CHAPTER 33 Arthritic Disorders

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Epidemiology

AS affects 1% to 2% of whites, which is equal to the prevalence for RA. A strikingly high association between HLA-B27 and AS has been shown. HLA-B27 is present in more than 90% of white patients with AS compared with a frequency of 7% to 8% in a normal white population.1 In North American whites, with a prevalence of HLA-B27 of 7%, the frequency of AS is 0.2%.2 A positive family history of AS or related spondyloarthropathy increases the risk to 30% among HLA-B27–positive first-degree relatives compared with HLA-B27–positive control subjects (1% to 4%).3

The male-to-female ratio is reported in the range of 3:1. Women tend to be less symptomatic, however, and develop less severe disease. Women may also present more often with cervical spine disease with minimal lumbar spine symptoms. The overall pattern of illness may be similar in men and women.4

Pathogenesis

Enthesitis is the hallmark that distinguishes the spondyloarthropathies from other forms of arthritis.5 An enthesis is a dynamic structure undergoing constant modification in response to applied stress. This area is a target for inflammation. Although entheses are primarily affected in the spondyloarthropathies, inflammation of these structures is insufficient to explain the alterations that occur in joints (sacroiliac). Synovitis plays an important role. Synovitis may be a secondary event, however, after initiation with an enthesitis.6

Clinical History

The classic AS patient is a man 15 to 40 years old with intermittent dull low back pain. The associated stiffness is slowly progressive, measured in months to years. AS rarely occurs in individuals older than 50 years. Patients with spondyloarthropathy initiated after age 50 are more likely to have a non-AS spinal inflammatory disorder, such as psoriatic spondylitis.7 Back pain, which occurs throughout the disease in 90% to 95% of patients, is greatest in the morning and is increased by periods of inactivity. Patients may have difficulty sleeping because of pain and stiffness; they may awaken at night and find it necessary to leave bed and move about for a few minutes before returning to sleep. Fatigue can be a major symptom and correlates with level of disease activity, functional ability, global well-being, and mental health status.8

Back pain improves with exercise. The mode of onset is variable, with most patients developing pain in the lumbosacral region. Peripheral joints (hips, knees, and shoulders) are initially involved in a few patients, and occasionally acute iridocyclitis (eye inflammation) or heel pain may be the first manifestation of disease. Occasionally, individuals older than 50 years may present with mild symptoms despite extensive spinal involvement.9 Conversely, back pain may be severe, with radiation into the lower extremities, mimicking acute lumbar disc herniation. Patients have symptoms related to the piriformis syndrome. The belly of the piriformis muscle crosses over the sciatic nerve. Inflammation in the sacroiliac joint, where the muscle attaches, results in muscle spasm and nerve compression. There are no abnormal, persistent neurologic signs associated with the sciatic pain. The symptoms are reversible with medical therapy that relieves joint inflammation. This symptom complex of radicular pain is referred to as pseudosciatica.

Neurologic Complications

Atlantoaxial Subluxation

Neurologic complications of AS are secondary to nerve impingement or trauma to the spinal cord. In a study of 33 patients with AS and neurologic complications, cervical abnormalities were the most common cause of neurologic compromise.10 Atlantoaxial subluxation occurs in the setting of AS but less often than in RA.11 In a study of 103 AS patients, 21% had atlantoaxial subluxations. Vertical subluxation is a rare complication. About one third of patients have progression of subluxations. Five of the 22 patients with subluxation required surgical fusion.12 Rarely, symptoms of atlantoaxial subluxation may be the presenting manifestation of AS.13 Significant instability may occur without symptoms in RA because of generalized ligamentous laxity and erosion of bone. AS patients have symptoms and signs of nerve impingement more frequently in the setting of instability secondary to the immobilized state of the calcified structures surrounding the spine. Spinal cord compression is associated with myelopathic symptoms, including sensory deficits, spasticity, paresis, and incontinence.

Spinal Fracture

The other change is the loss of normal flexibility because of ankylosis of the spinal joints and ligaments. The spine in this ankylosed state is much more brittle and is prone to fracture, even with minimal trauma. The most common location for fracture is the cervical spine, although dorsal and lumbar spine fractures have also been described.14,15 The occurrence of traumatic cervical spine injury is 3.5 times greater in AS patients than in the normal population.16 The frequency of AS as the cause of spinal cord injury is 0.3% to 0.5%.17 The lower cervical spine (C6-7) is the most frequent location for fracture, which is often associated with a fall. Patients who develop fractures may complain of nothing more than localized pain and decreased or increased spinal motion, but severe sensory and motor functional loss corresponding to the location of the lesion may develop. The onset of neurologic dysfunction may be delayed for weeks after initial trauma.

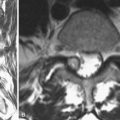

The diagnosis of fracture may be delayed because of the difficulty of detecting fractures in osteoporotic bone with plain radiographs. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of these patients may identify the location of the fracture.15 Neurologic deficits may persist despite surgical intervention in 85.7% of patients.18 A mortality rate of 35% to 50% may be found particularly in AS patients who are elderly, who have complete cord lesions, or who develop pulmonary complications after fracture.19

Laboratory Data

Laboratory results are nonspecific and add little to the diagnosis of AS. Mild anemia is present in 15% of patients. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is increased in 80% of patients with active disease. Patients with normal sedimentation rates with active arthritis may have elevated levels of C-reactive protein.20 Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody are characteristically absent. Histocompatibility testing (for HLA) is positive in 90% of AS patients but is also present in an increased percentage of patients with other spondyloarthropathies (reactive arthritis, psoriatic spondylitis, and spondylitis with inflammatory bowel disease). It is not a diagnostic test for AS. HLA testing may be useful in a young patient with early disease for whom the differential diagnosis may be narrowed by the presence of HLA-B27.

Radiographic Evaluation

Characteristic changes of AS in the sacroiliac joints and lumbosacral spine are helpful in making a diagnosis but may be difficult to determine in the early stages of the disease.21 The areas of the skeleton most frequently affected include the sacroiliac, apophyseal, discovertebral, and costovertebral joints. The disease affects the sacroiliac joints initially and then appears in the upper lumbar and thoracolumbar areas. Subsequently, in ascending order, the lower lumbar, thoracic, and cervical spine are involved. The radiographic progression of disease may be halted at any stage, although sacroiliitis alone is a rare finding except in some women with spondylitis or in men in the early stage of disease.

