflammatory cascade leading to adhesive capsulitis. Whereas adhesive capsulitis occurs in patients with rotator cuff disease, no relationship to acromial morphology has been found.6 Harryman has compiled an extensive list of possible pathogenic mechanisms but little scientific evidence exists to support any particular entity.7

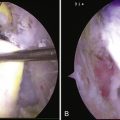

Milder Secondary Mechanical and/or Capsular Contractures

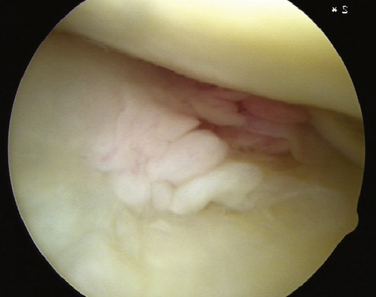

Some patients exhibit lesser degrees of shoulder stiffness compared with adhesive capsulitis. The capsule in these cases will typically have inflammatory changes or the synovium may be inflamed, but to a much lesser extent than in adhesive capsulitis (Fig. 26-2). Many patients with rotator cuff tears have mild stiffness before surgery. Patients with mild or moderate stiffness before surgery tend to have persistent stiffness after surgery but the prognosis for ultimate recovery of almost full motion is very good. Only those patients who have frank adhesive capsulitis at the time of surgery are unlikely to recover satisfactory ROM after surgery.1,8

Focal Capsular Contracture

Throwing athletes and other patients exposed to chronic repetitive throwing injuries are known to develop focal capsular contractures. Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) is a contracture of the posterior inferior shoulder capsule resulting in a loss of internal rotation in the abducted shoulder. GIRD is often associated with SLAP (superior labrum anteroposterior) lesions and partial rotator cuff tears.9

Acute Trauma

Shoulder stiffness following trauma can be caused by soft tissue scarring or fracture malalignment. Patients older than 40 years who suffer a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation are more prone to the development of stiffness, including adhesive capsulitis, than younger patients.10 For patients with a displaced proximal humerus fracture, there is wide variation in the incidence of stiffness in the published literature, with some studies reporting overall 50% ROM loss for all forms of treatment, including nonoperative, open reduction internal fixation, and hemiarthroplasty.11 Reports of hemiarthroplasty for three- and four-part proximal humeral fractures differ, with some favorable12 and others showing disappointing results.13 A review of older patients with three-part fractures of the proximal humerous treated nonoperatively reported that only 4 of 15 patients had residual pain. However, these patients had significant residual stiffness, with mean flexion and abduction less than 100 degrees.14 Even isolated greater tuberosity fractures of the shoulder have been shown to cause residual pain and stiffness if displaced 3 mm or more. ROM is typically better with surgical intervention.15,16 Recently, success has been reported in the arthroscopic reduction and treatment of greater tuberosity fractures.17,18

Postsurgical Stiffness

Hematoma and secondary fibrosis or overtightening of the shoulder capsule or repaired rotator cuff structures may result in a restriction of motion. Incomplete reduction of fracture fragments after surgical repair can cause mechanical blocks to motion. One review of open rotator cuff repairs has reported a 4% incidence of significant postoperative adhesions. Although arthroscopic or open release was found to be effective, closed manipulation was not.19 Diabetic patients may be more prone to stiffness after rotator cuff repair.20 Long- term follow-up of patients who have undergone open instability repairs has shown a high incidence of osteoarthritis (40% to 60%). At least 30% of these patients have significant loss of motion.21–23 For shoulder replacement surgery, the most common reported cause of failure is stiffness.24 Arthroscopic Bankart repair is associated with very small ROM deficits, generally less than 5 degrees.25,26 However, rotator interval closure has been shown to reduce flexion, external rotation, and anterior translation of the adducted shoulder significantly.27 Thermal capsular shrinkage for multidirectional instability may also cause significant stiffness in some patients.28 Open surgical procedures in proximity to the shoulder can also cause loss of motion, including breast surgery29 and cardiac surgery.30

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF THE STIFF SHOULDER

Physical Examination

The examination should include an evaluation of posture, muscular atrophy, areas of tenderness, active and passive ROM limits, and strength. Tests for subacromial impingement and scapular dyskinesia are performed. The cervical spine is examined for tenderness, loss of motion, and trigger points. An assessment of the neurovascular status of the upper extremities is made. The examiner should avoid painful tests or placing the shoulder in painful positions until the end of the examination to minimize guarding during ROM evaluation. The physical examination checklist is summarized in Box 26-1.

