Chapter 92 Are Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries Preventable?

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is the most commonly injured ligament in the body. Disruption of the ACL is particularly common in athletic populations and among military personnel. There may be as many as 200,000 ACL injuries occurring in the United States each year. ACL deficiency leading to instability is associated with secondary meniscal and articular cartilage injury increasing the risk for gonarthrosis. ACL reconstruction is commonly performed to restore stability to the knee. It is estimated that more than 100,000 ACL reconstructions are performed annually in the United States, costing in excess of $2 billion.

Female individuals are two to six times more likely to injure the ACL compared with male individuals playing identical sports at similar levels. ACL reconstructions are performed most commonly in high-school- and college-aged individuals; however, ACL reconstruction in this active age group compared with older individuals is twice as common for female than male individuals, further supporting the findings of others that female individuals are at increased risk for ACL injury.1

Given the increasing incidence of ACL injury, together with the costly surgery to restore stability and lengthy rehabilitation involved to recover, this is an apt condition for both primary and tertiary preventive measures.2 Primary prevention aims to reduce the incidence of ACL tears, whereas tertiary prevention targets a reduction in complications from the injury such as secondary injury of the knee or subsequent graft failure. Most of the research in this area has focused on primary prevention. Sex differences in lower extremity kinematics and neuromuscular control are some of the biomechanical factors that may contribute to increased risk for ACL injury in female individuals. In fact, differences in lower extremity kinematics have been shown in female individuals while just walking compared with age- and activity-level–matched male individuals.3

OPTIONS

The Henning Program was one of the first training interventions described for the prevention of ACL injury.4 Henning viewed more than 500 videos of ACL injuries and concluded that the overwhelming majority of the injuries occurred without contact. In female basketball players, he notes that the most common noncontact injury mechanisms were planting and cutting, straight knee landing, and 1-step stopping with an extended knee. Based on these observations, the Henning Program focused on avoiding these positions and supplanting them with an accelerated rounded turn, bent-knee landing, and a 3-step stop with the knees flexed, respectively. This type of training has been expanded by others and could be generally categorized as a technique-movement awareness program.

EVIDENCE

The knee ligament injury prevention (KLIP) training program is a low-intensity plyometric training program applicable for broad use in any active population.5 The KLIP emphasizes landing mechanics with neuromuscular control at landing. Irmischer and colleagues5 randomized 28 active college-age female individuals to a KLIP or control group, and showed that a 9-week KLIP program improved landing mechanics and decreased peak vertical impact force, as well as the rate of force displacement.

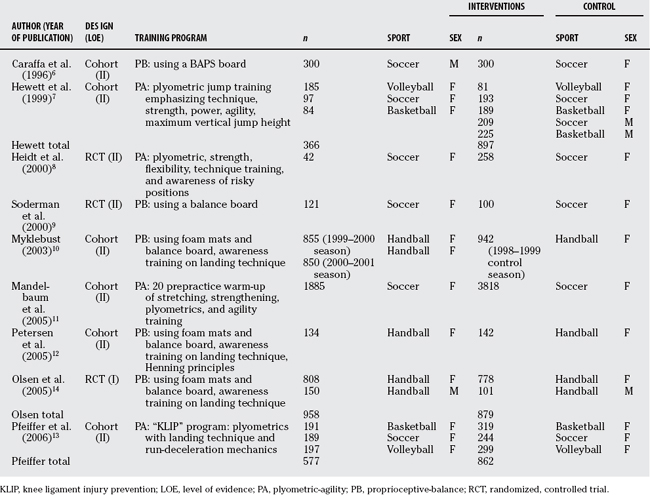

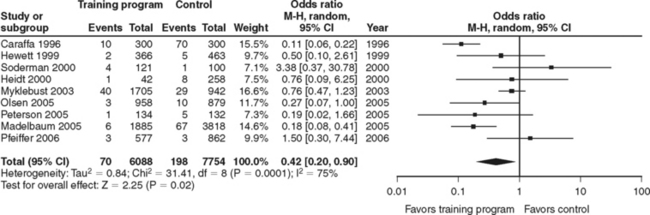

Nine studies of adequate design for potential casual inference, eight Level II studies,6–13 and one Level I study14 have investigated ACL prevention training programs; the characteristics of these studies are listed in Table 92-1. The results of the individual studies are listed in Figure 92-1 together with a forest plot graphically displaying the point estimates on a common scale. These studies are clinically and methodologically heterogeneous with a significant test for statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.0001). A random-effects model was developed in Review Manager 515 using the method of DerSimonian–Laird to calculate an overall pooled estimate of effect (odds ratio [OR], 0.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.20–0.90) to account for between-study variation (heterogeneity). Considerable differences have been found in the type and frequency of training programs used, the study populations at risk, method of diagnosing ACL injury, and study designs. To that end, it is not surprising that the findings of these studies are not all compatible, and the pooled estimate of effect should be viewed with caution. Indeed, future studies should heed the advice of Padua and Marshall,1 who have pointed out that it is imperative that future studies adopt a standardized method of verifying and reporting the incidence of ACL injury with a clear definition of exposure.