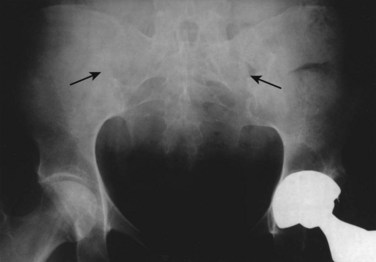

Sacroiliitis is a bilateral, symmetrical process in AS. During the next stage, the articular space becomes “pseudowidened” secondary to joint surface erosions. With continued inflammation, the area of sclerosis widens and is joined by proliferative bony changes that cross the joint space. In the final stages of sacroiliitis, complete ankylosis with total obliteration of the joint space occurs (Fig. 33–1). Ligamentous structures surrounding the sacroiliac joint may also calcify. The radiographic changes associated with sacroiliitis may be graded from 0 (normal) to 5 (complete ankylosis).

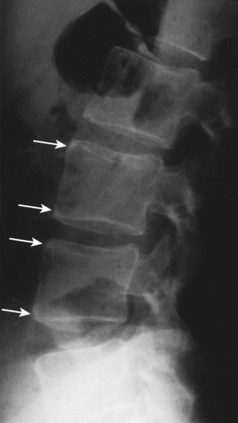

In the lumbar spine, osteitis affecting the anterior corners of vertebral bodies is an early finding. The inflammation associated with osteitis causes loss of the normal concavity of the anterior vertebral surface, resulting in a “squared” body (Fig. 33–2).

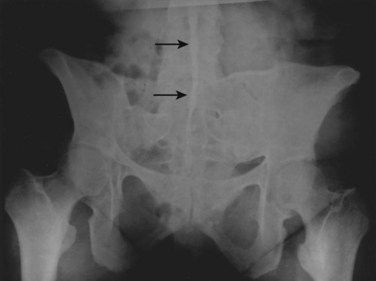

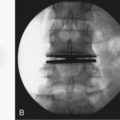

While osteopenia of the bony structures appears, calcification of disc and ligamentous structures emerges. Thin, vertically oriented calcifications of the anulus fibrosus and anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments are termed syndesmophytes. Bamboo spine is the term used to describe the spine of a patient with AS with extensive syndesmophytes encasing the axial skeleton (Fig. 33–3).

The apophyseal joints are also affected in the illness. As the disease progresses, fusion of the apophyseal joints occurs. Radiographs of the spine may show the loss of joint space and complete fusion of the joints. Cervical spine ankylosis may be particularly severe (Fig. 33–4). Complete obliteration of articular spaces between the posterior elements of C2-7 results in a column of solid bone. Patients with complete ankylosis of the apophyseal joints and syndesmophytes may develop extensive bony resorption of the anterior surface of the lower cervical vertebrae late in the course of the illness. Bone under the ligaments connecting the spinous processes may also be eroded in the setting of apophyseal joint ankylosis.

FIGURE 33–4 Ankylosing spondylitis. Lateral view of cervical spine of the patient in Figure 33–3. Radiograph shows anterior syndesmophytes (white arrows) and fusion of posterior zygapophyseal joints (black arrow).

MRI with fat saturation or contrast medium–enhanced images are able to detect early inflammatory lesions in the sacroiliac joints and the lumbar spine.22 From a diagnostic and clinical perspective, plain radiographs normally provide adequate information at a reasonable cost. Plain radiographs remain the usual radiographic technique used for the diagnosis of AS. MRI is a good choice for young women with suspected sacroiliitis as a means of decreasing radiographic exposure.

Differential Diagnosis

Two sets of diagnostic criteria exist for AS. The Rome clinical criteria, used in studies of AS, include bilateral sacroiliitis on radiologic examination and low back pain for more than 3 months that is not relieved by rest, pain in the thoracic spine, limited motion in the lumbar spine, and limited chest expansion or iritis. When the Rome criteria proved to lack sensitivity in identifying patients with spondylitis, they were modified at a New York symposium in 1966 (Table 33–1). The modified criteria included a grading system for radiographs of the sacroiliac joints in addition to limited spine motion, chest expansion, and back pain.23 Although these criteria are used mostly for studies of patient populations, they are helpful in the office setting. The European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group developed a preliminary classification system for spondyloarthropathy in general (Table 33–2).24

| Rome Criteria |

TABLE 33–2 European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group Classification: Criteria for Spondyloarthropathy

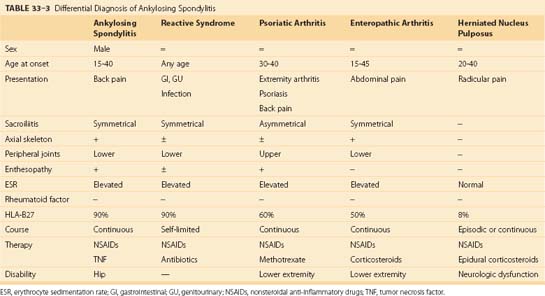

Although spondyloarthropathies are a common inflammatory musculoskeletal disorder, this group of illnesses is frequently overlooked by nonrheumatologists. A delay in diagnosis from the onset of symptoms and referral to a rheumatologist ranged from 6 to 264 months. Individuals who are misdiagnosed by primary care physicians have mild to moderate disease, with atypical presentations, and are women.25 The differential diagnosis of spinal pain includes other spondyloarthropathies and herniated intervertebral disc. Characteristics of these specific diseases are listed in Table 33–3. The inflammatory disorders are discussed briefly here.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Patients with psoriasis who develop a characteristic pattern of joint disease have psoriatic arthritis.26 The prevalence of psoriasis is 1% to 3% of the population. Classic psoriatic arthritis is described as involving distal interphalangeal joints and associated nail disease alone.27 This pattern occurs in 5% of patients. The most common form of the disease, affecting 70% of patients with psoriatic arthritis, is an asymmetrical oligoarthritis; a few large or small joints are involved. Dactylitis, diffuse swelling of a digit, is most closely associated with this form of the disease. Skin activity and joint symptoms do not correlate, and patients with little skin activity may experience continued joint pain and stiffness.

