Chapter 11 Arterial puncture site closure and aftercare

Correct management of the access site following percutaneous intervention reduces complications and facilitates early mobilisation and discharge.

Correct management of the access site following percutaneous intervention reduces complications and facilitates early mobilisation and discharge. A variety of techniques and devices have been developed to aid sheath removal and haemostasis for cases that are performed by femoral route.

A variety of techniques and devices have been developed to aid sheath removal and haemostasis for cases that are performed by femoral route.INTRODUCTION

It is often said that restenosis is the ‘Achilles heel’ of percutaneous intervention. With this threat now rapidly receding thanks to drug-eluting stents (see Chapter 13) it is time for the arterial puncture site to step forward as the rightful owner of this classical metaphor.

This ease of use comes at a price, however, complications relating to the femoral artery occur in up to 9% of cases, and very rarely may be fatal.1 A full working knowledge of the correct procedure for sheath removal and groin site aftercare is, therefore, essential for operators using this route.

As with all invasive medical procedures, the complication rate from femoral access can be minimised by careful case selection: increased complications are seen in patients with peripheral vascular disease, advanced age, repeat procedures and aggressive anti-thrombotic regimens.2 Similarly increased operator experience reduces complication rates. Further to this, complications can be limited by selection of the smallest diameter sheath that will allow effective coronary intervention. Downsizing from 8 French is associated with reduced adverse events.3

Complications relating to the femoral access site can be haemorrhagic (haematoma, pseudo-aneurism and retroperitoneal bleeding), related to compression from haematomas, embolic or infective. These complications are covered in detail in Chapter 12 (Complications of PCI).

SHEATH REMOVAL

Mechanical pressure devices

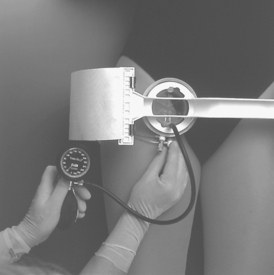

This device has a transparent inflatable pressure element fitted to a rigid beam, which in turn is strapped to the patients lower torso. The inflatable element allows the degree of pressure to be varied, and visualisation of the compression and puncture sites (Fig. 11.1).

There are conflicting reports as to whether this device reduces complications when compared to manual compression,4,5 and some evidence that there may be some increased discomfort when compared to the use of a vascular closure device.6 It is, therefore, important to ensure adequate patient preparation prior to siting a FemoStop (adequate hydration, analgesia and possibly sedation).

Arterial closure devices

Arterial closure devices have been developed as an alternative to manual pressure or external pressure devices in an attempt to reduce haemostasis times, enhance early mobilisation and reduce discomfort for the patient and staff. Early hopes that direct arterial closure would reduce complications and, therefore, lead to safer treatment of the groin site have been largely unsubstantiated, however.7,8

One recent meta-analysis of closure device use has suggested that there is no specific advantage or increased risk in using arterial closure devices vs. manual compression in diagnostic cases, but when applied to interventional cases the same was true for Angioseal and Perclose devices, but not Vasoseal. This latter device appeared to have a disadvantage when compared to mechanical compression in the PCI group.8 A further meta-analysis failed to show conclusively that arterial closure devices are superior to manual compression both in terms of safety and effectiveness.

Angioseal

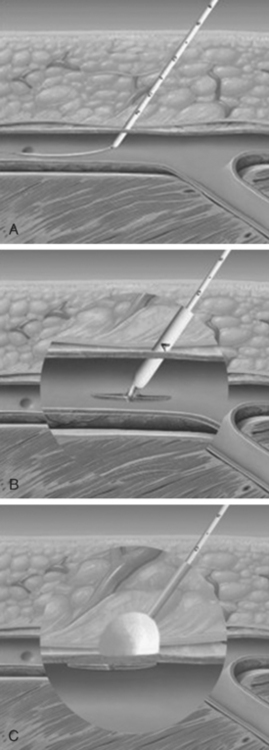

The femoral sheath is replaced over a guidewire with a specific introducer sheath (Fig. 11.2a). Therafter the anchor/collagen introducer is passed into the sheath (Fig. 11.2b) and deployed (Fig. 11.2c) leaving the ‘foot’ adjacent to the endoluminal surface and the collagen pressed on the external surface of the artery.

Perclose

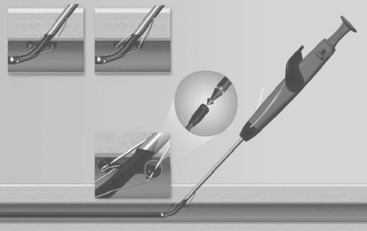

The Perclose device is a semi-automated suture device. This device does not require a thrombin or collagen plug and thereby leaves no foreign material in the lumen. The device is advanced into the femoral artery and the correct depth is signalled by a flush back of blood. Following this a suture ‘foot’ is deployed into the artery and the sutures advanced and tightened. The excess suture material is then trimmed off with a specific device (Fig. 11.3).

Vasoseal

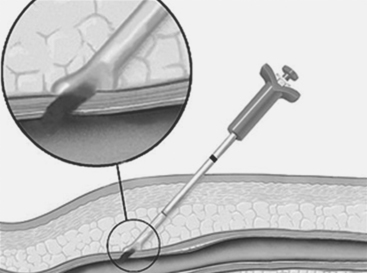

This system does not require an intra-arterial component.

Briefly, a specific arterial locator is passed through the intra-arterial sheath and the sheath removed. A J segment within the artery allows accurate positioning of first a dilator sheath and then the collagen deployment catheter which is used to place the collagen plug on the external surface of the artery (Fig. 11.4).

1 Nasser T, Mohler ER3rd, Wilensky RL, et al. Peripheral vascular complications following coronary interventional procedures. Clin Cardiol. 1995;18:609-614.

2 Resnic F, Blake GJ, Ohno-Machado L, et al. Vascular closure devices and the risk of vascular complications after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients receiving glycoprotein IIbIIIa inhibitors. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:493-496.

3 Muller DW, Shamir KJ, Ellis SG, et al. Peripheral vascular complications after conventional and complex percutaneous coronary interventional procedures. Am J Cardiol. 1992 Jan 1;69(1):63-68.

4 Sridhar K, Fischman D, Goldberg S, et al. Peripheral vascular complications after intracoronary stent placement: prevention by use of a pneumatic vascular compression device. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1996 Nov;39(3):224-229.

5 Benson LM, Wunderly D, Perry B, et al. Determining best practice: comparison of three methods of femoral sheath removal after cardiac interventional procedures. Heart Lung. 2005 Mar-Apr;34(2):115-121.

6 Juergens CP, Leung DJ, Crozier JA, et al. Patient tolerance and resource utilization associated with an arterial closure versus an external compression device after percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004 Oct;63(2):166-170.

7 Koreny M, Riedmuller E, Nikfardjam M et al. Arterial puncture site closing devices compared with standard manual compression after cardiac catheterisation. JAMA; 291:350–7.

8 Nikolsky E, Mehran R, Halkin A, et al. Vascular complications associated with arteriotomy closure devices in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary procedures — a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1200-1209.