Box 26-1 Physical Examination Checklist

RANGE OF MOTION

The direction of ROM loss and the position of the shoulder point to the location of the contracted tissues. For example, patients with GIRD will primarily display loss of internal rotation with the arm abducted, but usually not with the arm adducted.31,32 Injection of 1% lidocaine into specific regions can help determine the pathoanatomy that is generating the pain and also helps reduce guarding so that the true ROM deficit can be determined. If subacromial injection results in pain relief and improved mobility, the likely cause of the patient’s problem is rotator cuff tendinitis and appropriate treatment is instituted. If pain and stiffness persist despite subacromial injection, an intra-articular injection is given. If pain is relieved but stiffness persists, the patient most likely has adhesive capsulitis. Box 26-2 summarizes the typical history and physical findings by diagnosis.

TREATMENT

Indications and Contraindications

In general, patients with chronic stiffness should have conservative treatment first. Any decision for surgery needs to be made based not only on the diagnosis, but on the patient’s age, medical condition, and premorbid activity level. Surgical indications and contraindications are summarized in Box 26-3. Each surgical indication assumes a failure of conservative treatment.

In patients with rotator cuff tears, some degree of stiffness is common. ROM loss is measured in flexion, abduction, and internal and external rotation. Those ROM deficiencies are added together to determine the total ROM deficit (TROMD). Patients with less than 75 degrees of TROMD are unlikely to have concomitant adhesive capsulitis and will gradually recover their ROM after cuff repair with routine physical therapy. Patients with more than 75 degrees of TROMD have a 50% incidence of concomitant adhesive capsulitis and may not recover sufficient ROM after repair. These patients require treatment for adhesive capsulitis prior to repair. If they have been in the chronic phase for at least 3 months, a release followed by a rotator cuff repair as a second procedure is typically performed, although simultaneous capsular release and rotator cuff repair may yield good results in selected cases.1

Prevention is superior to late treatment. For soft tissue trauma, including dislocations, early mobilization is indicated in older patients because they are more prone to become stiff but are unlikely to have recurrent instability. For associated greater tuberosity fractures, no more than 3 mm of displacement should be accepted in active patients, and no more than 5 mm in lower demand patients.33 For fractures treated closed, mobilize the joint as soon as pain and initial healing will permit. If the fracture is treated surgically, fixation that can withstand early ROM will help reduce postoperative stiffness. For hemiarthroplasty, secure and anatomic tuberosity and cuff fixation will allow earlier motion.

Conservative Treatment

Adhesive Capsulitis

In the acute phase, adhesive capsulitis is characterized by marked stiffness and pain at rest. The goal of initial treatment is to control pain, decrease inflammation, and convert the disease to the chronic phase, characterized by marked stiffness but no rest pain. Vigorous attempts at stretching should be avoided in the acute phase as these are is ineffective and painful. Both oral and intra-articular steroids have been shown to improve early comfort, but have not changed long-term outcomes.34,35 Narcotic pain medications may be necessary initially in combination with and as a transition to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as the pain level subsides. Once the patient is in the chronic phase, a protocol of active assistive range of motion (AAROM) and passive range-of-motion (PROM) exercises, initially supervised by a physical therapist, is used. Some of the AAROM exercises that may be warranted include pulley exercises, pendulums, towel stretches, and table slides to improve mobility. These exercises are usually done in a physical therapy clinic three to five times weekly, with transition to a home stretching program performed three to five times daily. These exercises are done to the patient’s tolerance, avoiding additional pain and trauma to the shoulder joint. Several studies have shown approximately 90% patient satisfaction with the use of analgesics and a supervised or home therapy program, but significant residual loss of motion may persist, up to 30 degrees in each plane.36,37

Rotator Cuff Tear–Related Stiffness

Stiffnes related to cuff tears that is moderate will usually recover with routine physical therapy modalities for stretching and with time, sometimes up to 2 years after rotator cuff repair. Patients with more severe ROM loss may have capsulitis in addition to their tear and are best treated for the capsulitis before any repair is undertaken. This group of patients may present initially with typical impingement pain but become acutely much more painful as capsulitis develops. Diabetic patients with rotator cuff tears are more likely to have capsulitis than nondiabetic patients.1,20 Once these patients are in the chronic phase, options include nonoperative treatment of the capsulitis and cuff tear if symptoms resolve over time, nonoperative care of the adhesive capsulitis until stiffness resolves, and then rotator cuff repair if cuff symptoms persist, or staged arthrosopic capsular release followed by rotator cuff repair as a second procedure once mobility returns. Simultaneous capsular release and rotator cuff repair should be reserved for patients with only mild restriction of motion in this challenging diabetic population, or for non-diabetic patients with moderate ROM loss.