Spondylitis on radiographs is characterized by asymmetrical involvement of the vertebral bodies and nonmarginal syndesmophytes. Joint ankylosis occurs less commonly than in AS. Of patients, 25% can have sacroiliac involvement manifested by sacroiliitis, which can be unilateral or bilateral. Symmetrical involvement—from side to side and severity of disease—predominates over asymmetrical disease. Sacroiliitis may occur without spondylitis. Spinal disease progression occurs in a random rather than orderly fashion, ascending the spine as commonly noted in AS. Cervical spine disease may occur in the absence of sacroiliitis or lumbar spondylitis. Alterations in the cervical spine include joint space sclerosis and narrowing and anterior ligamentous calcification (Fig. 33–5).

Treatment of psoriatic arthritis is similar to treatment of RA. Immunosuppressive agents and TNF-α inhibitors are indicated for the treatment of peripheral arthritis.28 The benefits for axial disease are being studied. Patients with psoriatic arthritis develop varying degrees of restriction of spinal motion. There is no consistent correlation between the severity of peripheral joint and axial skeletal disease. Rarely, patients with psoriatic arthritis may develop atlantoaxial subluxation with evidence of cervical myelopathy. Fracture after minor trauma may be overlooked for an extended period.29 This disease should be treated early and aggressively.30

Reactive Arthritis

Reactive arthritis is associated with HLA-B27 in 60% to 80% of individuals. The classic patient with reactive arthritis is a young man about 25 years old who develops urethritis and a mild conjunctivitis, followed by the onset of a predominantly lower extremity oligoarthritis. The conjunctivitis is usually mild and is manifested by an erythema (redness) and crusting of the lids. Arthritis may occur 1 to 3 weeks after the initial infection. In many patients, arthritis is the only manifestation of disease.31 Back pain is a frequent symptom of patients with reactive arthritis. During the acute course, 31% to 92% of patients may develop pain in the lumbosacral region. Occasionally, the pain radiates into the posterior thighs but rarely below the knees; it may be unilateral. This finding corresponds to the asymmetrical involvement of the sacroiliac joints and is in contrast to the symmetrical involvement of AS.32 Spondylitis affecting the lumbar, thoracic, and cervical spine occurs less commonly than sacroiliitis, with 23% of patients with severe disease showing such involvement.33 Neck pain is a rare symptom of patients with reactive arthritis. Constitutional symptoms occur in about one third of patients and include fever, anorexia, weight loss, and fatigue.

The joint and enthesopathic manifestations of reactive arthritis seem to respond better to newer NSAIDs than to aspirin. The drugs are continued as long as the patient remains symptomatic. Oral corticosteroids are less effective in this polyarthritis compared with RA. The role of antibiotic therapy in the acute phase of reactive arthritis is controversial. Antibiotics may be ineffective for Chlamydia-associated reactive arthritis.34 Sulfasalazine has been reported to improve spinal pain and swollen joints in patients with reactive arthritis. The usual dose of sulfasalazine is 2 g/day in divided doses. The immunosuppressive methotrexate is reserved for patients with uncontrolled progression of joint disease and unresponsive, extensive skin involvement. The dose of methotrexate ranges from 7.5 to 25 mg/wk.

Enteropathic Arthritis

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease are inflammatory bowel diseases. Ulcerative colitis is limited to the colon; Crohn disease, or regional enteritis, may involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract.35 Inflammation of the gut results in numerous gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, fever, and weight loss. These inflammatory diseases are also associated with extraintestinal manifestations, including arthritis. Articular involvement in inflammatory bowel disease includes peripheral and axial skeleton joints. Peripheral arthritis is generally nondeforming and follows the activity of the underlying bowel disease.36 Axial skeleton disease is similar to AS and follows a course independent of activity of bowel inflammation.

The radiographic changes of spondylitis in inflammatory bowel disease are indistinguishable from classic AS (Fig. 33–6). Findings include squaring of vertebral bodies; erosions; widening and fusion of the sacroiliac joints; symmetrical involvement of sacroiliac joints; and marginal syndesmophytes involving the lumbar, thoracic, or cervical spine.

The factors that help make the diagnosis of enteropathic spondyloarthropathy are the pattern of peripheral arthritis if present (upper extremity disease is uncommon in AS and reactive arthritis; bilateral ankle arthritis is uncommon in psoriatic disease), erythema nodosum, and iritis. Therapy for enteropathic spondylitis is similar to therapy for classic AS. TNF-α inhibitors are effective agents for the bowel and articular disease.37

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is another disease that may occur in the setting of spondylitis. Patients with AS and DISH should be easily differentiated by careful radiographic evaluation.38 DISH may cause alterations of the sacroiliac joints.39 CT of the sacroiliac joints differentiates the hyperostotic joint changes from changes associated with joint erosion and fusion (Fig. 33–7). Also of note is the occurrence of fracture in patients with DISH and patients with AS. The convergence of two common diseases in the same host, a middle-aged man, is likely. The occurrence of AS and DISH of the cervical spine has been reported.40

Treatment

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

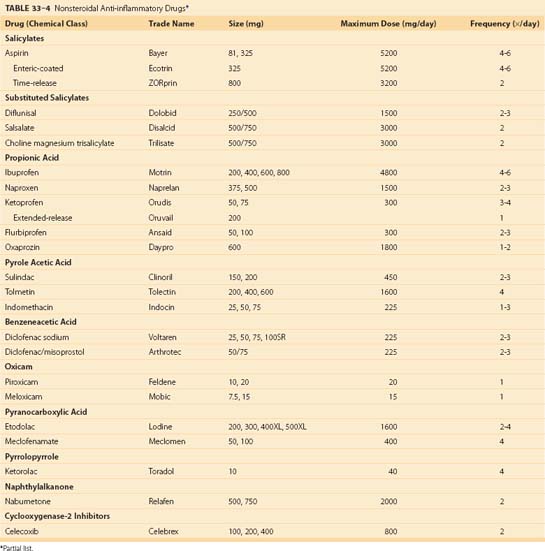

Medications to control pain and inflammation are useful to patients with AS. NSAIDs possess antipyretic, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory characteristics. They are anti-inflammatory and analgesic when given long-term in larger doses. Table 33–4 lists NSAIDs currently available for the treatment of spinal disorders. NSAIDs are effective at decreasing pain and improving movement but have not been proven to slow the progression of disease. The benefits of NSAIDs must be balanced against potential toxicities.41

