Chapter 8 Approaches to risk assessment 1

Risk assessment is not a new technique, although the emphasis is different. It requires no more and no less than a full clinical history and examination.1

The process of risk assessment also allows for the development of rapport with the patient and should always be seen as a component of treatment, not just an exercise undertaken to fulfil bureaucratic requirements. As is increasingly the case with all clinical work, there should be an expectation that documentation will be shared with the patient. Every time the patient is seen, there should be an assessment for the imminence and previously identified patterns of risk. On an inpatient ward, this may happen every few minutes, whilst in an outpatient setting, it may only occur every 3–6 months when a stable patient is reviewed.

The process of risk assessment can be very quick and easy with some patients where the risk is felt to be minimal, whereas for other patients risk assessment and management turns into a very detailed undertaking making use of specialised assessment tools and may occur over a protracted period of time. This tiered approach2 of basic assessment at one end of a continuum to extremely detailed assessment at the other end will be well known to most clinicians and has been advocated as best practice in the UK. Depending on the level of detail required, the documentation will be quite varied.

Types of risk assessment

There are four major approaches to risk assessment but there is overlap within each.

Unaided clinical judgment

Unaided clinical judgment is exactly what it says. A history is taken, personality functioning is described, the mental state examined and demographic factors considered. Although unaided clinical judgment has importance, it has low inter-rater reliability and relatively low predictive value. A further problem with unaided clinical judgment is that it is also quite vulnerable to heuristic biases. Unaided clinical judgment is not recommended currently. For risk assessment of severe violence, a government committee in Scotland has stated that unaided clinical judgment cannot continue to be supported.3

Actuarial tools

Psychodynamic contribution

A psychodynamic contribution can add important information. The understanding of the risk behaviour for a patient can be enhanced using psychodynamic principles. For example, a violent patient may only attack other men of a certain age because they remind the patient of his father, or a patient with PTSD may only become suicidal on the anniversary of a violent assault. Further useful information may be elicited from feelings that the patient has towards different clinicians and the responses of clinicians towards the patient. Psychodynamic principles used in risk assessment are discussed further in Chapter 16.

Structured clinical judgment (SCJ)

The unaided clinical versus actuarial debate has led to the development of risk prediction instruments which adopt a combined approach and recognise the importance of both static (and dynamic) actuarial variables and the clinical/risk management items that clinicians normally take into account in risk assessments of individuals. The combined approach is called structured clinical judgment (SCJ) and represents a composite of empirical knowledge and clinical/professional expertise. Structured risk assessments act as aides-memoire and make sure that all relevant information is collected.5

Structured clinical judgment is a process which blends structured assessment of risk factors with clinical judgment, including the identification of the patterns of risk behaviours. On top of the usual history and mental state examination, the static and dynamic factors known to be of empirical relevance in the context of the patient’s illness are identified. This is then put together into a plan which addresses the risks. Structured clinical judgment is currently the recommended baseline modality of assessment. If the risk assessment is completed using a structured format, communication will be enhanced and be more transparent as the documentation will be clearly laid out and easily read. If all clinicians in a service use the same format, individual biases and personal opinions are less likely to intrude on the process.

Several structured instruments have been developed to assess risk in clinical contexts. These include the Historical/Clinical/Risk Management 20-item (HCR-20) scale6 for assessing violence and more recently a scale for the assessment of suicide risk developed by Bouch.7 These structured instruments are discussed in more detail in Chapter 18.

Advantages and disadvantages of SCJ using standardised rating scales

A difficulty with the use of structured instruments which include standardised rating scales is that best practice recommends they be validated. Unfortunately, for the general clinician seeing a wide variety of patients with differing risks, there is no one instrument which is currently available which has been validated. As yet, the literature has only generated one standardised assessment tool (the START)8 which attempts to cover a wide variety of risks, albeit with a rather thin evidence base currently. This is perhaps not surprising given the focus of research (mostly from forensic services) which tends to be on specific risks and the development of tools to help identify each risk.