Post-traumatic and Postsurgical Stiffness

Stiffness related to trauma and surgery is usually treated initially with physical therapy, emphasizing gentle stretching and pain modalities. Overly aggressive therapy should be avoided because it can exacerbate pain and stiffness, as it would in the acute phase of adhesive capsulitis. Pain management is very important. Appropriate analgesics should be prescribed and physical therapy should concentrate on modalities to relieve pain. A pain management subspecialist should be consulted in resistant cases. If there is evidence of reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), the patient’s response to a cervical sympathetic nerve block should be ascertained.

Operative Treatment

Adhesive Capsulitis

In one study of manipulation under anesthesia versus arthroscopic capsular release, the patients in the arthroscopic release group had better pain relief and restoration of function.38 Associated pathology is common in adhesive capsulitis and a thorough arthroscopic evaluation of the joint should be completed. Arthroscopic compared with open release is significantly less morbid and has been shown to be approximately 90% effective in improving ROM in nondiabetic and diabetic patients.5,38,39 In our practice, we wait for the patient to be in the chronic phase, with no rest pain for at least 2 months before considering surgery. Compared with conservative treatment, arthroscopic release offers a quicker recovery, with somewhat greater eventual motion gains.

Arthroscopic Capsular Release for Adhesive Capsulitis: Detailed Technique

Initial Arthroscopic Evaluation.

A hemarthrosis will usually need to be irrigated out to allow for visualization. Then, establish a standard anterior superior working portal in the rotator interval. A thick, erythematous and contracted capsule is pathopneumonic. Evaluate the glenohumeral joint for other associated pathology, ie, a rotator cuff tear. Perform necessary releases based on the recommendations in Table 26-1.

| ROM Deficit | What to Release |

|---|---|

| Abduction | Inferior capsule, axillary recess |

| Forward flexion | Inferior capsule, anterior capsule |

| ER in adduction | Anterior capsule, rotator interval |

| ER in abduction | Anterior capsule, inferior capsule |

| IR in adduction | Posterior-superior capsule |

| IR in abduction | Posterior-inferior capsule |

ER, external rotation; IR, internal rotation.

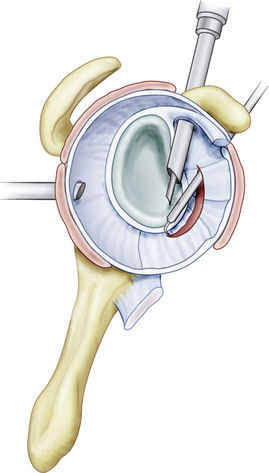

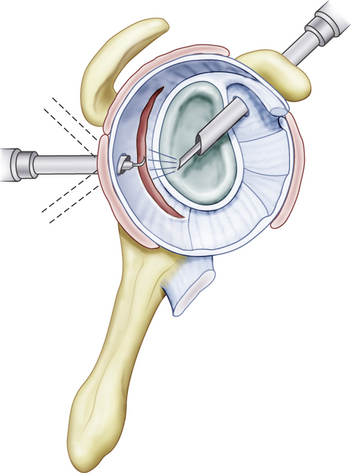

Anterior Capsular Release.

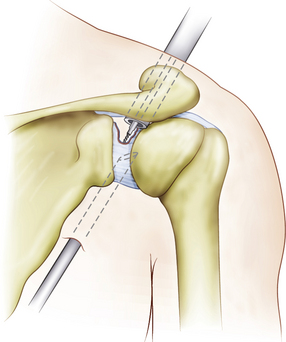

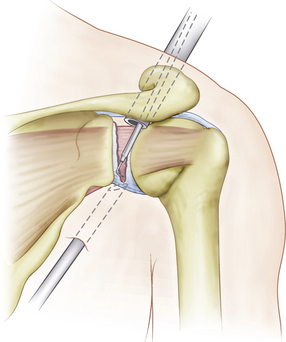

The anterior release is performed first. While viewing from the posterior portal, use a 90-degree hooked radiofrequency (RF) electrode in the anterior portal for cutting the capsule. Release the middle glenohumeral ligament (MGHL) area first, followed by the anterior inferior glenohumeral ligament (AIGHL; Figs. 26-3 to 26-5). The capsule should be cut until the subscapularis muscle belly is exposed. Do not cut the muscle.