Cyclooxygenase Inhibitors

COX-2 inhibitors are a class of NSAIDs that have efficacy equal to COX-1 inhibitors (aspirin, naproxen) with less gastrointestinal toxicity (see Table 33–4). The cardiovascular risk associated with these agents is an active area of research. COX-2 inhibitors should be considered for individuals with increased risks of gastrointestinal bleeding, exclusively. COX-2 inhibitors are effective in osteoarthritis and RA. AS patients were reported to be responsive to celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, in a 6-week controlled study.42

Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Inhibitors

TNF-α, an inflammatory cytokine, is associated with the inflammatory process that results in the phenotypic expression of AS. Anti–TNF-α therapies are available in the form of infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab, which inhibit the inflammatory effects of TNF-α. Infusion of intravenous infliximab, 5 mg/kg at 0, 2, and 6 weeks, in a placebo-controlled trial resulted in improvement in axial symptoms and signs, enthesitis, and peripheral arthritis.43 Open-label extensions of studies for 54 weeks have documented persistent improvement with infliximab infusions at 6-week intervals.44 In a placebo-controlled, 4-month study of 40 AS patients taking 25 mg of etanercept, 80% of patients receiving the active drug experienced an improvement in morning stiffness, enthesitis, quality of life, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or C-reactive protein.45

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved etanercept, 25 mg twice a week, for the treatment of AS. Repeated infusions of infliximab remain effective in AS over a 12-month period.46 The full benefits of anti–TNF-α therapy in AS remain to be determined. The efficacy of these agents in disease of long duration is less certain. These agents are expensive, and their availability is limited. Toxicities are associated with their use, including the activation of latent tuberculosis.

Prognosis

The general course of AS is benign and is characterized by exacerbations and remissions. Many patients with AS may have sacroiliitis with mild involvement of the lumbosacral spine. Limitation of lumbosacral motion may be mild. The disease can become quiescent at any time. Patients who go on to develop total fusion of the spine may feel better because ankylosis of the spinal joints is associated with decreased pain. In a study of 1492 patients for 2 years, the frequency of patients with a total remission of disease was less than 2%.47

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Epidemiology

The prevalence of RA is 1% to 3% of the U.S. population.1 RA is found in all racial and ethnic groups. The condition occurs in all age groups but is most common in adults 40 to 70 years old.48 The male-to-female ratio is approximately 1:3. Symptoms of cervical spine disease occur in 40% to 80% of RA patients. Radiographic evidence of cervical spine involvement is found in 86% of RA patients, whereas neurologic symptoms from cervical spine disease occur less frequently in 10% of patients with radiographic changes. Cervical spine disease usually occurs in the setting of active peripheral disease; however, occasionally neck symptoms may be the initial or predominant symptom without clinical signs of RA in other locations. The lumbar spine is rarely involved in the rheumatoid process. One study suggested that 5% of men and 3% of women with RA have lumbar spine involvement.49

Pathogenesis

RA is a chronic immune-mediated disease whose initiation and perpetuation are dependent on T lymphocyte response to unknown antigens.50 Increased numbers of CD4+ lymphocytes that activate B lymphocytes to produce immunoglobulin are frequently found in synovium from RA patients. The activation of macrophages results in the production of monokines, including TNF-α, and interleukin-1. These factors attract additional lymphocytes and neutrophils. Angiogenesis factors result in the growth of new capillaries. Synovial cells cause tissue destruction by release of activated metalloproteinases, including procollagenase and progelatinase. The inflammatory response is also enhanced by the production of arachidonic acid metabolites.

Cervical Subluxation

Luxation of the atlantoaxial joint may occur anteriorly, posteriorly, superiorly or vertically, or laterally. Anterior subluxation is the most common form and results from insufficiency of the transverse ligament or fracture of the odontoid and occurs in 49% of patients.51 Posterior subluxation occurs when C1 moves posteriorly on C2 and results from erosion or fracture of the odontoid and occurs in 7% of patients. Vertical or superior subluxation results from destruction of the lateral atlantoaxial joints around the foramen magnum and is found in 38% of patients. Lateral subluxation occurs in 20% with erosion of the lateral mass and odontoid. Abnormal motion of this joint in any direction may result in compression of the cervical spinal cord or medulla oblongata, resulting in the development of neurologic symptoms and signs of myelopathy, including paresthesias, muscle weakness, reflex changes, spasticity, and incontinence. Subluxation of the atlantoaxial joint by the odontoid process of the axis and the posterior arch of the atlas may compress the vertebral arteries. The vertebral arteries are compressed as they travel through the foramina in the transverse processes of C1 and C2. Vertebral artery compression may cause tetraplegia, coma, or sudden death.52

Subluxation may occur between cervical vertebrae below the atlantoaxial joint. Common levels include C3-4 and C4-5. Inflammation in the zygapophyseal joints and surrounding bursae undermines the stability of these joints, resulting in excessive motion and angulation of the cervical spine.53 Intervertebral discs may be invaded by growing synovial tissue, resulting in disc space narrowing. The reported frequency of subaxial subluxation ranges from 7% to 29% of RA patients.54

Myelopathy may also occur in patients without atlantoaxial or cervical spine subluxation. In these patients, synovitis from the zygapophyseal joints along with intervertebral disc lesions may compromise the blood supply to the spinal cord through stenosis of vertebral vessels that feed the anterior spinal artery. Ischemic myelopathy is the result. Sudden death may also be a consequence of thrombosis of vertebral vessels.55

Clinical History

Neck movement frequently precipitates or aggravates neck pain that is aching and deep in quality. Atlantoaxial disease is experienced in the upper part of the cervical spine, and pain radiates over the occiput into the temporal and frontal regions with increasing disease of the C1-2 joint. Occipital headaches are frequently associated with active rheumatoid involvement of the cervical spine. Other symptoms of C1-2 subluxation include a sensation of the head falling forward with flexion of the neck, loss of consciousness or syncope, incontinence, dysphagia, vertigo, convulsions, hemiplegia, dysarthria, nystagmus, or peripheral paresthesias.56 Peripheral joint erosion is a harbinger of C1-2 subluxation. Development of cervical subluxation occurs in patients who have joint erosions of hands and feet, serum rheumatoid factor, and subcutaneous nodules.

