CHAPTER 70 Arthrodesis

INTRODUCTION

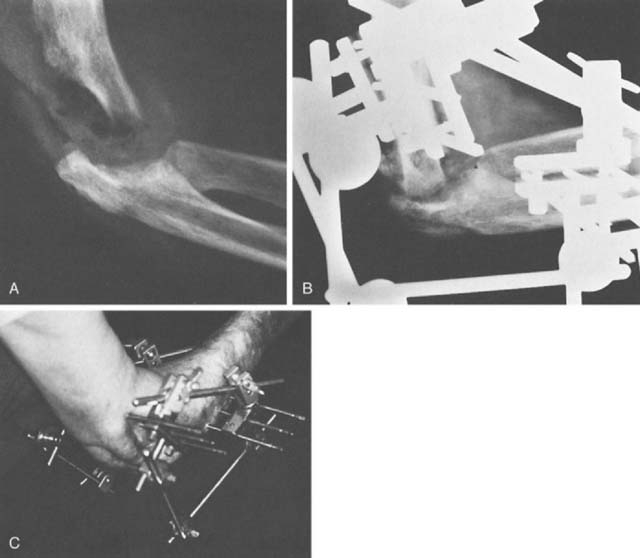

Experience with elbow arthrodesis is often related to injuries seen from military conflict.2 Most civilian experience with elbow fusion has come from spontaneous arthrodesis subsequent to infection, trauma, or rheumatic disease of the elbow (Fig. 70-1). One of the prerequisites for elbow fusion is satisfactory function of the shoulder; yet, studies from our laboratory have clearly shown that the increased shoulder motion cannot compensate for loss of elbow motion (Fig. 70-2).17

FIGURE 70-1 Spontaneous arthrodesis (A) is more common than surgically performed fusion (B) in a civilian population.

Biomechanical and clinical studies have demonstrated that compensatory spinal column and wrist motions are used to improve function after elbow arthrodesis.17 Thus, limited function (motion) in these areas may be a relative contraindication to elbow arthrodesis. When disease involves both the elbow and the shoulder, arthroplasty must, therefore, be selected. In addition, arthrodesis is not indicated for bilateral elbow disease because the functional limitations are too great. If bilateral arthrodesis is performed, one elbow should be fused in 90 degrees of flexion for personal care and hygiene functions and the other in 45 to 65 degrees of flexion for other uses.9,17 Functionally, a limited range of 100 degrees in midposition is enough for most daily activities, but removing all elbow motion restricts the majority of necessary daily functions.14 Hence, some patients request fusion take-down and total elbow even after many years (see Chapter 58).

POSITION

The optimal position for fusion depends on associated joint involvement, gender, the patient’s occupation, or specific functional requirements. Traditionally, 110 degrees is a more functional position.26 For men, 90 degrees of flexion is probably the best position of arthrodesis in a dominant arm that has good shoulder and wrist motion.16 In this position, the hand can reach the mouth with adaptive neck, shoulder, and wrist motion, and writing may be done comfortably. This has recently been challenged by one recent study suggesting special needs for the nondominant arm may prompt fusion in 30 degrees or 60 degrees of flexion, if, for example, bench work or assistive movements are required.17,22 If power is not an issue, a position of 70 degrees may be desirable.

INDICATIONS

Because of the limitations mentioned earlier, arthrodesis of the elbow is not often indicated. In fact, although shoulder fusion was employed in 23 of 144 patients with brachial plexus injury, elbow fusion was not preferred in a single patient.21 If it has a place in the surgeon’s armamentarium, it is for younger patients with post-traumatic unilateral arthrosis of the elbow who require a strong and stable joint.2 In patients older than 45 years who have bilateral disease and limited shoulder or wrist motion, arthroplasty, with or without joint replacement, is preferable. For unilateral postinfectious arthrosis, Rashkoff and Burkhalter proposed plate fixation of contaminated traumatic injuries of the elbow with chronic sepsis.13,20 Arthrodesis may be difficult to achieve after failed total elbow arthroplasty and is rarely indicated.11,27 It has yet to be performed at the Mayo Clinic after more than 1700 elbow replacements.