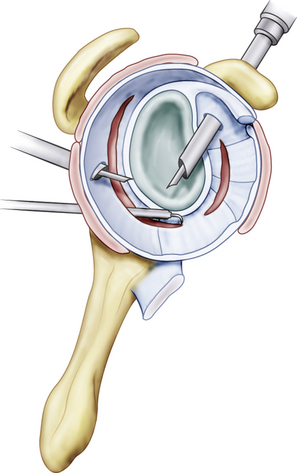

Posterior Capsular Release.

To release the posterior-inferior capsule, direct the electrode inferiorly and cut the capsule from the posterior portal to the posterior-inferior corner of the glenoid, just posterior to the labrum. Cut the capsule until the teres minor muscle belly is exposed (Figs. 26-6 and 26-7).

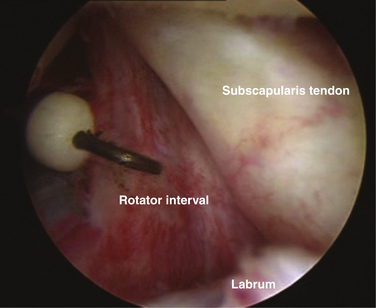

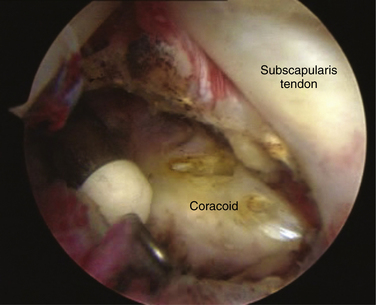

Rotator Interval Release

With the arthroscope in the posterior portal, insert the cutting electrode through the anterior superior portal. Cut the rotator interval capsule from the superior border of the subscapularis tendon to biceps 1 to 1.5 cm anterior to the glenoid rim. Continue cutting to expose the tip of the coracoid, exposing the attached coracoacromial ligament superiolaterally and the conjoined tendon inferiorly (Figs. 26-8 and 26-9).

Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit

If rehabilitation fails, MR arthrography is indicated to identify associated SLAP and cuff lesions, which should be treated at the time of a posterior-inferior capsular release.9,31,32

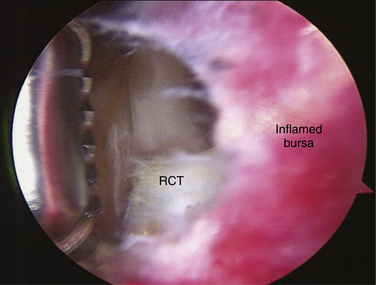

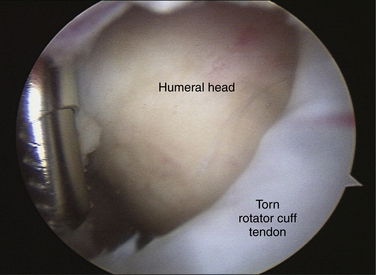

Rotator Cuff Tear–Related Stiffness

Significant stiffness may be intracapsular and extracapsular. If rehabilitation fails, capsular and subacromial releases must be performed.14 A gentle MUA followed by a postmanipulation ROM-specific capsular release is performed first (see earlier). The arthroscope is then placed into the subacromial space and scarred bursal tissue is removed. Figures 26-10 and 26-11 show the results of bursal débridement in a patient undergoing a simultaneous rotator cuff repair and capsular release. The rotator cuff tear cannot be adequately visualized and repaired until débridement is complete. The cuff tendon may also need to be mobilized with an anterior interval release or, rarely, a posterior interval release between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. Cuff repair after capsular release can be challenging because of bursal edema and bleeding and can be done as a second-phase procedure at a later date, if necessary.

Post-Traumatic or Postsurgical Stiffness

If there is no progress in rehabilitation after at least 4 months in acute cases or 2 months in chronic cases, surgical release can be considered. The specific surgical approach depends on which structures are scarred or contracted. Overaggressive capsular tightening after arthroscopic instability surgery often involves the rotator interval. An appropriate arthroscopic interval capsular release would be indicated (see Figs. 26-8 and 26-9). Post-traumatic and postoperative secondary adhesive capsulitis can occur in some patients. This should be treated in a manner similar to that for primary adhesive capsulitis case (see earlier).