Pain associated with RA in the subaxial segments of the cervical spine is located in the lateral aspects of the neck and clavicles (C3-4) and over the shoulders (C5-6). Neurologic symptoms include paresthesias and numbness. Paresthesias have a burning quality that may be attributed to an entrapment neuropathy (carpal tunnel syndrome) but is sufficiently different not to be confused with joint pain. Patients with sensory symptoms alone may have their symptoms ascribed to arthritis, delaying the diagnosis of cervical myelopathy.52

Physical Examination

Physical examination of a patient with RA with cervical spine disease reveals diffuse peripheral joint involvement characterized by heat, swelling, bogginess, tenderness, and loss of motion. Nodules over the extensor surfaces are noted in 20% of RA patients. Examination of the cervical spine may show tenderness with palpation over the bony skeleton and limitation of all spinal movements. Inspection may show fixation of the head tilted down and to one side. This lateral tilt is caused by the asymmetrical destruction of the lateral atlantoaxial joints. Normal cervical lordosis may also be absent. With the neck flexed, the spinous process of the axis may be prominent in the midline of the neck of a patient with atlantoaxial subluxation. Patients with subaxial subluxation may show abnormalities in the upper extremities. Compression of C6-8 segments causes distinctive numb, clumsy hands and tactile agnosia.57 Neurologic abnormalities are seen in approximately 7% of RA patients.

Laboratory Data

Abnormal laboratory findings include anemia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and increases in serum globulin levels. Thrombocytosis is found in patients with active RA. Rheumatoid factors (antibodies directed against host antibodies) are present in 80% of patients with RA. Antinuclear antibodies are present in 30% of RA patients. C-reactive protein, an acute-phase reactant, may be helpful when obtained in a serial manner to predict individuals who are at increased risk for joint deterioration and as a measure of response to therapy. Individuals with persistent elevations in C-reactive protein are at risk of progressive cervical spine subluxations.58 Synovial fluid analysis shows inflammatory fluid characterized by poor viscosity, increased numbers of white blood cells, decreased glucose level, and increased protein level.

Radiographic Evaluation

The radiographic criteria for the diagnosis of RA cervical spine disease as proposed by Bland and colleagues59 are (1) atlantoaxial subluxation of 2.5 mm or more; (2) multiple subluxation of C2-3, C3-4, C4-5, and C5-6; (3) narrow disc spaces with little or no osteophytosis; (4) erosion of vertebrae, especially vertebral plates; (5) odontoid, small, pointed, eroded loss of cortex; (6) basilar impression; (7) apophyseal joint erosion and blurred facets; (8) cervical spine osteoporosis; (9) wide space (>5 mm) between posterior arch of the atlas and spinous process of the axis (flexion to extension); and (10) secondary osteosclerosis, atlantoaxial occipital complex, which may indicate local degenerative change. The normal distance between the odontoid and atlas is 2.5 mm in women and 3 mm in men as measured from the posteroinferior aspect of the tubercle of C1 to the nearest point on the odontoid (Fig. 33–8).60 The posterior atlanto-odontoid interval is the remaining distance between the posterior surface of the odontoid process and the anterior edge of the posterior ring of the atlas. RA patients with a posterior interval of more than 14 mm did not have neurologic deficits. Posterior subluxation may also occur if the atlas “jumps” over the axis, resting in a dorsal position resulting in posterior subluxation. Vertebrobasilar artery insufficiency associated with neurologic dysfunction is a manifestation of this form of subluxation.

In addition to changes in the upper cervical spine, radiographic abnormalities, including subaxial subluxation, apophyseal joint narrowing, and disc space narrowing, occur in the lower cervical spine. Subaxial subluxation is present in instances of malalignment of more than 3.5 mm. The stability of flexion and extension of the lower cervical spine depends on the integrity of the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments. Greater than 3.5 mm of malalignment is indicative of a mechanically unstable spine. Multiple subluxations may occur, producing a “staircase” appearance on lateral radiographs. Anterior subluxation is more frequent than posterior subluxation. Subaxial subluxation is most notable on a lateral flexion view of the cervical spine (Fig. 33–9). Apophyseal joint disease includes narrowing, erosions, and sclerosis. Disc destruction in the cervical spine is associated with disc space narrowing and is caused by extension of erosive disease from uncovertebral joints or by ongoing trauma to vertebral endplates secondary to instability. The final stage of apophyseal disease is fibrous ankylosis of one or more levels, which may rarely simulate the appearance of AS.

MRI is a noninvasive method that is useful in detecting soft tissue abnormalities in the cervical spine of RA patients. It is able to detect pannus around the odontoid and alterations in the substance of the spinal cord. MRI may also be useful in documenting the response of pannus to therapy or the status of the spinal cord in the postoperative state. Compared with CT and plain radiographs, MRI with plain radiographs shows lytic lesions and odontoid erosions and vertical atlantoaxial subluxations more often, shows anterior subluxations as often, and shows lateral subluxations less often.61

Differential Diagnosis

RA is a clinical diagnosis based on history of joint pain, distribution of joint involvement, and characteristic laboratory abnormalities (rheumatoid factor). Criteria for the classification of RA were published by the American College of Rheumatology (Table 33–5).62 In the setting of generalized, active disease, the finding of neck pain associated with multiple abnormalities, including atlantoaxial subluxation, apophyseal joint erosion without sclerosis, disc space narrowing without osteophytes, and multiple subluxations, is most appropriately attributed to RA. The cervical spine abnormalities of AS, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, enteropathic arthritis, osteoarthritis, and DISH are associated with new bone formation or ligamentous calcification that differentiate them from RA. Occasionally, atlantoaxial subluxation may occur alone in the setting of little peripheral disease. In those circumstances, other disease processes that may cause subluxation include AS, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, trauma, or local infection.

