Chapter 9 Approaches to risk assessment 2

Risk assessment is best described in terms of human endeavour, not in the language of scientific measurement.1

Screening for risk

Screening for risk is a routine part of all assessments. Screening for suicide risk will be used as the example to describe the process. The assessment of suicidal risk is one of the most common and basic procedures in psychiatry.2 It is probably the purest example of a risk assessment as the process requires close interaction with the patient, is incremental in that the next question is based on the response to the previous question, and interventions will be based on both treating the underlying illness and preventing the risk behaviour from occurring.

If the verbal and/or non-verbal response to these opening questions is positive, the clinician will then continue to ask more probing questions until the extent of the preoccupation with suicide is apparent. From there, in conjunction with the rest of the assessment, management decisions will be made. For suicide,

because of the acuity which may be present, it is not uncommon for a full assessment to be conducted during the first meeting to determine the level of risk. This is less likely to be the case for violence where the focus is more often on preventing future episodes.

The negatives if the risk is minimal will make the process quick, the discovery of positives and consideration of interventions makes it worthwhile.3

There are screening tools available (one is included in Chapter 15, risk of violence) but a useful rule of thumb is to consider a more detailed assessment if:

• there are substantive risk issues

• the patient is likely to require treatment after hours

• the patient is likely to make contact with the service in between appointments

• the patient is admitted for treatment to either a respite facility or hospital

• there is a past history of violence, self-harm or suicide attempts.

BOX 9.2 CLINICAL TIP

OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER (OCD)4

• Obsessional ruminations are often misinterpreted as indicating risk. There are no recorded cases of a person with OCD carrying out their obsession. By definition, such intrusions are unacceptable and ego-dystonic.

• Risk in OCD is usually related to the consequences of acting on compulsions and urges in order to avoid the anxiety-provoking situations; for example, harm from washing hands too frequently, harm from compulsive hoarding.

• Risk to others may occur when well-meaning attempts are made to prevent compulsive behaviours being carried out.

• Secondary co-morbid illnesses such as depression, which is driven by the distress of the OCD, may create risk of suicide and should be assessed.

Assessment and documentation exercise

The first exercise in this section starts the process of assessing and documenting risk. Often, the first presentation is a phone call or an assessment in the Emergency Department (ED). Information may be limited but a start needs to be made. The initial identification of the risk may also create anxiety on the part of the clinician. The process of simply documenting what is known creates a degree of objectivity which will immediately reduce anxiety. The purpose of the following exercise is to simply practise documenting identified risk and consider to whom, when, where and what means might be used. Practising the exercises will give you an opportunity to get used to the routine questions which are central to any risk assessment. With practice, there will be increasing familiarity which is a risk management skill in its own right. Familiarity with the process can reduce risk by a factor of 17.5

For each of the examples below answer the following questions.

Exercise 1 — Monique

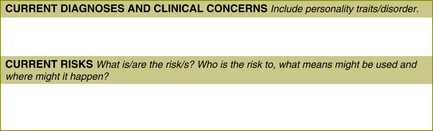

Monique is a 28-year-old woman with schizophrenia. Her boyfriend has recently left her and staff in the supported accommodation home in which she lives report that she is tearful, distraught and withdrawn. They wonder if she is going to kill herself. The staff phone you and your task is to complete the risk documentation on the triage form. Refer to the template in Figure 9.1. The completed form appears in Appendix 3.

Comment on the completed form

For Monique, she will need to be seen relatively urgently for a more complete assessment. The staff in the supported accommodation are anxious and part of the task of the assessment will be to manage this anxiety. Hopefully, she will already have a risk management plan which will make the process easier. This is how the risk may be documented in a triage form written by a duty worker receiving the call from the supported accommodation home. See Appendix 1 for an example of a triage form, including a place for documenting risk.

Exercise 2 — Phoebe

Use the risk assessment template in Figure 9.1. The completed form appears in Appendix 3.

Exercise 3 — Colin

Use the risk assessment template in Figure 9.1. The completed form appears in Appendix 3.

