7. Arnold-Chiari Malformation

Definition

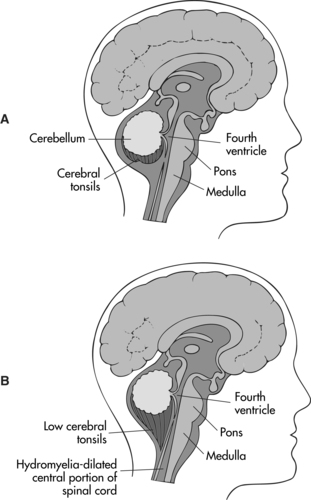

Arnold-Chiari malformation is a complex congenital malformation of the hindbrain that is often associated with myelomeningocele. The deformity is characterized by downward displacement of the medulla, fourth ventricle, and cerebellum into the spinal canal. The pons and fourth ventricle are elongated, which is believed to be the result of the relatively small posterior fossa. It is the most common, serious malformation of the posterior fossa. Arnold-Chiari is also known as Chiari II malformation (CM II).

Incidence

Recent estimates are that the frequency of this malformation in the United States is approximately 1:1000.

Etiology

This congenital anomaly is a complex entity that involves the skull, dura, brain, spine, and spinal cord. The association with myelomeningocele is almost 100%. Several theories have been advocated to explain the development of the Arnold-Chiari malformation.

The various theories can be classed into two schools of thought. The first ascribes the malformation to mechanical factors, and the second finds the cause to be abnormal embryologic development. The “mechanical forces school” uses theories of hydrodynamics and traction. The “embryologic school” includes theories on developmental arrest, primary dysgenesis, small posterior fossa, hindbrain overgrowth, neuroschisis, and neurulation abnormalities. One of the simpler and widely accepted theories suggests that the condition arises when a cerebellum of normal size or proportion develops in a posterior fossa that is abnormally small with a low tentorial attachment.

|

| Arnold-Chiari Malformation. Comparison of (A) normal brain and (B) Arnold-Chiari type II malformation. |

Signs and Symptoms

Infancy

• Aspiration

• Bladder and/or bowel function degradation

• Depressed/absent gag reflex

• Episodic apnea

• Fixed retrocollis

• Impaired swallowing

• Nystagmus

• Respiratory distress

• Scoliosis

• Upper and lower extremities pain

• Weak/absent cry

Childhood

• Appendicular and/or truncal ataxia

• Depressed/absent cough reflex

• Exaggerated deep tendon reflexes

• Gastroesophageal reflux

• Gradual function loss

• Mirror movements

• Nystagmus (horizontal and rotatory)

• Recurrent pneumonia secondary to aspiration

• Spastic quadriparesis

• Syncopal episodes

• Upper extremity weakness with increased tone

Medical Management

Medical management of the patient with Arnold-Chiari malformation primarily involves surgical interventions. Hydrocephalus develops in about 80% of patients with Arnold-Chiari malformation, and they often present as a medical emergency in need of insertion of a shunt for relief of the intracranial pressure. In addition to hydrocephalus, the patient may have several associated abnormalities and may require general anesthesia to facilitate the corrective surgical intervention(s).

Complications

• Brainstem dysfunction

• Cranial nerve dysfunction

• Mortality: 10% to 15% in the first 2 years; some report long-term rates of up to 50%

• Respiratory difficulties (apnea, inspiratory stridor, prolonged expiratory apnea with cyanosis [PEAC])

Anomalies Associated with Arnold-Chiari Malformation

• Aqueductal stenosis

• Contracted narrow gyria

• Corpus callosium dysgenesis

• Diastematomyelia

• Heterotopias

• Low-lying, often-tethered conus medullaris below the L 2 nerve

• Malrotation of C 1 and C 2 arches

• Myelomeningocele

• Obstructive hydrocephalus

• Segmented anomalies/incomplete C 1 arch

• Septum pellucidum absence

• Syringohydromyelia

Rare Anomalies

• Cervical myelocystocele

• Frontometaphyseal dysplasia

• Holoprosencephaly

• Juvenile distal spinal muscular dystrophy

• Williams syndrome (see p. 351)

Anesthesia Implications

The associated myelomeningocele is generally surgically corrected within the first hours of the neonate’s life. This intervention frequently employs local anesthetic infiltration or general anesthesia. The primary objective is to close the defect to minimize the potential for central nervous system infection. Awake intubation of the neonate while in the lateral decubitus position is elected to avoid compression of the meningocele sac. The neonate may be placed in the supine position, so long as the meningocele sac is “insulated” from direct pressure by elevating the child’s body with a foam ring, or “doughnut.” Anesthesia can be maintained with volatile inhalational agents with mechanical ventilation. Functional neural elements have to be assessed by the surgeon; therefore, long-acting muscle relaxants should not be used. The patient is maintained in the prone position postoperatively. If the patient is extubated, respiratory status should be assessed constantly. The patient with Arnold-Chiari malformation has abnormal responses to hypoxia and hypercarbia and is also at increased risk for aspiration because of higher incidences of gastroesophageal reflux and abnormal vocal cord mobility. Finally, the patient with a myelomeningocele has a substantially higher incidence of latex sensitivity and/or true allergy; therefore it is prudent to take latex precautions.

The most common surgical intervention for the patient with Arnold-Chiari malformation is exploration of the posterior fossa. Other surgical interventions employed include suboccipital craniectomy, C 1/C 2 laminectomy, subarachnoid adhesions lysis, dural band incision, and duraplasty. Preoperatively, the patient’s neural function must be assessed with particular attention to upper airway control, protection from aspiration, and gas exchange. The appearance or exacerbation of neural symptoms during neck flexion and extension must be determined. The patient must also be assessed for the presence or absence of increased intracranial pressure (ICP).

The neck should be placed in an anatomic alignment as neutral as possible, and great care should be taken to avoid extremes in flexion or extension to avoid potential compression of neural structures. Increased ICP is always a potential development even with a shunt in place, and the anesthesia should be administered with this in mind. Mild hyperventilation to reduce the Paco 2 will help thwart the development of increased ICP. The anesthetist must also be prepared for potentially large volumes of blood loss if the transverse and/or torcular sinuses should be violated. When the patient is in the semi-sitting or prone positions, air embolism is a very real threat.