ARDS, SARS, and Sepsis

I Definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

A ARDS: A diffuse, heterogenous inflammatory response of the lungs, resulting in hypoxemia, consolidation, and decreased compliance.

B The American-European Consensus Conference has provided the most precise definition of this syndrome (Box 23-1):

1. Sudden and acute onset of disease.

2. The presence of bilateral pulmonary infiltrates in all lung regions seen on frontal chest radiograph.

3. A pulmonary artery wedge pressure ≤18 mm Hg or a lack of clinical evidence of left atrial hypertension.

4. Severe hypoxemia: A Pao2/FIO2 ≤200 mm Hg regardless of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) or FIO2 level.

5. A less severe form of ARDS, referred to as acute lung injury (ALI), is defined as a Pao2/FIO2 ratio ≤300 mm Hg.

C Although the aforementioned definition has become the most accepted definition of ALI/ARDS, it has been shown that alterations in FIO2 and PEEP can markedly affect the Pao2:FIO2 ratio, moving patients into and out of the classification of ALI or ARDS.

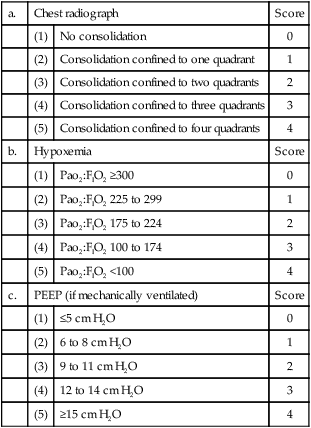

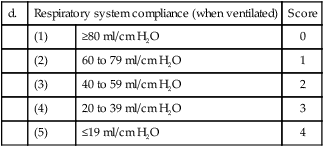

D Others have used varying assessment mechanisms to define ARDS. The most commonly reported is the Murray lung injury score.

1. This score is based on four areas:

| a. | Chest radiograph | Score | |

| (1) | No consolidation | 0 | |

| (2) | Consolidation confined to one quadrant | 1 | |

| (3) | Consolidation confined to two quadrants | 2 | |

| (4) | Consolidation confined to three quadrants | 3 | |

| (5) | Consolidation confined to four quadrants | 4 | |

| b. | Hypoxemia | Score | |

| (1) | Pao2:FIO2 ≥300 | 0 | |

| (2) | Pao2:FIO2 225 to 299 | 1 | |

| (3) | Pao2:FIO2 175 to 224 | 2 | |

| (4) | Pao2:FIO2 100 to 174 | 3 | |

| (5) | Pao2:FIO2 <100 | 4 | |

| c. | PEEP (if mechanically ventilated) | Score | |

| (1) | ≤5 cm H2O | 0 | |

| (2) | 6 to 8 cm H2O | 1 | |

| (3) | 9 to 11 cm H2O | 2 | |

| (4) | 12 to 14 cm H2O | 3 | |

| (5) | ≥15 cm H2O | 4 | |

| d. | Respiratory system compliance (when ventilated) | Score | |

| (1) | ≥80 ml/cm H2O | 0 | |

| (2) | 60 to 79 ml/cm H2O | 1 | |

| (3) | 40 to 59 ml/cm H2O | 2 | |

| (4) | 20 to 39 ml/cm H2O | 3 | |

| (5) | ≤19 ml/cm H2O | 4 | |

2. A score of 0 to 4 is given for each of the above available, and then scores are averaged.

3. ARDS is defined as a score >2.5; a mild to moderate injury is scored 0.1 to 2.5; and 0.0 indicates no lung injury.

E It is important to remember that there is no test or measurement that can precisely define or identify ARDS. Diagnosis is always based on the signs and symptoms described previously.

F Until a test is identified that can definitively diagnose ARDS there will continue to be controversy whether a patient truly has ARDS.

G Many believe there is a genetic predisposition of ARDS and that one day an “ARDS gene” will be identified.

II Incidence and Mortality of ARDS

A Because no precise definition for ARDS exists, it is difficult to precisely identify its occurrence in the general population.

B However, the epidemiologic data currently available indicate that approximately 3 to 19 cases of ARDS occur in every 100,000 individuals per year.

C Similarly the reported mortality of ARDS varies widely. Early reports indicate a mortality of 80% to 90%.

