CHAPTER 44 ARTERIOVENOUS MALFORMATIONS OF THE BRAIN AND SPINAL CORD

An arteriovenous malformation (AVM) consists of one or more arteriovenous shunts, which corresponds to an abnormal capillary bed with a shortened arteriovenous transit time. Two broad categories of arteriovenous shunts can be recognized: AVMs and arteriovenous fistulae (AVFs). AVMs are characterized by a network of abnormal channels (nidi) between the arterial feeders and the draining veins. AVFs, in contrast, consist of a direct communication or opening between a feeding artery and a draining vein. AVMs and AVFs are the two basic forms of arteriovenous shunts that can be found throughout the central nervous system.

In the past, most AVMs were diagnosed during clinically recognized episodes. The access to imaging facilities has allowed their preclinical diagnosis. Follow-up of this incidentally discovered population of patients with AVMs suggests that the clinical course is more benign than previously believed. The classic postulate that AVMs are congenital malformations, hence implying their presence at birth, has not been supported by antenatal or pediatric imaging. On the contrary, it is likely that lesions found in young adults, although probably resulting from an early in utero “event,” are not present at birth. Pediatric cases or even neonatal series represent only a small portion of the cases and pertain to specific disease groups (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia [HHT], vein of Galen malformations, pial AVFs).1

BRAIN ARTERIOVENOUS MALFORMATION

Incidence

The prevalence of brain AVMs (BAVMs) in a given population is difficult to estimate. It is believed that between 0.14% and 0.8% of the population may present with a BAVM in a given year.2,3 The variation in statistics results from studies of disparate populations, ranging from the residents in a small community4 to subjects of autopsy series.3 As previously alluded to, these numbers represent data collected before the era of noninvasive high-quality imaging modalities.