If the tools are not used in a way that demonstrably adds something to standard clinical processes, then the time expended on paperwork will inevitably detract from the efficiency of service provision.9

Given this, it is perhaps not surprising that ‘locally developed, unstandardised, unvalidated schemes are often used in preference to standardised tools with demonstrated validity’.10

For the busy general clinician, risk assessment on a day-to-day basis may vary from assessment of violence with one patient to assessment of suicidality in the next and then to assessment of self-harm or assessment of harm from others. To utilise different standardised assessment tools for each of these patients when the risk may well turn out to be of minor significance would be pragmatically impossible and clinicians might be justified in complaining that the standardised assessment tools are too unwieldy. As Carroll (2007) comments when discussing the difficulties for general clinicians using standardised rating scales:

A pragmatic compromise for the general mental health clinician

The dilemma of how clinicians can practice SCJ has been considered carefully in the UK and best practice recommendations are, currently, that locally developed forms ‘should be designed with evidence-based principles in mind, stating clear and verifiable risk indicators’.12 This is a compromise allowing general clinicians to practise well without being encumbered with time consuming specialised rating scales. For the general mental health clinician:

the initial risk assessment exercise should consist of a structured process of more or less standard questions aimed at eliciting factors increasing the risk (and which will reflect the evidence base around the risk) and which assists clinical judgment. It could be called an aide-memoire or a framework. After the clinician addresses these standard questions, it will be possible to determine whether a more in-depth assessment is needed using existing, evidenced-based toolkits for the particular population.13

The major function of the model is as a ‘decision support tool’14 designed to assist the general clinician manage risk within the context of the illness. The framework incorporates the basic structures of standardised tools: focus on known static, dynamic and protective risk factors as well as a focus on management. The lists of empirical risk factors for each type of risk are separate to the model and can be updated as new research is published. The model is both an assessment and management tool and attempts to meet the following requirements:

• it has to be useful for clinicians and patients and facilitate clinical practice15

• it should not require too much in the way of training

• it should be short enough to be able to be completed on a regular basis by all mental health clinicians

• where possible, the document should be completed with the input of the patient and the final version should also be given to the patient (and family as appropriate)

• The model prompts for clinical information to help identify patterns of risk and to understand the function of the risk behaviour.

• The model focuses on static and dynamic factors and generates early warning signs, relapse indicators and proposes management for the risk within the context of the illness.

• The format is structured ensuring that all clinicians follow the same process no matter what the risk, and it covers the major areas of risk assessment.

• The model is a series of questions with prompts that are designed to focus the attention of the clinician on the key areas of risk assessment and management.

• When combined with a treatment plan which also focuses on early warning signs, triggers and relapse indicators, many of the items generated from the model can be ‘cut and pasted’ into the treatment plan.

• Because the model used is not a standardised rating scale, it only provides prompts for risk factors which may be relevant for each particular risk.

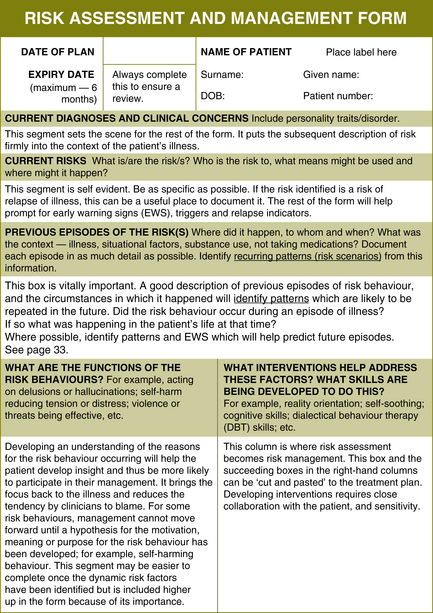

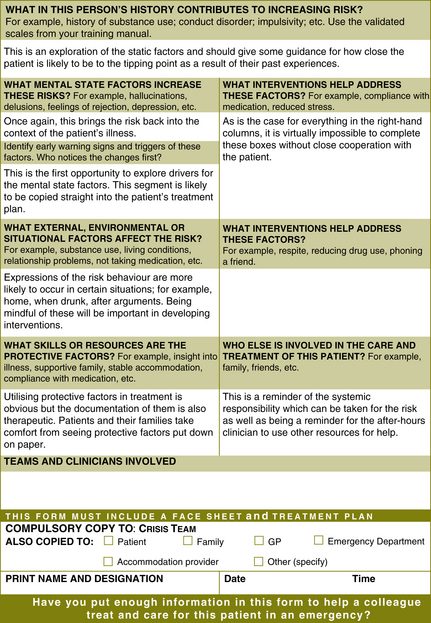

• By not having tick boxes for risk factors included in the risk assessment and management form (Figure 8.1), critical risk factors tend to be automatically identified as clinicians limit their focus to what is most important for their patient.

