8 Artefill®

a third-generation polymethylmethacrylate in collagen soft tissue filler

Summary and Key Features

• Artefill® is the newest generation polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) filler

• Artefill® consists of PMMA microspheres suspended in bovine collagen

• The PMMA microspheres of Artefill® are more uniform in size than the earlier generation PMMA fillers and there are very few particles less than 20 µm, thereby preventing phagocytosis and subsequent granuloma formation

• Artefill® is best for deeper creases and folds rather than fine lines

• In the USA, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indication is for nasolabial folds

• Artefill® lasts at least 5 years and may be permanent in some patients

• Placement should be in the deep dermis or at the dermal–subcutaneous junction

• Skin testing to the bovine collagen component of the filler should be performed at least 1 month prior to treatment with Artefill®

• Although rare, granuloma formation may occur years after injection of Artefill®

• Different types of anesthesia may be used prior to Artefill® placement

Introduction

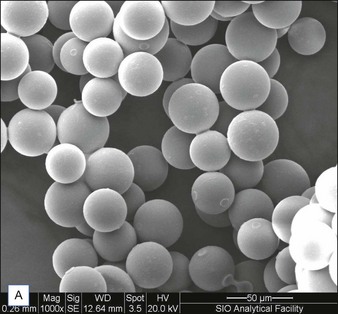

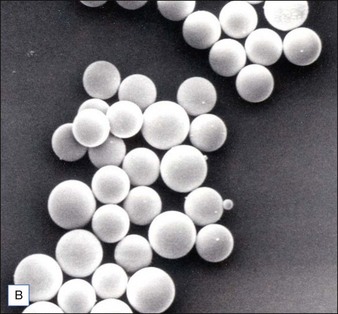

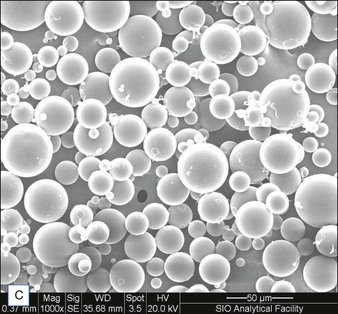

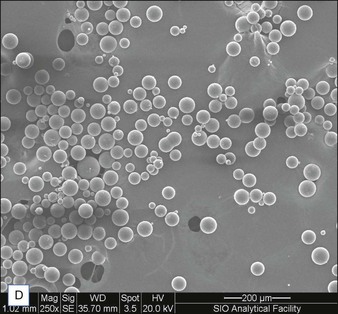

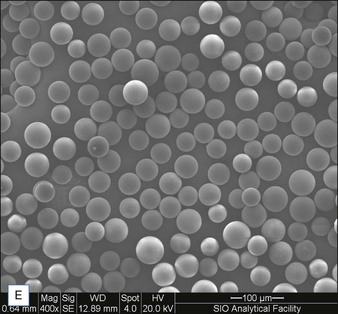

Biological dermal fillers reliably and safely augment facial wrinkles and folds, but necessitate repeat treatments after they have been resorbed, generally within a 12-month period. Artefill®, a novel permanent implant, was developed to overcome this limitation. This soft tissue filler is composed of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) microspheres suspended in a collagen gel matrix containing 0.3% lidocaine. It is a third-generation PMMA-based filler product that contains an optimized collagen matrix with PMMA microspheres that have enhanced uniformity and consistency as well as near elimination of nanoparticles. It is critical to distinguish Artefill® from prior generation PMMA products (Artecoll® and Arteplast®). Not all PMMA products are the same and scanning electron microscopy can show a wide variation of nanoparticles, sphere irregularities, and sphere shapes and sizes (Fig. 8.1), all of which might contribute to early or late adverse events.

Patient selection / treatment areas

Some of the other potential off-label indications for Artefill® are in the permanent treatment of selected primary and secondary nasal deformities and for dorsal nasal augmentation (Fig. 8.2). Permanent reconstruction of lateral chin contour abnormalities following genioplasty, small depression defects about the head and neck, permanent nipple augmentation and acne scar injection are other off-label indications that might benefit from Artefill®.