Classification and Angioarchitecture

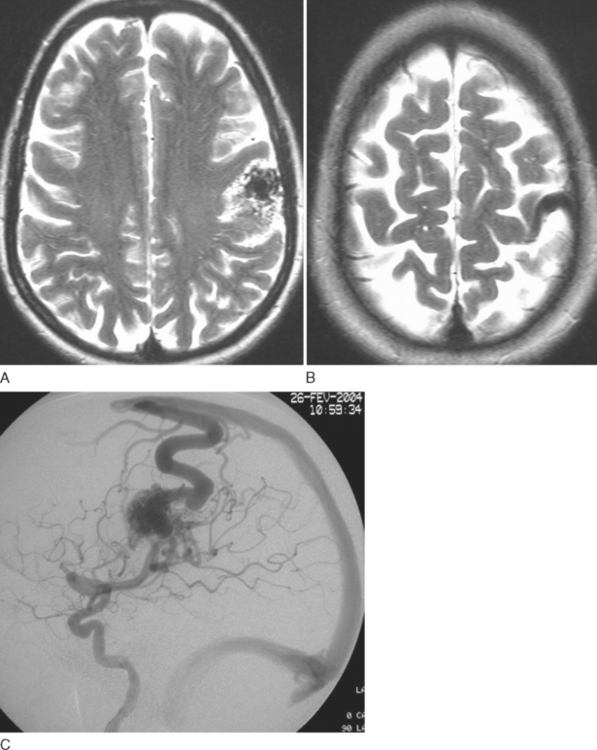

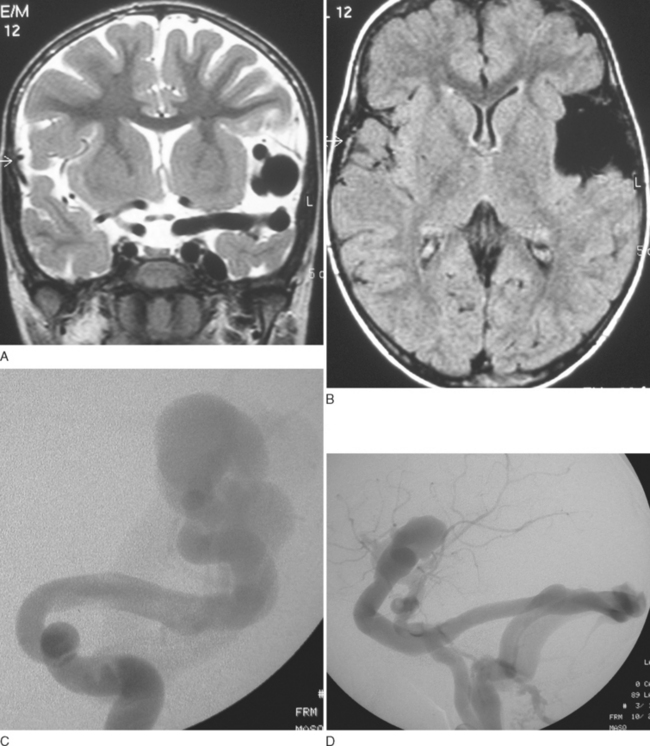

There are two broad categories of arteriovenous shunts: malformations (AVMs) and fistulae (AVFs). AVMs may be small (micro-AVMs) with one or more “normal”-sized arteries, one or more draining veins, and a nidus smaller than 1 cm in diameter. Macro-AVMs, in contrast, have arteries and veins that are larger than normal; the size of the nidus is larger than 1 cm in diameter. Compartments can be observed within lesions either during angiography or at surgery. Each compartment may have a single or multiple arterial feeders. There may be single or multiple draining veins (Fig. 44-1).

Similarly, AVFs may be of the micro or macro type. AVFs are more frequent in children and are rare in adults (Fig. 44-2).

Topography

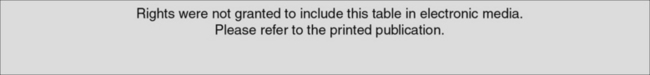

The topography of a BAVM is best assessed by combining both MRI and angiographic information. Lesions in most locations recruit predictable arterial feeders and specific draining veins (Table 44-1). The primary defect is at the capillary level. In contrast to aneurysms (arterial defective) or cavernomas (venous defective), in which associated arterial and venous anomalies are seen, respectively, the arterial tree from where the AVM feeders originate and the venous system that drains the AVM have a classic anatomical disposition.

TABLE 44-1 Topography of Intracranial Arteriovenous Lesions and Vascular Territories

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

From Berenstein A, Lasjaunias P, Ter Brugge KG: Surgical Neurorangiography, vol 2.2: Clinical and Endovascular Treatment Aspects in Adults, 2nd ed., Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2004.

Lesions at the cortex

Arteriovenous lesions exclusively involving the cortex are exclusively fed by cortical arteries and drain into superficial veins. These lesions represent sulcal AVMs, as described by Valavanis and Yasargil.5

Cortical-subcortical lesions recruit cortical arteries and drain into superficial veins but may also drain into the deep venous system if the transcerebral venous system is patent. These represent the gyral type of AVMs described by Valavanis and Yasargil.5

Multiple Brain Arteriovenous Malformations

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

HHT is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by a multisystemic vascular dysplasia and recurrent hemorrhage.6 Two gene mutations have been identified: on chromosome 9 (affecting production of endoglin; this form is known as type 1)7 and on chromosome 12 (affecting production of activin receptor-like kinase; this form is known as type 2). An uncharacterized third mutation is also suspected. These mutations lead to the formation of abnormal vessels and abnormal connections between vessels. It has to be emphasized that the target of dysfunction in HHT is not in arteries but in venules.

In the general population of patients with BAVMs, up to 2.2% of cases may be associated with HHT.8 With multiple BAVMs, however, up to 25% of cases are associated with HHT.9 Ten percent to 20% of HHT patients have cerebral involvement.10 In these patients, the cerebral vascular malformations manifest in three main phenotypes: large AVFs, small AVMs with a nidal diameter between 1 and 3 cm, and micro-AVMs with a nidal diameter smaller than 1 cm. These AVMs are often multiple and are almost exclusively located near the cortex.8,11 Although characteristic telangiectasia occur in the skin, oral mucosa, and the lips of patients with HHT, telangiectasia is not known to develop in the brain. High-flow type AVFs with venous ectasias are seen in children younger than 5 to 6 years of age; nidus-type lesions both large and small are seen in older children and in adults.1,12–14 Twenty-five percent of single AVFs in children and 50% of multifocal AVFs occur in patients with HHT.

Cerebral DSA may demonstrate multiple areas of arteriovenous shunting, always cortical in location, either supratentorial or infratentorial. In addition, high-quality cerebral DSA can demonstrate tiny lesions, particularly micro-AVMs, which may appear occult on MRI, because these lesions usually have normal-sized feeding arteries and draining veins.10

Cerebrofacial arteriovenous metameric syndromes

CAMSs,15 also called Wyburn-Mason or Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome, are associated with ipsilateral AVMs of the brain, retina, and facial regions. Their segmental expression reflects their common origin from tissues involved in cerebrofacial vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. The metameric pattern of involvement is suggestive of a disorder of the neural crest or adjacent cephalic mesoderm15 at early segmental stages of differentiation.