D Randomized clinical trials evaluating select populations of ALI and ARDS patients have reported mortalities as low as 25% to 30%.

E Epidemiologic data from widely distributed intensive care units indicate that the mortality for all patients with ARDS is still approximately 50% to 60%.

A By 1 year after hospital discharge most patients have regained the majority of pulmonary function lost during the acute illness.

B However, most have a decreased diffusing capacity, resulting in desaturation with exertion.

C At 1 year after discharge, feelings of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress also are common.

D Quality-of-life surveys also indicate decrements in general and respiratory-associated parameters at 1 year after discharge.

A Two general categories of causative factors have been defined: Direct or primary pulmonary lung injury, and indirect or secondary nonpulmonary cause of lung injury.

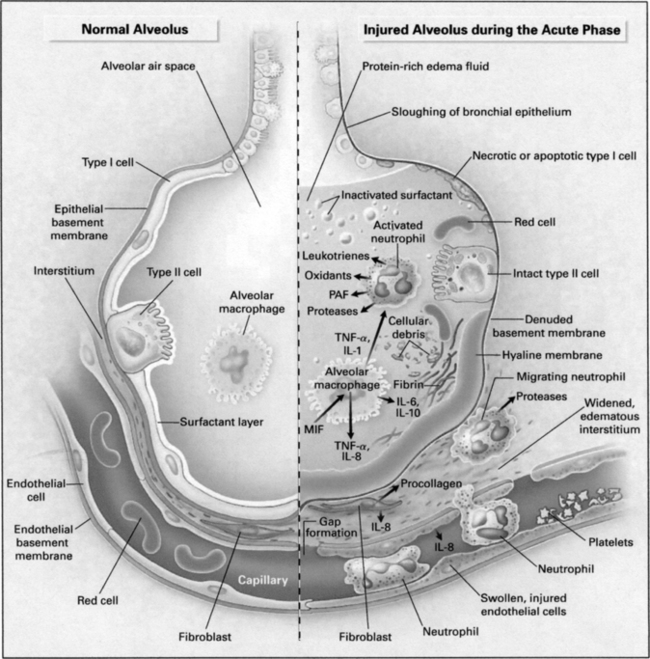

A ARDS is characterized by diffuse alveolar damage and microvascular injury.

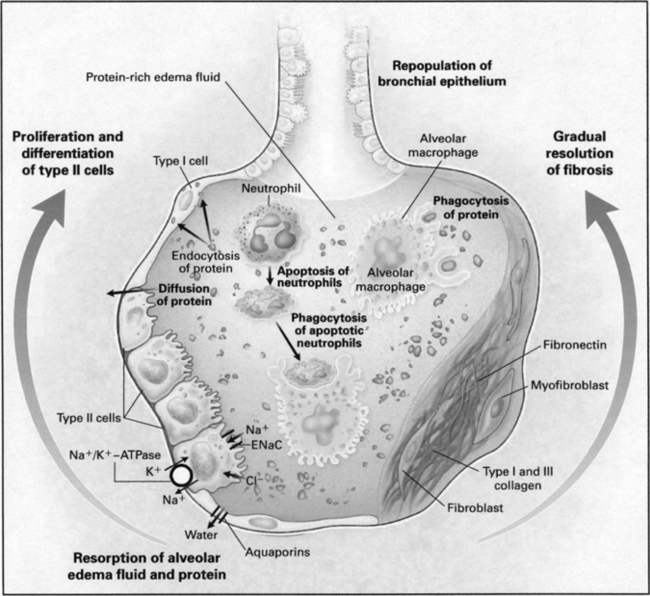

B Three distinct phases of ARDS/ALI from a pathophysiologic perspective have been defined: Exudative phase, fibroproliferative phase, and resolution phase.

C ARDS does not necessarily progress to the fibroproliferative phase; many patients rapidly move from the exudative phase to the resolution phase.