Based on a number-needed-to-treat analysis, Grindstaff and coworkers16 pooled the results of 5 studies to estimate, for a competitive season, that it would take 89 subjects participating in a neuromuscular control training program to prevent 1 ACL injury (95% CI, 66–139).

Hewett and investigators17 performed a meta-analysis to estimate the overall effect of injury prevention programs on the odds of ACL injury and reported a protective pooled OR of 0.40 (95% CI, 0.26–0.62). The meta-analysis in this review differs from that of Hewett et al.17 in its methodology; specifically, Hewett et al.17 pooled the results of six studies under the fixed-effect assumption of homogeneity. The meta-analysis in the current review includes several additional studies and accounts for the heterogeneity with a more conservative random-effects model.

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

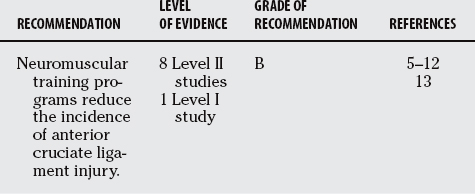

The available published evidence regarding preventive training programs is primarily Level II17 (Fair Evidence), save for Olsen and researchers’14 Level I trial (Good Evidence). Based on this classification schema of evidence, a B grade of recommendation supports the use of training programs utilizing plyometric-agility or proprioception-balance exercises, or both, to reduce the incidence of ACL injuries. Many of the studies used a multidimensional approach (incorporating injury awareness, proprioception-balance, plyometric-agility); however, the specific aspects of these training programs that result in risk reduction are not entirely transparent, such as the relative contributions and/or interactions between the different components. Other areas of uncertainty include: (1) Is there a dose response to the intervention? In other words, is there a minimum amount necessary to be effective, and/or does more participation in a training program lead to further risk reduction? (2) Is there a temporal relation that is important and is it sport specific (preseason, in season, postseason)? (3) What is the duration of the effect?

Fair evidence exists based on inconsistent findings from Level II studies supporting the use of neuromuscular training programs for the prevention of ACL injury. No evidence suggests that such programs are unsafe or lead to serious adverse advents. Future randomized trials using ACL injury as the primary end point could strengthen this body of evidence and potentially address areas of uncertainty. Table 92-2 provides a summary of recommendations.

1 Padua DA, Marshall SW. Evidence supporting ACL-injury-prevention exercise programs: A review of the literature. Ath Ther Today. 2006;11:11-23.

2 Griffin LY, Albohm MJ, Arendt EA, et al. Understanding and preventing noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: A review. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1512-1532.

3 Hurd WJ, Chmielewski TL, Axe MJ, et al. Differences in normal and perturbed walking kinematics between male and female athletes. Clin Biomech. 2004;19:465-472.

4 Griffin L. Prevention of Noncontact ACL Injuries. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2001;93.

5 Irmischer BS, Harris C, Pfeiffer RP, et al. Effects of a knee ligament injury prevention exercise program on impact forces in women. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18:703-707.

6 Caraffa A, Cerulli G, Projetti M, et al. Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer. A prospective controlled study of proprioceptive training. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1996;4:19-21.

7 Hewett TE, Lindenfeld TN, Riccobene JV, et al. The effect of neuromuscular training on the incidence of knee injury in female athletes. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:699-706.

8 Heidt RSJr, Sweeterman LM, Carlonas RL, et al. Avoidance of soccer injuries with preseason conditioning. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:659-662.

9 Soderman K, Werner S, Pietila T, et al. Balance board training: Prevention of traumatic injuries of the lower extremities in female soccer players? A prospective randomized intervention study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:356-363.

10 Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, Braekken IH, et al. Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female team handball players: A prospective intervention study over three seasons. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:71-78.

11 Mandelbaum BR, Silvers HJ, Watanabe DS, et al. Effectiveness of neuromuscular and proprioceptive training program in preventing anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1003-1010.

12 Petersen W, Braun C, Bock W, et al. A controlled prospective case control study of a prevention training program in female team handball players: The German experience. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125:614-621.

13 Pfeiffer RP, Shea KG, Roberts D, et al. Lack of a knee ligament injury prevention program on the incidence of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1769-1774.

14 Olsen OE, Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, et al. Exercises to prevent lower limb injuries in youth sports: Cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330:449.

15 Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2007.

16 Grindstaff TL, Hammill RR, Tuzson AE, et al. Neuromuscular control training programs and noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury rates in female athletes: A numbers-needed-to-treat analysis. J Athl Train. 2006;41:450-456.

17 Hewett TE, Ford KR, Myer GD. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Part 2, a meta-analysis of neuromuscular interventions aimed at injury prevention. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:490-498.