Unclassified multiple brain arteriovenous malformations

Several case reports have described so-called multifocal BAVMs. They seem to be twice more frequent in children than in adults. They can be randomly spread on the cortex; mirror-image deep-seated nidi have been reported. One half of multifocal AVFs in children belong to this group.1,14

Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestation, and Natural History

The clinical manifestation of BAVM may be related to the shunt itself or to secondary changes (visible on high-flow angiopathy) that occur in response to chronic shunting. It also depends on the age of the patient. Manifesting clinical features include chronic headaches, seizures, cerebral hemorrhage, and neurological deficits.

Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage in a patient with a BAVM represents a significant change in the compliance of the vascular system. Bleeding can result from rupture of the AVM nidus, arterial aneurysm rupture, or venous rupture, which may occur close to or remote from the AVM. It has been shown that arterial aneurysms are not significantly associated with hemorrhagic manifestation,5 of BAVMs. The presence of aneurysms within an AVM nidus is, however, noted to significantly worsen the natural history of future hemorrhages.16 Deep venous drainage and deep location of a BAVM are associated with a higher risk of hemorrhagic manifestation.17

Seizure and Neurological Deficit

Seizure is the second most frequent manifesting symptom in all BAVM patients and occurs in up to 53% of cases. The AVM locations most frequently associated with seizure production are the motor-sensory strip and the temporal areas, representing close to 70% of cases of BAVM with seizures. For most of the less functional brain areas, seizure manifestations may be overlooked unless secondarily generalized. Neurological deficit not associated with hemorrhage, in contrast, is an infrequent symptom, occurring in only 8% of patients over a 10-year period.18

Arterial ischemia may theoretically result from two types of mechanism: a “steal” phenomenon or occlusive changes. The concept of “steal” is based on the angiographic nonvisualization of vessels in a normal area of the brain that should have been visualized at the time of injection. However, careful angiographic evaluation always demonstrates the “missing” branches through leptomeningeal anastomoses from adjacent territories, thus expressing the adaptability of the brain’s circulation. Arterial stenosis and occlusion proximal to an AVM may range in appearance from a single vessel narrowing to a moyamoya pattern. Such changes are usually slowly progressive, allowing for stepwise compensation, including leptomeningeal angiectasia, which accounts for their clinically silent development. These changes may eventually lead to progressive symptoms such as headaches, neurological deficits, and seizures. Multivariate analysis has shown that patients with such occlusive changes and angiogenesis may have lesser hemorrhagic risk than do patients without such changes.19

Headache

Constant headaches or episodes of throbbing (“migraine-like”) headaches can occur in the same patient. The headaches are often localized to the same side as the AVM. In most cases, the exact cause of the headache remains unclear, although in some patients, there may be a relationship between the angioarchitectural features and the headaches. Dural and posterior cerebral artery supplies to a BAVM are known to be potentially responsible for headaches that tend to disappear after embolization therapy, in our experience. Conversely, embolization of middle and anterior cerebral artery supply to a parietal lobe BAVM may worsen headaches if the posterior cerebral artery supply is increased after such embolization. It does not seem that transdural supply to an AVM causes headache; such a feature is suggestive of ischemia of the underlying cortex.

Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment

The discovery of a BAVM in a patient does not represent an automatic indication for treatment. There is growing evidence in both the surgical and endovascular literature that every BAVM is unique and that different BAVMs do not carry a similar risk for future symptoms.20 The risk associated with treatment should be lesser than that of the natural history of a particular lesion. The age of the patient is also important, and the therapeutic strategy should be based on the post-therapeutic clinical benefit expected over time and the therapeutic risks associated with therapy.