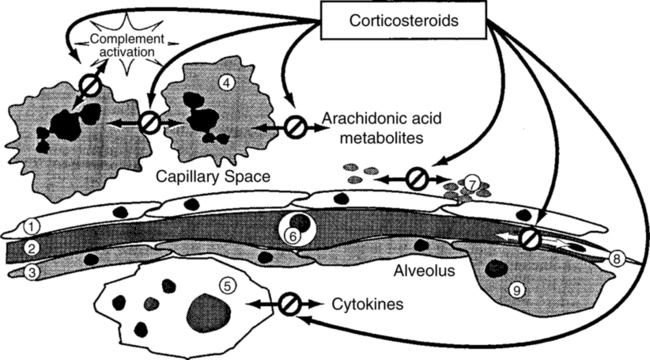

D Exudative (acute) phase (Figure 23-1)

1. On histologic examination of the lung the following are observed:

2. The adhesion and activation of neutrophils lead to the secretion of proinflammatory mediators, potentially leading to more injury (see Figure 23-1; Table 23-1).

TABLE 23-1

Proinflammatory Mediators Associated with the Development of ARDS/ALI

| Mediator Category | Mediators |

| Tumor necrosis factors | TNF-α, TNF-β |

| Interleukins | IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 |

| Chemokines | IL-8, MIP-1, MCP-1, growth-regulated peptides |

| Colony-stimulating factors | G-CSF, GM-CSF |

| Interferon | IFN-β |

ARDS, Acute respiratory distress syndrome; ALI, acute lung injury.

From Wiedemann H: Systemic Pharmacolic Therapy of ARDS Resp Care Clin North Am 3:732, 1998.

3. The composition of pulmonary surfactant and its quantity are altered, increasing surface tension.

4. As the disease progresses deadspace ventilation increases.

5. Early in this exudative phase the major gas exchange issue is oxygenation. As this phase transitions into the fibroproliferative phase, ventilation generally becomes more of a problem.

6. The exudative phase generally lasts for approximately 3 to 7 days.

1. In this stage the alveolar damage progresses, and pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary fibrosis develop.

2. Alveolar cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts also proliferate.

3. Microvascular thrombosis and vascular injury become more prominent.

4. For those who do not improve, multiorgan system failure develops.

5. The proinflammatory mediators released in the lung can migrate into the systemic circulation under conditions of high peak alveolar pressure and repetitive opening and closing of unstable lung units. This process is believed to be at least partially responsible for the development of multiorgan system failure.

6. Systemic release of proinflammatory mediators in direct and indirect ARDS also occurs and can cause multiorgan system failure.

7. Most patients with ARDS who die do so because of multiorgan system failure, not respiratory failure.

8. The fibroproliferative phase can last for a few days or for weeks.

A As a result of the damage at the alveolar-capillary membrane, lung compliance decreases.

B Functional residual capacity also decreases.

VII Ventilator-Induced Lung Injury

A It has become increasingly clear from laboratory and clinical studies that inappropriate mechanical ventilation can cause lung injury indistinguishable from other forms of ARDS.

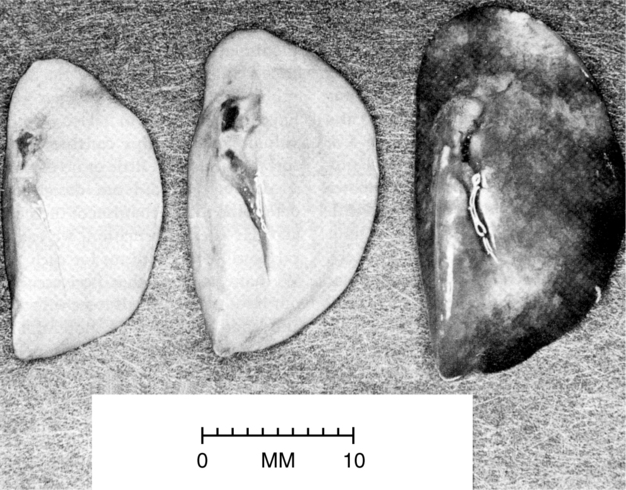

B The most common form of injury caused by the ventilator has been referred to as volutrauma, defined as end-inspiratory overdistention (Figure 23-3).

1. The term volutrauma is used because it is believed that localized increases in end-inspiratory lung volume cause the injury.

2. Most probably it is the localized stress and strain on the alveolar-capillary membrane associated with any tidal volume (Vt) that increases peak alveolar pressure causing the injury.