TABLE 33–5 American Rheumatism Association 1987 Revised Criteria for Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis*

| 1. Morning stiffness | Morning stiffness in and around joints, lasting at least 1 hr before maximal improvement |

| 2. Arthritis of three or more joint areas | At least 3 joint areas simultaneously have soft tissue swelling or fluid (not bony overgrowth) |

| 3. Arthritis of hand | At least 1 area swollen (as defined above) in a wrist, metacarpophalangeal, or proximal interphalangeal joint |

| 4. Symmetrical arthritis | Simultaneous involvement of proximal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, or metatarsophalangeal joints is acceptable without absolute symmetry |

| 5. Rheumatoid nodules | Subcutaneous nodules, over bony prominences, extensor surfaces, or juxta-articular regions, observed by a physician |

| 6. Serum rheumatoid factor | Demonstration of abnormal amounts of serum rheumatoid factor by any method for which result has been positive in <5% of normal control subjects |

| 7. Radiographic changes | Radiographic change typical of rheumatoid arthritis on posteroanterior hand and wrist radiographs, which must include erosions or unequivocal bony decalcification localized in or most marked adjacent to involved joints (osteoarthritis changes alone do not qualify) |

* For classification purposes, a patient is said to have rheumatoid arthritis if the patient has satisfied at least 4 of 7 criteria. Criteria 1 through 4 must have been present for at least 6 wk. Patients with 2 clinical diagnoses are not excluded. Designation as classic, definite, or probable rheumatoid arthritis is not made.

From Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Block DA, et al: The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 31:315, 1988.

Treatment

The treatment of RA has undergone a paradigm shift with the advent of new drug therapies directed at control of the factors that mediate the immunologic destruction of joints.48,63 The previous approach involved an initial conservative approach with few medications prescribed until definite erosions were documented. The treatment for control of generalized RA included a regimen of patient education, physical therapy, NSAIDs, remittive agents (gold, salts, penicillamine, or hydroxychloroquine), corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive agents (methotrexate). The therapy has been organized into a therapeutic pyramid based on the use of less toxic therapies for all patients. Drugs of greater toxicity were added with increasing clinical activity of disease.

A reassessment of the treatment regimen was proposed when additional therapies became available.64 This regimen initiated therapy with a multitude of drugs of increased toxicity compared with NSAIDs, with the proposition that the increased morbidity and mortality rates of RA require aggressive initial therapy. The difficulty was the absence of new medicines to control the disorder better. The advent of new agents has offered the opportunity to be more aggressive in preventing lesions before disability occurs.

The American College of Rheumatology has reviewed the available therapies and has proposed new options for the treatment of RA.65 These new guidelines include data supporting the use of biologic agents in the therapy for RA.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Medications to control pain and inflammation are useful in patients with RA (see Table 33–4). The choice of agent depends on numerous factors, including drug half-life, formulation, dose range, and tolerability. COX-2 inhibitors are a class of NSAIDs that have efficacy equal to COX-1 inhibitors (aspirin, naproxen) with less gastrointestinal toxicity. COX-2 inhibitors are effective in RA and are associated with fewer gastrointestinal toxicities.66,67 These agents should be limited to RA patients with increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding until the degree of cardiovascular risk is quantified.

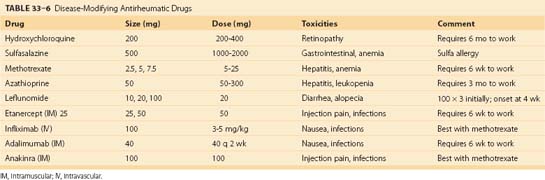

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

Patients who continue to have joint inflammation or who exhibit joint damage (joint space narrowing, bony erosions, or cysts) despite adequate NSAID therapy are candidates for remittive therapy. Remittive agents have a delayed onset of action compared with NSAIDs. Table 33–6 lists DMARDs used for the treatment of RA. Methotrexate at doses of 7.5 to 25 mg/wk is effective in decreasing the inflammation of RA and may slow disease progression. Methotrexate may be given all at once during the week. It is effective over a long duration of therapy.

Leflunomide is an oral pyrimidine inhibitor used to treat RA.68 The dose is 100 mg for 3 days, than 20 mg or 10 mg daily as tolerated. Toxicities include abnormal liver function tests and diarrhea. Leflunomide and methotrexate can be used together. These patients need to be monitored closely for potential hepatotoxicity.48

Systemic corticosteroids are effective in controlling the inflammatory components of RA. Corticosteroids are the most powerful and predictable remedy inducing immediate relief of joint inflammation in RA. Corticosteroids at low doses (5 to 10 mg) have a modest effect on reducing the rate of radiologically detected joint destruction. A prospective trial showed disease-modifying properties of 10 mg of prednisone over a 2-year period.69 Corticosteroids are also associated with a wide range of toxicities, from hypertension and diabetes to cataracts and obesity.

Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Inhibitors

Infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab inhibit the inflammatory effects of TNF-α and are efficacious in the treatment of RA. Infliximab is partly humanized mouse monoclonal antibody directed against TNF-α. It is administered intravenously. Infliximab is added to methotrexate to limit the production of neutralizing antibodies to the mouse component of the agent. In a 30-week trial, combined infliximab and methotrexate was more effective than methotrexate alone in patients with active RA.70 In a 54-week study, infliximab, 3 mg or 10 mg/kg, and a stable dose of methotrexate prevented radiographic progression to a greater degree than methotrexate alone.71

Etanercept is a recombinant form of the p75 TNF receptor fusion protein. Etanercept, 25 mg, is administered by subcutaneous injection twice weekly or 50 mg once a week. Etanercept is more effective than placebo in limiting joint activity in RA.72 It is also effective and safe when added to methotrexate.73 This drug is also effective over a 12-month period.74

Adalimumab is a fully human monoclonal TNF-α antibody given by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks at a dose of 40 mg. This anti–TNF-α factor is effective with methotrexate in decreasing joint activity.75 The concern with anti–TNF-α therapies are the toxicities. Blocking TNF-α increases the risk for serious infection. TNF-α helps to maintain containment of organisms in granulomas. Inhibition of TNF-α has been associated with the reactivation of tuberculosis.76,77

Anakinra is a recombinant, nonglycosylated form of human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. This agent works by competitively inhibiting IL-1 from binding to its receptor site. Anakinra, 100 mg, is given as a daily subcutaneous injection. It has been shown to be an effective agent in combination with methotrexate in the improvement of RA.78,79