Imaging Modalities

New data from advanced MRI techniques such as diffusion-weighted imaging, perfusion imaging, and functional MRI with neuronal activation have also been useful in studying abnormal brain areas near or remote from the AVM nidus. These techniques are able to show hemodynamic and neuronal adaptive phenomena in the areas involved by the AVM and in the surrounding areas of the brain. For example, reduced cerebral perfusion in the areas around the AVM related to venous congestion may be demonstrated. Functional MRI with mapping of cortical function in relation to the AVM can also be performed. This information may help the clinician correlate clinical symptoms with their anatomical and functional substrate and influence any decisions about invasive therapy.21

Specific Factors Affecting Therapeutic Decisions

Hemorrhage

The treatment strategy after presentation with hemorrhage is dependent on how well the hemorrhage is tolerated. When surgical intervention is necessary to remove an intracerebral hematoma, excision of the malformation at the same time is sometimes possible. Most hemorrhages are well tolerated,22 and no immediate AVM treatment is usually necessary. There is seldom a need for urgent treatment after BAVM hemorrhage, and a treatment strategy can be planned accordingly. Careful analysis of the angioarchitecture is important in order to look for suspicious angiographic features that are probably responsible for the hemorrhage (prenidal or intranidal aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm). These represent an indication for early treatment targeted toward obliteration of such weak points (partial targeted embolization).

Large size of a BAVM is associated with increased risk of future hemorrhage.23 Partial targeted embolization with reduction of nidal size and specific angioarchitectural features has been shown to reduce future risk of hemorrhage.24

Seizures

Seizures occur at presentation in 10% to 53% of patients with BAVMs, the majority being partial or partial complex seizures. Subsequent seizure control with antiepileptic medication is achieved in most patients; therefore, seizure control by itself rarely becomes an indication for intervention. Refractory status epilepticus is an exception that may represent an indication for endovascular treatment, and such management has been successful in bringing seizure management under control. Worsening or new onset of seizures after treatment is rare.

Age

The younger the patient is at the time of presentation, the more likely it is that active treatment should be considered. Presentation at an early age represents an early imbalance between the lesion and host. Newborns with congestive heart failure are the most dramatic examples of such an imbalance. Hydrocephalus in infants may also be secondary to cerebrospinal fluid absorption abnormalities and may result in irreversible developmental delay if endovascular treatment is not undertaken. The melting brain syndrome may also develop rapidly in some young infants if treatment is delayed.25

Patients older than 60 years at presentation are at a higher risk of bleeding,18 up to 89% by 9 years, in comparison with a 15% risk in the same period for patients aged 20 to 29. In addition, in older patients, bleeding carries very high rates of morbidity and mortality, because the older brain has less plasticity to recover. This may influence the management strategy for partial targeted therapy to restore once again the equilibrium between host and AVM.

Modes of Therapy

The role of surgery, endovascular glue embolization, stereotactic radiosurgery, and/or combined therapy in the treatment of BAVMs varies from center to center, depending on the expertise available. The location of a malformation, the size, and deep venous drainage are the most important factors in determining the risks of surgical resection of an AVM,26 whereas these features are of only minor concern in the endovascular approach. Technically, morbidity associated with embolization is related to the capacity to reach the lesion endovascularly and to remain strictly within the nidus during glue embolization. Therefore, deep lesions such as brainstem, thalamic, or basal ganglia lesions, although obviously more risky to treat, can be obliterated by careful embolization, whereas surgery in such locations would carry much higher risks.

Stereotactic radiosurgery with the gamma beam, linear accelerator, or proton beam is another accepted mode of BAVM therapy. Radiosurgery leads to progressive occlusion of BAVMs by inducing vessel wall thickening, thrombosis, and, finally, occlusion of the vessel lumen. This occurs over a period of typically 2 years. During this period of 2 years, however, it does not provide immediate protection from future hemorrhage. The efficacy of radiosurgery also depends on lesion size and volume,27–29 the success rate being lower for large lesions, which require a much higher radiation dose. Radiosurgery is therefore generally an option for nidus-type lesions that are smaller than 3 cm and are not easily accessible via endovascular or surgical means.

SPINAL CORD ARTERIOVENOUS MALFORMATIONS

Incidence

Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord are considered uncommon lesions. Their incidence, expressed as a percentage of the total number of the various types of spinal space-occupying lesions, ranges from 3%30 to 16%.31 The discrepancy is explained by the introduction of better diagnostic modalities. Nevertheless, the true incidence of spine and spinal cord vascular malformations may be underestimated.

Although cerebral vascular malformations are more common than spinal ones, the comparative incidence in relation to brain versus spinal tumors is very similar, ranging from 2% to 4%.32,33 This suggests that the frequency of SCAVMs in comparison with BAVMs is correlated with the mass or volume ratio between spinal cord and brain tissue. The prevalence of incidental or asymptomatic spinal vascular malformations is difficult to ascertain, inasmuch as the spinal cord is usually not inspected on routine autopsy.