3. Clearly there is debate as to the exact cause of this injury: volume or pressure.

4. Many believe there is a safe peak alveolar pressure and that the lung is not damaged regardless of Vt if pressure is kept below this level.

5. Available data indicate this level is approximately 25 to 30 cm H2O.

C Barotrauma: Essentially the extreme of volutrauma, in which the end-inspiratory stress is so great that tears are created at the alveolar surface, allowing air to dissect through facial planes ending in various compartments (Figure 23-4).

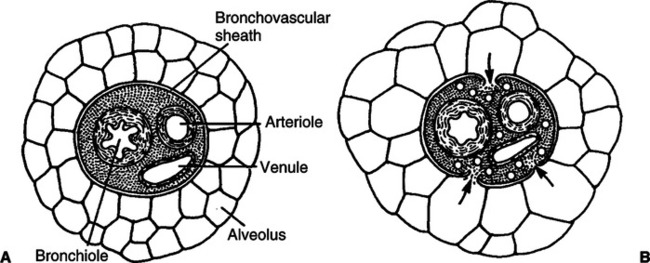

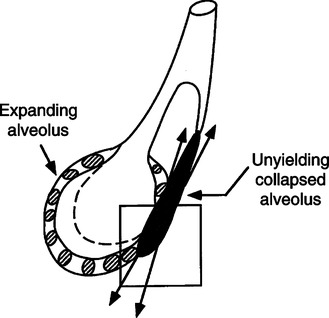

D Atelectrauma: Injury that is a result of unstable lung units opening during inspiration and being allowed to close during exhalation.

1. The shear stress caused by this process on the walls of the unstable alveoli can exceed 140 cm H2O when the peak alveoli pressure in adjacent open alveoli is 30 cm H2O (Figure 23-5).

2. Many believe this injury can be as severe as volutrauma.

3. The application of PEEP should always be focused on preventing unstable lung units from collapsing once they are opened.

E The development of volutrauma and atelectrauma causes two other mechanisms to occur that can extend the level of lung injury and cause systemic injury.

1. Biotrauma: A term used to identify the activation of inflammatory mediators by the aforementioned injuries (i.e., in the presence of volutrauma or atelectrauma there is an increase within the lung of the release of proinflammatory mediators).

2. Translocation of substances from the lung into systemic circulation.

a. Injurious ventilation not only affects the alveoli epithelium but also can cause tears in the capillary endothelium.

b. As a result organisms and inflammatory mediators can move from the lung into systemic circulation when VILI is present.

c. Thus VILI can cause distal organ failure or sepsis.

d. Many believe that the lung is the engine that drives the development of multiorgan system failure.

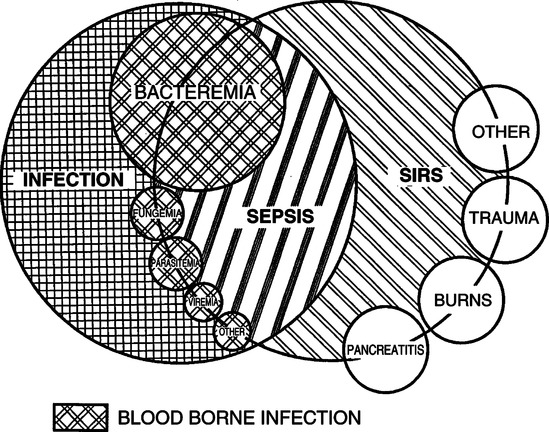

A Infection: A microbial phenomenon characterized by an inflammatory response to the presence of microorganisms or the invasion of normally sterile host tissue by those organisms.

B Bacteremia: The presence of viable bacteria in the blood.

C Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS): Systemic inflammatory response to a variety of severe clinical insults, defined as the presence of two or more of the following:

1. Temperature: >38° C or <36° C

2. Pulse: >90 beats/min at rest

3. Tachypnea at rest: >20 breaths/min or Paco2 <32 mm Hg

4. White blood cell count: >12,000/mm3 or <4000 mm3 or >10% bands

D Sepsis: Systemic response to infection manifested by two or more of the following:

1. Temperature: >38° C or <36° C

2. Pulse: >90 beats/min at rest

3. Tachypnea at rest: >20 breaths/min or Paco2 <32 mm Hg

4. White blood cell count: >12,000/mm3 or <4000 mm3 or >10% bands

E The definitions for SIRS and sepsis are the same except SIRS is not caused by an infection. When infection develops, SIRS becomes sepsis (see Figure 23-6).