Most studies of arthroscopic release have found no significant difference among idiopathic, postoperative, post-traumatic, and diabetic groups.33,34 Some have found idiopathic groups to do better35 but results have been generally satisfactory in all groups. In our experience, capsular and limited extracapsular adhesions can be treated well with an arthroscopic release, whereas extensive postoperative or post-traumatic extracapsular adhesions or muscle contractures are best treated with a combined arthroscopic and limited open approach. Figure 26-12 illustrates the use of the standard lateral subacromial portal for the finger dissection technique in cases of more diffuse subdeltoid adhesions. This is typically performed after gentle manipulation under anesthesia and arthroscopic capsular release.

Degenerative Arthritis

Arthroscopic débridement and capsular release have been reported to improve ROM in 10 of 12 patients with marked stiffness and osteoarthritis.36 Patients with rheumatoid arthritis who do not have advanced destructive disease may benefit from arthroscopic synovectomy.37

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

PITFALLS

ANESTHESIA AND PAIN MANAGEMENT FOR THE ARTHROFIBROSIS PATIENT

Anesthetic techniques for shoulder surgery can vary from general anesthesia, with or without regional anesthesia, to a regional anesthetic with intravenous sedation. Regional anesthesia is a desirable adjunct for the arthrofibrosis patient because pain relief is superior and can be prolonged with continuous infusion techniques. An interscalene block can last up to 12 hours or longer, depending on the anesthetic and its concentration and volume. Continuous interscalene catheters may provide analgesia for 2 or 3 days or longer, depending on the volume of the reservoir and the flow rate of the infusion used. Improved analgesia using these continuous methods reduces the use of opioid analgesics and their potential side effects and facilitates early, more aggressive physical therapy.38 The use of ultrasound guidance can help reduce the risk of intravascular injection, improve the success of brachial plexus blockade, and reduce the volume of anesthetic needed.39

SUMMARY

Appropriate treatment of shoulder stiffness is dependent on an accurate diagnosis and understanding of the specific pathoanatomy and corresponding treatment associated with that condition. In all categories of shoulder stiffness, coordination with skilled and experienced rehabilitation and pain management specialists is essential. For primary or secondary adhesive capsulitis, nonoperative treatment is always indicated until the patient is in the chronic phase, characterized by persistent stiffness but no rest pain. Arthroscopic release is an option that has been shown to be effective for appropriate patients. Mild and moderate stiffness in patients with rotator cuff tears will resolve with repair, rehabilitation, and time. Patients with more severe stiffness (combined ROM deficit more than 70 degrees) may have associated capsulitis and should be treated for that diagnosis initially. For acute and chronic trauma, as well as for postsurgical stiffness, preventive strategies are the most important and effective. Rehabilitation is initially indicated for most of these patients. For patients who have failed nonoperative treatment, successful surgical correction is dependent on an understanding of the specific anatomic structures involved so that appropriate soft tissue releases can be performed. A summary treatment guide for shoulder stiffness by diagnosis is shown in Box 26-4.

Box 26-4 Summary of Treatment by Diagnosis

1. Tauro JC Stiffness and rotator cuff tears: incidence, arthroscopic findings, and treatment results. Arthroscopy, 22; 2006:581-586.

2. Harryman DT, Lazarus MD, Rosencwaig R. The stiff shoulder. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, editors. The Shoulder. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998:1064-1112.

3. Bunker TD, Anthony PP. The pathology of frozen shoulder. A Dupuytren-like disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:677-683.

4. Boyle-Walker KL, Gabard DL, Bietsch E, et al. A profile of patients with adhesive capsulitis. J Hand Ther. 1997;10:222-228.

5. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Myerthall S The diabetic frozen shoulder: arthroscopic release. Arthroscopy, 13; 1997:1-8.

6. Richards DP, Glogau AI, Schwartz M, Harn J. Relation between adhesive capsulitis and acromial morphology. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:614-619.

7. Harryman DT Shoulders: frozen and stiff. Instr Course Lect, 42; 1993:247-257.

8. Trenerry K, Walton JR, Murrell GA. Prevention of shoulder stiffness after rotator cuff repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;430:94-99.

9. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology. Part IIevaluation and treatment of SLAP lesions in throwers. Arthroscopy, 19; 2003:531-539.