Classification and Angioarchitecture

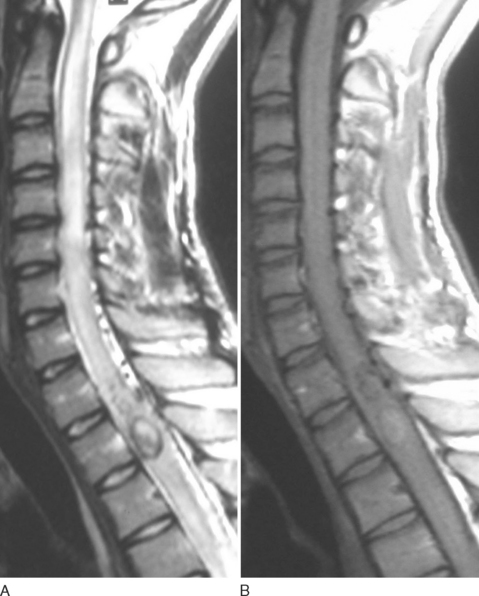

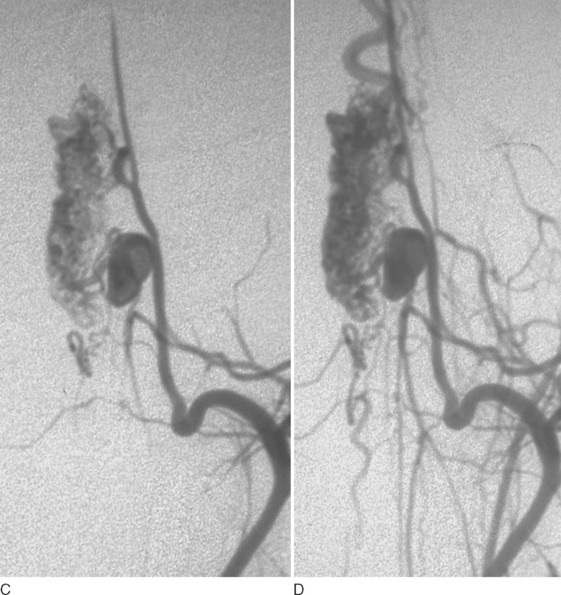

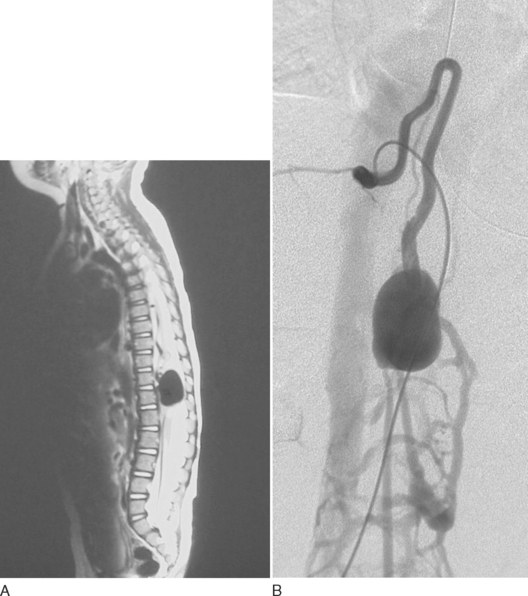

As in the brain, SCAVMs may be divided into nidal (AVMs) or fistulous types (AVFs). Nidus-type lesions are characterized by a network of abnormal channels (nidi) between the arterial feeders and the draining veins (Fig. 44-3). Fistula-type lesions, in contrast, consist of a direct communication or opening between a feeding artery and a draining vein (Fig. 44-4). Large nidus-type lesions are usually embedded within the spinal cord, whereas small lesions are often more superficial, near the surface of the cord. Fistula-type lesions, which may also be distinguished as large (macro-AVFs) and small (micro-AVFs), are always found on the surface of the spinal cord (extramedullary).

SCAVMs may be classified into three main groups (Table 44-2), described as follows.34

TABLE 44-2 Classification of Spinal Cord Arteriovenous Malformations

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

Rodesch G, Hurth M, Alvarez H, et al: Classification of spinal cord arteriovenous shunts: proposal for a reappraisal—the Bicêtre experience with 155 consecutive patients treated between 1981 and 1999. Neurosurgery 2002; 51:374-380.