Cervical Spine Therapy

Conservative treatment of RA of the cervical spine is supportive. Early aggressive medical management is important to prevent joint destruction. Early DMARD therapy results in better outcomes. Combination therapy used early in the course of RA can limit the development of atlantoaxial and vertical subluxations. Sulfasalazine, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and prednisolone were more effective than a single DMARD with prednisolone in preventing cervical subluxation.80 Soft cervical collars offer comfort but do not protect against progressive subluxations. Rigid collars can limit anterior subluxations but do not allow reduction of the subluxations in extension. They are poorly tolerated by RA patients with temporomandibular disease.81

Prognosis

The course of RA cannot be predicted at time of onset. Some patients develop sustained disease that is associated with joint destruction and resistance to therapy. Patients who are older with seropositive generalized disease with nodules are at greater risk of developing cervical spine disease. Not all patients develop subluxation. In a 5- to 14-year follow-up study, 25% of patients had an increase in subluxation, 50% had no change, and 25% had improvement. In a 5-year study of 106 RA patients, the prevalence of cervical spine subluxation increased from 43% to 70%. In subaxial disease, myelopathy was associated with narrowing of the canal, destruction of spinous processes, axial shortening, younger age of patient, longer duration of disease, higher dose of corticosteroids, and higher stage of disease. Sudden death remains a complication of RA cervical spine disease, particularly in patients with vertical subluxation. Individuals with subluxations had eight times the mortality as RA patients without subluxations.82

Pearls

1 Al-Khonizy W, Reveille JD. The immunogenetics of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Ballieres Clin Rheumatol. 1998;12:567-588.

2 American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis Guidelines. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:328-346.

This current listing of new therapies for RA highlights the importance of early aggressive therapy.

3 Braun J, Bollow M, Sieper J. Radiologic diagnosis and pathology of the spondyloarthropathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1998;24:697-735.

4 Khan MA. Update on spondyloarthropathies. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:896-907.

5 Reiter MF, Boden SD. Inflammatory disorders of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23:2755-2766.

1 Schlosstein L, Terasaki PI, Bluestone R, et al. High association of an HL antigen, W27, with ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:704-706.

2 Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:58-67.

3 Reveille JD, Ball EJ, Khan MA. HLA-B27 and genetic predisposing factors in spondyloarthropathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:265-272.

4 Gran JT, Ostensen M. Spondyloarthritides in females. Ballieres Clin Rheumatol. 1998;12:695-715.

5 Braun J, Khan MA, Siepper J. Enthesitis and ankylosis in spondyloarthropathy: What is the target of the immune response? Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:985-994.

6 McGonagle D, Gibbon W, Emery P. Classification of inflammatory arthritis by enthesitis. Lancet. 1998;352:1137-1140.

7 Caplanne D, Tubach F, Le Parc JM. Late onset spondyloarthropathy: Clinical and biological comparison with early onset patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:176-179.

8 Van Tubergen A, Coenen J, Landewe R, et al. Assessment of fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A psychometric analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:8-16.

9 Mader R. Atypical clinical presentations of ankylosing spondylitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1999;29:191-196.

10 Fox MW, Onofrio BM, Kilgore JE. Neurological complications of ankylosing spondylitis. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:871-878.

11 Sorin S, Askari A, Moskowitz RW. Atlantoaxial subluxation as a complication of early ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1979;22:273-276.

12 Ramos-Remus C, Gomez-Vargas A, Hernandez-Chavez A, et al. Two-year follow-up of anterior and vertical atlantoaxial subluxations in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:507-510.

13 Hamilton MG, MacRae ME. Atlantoaxial dislocation as the presenting symptom of ankylosing spondylitis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;18:2344-2346.

14 Broom MJ, Raycroft JF. Complications of fractures of the cervical spine in ankylosing spondylitis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988;13:763-766.

15 Iplikcioglu AC, Bayar MA, Kokes F, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in cervical trauma associated with ankylosing spondylitis: Report of two cases. J Trauma. 1994;36:412-413.

16 Detwiler KN, Loftus CM, Godersky JC, et al. Management of cervical spine injuries in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:210-215.

17 Bohlman HH. Acute fractures and dislocations of the cervical spine: An analysis of three hundred hospitalized patients and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:1119-1142.

18 Rowed DW. Management of cervical spinal cord injury in ankylosing spondylitis: The intervertebral disc as a cause of cord compression. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:241-246.

19 Foo D, Sarkarati M, Marcelino V. Cervical spinal cord injury complicating ankylosing spondylitis. Paraplegia. 1985;23:358-365.

20 Spoorenberg A, van der Heijde D, de Klerk E, et al. Relative value of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in assessment of disease activity in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:980-984.

21 McEwen C, DiTata D, Ling GC, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis and spondylitis accompanying ulcerative colitis, regional enteritis, psoriasis, and Reiter’s disease: A comparative study. Arthritis Rheum. 1971;14:291-318.

22 Bollow M, Enzweiler C, Taupitz M, et al. Use of contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to detect spinal inflammation in patients with spondyloarthritides. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(Suppl 28):S167-S174.

23 Bennett PH, Wood PHN. Population studies of the rheumatic diseases. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium. New York: Amsterdam, Excerpta Medica; 1966:456. 1968

24 Khan MA, van der Linden SM. A wider spectrum of spondyloarthropathies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1990;20:107-113.

25 Boyer GS, Templin DW, Bowler A, et al. A comparison of patients with spondyloarthropathy seen in specialty clinics with those identified in a communitywide epidemiologic study. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2111-2117.

26 Cohen MR, Reda DJ, Clegg DO. Baseline relationships between psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Analysis of 221 patients with active psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1752-1756.

27 Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1998;24:829-844.

28 Mease P. Psoriatic arthritis: The role of TNF inhibition and the effect of its inhibition with etanercept. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(Suppl 28):S116-S121.

29 Sosner J, Fast A, Kahan BS. Odontoid fracture and C1-C2 subluxation in psoriatic cervical spondyloarthropathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:519-521.

30 Gladman DD. Natural history of psoriatic arthritis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1994;8:379-394.

31 Arnett FC, McClusky E, Schacter BZ, et al. Incomplete Reiter’s syndrome: Discriminating features and HLA-W27 in diagnosis. Ann Intern Med. 1976;84:8-12.