Patient evaluation and injection technique

Injection of Artefill® into the nasolabial fold is generally very straightforward. It is important to be in the proper depth, which is the deep dermis (Fig. 8.3). Artefill® is injected using a 26- or 27-gauge, 5/8-inch (16 mm) needle. It is critical that the needle be placed at the correct depth. If the silver of the needle is seen through the skin, do not inject as a ridge or lump could easily occur. When the needle is placed too deep, the material will be largely deposited in the fat. When injecting into the correct deep dermal plane, the needle should slightly tent the overlying skin (see Fig. 8.3). Injection should be stopped prior to the needle being removed from the skin to avoid leaving a small bump. If this were to occur, it is important to immediately drain the material in a retrograde fashion through a needle puncture. Generally, using a gloved fingernail, the material is easily expressed through the puncture hole. Ideally, injection is carried out using a linear threading technique as the needle is withdrawn. Radial or fanning injections are most effective in the corners of the mouth, the marionette lines, and in the wedge-shaped depression just below and lateral to the alar attachment. As one gains more experience with the material, injection can be done in a pushing fashion. In some specialized areas such as the nose, microdroplets can be placed and then massaged into shape. As one gains more confidence with the material, serial injections will be less necessary, but when starting out it is best to inform patients that optimum filling should be performed over two or three sessions.

Clinical trials

Summary of 5-year follow-up safety and efficacy study

Ratings of success and satisfaction

In addition to assessing the degree of nasolabial fold correction using the FFA scale, other methods were used to evaluate cosmetic correction. A five-point ordinal scale was used by the investigators to rate the success of treatment with the novel PMMA filler, ranging from ‘Not at all successful’ to ‘Completely successful’. Likewise, subjects rated their satisfaction with the PMMA filler according to a similar five-point scale ranging from ‘Very dissatisfied’ to ‘Very satisfied’ (Box 8.1).

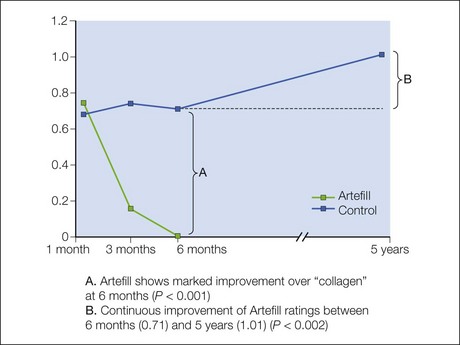

Masked observer facial fold assessment ratings of efficacy at 5 years compared with baseline

The PMMA filler maintained significant cosmetic correction in nasolabial folds at 5 years after subjects’ last treatment compared with baseline (n = 119). Five of the 124 nasolabial fold subjects were excluded from this analysis because they did not have either baseline or 5-year photographs. Figure 8.4 shows an improvement of 1.01 points in masked observer FFA rating for this time period (P < 0.001, paired t-test); as the FFA is a 0–5 scale, a change of 1 point represents a substantial improvement in cosmetic effect. Actual results are illustrated in photographs of a male (Fig. 8.5) and female (Fig. 8.6) patient. Before treatment (baseline), the male patient exhibited a pronounced nasolabial fold, which was dramatically improved by 6 months following the injection of a total volume of 4 mL of PMMA filler per nasolabial fold over three injection sessions. The improvement was maintained and even continued to develop at 12 months and 5 years. The female patient received 1.2 mL of PMMA filler per nasolabial fold. The inter-rater agreement for nasolabial folds was found to be high (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.845).

Figure 8.5 Male patient – baseline (pre-treatment) to year 5.

From Cohen SR, Berner CF, Busso M, et al 2006 Artefill®: A long-lasting injectable wrinkle filler material – summary of the US Food and Drug Administration trials and a progress report on 4- to 5-year outcomes. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 118:64S-76S

Figure 8.6 Female patient – baseline (pre-treatment) to year 5.