Comment on the completed form

For Colin, the risk assessment starts immediately with your interpretation of his intent stare. His opening statement, ‘There’s nothing wrong with me’, is likely to be made aggressively. Is this statement made because he is frightened or angry or both? His stare and the tone of his voice are important factors which will help in the identification of the potential risk and in the determination of its severity. Commenting on the lack of knowledge of whether a weapon exists or not is important for the continuing assessment. The answer has not commented on the smell of cannabis. Is he currently intoxicated? Is cannabis use a risk factor for violence — possibly not unless accompanied by psychosis. Does he have a psychotic illness related to substance abuse or is his psychosis possibly schizophrenia? There are a lot of unknowns in this example which will be common in an acute presentation.

Exercise 4 — Rebecca

Use the risk assessment template in Figure 9.1. The completed form appears in Appendix 3.

Discussion of exercises 1–4

You have been given limited information in the examples in these exercises. Nonetheless, being able to document the risk will assist in developing an immediate plan to deal with the crisis and, once the patient has stabilised somewhat, consideration can be given as to whether a more complete assessment needs to be undertaken. This is developed further in Chapter 11.

Exercise 5 — Monique (continued)

Refer to exercise 1 (page 76) for Monique’s story.

BOX 9.3 RISK SCREENING

• Documenting the risk allows for a degree of objectivity which reduces anxiety.

• Predicting when it may happen is difficult.

• If uncertain about whether to complete a full risk assessment, do it. If the risk is minor, the time spent will be small.

• An index of suspicion should be taken into all interviews to prompt for risk as patients will often not disclose risk issues spontaneously.

Monique was in a relationship with another resident at the hostel.

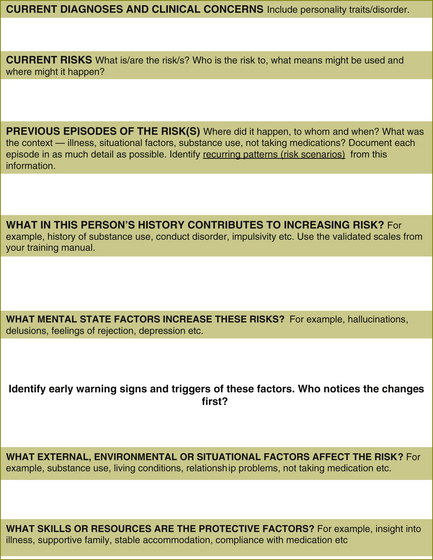

From the information given, document the current risk. Identify static and dynamic risk factors which will help you in your assessment of the risk of suicide. Include the protective factors. Use the risk factors for suicide in Table 9.1 to help you. Are there any patterns?As you do this exercise, imagine you are discussing your thinking with Monique.

| Risk factors for suicide |

|---|

| Static factors |

• Current suicidal ideation, communication and intent. Feelings of desperation, abandonment, hopelessness, rage, self-hatred or anxiety.

• Co-morbid depression. The more severe the illness, the greater the risk.

• Other psychiatric illness with affective component.

• Current diagnosis of personality disorder, especially borderline and antisocial personality disorders.

• Impaired rational thinking: especially schizophrenia and psychosis.

Use the template in Figure 9.2, over the page. The completed risk assessment and management form appears in Appendix 3.

Exercise 6 — Colin (continued)

Refer to exercise 3 (page 77) for Colin’s story.

In ED, Colin allows you to take a history. There is a significant family history of abuse, mental health issues and substance misuse. For the last 10 years Colin has been smoking five joints of cannabis per day and tends to drink between 10 and 20 cans of beer per week. He says that approximately 6 months ago, he felt that his flatmate became more interested in his girlfriend and wondered if the flatmate was putting cameras in the ceiling to watch him making love to her. Initially he thought that this was a ridiculous idea but he became sufficiently concerned over a period of time to start checking around his room for hidden cameras and tape recorders. Shortly after this, Colin developed an unshakable idea — the newsreader on the television was giving him special messages.