Genetic Hereditary Lesions

This first group of SCAVMs is caused by a genetic hereditary disorder, in which vascular germinal cells are affected by disease. The main syndrome in which genetic links can be recognized is HHT (see section on BAVMs). SCAVMs associated with HHT are almost always single macro-AVFs, particularly in the pediatric population. Indeed, macro-AVFs may be the first expression of the disease in children; the discovery of a spinal cord macro-AVF should therefore raise the possibility of this underlying genetic hereditary disease.13,35 These lesions are usually single at the cord but can be associated to intracranial ones.36

Genetic Nonhereditary Lesions

This second group of SCAVMs is not related to a hereditary disorder; it includes multifocal lesions potentially sharing metameric links (see also section on BAVMs).37

Each segment in the spine involves the spinal cord (corresponding myelomere); nerve root; bone; and paraspinal, subcutaneous, and skin tissues. A patient may therefore present with multiple shunts, which involve several different myelomeres (segments) of the spinal cord (multimyelomeric SCAVMs) both on the cord and on intradural nerve roots. The association of a SCAVM with a nerve root AVM in the same patient is metameric if the spinal cord segment (myelomere) involved corresponds to that of the nerve involved.

Klippel-Trénaunay and Parkes-Weber syndromes are characterized by cutaneous capillary hemangiomas or port wine stains, varicosities and lymphedema, and bone and soft tissue hypertrophy of the affected extremity, usually the lower limb. Parkes-Weber syndrome is also associated with the presence of AVMs in the involved extremity. Associated SCAVMs are known to occur in these syndromes.34,38 In such cases, the SCAVMs are usually multiple, and a metameric disposition is suspected but cannot be definitely demonstrated.

Other multifocal spinal cord lesions have been described without metameric linkage.

Clinical Presentation

In SCAVM series that include adults and children, the mean age of presentation is in the mid-20s.39–41 However, in close to 20% of cases, the lesion is diagnosed in children younger than 16 years of age.42 In a more recent series,43 30% were children.

Spinal Hemorrhage

The most striking symptom in the clinical presentation of SCAVMs is the high incidence of hemorrhage, which may be either subarachnoid or within the spinal cord itself (hematomyelia) and occurs in 50% of all SCAVM patients. Hemorrhage, particularly hematomyelia, is associated with the onset of new, significant, and often devastating neurological deficits or with aggravating preexisting deficits. Hemorrhage is seen more frequently in cervical lesions than in thoracic and lumbar lesions.39–41 Hemorrhage is also more common in children.43

Nonhemorrhagic Symptoms

Muscle atrophy and sensory disturbances that may result in multiple injuries can be observed in patients with SCAVMs. Spinal deformities such as kyphosis and scoliosis are also seen. In addition, complications common to other types of spinal cord dysfunction, such as urinary tract infections, respiratory infections, and decubitus ulcerations, may also be present and must be taken into consideration in determining the morbidity and final outcome of these patients.

Diagnosis and Clinical Assessment

Noninvasive Imaging Techniques

MRI remains limited in its ability to accurately locate the site of arteriovenous communication and the evaluation of the angioarchitecture of an AVM. Pitfalls of this technique in the assessment of patients with vascular lesions of the spinal cord are related primarily to cerebrospinal fluid pulsation artifacts that may produce images highly suggestive of spinal cord vascular lesions.44 This is of particular importance in pediatric patients, in whom such artifacts may lead to unnecessary angiographic exploration.

If, however, the study findings are negative or inconclusive and if the diagnosis is compatible with venous congestion from a small arteriovenous shunt draining into the ventral spinal cord vein, spinal DSA should be performed.45 For treatment planning, spinal DSA still remains the study of choice.

Treatment and Management

Endovascular Embolization and Surgery

In patients with a fixed deficit or severe clinical signs of cord transection, treatment is of unlikely functional benefit. Nonetheless, treatment is indicated, especially in cases of repeated hemorrhage and in high cord lesions, to reduce the risk of repeated life-threatening spinal hemorrhage. In some patients with severe pain related to compressive symptoms, palliative embolization may also be beneficial.

CONCLUSION

Berenstein A, Lasjaunias P, Ter Brugge KG. Surgical Neurorangiography, vol 2.2: Clinical and Endovascular Treatment Aspects in Adults, 2nd ed., Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2004:609-735. 760–847.

Hofmeister C, Stapf C, Hartmann A, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and morphological characteristics of 1289 patients with cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Stroke. 2000;31:1307-1310.

Lasjaunias P. Vascular Diseases in Neonates, Infants and Children: Interventional Neuroradiology Management. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1997;203-319.