From Cohen SR, Berner CF, Busso M, et al 2006 Artefill®: A long-lasting injectable wrinkle filler material – summary of the US Food and Drug Administration trials and a progress report on 4- to 5-year outcomes. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 118:64S-76S.

Efficacy at 5 years compared with efficacy at 6 months

The PMMA filler not only maintained nasolabial fold augmentation between baseline and 5 years, but masked observer FFA ratings also improved by an average of 0.20 points for the time period between 6 months and 5 years (see Fig. 8.4, item B), indicating that the cosmetic effect improved gradually but significantly (P = 0.002, n = 113, paired t-test). This is evident in the patient photographs, particularly when comparing the 1-year and 5-year timepoints (see Figs 8.5 and 8.6). In a paired analysis of the group of crossover patients (n = 45), the PMMA filler-induced improvement assessed 5 years after treatment with this novel filler (0.91 points) was significantly greater than the collagen-induced improvement measured at 6 months (0.01 points) as rated by masked observer FFA (P < 0.001, paired t-test).

Safety review

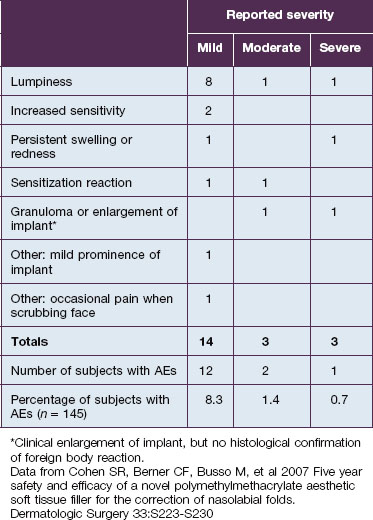

In this study, 145 subjects were evaluated for safety; 28 total adverse events were experienced by 21 subjects; and the 20 treatment-related events were distributed among 15 subjects (Table 8.1). Mild treatment-related events occurred in 8.3% of the total population; moderate events were reported in 1.4%; and severe related events in 0.7%. The most common treatment-related adverse event was lumpiness, 80% of which was deemed mild in severity.

Anderson RK, Stagg A, Piacquadio D 2008 Comparison of commercially available polymethylmethycralate (PMMA) based soft tissue fillers. American Academy of Dermatology meeting (Poster presentation)

Cohen SR, Holmes RE. Artecoll: a long-lasting injectable wrinkle filler material: report of a controlled, randomized, multicenter clinical trial of 251 subjects. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;114:964–979.

Cohen SR, Berner CF, Busso M, et al. Artefill: a long-lasting injectable wrinkle filler material – summary of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration trials and a progress report on 4- to 5-year outcomes. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;118(3 suppl):64S–76S.

Cohen SR, Berner CF, Busso M, et al. Five year safety and efficacy of a novel polymethylmethacrylate aesthetic soft tissue filler for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:S223–S230.

Gelfer A, Carruthers A, Carruthers J, et al. The natural history of polymethylmethacrylate microsphere granulomas. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:614–620.

Judet J. Protheses en resins acrylic. Mémoires. Académie de Chirurgie. 1947;73:561.

Klemm KW. Gentamicin-PMMA chains (Septopal chains) for local antibiotic treatment of chronic osteomyelitis. Reconstruction Surgery and Traumatology. 1988;20:11.

Laeschke K. Biocompatibility of microparticles into soft tissue fillers. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2004;23(4):214–217.

Lemperle G, Ott H, Charrier U, et al. PMMA microspheres for intradermal implantation. Part I. Animal research. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 1991;26:57.

Lemperle G, Holmes RE, Cohen SR, et al. A classification of facial wrinkles. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2001;108(6):1735–1750.

McClelland M, Egbert B, Hanko V, et al. Evaluation of Artecoll polymethylmethacrylate implant for soft tissue augmentation: biocompatibility and chemical characterization. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1997;100:1466.

Morhenn VB, Lemperle G, Gallo RL. Phagocytosis of different particulate dermal filler substances by human macrophages and skin cells. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28:484.