F Severe sepsis: Sepsis associated with organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion, or hypotension. Hypoperfusion and perfusion abnormalities may include but are not limited to lactic acidosis, oliguria, or an acute alteration in mental status.

G Septic shock: Sepsis with hypotension, despite adequate fluid resuscitation, along with the presence of perfusion abnormalities that may include but are not limited to lactic acidosis, oliguria, or an acute alteration in mental status. Patients who are taking inotropic or vasopressor agents may not be hypotensive at the time that perfusion abnormalities are measured.

H Hypotension: A systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or a reduction of >40 mm Hg from baseline.

I Multiorgan dysfunction syndrome: Presence of altered organ function in acutely ill patients such that homeostasis cannot be maintained without intervention.

J Approaches to managing sepsis include:

1. Appropriate antibiotic therapy addressing the underlying infection.

2. Activated protein C (Drotrecogin alfa activated) has been successful in cases of severe sepsis.

3. Antithrombin therapy, although the data supporting its use are controversial.

4. Heparin in combination with activated protein C or antithrombin therapy has demonstrated some benefit.

5. Corticosteroid therapy has also demonstrated some benefit, but again its use is controversial.

6. Many have recommended the combined use of all of these therapies in a stepwise approach. However, no definitive therapy for sepsis exists.

IX Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

A SARS is an unusual atypical pneumonia that emerged in November 2002 in mainland China.

B Approximately 20% of those diagnosed with SARS develop ARDS/ALI, and approximately 50% of these patients die.

C Thus SARS has an overall mortality of approximately 10%.

D The causative agent for SARS is a coronavirus (SARS-CoV) that can cause disease in animals and humans and can easily be transmitted from patient to patient and from animal to human. This group of viruses typically was responsible for some forms of the common cold.

E There is no rapid test that is able to identify the virus; identification may take weeks. As a result diagnosis currently is based on the patient meeting a case definition of the disease:

1. A hospitalized patient with radiographically confirmed pneumonia or ARDS without identifiable etiology.

2. One of the following risk factors within 10 days before onset of illness:

a. Travel to mainland China, Hong Kong, or Taiwan or close contact with an ill person with a history of recent travel to these areas.

b. Employment in an occupation with a high risk of SARS-CoV exposure (e.g., health care workers and individuals working with the virus).

c. Part of a cluster of cases of atypical pneumonia without an alternative diagnosis.

F Patients with SARS should be on complete airborne and droplet precautions (see Chapter 3).

G All health care workers treating infected patients should at least use the following:

H During high-risk procedures (e.g., intubation and bronchoscopy), an isolation hood “powered air-purifying respirator” should be worn.

X Pharmacologic Management of ARDS

A A number of different pharmacologic agents have been used to manage ARDS (Table 23-2).

TABLE 23-2

Proposal Pharmacologic Therapies for ARDS/ALI with “Potential” Mechanisms of Action

| Drug | Mechanisms of Action |

| Activated protein C (rhAPC) | Inhibition of plasminogen activator inhibitor |

| Inhibition of leukocyte adhesion and inflammatory cytokines | |

| Inhibition of neutrophil accumulation | |

| Antiadhesion molecules | Inhibition of leukocyte adherence to endothelium |

| Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) | Activation of membrane-bound guanylate cyclase and cyclic GMP production |

| Corticosteroids | Inhibition of arachidonic acid metabolites |

| Inhibition of complement-induced neutrophil aggregation | |

| Inhibition of inflammatory cytokines | |

| Modification of fibrogenesis | |

| Suppression of cytokine release from macrophages | |

| Suppression of platelet-activating factor and nitric oxide production | |

| Cytokine antagonists | Inhibition of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., monoclonal antibodies and receptor antagonists) |

| Ketoconazole | Inhibition of thromboxane synthetase |

| Inhibition of procoagulant activity by macrophages | |

| Blockade of 5-lipoxygenase | |

| Lisofylline | Inhibition of TNF release |

| Inhibition of neutrophil accumulation | |

| Inhibition of inflammatory cytokines | |

| N-acetylcysteine, procysteine | Repletion of glufathilone stores (antioxidant activity) |

| Prostaglandin E1 | Inhibition of mediator release from granulocytes |

| Pulmonary vasodilation | |

| Nitric oxide | Increased cyclic GMP levels |

| Pulmonary vasodilation | |

| Improved oxygenation | |

| Surfactant | Replaces endogenous surfactant |

| Improved pulmonary compliance | |

| Improved gas exchange |

GMP, Guanosine monophosphate; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