Mansmann U, Meisel J, Brock M, et al. Factors associated with intracranial hemorrhage in cases of cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:272-281.

Meisel HJ, Mansmann U, Alvarez H, et al. Cerebral arteriovenous malformation and associated aneurysms: analysis of 305 cases from a series of 662 patients. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:793-802.

Rodesch G, Hurth M, Alvarez H, et al. Angioarchitecture of spinal cord arteriovenous shunts at presentation. Clinical correlations in adults and children: the Bicêtre experience on 155 consecutive patients seen between 1981–1999. Acta Neurochir. 2004;146:217-227.

Stefani MA, Porter PJ, Ter Brugge KG, et al. Angioarchitectural factors present in brain arteriovenous malformations associated with hemorrhagic presentation. Stroke. 2002;33:920-924.

Valavanis A, Yasargil MG. The endovascular treatment of brain arteriovenous malformations. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 1998;24:131-214.

1 Weon YC, Yoshida Y, Sachet M, et al. Supratentorial cerebral arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) in children: review of 41 cases with 63 non choroidal single-hole AVFs. Acta Neurochir. 2005;147:17-31.

2 Garretson HD. Intraranial arteriovenous malformations. In: Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS, editors. Neurosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1985:1448-1457.

3 Jellinger K. Vascular malformations of the central nervous system: a morphological overview. Neurosurg Rev. 1986;9:177-216.

4 Mohr JP. Neurological manifestations and factors related to therapeutic decisions. In: Wilson CB, Stein BM, editors. Intracranial Arteriovenous Malformations. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1984:12-23.

5 Valavanis A, Yasargil MG. The endovascular treatment of brain arteriovenous malformations. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 1998;24:131-214.

6 Guttmacher AE, Marchuk DA, White RIJ. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:918-924.

7 McAllister KA, Grogg KM, Johnson DW. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat Genet. 1994;8:345-351.

8 Mahadevan J, Ozanne A, Yoshida Y, et al. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia cerebrospinal localization in adults and children: review of 39 cases. Interv Neuroradiol. 2004;10:27-35.

9 Willinsky RA, Lasjaunias P, Ter Brugge KG, et al. Multiple cerebral arteriovenous malformations: review of our experience from 203 patients with cerebral vascular lesions. Neuroradiology. 1990;32:207-210.

10 Fullbright RK, Chaloupka JC, Putman CM, et al. MR of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: prevalence and spectrum of cerebrovascular malformations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:477-484.

11 Matsubara S, Mandzia JL, Ter Brugge KG, et al. Angiographic and clinical characteristics of patients with cerebral arteriovenous malformations associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1016-1020.

12 Krings T, Ozanne A, Chng SM, et al. Neurovascular phenotypes in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia patients according to age: review of 50 consecutive patients aged 1 day–60 years. Neuroradiology. 2005;47:711-720.

13 Garcia-Monaco R, Taylor W, Rodesch G, et al. Pial arteriovenous fistula in children as presenting manifestation of Rendu-Osler-Weber disease. Neuroradiology. 1995;37:60-64.

14 Yoshida Y, Weon YC, Sachet M, et al. Posterior cranial fossa single-hole arteriovenous fistulae in children: 14 consecutive cases. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:474-481.

15 Bhattacharya J, Luo CB, Suh DC, et al. Wyburn-Mason or Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc as cerebrofacial arteriovenous metameric syndromes (CAMS): a new concept and a new classification. Interv Neuroradiol. 2001;7:5-17.

16 Meisel HJ, Mansmann U, Alvarez H, et al. Cerebral arteriovenous malformation and associated aneurysms: analysis of 305 cases from a series of 662 patients. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:793-802.

17 Stefani MA, Porter PJ, Ter Brugge KG, et al. Angioarchitectural factors present in brain arteriovenous malformations associated with hemorrhagic presentation. Stroke. 2002;33:920-924.

18 Crawford PM, West CR, Chadwick DW, et al. Arteriovenous malformations of the brain: natural history in unoperated patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:1-10.

19 Mansmann U, Meisel J, Brock M, et al. Factors associated with intracranial hemorrhage in cases of cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:272-281.

20 Hofmeister C, Stapf C, Hartmann A, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and morphological characteristics of 1289 patients with cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Stroke. 2000;31:1307-1310.

21 Ducreux D, Desal H, Bittoun J, et al. Diffusion, perfusion and activation functional MRI studies of brain arteriovenous malformations. J Neuroradiol. 2004;31:25-34.