From the information given, document the current risk, identify static and dynamic risk factors which will help you in your assessment of the risk of violence. Include the protective factors. Use the risk factors for violence in Table 9.2 to help you. Are there any patterns? As you do this exercise, imagine you are discussing your thinking with Colin.

| Risk factors for violence |

|---|

| Static factors |

• Psychosis — is the patient threatened, frightened and are normal controls overridden?

• Does the patient feel persecuted?

• Is the patient having command hallucinations?

• Changing symptoms. A tendency to act on symptoms.

• Impulsivity. Lack of Insight.

• Violent thoughts being expressed? Morbid jealousy?

• Threatening or fearful behaviour.

• Current diagnosis of personality disorder — especially psychopathy but include antisocial personality disorder.

Use the template in Figure 9.2. The completed risk assessment and management form appears in Appendix 3.

Discussion of documentation of risk assessment

Completing these exercises will give you some familiarity with the process of doing a risk assessment. Using the risk tool makes it easier for other clinicians, the patient and their family to make use of the information. However, for clinicians doing routine assessments, it can be time consuming to complete the documentation in this format. In some circumstances it may be sufficient to document the risk in a narrative form as a paragraph with the simple heading, ‘Risk Assessment’. Two examples appear below.

Comment

In both of these examples, which were taken directly from patients’ notes and de-identified, the current risks have been identified and consideration has been given to the static and dynamic and protective factors. Both of these examples have commented on the level of risk. Unfortunately it is not clear what low risk or low–moderate risk means from these examples. In the first example, the critical factor of relapse into substance abuse has been identified. The second example recommended that the risk be monitored although there was no timeframe mentioned. Also, in the second example multiple risk factors have been

BOX 9.5 RISK ASSESSMENT

• Structured clinical judgment (SCJ) combines clinical information and actuarial information known to be of relevance.

• SCJ allows for ease of review by others and is reproducible.

• Good risk assessment lays the foundation for good risk management.

• Good risk assessment should make it easier for the patient and family to share the risk and to participate in risk management.

• Good risk assessment should identify repetition of internal and situational factors, which are highly significant.6

• Signature risk signs and critical risk factors should be identified.

• ‘Risk scenarios’ — situations or states of mind where the risk is more likely to occur — should be identified.

• When uncertain, consider taking advice from colleagues, seeking supervision, getting a second opinion or discussing the case in the multidisciplinary team (MDT).

• Discussing risk openly with your patient does not increase the risk.

• When documenting risk, using a narrative style is easier for colleagues to read.7

• Imminence of risk is assessed at each meeting with the patient and is guided by the risk management and treatment plan.

identified with no particular critical factors noted. In neither example was the management of the risk documented. It is hoped that this was included in the management section of these patients’ documentation!

If need be, both of these examples could be adapted and put into the risk tool quite easily if it was thought the patient may present after-hours or in a crisis. Some clinicians might say that risk should always be documented separately and placed in the file in a place which is easily seen. This is discussed further in Chapter 11.

1 Murphy D. Risk assessment as collective clinical judgment. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2002;12:169–178.

2 Gutheil T.G., Schetky D. A date with death: management of time-based and contingent suicidal intent. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1502–1557. November.

3 Maden A. Treating Violence: a Guide to Risk Management in Mental Health. Oxford.: Oxford University Press; 2007.

4 Veale D., Freeston M., Krebs G., Heyman I., Salkovskis P. Risk assessment and management in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2009;15:332–343.

5 Williams J. A database method for assessing and reducing human error to improve operational performance. In: Hagen W., ed. ILEEE Fourth Conference on Human Factors and Power Plants. New York: Institute for Electrical and Electronic Engineers; 1988:200–231.

6 Winestock M. Risk assessment. ‘A word to the wise’? Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 1996;2:3–9.

7 Higgins N., Watts D., Bindman J., Slade M., Thornicroft G. Assessing violence risk in general adult psychiatry. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2005;29:131–133. 3–9.