TECHNIQUE

Most of the limited reports on arthrodesis deal with the various techniques.1,3,11,15,18 The elbow is one of the most difficult joints to fuse surgically. The hand and the forearm act as a long lever arm that produces strong bending forces across the potential fusion site. Success rates have improved considerably with adjunctive internal fixation and intramedullary bone grafting.11

HISTORICAL SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

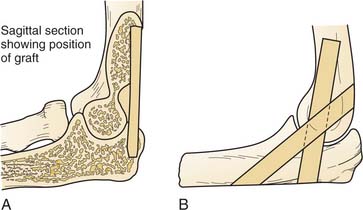

Steindler25 described a single posterior tibial cortical graft keyed into the olecranon for fusion (Fig. 70-3A). Brittain developed a technique of crossed grafts through the elbow joint5,7 (see Fig. 70-3B). Noting that gravitational forces tended to compress the ends of the graft, he believed that the crossing of the grafts was important. Koch and Lipscomb12 have described a modification of this technique in which a tibial graft is placed through a large drill hole in the humerus and ulna, and other cancellous bone grafts are added to the joint.

Staples24 uses a corticocancellous iliac graft through the posterior portion of the elbow and oblique hum-eral and olecranon intra-articular resection (see Fig. 70-3C).

STABILIZATION

Today, rigid fixation with supplemental autogenous or allograft bone is preferred. In the presence of active infection, external skeletal fixation has been preferred; however, fusion with plate stabilization, antibiotics, and an open wound can also succeed.13,20 In the presence of long-standing sepsis or arthrosis with limited motion and minimal deformity, arthrodesis may be achieved with limited internal fixation (screws), with or without bone grafts.11 If significant instability or deformity is present preoperatively, internal fixation with screws and supplemented with external skeletal fixation or plates should be used. Today, data clearly favor use of internal fixation.10 External fixation alone was successful in only five of nine in a recent series from Germany.

TECHNICAL OPTIONS

Plate Fixation

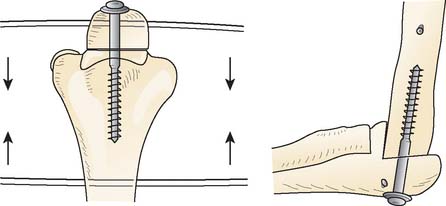

Spier23 and Plank19 have described a compression arthrodesis that makes use of a bent plate and an external compression device (Fig. 70-4). This is also the method favored by Burkhalter13 and is probably most commonly used today.18

Compression Screws

For post-traumatic arthrosis of the elbow with minimal motion that causes significant pain, we have used compression fixation of the elbow with screws. The procedure involves partial débridement of remaining articular surfaces and compression screw fixation without grafts (Fig. 70-5). Others have subsequently reported on similar techniques.11,18

For active draining sinuses due to tuberculosis, Arafiles1 has described a technique that locks the olecranon in the humeral fossa and stabilizes it by screw fixation.

EXTERNAL SKELETAL FIXATION

Bonnel3 reported a successful case of elbow arthrodesis (for failed arthroplasty) in which external skeletal fixation was combined with bone grafting (Fig. 70-6). In the presence of active sepsis, synovectomy and débridement of the radial head and articular surfaces, followed by external skeletal fixation allows spontaneous arthrodesis to occur in the desired position. Fixation has also been described with a bilateral trapezoidal frame.

FIGURE 70-6 Fixation of humerus, radius, and ulna with Hoffmann’s device for arthrodesis of elbow.

(From Bonnel, F.: Technique d’arthrodese du coude par fixateur externe. J Chir. [Paris] 107:79, 1974.)

Two transfixing pins are placed in the midportion of the humerus and in the proximal ulna. Care must be taken to avoid the radial and ulnar nerves. Three nontransfixing pins are placed in the midportions of the radius and ulna, and the trapezoidal configuration is completed.6 There is, however, no single arrangement that must be followed; rather, the design is dictated by the lesion, especially by the amount of bone fusion (Fig. 70-7).

Combination: AO Compression

When possible, axial compression with external fixation coupled with a cancellous lag screw placed into the humeral shaft is an attractive blend of concepts (Fig. 70-8). Through a posterior approach, the surfaces of the distal humerus and olecranon are resected to provide a wedge fit. The radial head is excised, and a Kirschner wire is passed from the olecranon up the humeral shaft. Transverse pins are inserted through the olecranon and humerus, the Kirschner wire is removed, and a long, cancellous screw is inserted with a washer up the shaft of the humerus. External compression clamps are then applied.

AUTHOR’S PREFERRED METHOD OF TREATMENT

FOR UNSTABLE ELBOWS

With Infection

In the presence of infection and an unstable elbow, however, I prefer to use simple external skeletal fixation with cancellous grafting, if necessary. There is often a hypertrophic bony response to infection. Thus, external skeletal fixation with the bilateral or unilateral triangular configuration can achieve compression and good immobilization and allow the wounds to be left open and to close gradually in anticipation of spontaneous union (see Fig. 70-7).