10. Pevny T, Hunter RE, Freeman JR. Primary traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation in patients 40 years of age and older. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:289-294.

11. Zyto K, Kronberg M, Brostrom LA. Shoulder function after displaced fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4:331-336.

12. Mighell MA, Kolm GP, Collinge CA, Frankle MA. Outcomes of hemiarthroplasty for fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:569-577.

13. Zyto K, Wallace WA, Frostick SP, et al. Outcome after hemiarthroplasty for three-and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:85-89.

14. Zyto K. Non-operative treatment of comminuted fractures of the proximal humerus in elderly patients. Injury. 1998;29:349-352.

15. George MS. Fractures of the greater tuberosity of the humerus. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:607-613.

16. Platzer P, Thalhammer G, Oberleitner G, et al displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity: a comparison of operative and nonoperative treatment. J Trauma, 65; 2008:843-848.

17. Ji JH, Kim WY, Ra KH. Arthroscopic double-row suture anchor fixation of minimally displaced greater tuberosity fractures. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1133.

18. Song HS, Williams GRJr. Arthroscopic reduction and fixation with suture bridge technique for displaced or comminuted greater tuberosity fractures. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:956-960.

19. Warner JJ, Greis PE. The treatment of stiffness of the shoulder after repair of the rotator cuff. Instr Course Lect. 1998;47:67-75.

20. Chen AL, Shapiro JA, Ahn AK, et al. Rotator cuff repair in patients with type I diabetes mellitus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:416-421.

21. van der Zwaag HM, Brand R, Obermann WR, Rozing PM. Glenohumeral osteo-arthrosis after Putti-Platt repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:252-258.

22. Allain J, Goutallier D, Glorion C. Long-term results of the Latarjet procedure for the treatment of anterior instability of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:841-852.

23. Pelet S, Jolles BM, Farron A Bankart repair for recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability: results at twenty-nine years’ follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 15; 2006:203-207.

24. Hasan SS, Leith JM, Campbell B, et al. Characteristics of unsatisfactory shoulder arthroplasties. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:431-441.

25. Kim SH, Ha KI, Cho YB, et al Arthroscopic anterior stabilization of the shoulder: two to six-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 85; 2003:1511-1518.

26. Tauro JC Arthroscopic inferior capsular split and advancement for anterior and inferior shoulder instability: technique and results at 2-to 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy, 16; 2000:451-456.

27. Plausinis D, Bravman JT, Heywood C, et al Arthroscopic rotator interval closure: effect of sutures on glenohumeral motion and anterior-posterior translation. Am J Sports Med, 34; 2006:1656-1661.

28. Miniaci A, McBirnie J. Thermal capsular shrinkage for treatment of multidirectional of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:2283-2287.

29. Bosompra K, Ashikaga T, O’Brien PJ, et al Swelling, numbness, pain, and their relationship to arm function among breast cancer survivors: a disablement process model perspective. Breast J, 8; 2002:338-348.

30. Tuten HR, Young DC, Douoguih WA, et al. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder in male cardiac surgery patients. Orthopedics. 2000;23:693-696.

31. Yoneda M, Nakagawa S, Mizuno N, et al. Arthroscopic capsular release for painful throwing shoulder with posterior capsular tightness. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:801-805.

32. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology Part Ipathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy, 19; 2003:404-420.

33. Gerber C, Espinosa N, Perren TG. Arthroscopic treatment of shoulder stiffness. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;390:119-128.

34. Nicholson GP Arthroscopic capsular release for stiff shoulders: effect of etiology on outcomes. Arthroscopy, 19; 2003:40-49.

35. Holloway GB, Schenk T, Williams GR, et al. Arthroscopic capsular release for the treatment of refractory postoperative or post-fracture shoulder stiffness. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1682-1687.

36. Weinstein DM, Bucchieri JS, Pollock RG, et al. Arthroscopic débridement of the shoulder for osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:471-476.

37. Smith AM, Sperling JW, O’Driscoll DW, Cofield RH. Athroscopic shoulder synovectomy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:50-56.

38. Fredrickson MJ, Ball CM, Dalgleish AJ. Successful continuous interscalene analgesia for ambulatory shoulder surgery in a private practice setting. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:122-128.

39. Swenson JD, Bay N, Loose E Outpatient management of continuous peripheral nerve catheters placed using ultrasound guidance: an experience in 620 patients. Anesth Analg, 103; 2006:1436-1443.