From Wiedemann HP, Arroliga AC, Komara JJ: Emerging pharmacologic approaches in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir Care Clinics N Am 9:419-435, 2003.

B However, none of these agents has demonstrated a decrease in mortality in ARDS.

C Activated protein C has been shown to decrease mortality in sepsis by approximately 6% but not necessarily sepsis associated with ARDS.

D Corticosteroids in a small trial of 24 patients with unresolved ARDS did demonstrate improved outcome (Figure 23-7) (Meduri et al, 1998).

1. This study used prolonged administration of methylprednisolone, a loading dose of 2 mg/kg, followed by 2 mg/kg/day for 1 to 14 days, followed by a tapering dose to day 32.

2. However, because the number of patients was small and a crossover design was used, these results are considered preliminary, requiring additional studies.

3. Systemic steroid therapy in patients with ARDS also has been associated with severe and prolonged paresis with muscle wasting and weakness.

E Inhaled nitric oxide does improve Pao2 and decreases pulmonary hypertension in those with ARDS/ALI, but at least four randomized controlled trials of inhaled nitric oxide use in ARDS have been negative. Nitric oxide use in patients with ARDS/ALI is not recommended (see Chapter 34).

F Surfactant: A number of clinical trials have evaluated surfactant therapy in adult ARDS; however, none has demonstrated benefit. Trials are ongoing, but at this time surfactant cannot be recommended for those with adult ARDS.

G None of the other agents listed in Table 23-2 have shown improved outcome when used to manage ARDS/ALI, and none are recommended as treatment.

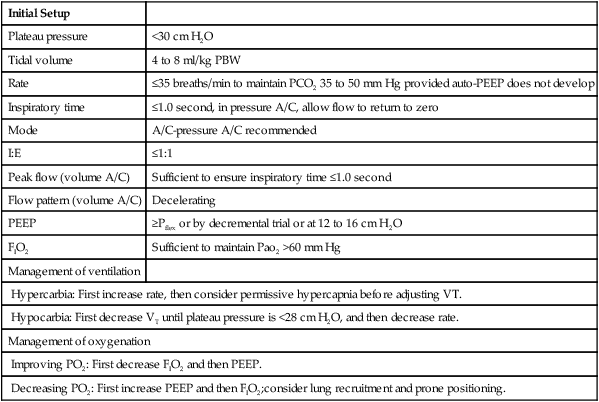

XI Ventilator Management (Table 23-3)

TABLE 23-3

Ventilatory Management of ARDS

| Initial Setup | |

| Plateau pressure | <30 cm H2O |

| Tidal volume | 4 to 8 ml/kg PBW |

| Rate | ≤35 breaths/min to maintain PCO2 35 to 50 mm Hg provided auto-PEEP does not develop |

| Inspiratory time | ≤1.0 second, in pressure A/C, allow flow to return to zero |

| Mode | A/C-pressure A/C recommended |

| I:E | ≤1:1 |

| Peak flow (volume A/C) | Sufficient to ensure inspiratory time ≤1.0 second |

| Flow pattern (volume A/C) | Decelerating |

| PEEP | ≥Pflex or by decremental trial or at 12 to 16 cm H2O |

| FIO2 | Sufficient to maintain Pao2 >60 mm Hg |

| Management of ventilation | |

| Hypercarbia: First increase rate, then consider permissive hypercapnia before adjusting VT. | |

| Hypocarbia: First decrease VT until plateau pressure is <28 cm H2O, and then decrease rate. | |

| Management of oxygenation | |

| Improving PO2: First decrease FIO2 and then PEEP. | |

| Decreasing PO2: First increase PEEP and then FIO2;consider lung recruitment and prone positioning. | |

A Refer to Chapters 39, 40, and 41.