COMPLICATIONS

Nonunion

Few data are available about success rates for primary arthrodesis. Koch and Lipscomb reported that primary arthrodesis failed in nine of 17 patients treated at the Mayo Clinic.12 Six of 11 elbows treated for tuberculosis failed to unite. Extensive joint destruction and unavailability of chemotherapy were cited as contributory factors to this poor rate of fusion. A recent updating of the Mayo Clinic experience has demonstrated a significant decrease in nonunion rates with internal fixation. Hahn documented six of six fusions with a combination of internal and external fixation but only five of nine fused when external fixation alone was used.10

Fracture

The long lever arm created by elbow fusion increases stress along the entire extremity. Fracture through or proximal to the fused or ankylosed joint is not uncommon and was reported in four of 17 patients by Koch and Lipscomb.12 Conservative treatment, however, usually results in union (Fig. 70-9).

1 Arafiles R.P. A new technique of fusion for tuberculous arthritis of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:1396.

2 Bilic R., Kolundzic R., Bicanic G., Korzinek K. Elbow arthrodesis after war injuries. Mil Med. 2005;170:164.

3 Bonnel F. Technique d’arthrodese du coude par fixateur externe. J. Chir. (Paris). 1974;107:79.

4 Boyd A.D.Jr, Thornhill T.S. Surgical treatment of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. Hand Clin. 1989;5:645.

5 Brittain H.A. Architectural Principles in Arthrodesis, 2nd ed., Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone; 1952:161.

6 Connes H. Hoffmann’s External Anchorage: Techniques, Indications and Results. Paris: Editions GEAD, 1977;118.

7 Crenshaw A.H., editor. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 5th ed.. C. V. Mosby Co., St. Louis, 1971;1191.

8 Dahl H.K. AO Metoden ved Osteotomi og Arthrodese. Nord. Med. 1971;85:599.

9 Figgie M.P., Inglis A.E., Mow C.S., Wolfe S.W., Sculco T.P., Figgie H.E.III. Results of reconstruction for failed total elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. 1990;253:123.

10 Hahn M.P., Ostermann P.A., Richter D., Muhr G. Elbow arthrodesis and its alternative. Orhtopade. 1996;25:112.

11 Irvine G.B., Gregg P.J. A method of elbow arthrodesis: brief report. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71B:145.

12 Koch M., Lipscomb P.R. Arthrodesis of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. 1967;50:151.

13 McAuliffe J., Burkhalter W. Post-traumatic elbow infection and fixation failure. Orthop. Consultation. 1991;12:1.

14 Morrey B.F., Askew L.J., An K.N., Chao E.Y. A biomechanical study of normal functional elbow motion. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:872.

15 Muller M.E., Allgower M., Schneider R., Willenegger H. Manual of Internal Fixation: Techniques Recommended by the AO-Group, 2nd ed., Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1979:387.

16 Nagy S.M.3rd, Szabo R.M., Sharkey N.A. Unilateral elbow arthrodesis: The preferred position. J. Southern Orthop. Assoc. 1999;8:80.

17 O’Neill O.R., Morrey B.F., Tanaka S., An K.N. Compensatory motion in the upper extremity after elbow arthrodesis. Clin. Orthop. 1992;281:89-96.

18 Orozco R., Giros J., Sales J.M., Videla M. A new technique of elbow arthrodesis. A case report. Int. Orthop. 1996;20:92.

19 Plank E., Spier W. Die Arthrodese des Ellenbogens. Aktuel Probl. Chir. Orthop. 1977;2:41.

20 Rashkoff E., Burkhalter W.E. Arthrodesis of the salvaged elbow. Orthopedics. 1986;9:733.

21 Ruhmann O., Schmolke S., Bohnsack M., Carls J., Flamme C., Wirth C.J. Reconstructive operations for the upper limb after brachial plexus palsy. Am. J. Orthop. 2004;33:351.

22 Snider W.J., De Witt H.J. Functional study for optimum position for elbow arthrodesis or ankylosis. Proceedings of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1973;55A:1305.

23 Spier W. Beitrag zur Technik der Druckarthrodese des Ellenbogengelenks. Monatsschr. Unfallheilkd. 1973;76:274.

24 Staples O.S. Arthrodesis of the elbow joint. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1952;34A:207.

25 Steindler A. Reconstructive Surgery of the Upper Extremity. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1923.

26 Tang C., Roidis N., Itamura J., Vaishnau S., Shean C., Stevanovic M. The effect of simulated elbow arthrodesis on the ability to perform activities of daily living. J. Hand Surg. 2001;26A:1146.

27 Wolfe S.W., Figgie M.P., Inglis A.E., Bohn W.W., Ranawat C.S. Management of infection about total elbow prostheses. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:198.