32 Russell AS, Davis P, Percy JS, et al. The sacroiliitis of acute Reiter’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1977;4:293-296.

33 Good AE. Reiter’s syndrome: Long-term follow-up in relation to development of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1979;38:39-45.

34 Beutler AM, Hudson AP, Whittum-Hudson JA, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis can persist in joint tissue after antibiotic treatment in chronic Reiter’s syndrome/reactive arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 1997;3:125-130.

35 Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:417-429.

36 Orchard TR, Wordsworth BP, Jewell DP. Peripheral arthropathies in inflammatory bowel disease: Their articular distribution and natural history. Gut. 1998;42:387-391.

37 Van den Bosch F, Kruithof E, De Vos M, et al. Crohn’s disease associated with spondyloarthropathy: Effect of TNF-α blockade with infliximab on the articular symptoms. Lancet. 2000;356:1821-1822.

38 Yagan R, Khan MA. Confusion of roentgenographic differential diagnosis of ankylosing hyperostosis (Forestier’s disease) and ankylosing spondylitis. Spine State Art Rev. 1990;4:561-572.

39 Durback MA, Edelstein G, Schumacher HRJr. Abnormalities of the sacroiliac joints in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: Demonstration by computed tomography. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1506-1511.

40 Williamson PK, Reginato AJ. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis of the cervical spine in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:570-573.

41 Miceli-Richard C, Dougados M. NSAIDs in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(Suppl 28):S65-S66.

42 Dougados M, Behier JM, Jolchine I, et al. Efficacy of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2-specific inhibitor, in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: A six-week controlled study with comparison against placebo and against a conventional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:180-185.

43 Van den Bosch F, Kruithof E, Baeten D, et al. Randomized double-blind comparison of chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor alpha (infliximab) versus placebo in active spondyloarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:755-765.

44 Brandt J, Sieper J, Braun J. Infliximab in the treatment of active and severe ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(Suppl 28):S106-S110.

45 Gorman JD, Sack KE, David JCJr. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis by inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1349-1356.

46 Kruithof E, vanden Bosch F, Baeten D, et al. Repeated infusions of infliximab, a chimeric anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody, in patients with active spondyloarthropathy: One year followup. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:207-212.

47 Kennedy LG, Edmunds L, Calin A. The natural history of ankylosing spondylitis: Does it burn out? J Rheumatol. 1993;20:688-692.

48 Lee DM, Weinblatt ME. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2001;358:903-911.

49 Lawrence JS, Sharp J, Ball J, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis of the lumbar spine. Ann Rheum Dis. 1964;23:205-217.

50 Panayi GS. The immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32(Suppl 1):4-14.

51 Reiter MF, Boden SD. Inflammatory disorders of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23:2755-2766.

52 Zeidman SM, Ducker TB. Rheumatoid arthritis: Neuroanatomy, compression, and grading of deficits. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:2259-2266.

53 Yonezawa T, Tsuji H, Matsui H, Hirano N. Subaxial lesions in rheumatoid arthritis: Radiographic factors suggestive of lower cervical myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:208-215.

54 Halla JT, Hardin JG, Vitek J, et al. Involvement of the cervical spine in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:652-659.

55 Webb F, Hickman J, Brew D. Death from vertebral artery thrombosis in rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ. 1968;2:537-538.

56 Gordon DA, Hastings DE. Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al, editors. Rheumatology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003:765-780.

57 Chang MH, Liao KK, Cheung SC, et al. “Numb, clumsy hands” and tactile agnosia secondary to high cervical spondylotic myelopathy: A clinical and electrophysiological correlation. Acta Neurol Scand. 1992;86:622-625.

58 Fujiwara K, Fujimoto M, Owaki H, et al. Cervical lesions related to the systemic progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Spine. 1998;23:2052-2056.

59 Bland JH, Van Buskirk FW, Tampas JP, et al. A study of roentgenographic criteria for rheumatoid arthritis of the cervical spine. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1965;95:949-954.

60 Komusi T, Munro T, Harth M. Radiologic review: The rheumatoid cervical spine. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1985;14:187-195.

61 Oostveen JCM, van de Laar MAFJ. Magnetic resonance imaging in rheumatic disorders of the spine and sacroiliac joints. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2000;30:52-69.

62 Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Block DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315.

63 Choy EHS, Panayi GS. Cytokine pathways and joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:907-916.

64 Wilske KR, Healey LA. Remodeling the pyramid, a concept whose time has come. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:565-566.

65 American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid. Arthritis guidelines: Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:328-346.

66 Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520-1528.

67 Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: The CLASS study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284:1247-1255.

68 Kremer JM. Rational use of new and existing disease-modifying agents in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:695-706.

69 Van Everdingen AA, Jacobs JWG, van Reesema DRS, et al. Low-dose prednisone therapy for patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis: Clinical efficacy, disease-modifying properties, and side effects. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:1-12.

70 Maini R, St. Clair EW, Breedveld F, et al. Infliximab (chimeric anti-tumor necrosis factor α monoclonal antibody) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate: A randomized phase III trial. Lancet. 1999;354:1932-1939.

71 Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DMFM, St. Clair EW, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1594-1602.

72 Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:478-486.

73 Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Bankhurst AD, et al. A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor: Fc fusion protein in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:253-259.

74 Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1586-1593.

75 Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, et al. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: The ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:35-45.

76 Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor α-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1098-1104.

77 Baghai M, Osmon DR, Wolk DM, et al. Fatal sepsis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with etanercept. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:653-656.

78 Cohen S, Hurd E, Cush J, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with anakinra: A recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, in combination with methotrexate: Results of a twenty-four-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:614-624.

79 Bresnihan B, Alvaro-Gracia JM, Cobby M, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:2196-2204.

80 Neva MH, Kauppi MJ, Kautiainen H, et al. Combination drug therapy retards the development of rheumatoid atlantoaxial subluxations. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2397-2401.

81 Kauppi M, Anttila P. A stiff collar can restrict atlantoaxial instability in rheumatoid atlantoaxial subluxations. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:771-774.

82 Riise T, Jacobsen BK, Gran JT. High mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and atlantoaxial subluxations. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:2425-2429.