22 Berenstein A, Lasjaunias P, Ter Brugge KG. Goals and objectives in the management of brain arteriovenous malformations. In Surgical Neurorangiography, vol 2.2: Clinical and Endovascular Treatment Aspects in Adults, 2nd ed., Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2004:703.

23 Stefani MA, Porter PJ, Ter Brugge KG, et al. Large and deep brain arteriovenous malformations are associated with risk of future hemorrhage. Stroke. 2002;33:1220-1224.

24 Meisel HJ, Mansmann U, Alvarez H, et al. Effect of partial targeted NBCA embolization in brain AVM. Acta Neurochir. 2002;144:879-888.

25 Lasjaunias P. Vascular Diseases in Neonates, Infants and Children: Interventional Neuroradiology Management. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1997;41.

26 Spetzler RF, Martin NA. A proposed grading system for arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:476-483.

27 Karlsson B, Lindquist C, Steiner L. Prediction of obliteration after gamma knife surgery for cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:425-431.

28 Pollock B, Flickinger J, Lunsford D, et al. Factors associated with successful arteriovenous malformation radiosurgery. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:1239-1247.

29 Schlienger M, Atlan D, Lefkopoulos D, et al. Linac radiosurgery for cerebral arteriovenous malformations: results in 169 patients. Int J Radiation Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:1135-1142.

30 Wyburn-Mason R. The Vascular Abnormalities and Tumours of the Spinal Cord and Its Membranes. London: H. Kimpton, 1943.

31 Pia HW, Vogelsang H. Diagnose und Therapie spinaler Angiome [Diagnosis and therapy of spinal angioma]. Dtsch Z Nervenheilkd. 1965;187:74-96.

32 Olivecrona H. The cerebellar angioreticulomas. J Neurosurg. 1957;9:317-330.

33 Krenchel NJ. Intracranial Racemose Angiomas: a Clinical Study. Copenhagen: Universitetsforlaget i Aarhus, 1961.

34 Rodesch G, Hurth M, Alvarez H, et al. Classification of spinal cord arteriovenous shunts: proposal for a reappraisal—the Bicêtre experience with 155 consecutive patients treated between 1981 and 1999. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:374-380.

35 Mandzia JL, Ter Brugge K, Faughnan ME, et al. Spinal cord arteriovenous malformations in two patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Childs Nerv Syst. 1999;15:80-83.

36 Mazighi M, Porter P, Alvarez H, et al. Associated cerebral and spinal AVM in infant and adult: report of two cases treated by endovascular approach. Intervent Neuroradiol. 2000;6:321-326.

37 Matsumaru Y, Pongpech S, Laothamas J, et al. Multifocal and metameric spinal cord arteriovenous malformations: review of 19 cases. Interv Neuroradiol. 1999;5:27-34.

38 Nimii Y, Ito U, Tone O, et al. Multiple spinal perimedullary arteriovenous fistulae associated with the Parkes-Weber syndrome. Interv Neuroradiol. 1998;4:151-157.

39 Djindjian M, Djindjian R, Hurth M, et al. Spinal cord arteriovenous malformations and the Klippel-Trénaunay-Weber syndrome. Surg Neurol. 1977;8:229-237.

40 Rosenblum B, Oldfield EH, Doppman JL, et al. Spinal arteriovenous malformations: a comparison of dural arteriovenous fistulae and intradural AVM’s in 81 patients. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:795-802.

41 Berenstein A, Lasjaunias P. Surgical Neuroangiography. vol 4. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1992:197-251.

42 Yasargil MG, Symon L, Teddy PG. Arteriovenous malformations of the spinal cord. Symon L, editor. Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery. vol 11. Vienna: Springer-Verlag; 1984:61-102.

43 Rodesch G, Hurth M, Alvarez H, et al. Angioarchitecture of spinal cord arteriovenous shunts at presentation: clinical correlations in adults and children. The Bicêtre experience on 155 consecutive patients seen between 1981–1999. Acta Neurochir. 2004;146:217-227.

44 Levy LM, di Chiro G, Brooks RA, et al. Spinal cord artifacts from truncation errors during MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;166:479-483.

45 Lasjaunias P, Berenstein A, Terbrugge KG. Spine and spinal cord arteries and veins. In Surgical Neuroangiography, vol 1: Clinical Vascular Anatomy and Variations, 2nd ed., Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2001:73-164.