B A lung protective strategy should always be used when ventilating patients with ALI or ARDS.

C This strategy centers on avoiding overdistention and repetitive opening and closing of unstable lung units.

D Overdistention is primarily avoided by maintaining plateau pressures <30 cm H2O; the lower the plateau pressure, the greater the likelihood of avoiding VILI and increasing survival. Vt also should be low, in the range of 4 to 8 ml/kg for most patients.

1. Tidal volume level is set based on the plateau pressure.

2. Paco2 level should be maintained by adjusting rate, not Vt.

3. Rates up to approximately 40 breaths/min may be used. Rate is only limited by the development of auto-PEEP.

4. Once auto-PEEP develops, the benefit of increasing the rate is lost regardless of mode of ventilation.

E Repetitive opening and collapse of unstable lung units can be minimized by appropriate PEEP.

1. The data to date indicate PEEP greater than the lower inflection point on the pressure-volume (P-V) curve of the respiratory system (Pflex) is the most appropriate initial level to set.

2. This level can be determined by performing a P-V curve, or it can be estimated by a decremental PEEP trial (see Chapter 40).

3. If neither of the above approaches is used, initial PEEP level can be set at approximately 12 to 16 cm H2O.

F Any mode may be used, but pressure assist/control (A/C) allows for precise targeting of plateau pressure and is recommended.

G Inspiratory time should be set at ≤1.0 second. It should be long enough to maximize Vt delivery in pressure A/C (i.e., flow should return to zero before the end of the breath).

H Inspiration-to-expiration (I:E) ratios should be ≤1:1; no benefit of the use of an inverse I:E ratio has been demonstrated.

I Set FIO2 high enough to ensure a Pao2 >60 mm Hg.

1. Ventilation is primarily managed by adjusting respiratory rate.

2. However, if increasing rate because of hypercarbia results in auto-PEEP, permissive hypercapnia may be necessary.

3. If patients are hemodynamically stable without head trauma, Pco2 into the 70s and 80s is generally well tolerated if increased to this level slowly.

4. The real concern with permissive hypercapnia is acidosis. Most patients tolerate a pH as low as 7.25.

5. However, the older the patient, or the presence of cardiovascular or renal disease and hemodynamic instability, the less likely permissive hypercapnia will be tolerated.

6. If patients cannot tolerate permissive hypercapnia, the Vt may be increased; however, care not to exceed a plateau pressure of 30 cm H2O must be exercised. Allowing plateau pressures to exceed 30 cm H2O unless the patient has decreased chest wall compliance increases the likelihood of VILI and a poor outcome (see Chapter 41).

7. In the presence of hypocarbia Vt should be decreased first to maintain plateau pressure as low as possible; then rate can be decreased.

1. Before setting PEEP and FIO2 a lung recruitment maneuver can be performed in patients who are hemodynamically stable (see Chapter 40).

2. A recruitment maneuver ideally is performed after initial stabilization on the mechanical ventilator.

3. PEEP and FIO2 are then set: PEEP ≥ Pflex or by decremental trial or at 12 to 16 cm H2O, and then FIO2 is set to maintain Po2 >60 mm Hg.

4. If oxygenation is excessive FIO2 should be first reduced until the FIO2 is <0.50, after which PEEP may be reduced. PEEP should always be reduced once the FIO2 = 0.40.

5. If oxygenation is inadequate, PEEP should be first increased, and then FIO2. PEEP should always be increased in small steps (2 cm H2O), and its response assessed (both oxygenation and cardiovascular; see Chapter 40).

6. Patients with refractory hypoxemia not responding to PEEP, FIO2, and recruitment maneuvers should be considered for prone positioning (see Chapter 45).

L Weaning from ventilatory support should be by spontaneous breathing trial (see Chapter 41).

1. Before or between spontaneous breathing trials pressure support ventilation is frequently best tolerated.

2. Other approaches to weaning may be tried, but a spontaneous breathing trial has been demonstrated most efficacious.

M Other modes of ventilation, such as high frequency oscillation, inverse ratio ventilation, and airway pressure release ventilator or bilevel ventilation, have not demonstrated benefit over the use of A/C ventilation in ARDS.