This model has changed many times over 6 years, has been refined and field tested in a mental health service of over 500 clinicians, and will continue to evolve. Feedback from a variety of sectors including Emergency Departments (EDs), general practitioners and crisis mental health teams has been of central importance in its continuing development. A major requirement in the development of this model has been the need to ensure that it integrates well with assessment and treatment documentation. It also needs to work within a tiered approach to risk.16 Documentation on risk within the clinical assessment can be ‘cut and pasted’ into this model. In a similar fashion the recommendations for interventions identified in this model can be cut and pasted into the treatment plan.

The model is weighted towards prevention and helping a clinician, who does not know the patient, manage an acute situation. In general mental health services this may be of more practical relevance. It avoids statements about level of risk. This is less common in tools derived from forensic services where the emphasis is more likely to be on prediction, level of risk and prevention in the longer term. The section of the model focussing on the function of the risk behaviour could be criticised for assuming that all risk behaviour is driven by frustration but in practice this is not always the case as it can also be coldly goal-directed and sometimes occurs in order to obtain a response from others — secondary gain. When this section has been left out of previous versions, the planning for possible interventions to manage frustration or secondary gain has often been forgotten to the detriment of the care of the patient. This section is sometimes very useful in picking up ‘signature risk signs’ specific to the patient; for example, a patient who has increased risk at the time of an anniversary.

If the risk documentation takes a structured narrative form, this allows the focus of inquiry to be directed and also allows risk factors to be contextualised and patterns identified.17 As a result, tick boxes have been excluded. The model allows for the level of risk to change over time and does not need updating with fluctuations of the clinical condition. If the risk plan is included in the overall treatment plan, it should not undermine in any way the overall thrust of treatment. (The treatment plan should include management of the identified dynamic risk factors.)

Examples of completed risk assessments/plans are in Appendix 3.

Static factors on risk assessment/plans

Most risk assessment/plans in general psychiatry do not document all the static factors. The model prompts for the major static risk factors only. If clinicians are developing a complete risk management plan for a patient — for example, a patient in a forensic unit with a risk of violence who is close to discharge — the risk management plan might include a detailed list of all the static risk factors of importance, especially psychopathy, and will describe the influence of the static factors on the current risk. The decision whether to document the static risk factors separately will vary from patient to patient. On the one hand, it is always useful to be able to see the static risk factors separately but on the other hand imposing this on staff means yet more filling out of forms and makes compliance less likely. Also, ‘forms irritate the people who have to fill them in’.18 The important point is to be able to use the static factors to help inform the management of the patient in the longer term.

Figure 8.1 is the complete model with commentary inserted into the boxes (in italics) where clinical information would usually be written. Many of the prompts have been taken from actuarial information. As clinicians get used to the format of the documentation, the prompts can be left out, which simplifies the form somewhat. When electronic health records are used, the prompts can be made to automatically disappear from the finished form. The form has been kept down to two A4 pages as anything longer than this seems to reduce the likelihood of clinicians completing it. When using this form, validated scales for the relevant risk should be utilised for reference.

The model, as printed over the next two pages, appears not to give sufficient room for information to be adequately documented. If there is more than one risk or if there have been several episodes of the risk behaviour previously, there would not be enough room in a hard copy

BOX 8.1 PRACTICE TIPS

• Whilst not semantically correct, clinicians seem to prefer the phrases which use the word ‘risk’ rather than the more correct phrase ‘adverse outcomes’.

• The box for previous episodes of the risks is frequently not big enough when the risk is that of violence or self-harm. When this form is used in an electronic version, the box expands accordingly.

• When used in an electronic health record, the right-hand column used for interventions usually disappears and becomes another horizontal row in the form. Some clinicians prefer to use the version with the interventions opposite the risk factors.

• Being able to cut and paste interventions from the risk management plan into a treatment plan is very useful.

version of this form. However, most clinicians utilise this documentation from a Microsoft Word template, or similar. The template can be copied into a separate patient file and information keyed directly into the template.

1 Maden A. Risk assessment in psychiatry. British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 56(2/3), 1996.

2 Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008 Rethinking Risk to Others in Mental Health Services. Final report of a scoping group. June 2008 Royal College of Psychiatrists College Report CR 150, June, p 38.

3 Scottish Executive. Report of the Committee on Serious, Violent and Sexual Offenders. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive; 2000.

4 Bouch J., Marshall J.J. Suicide risk: structured professional judgment. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2005;11:84–91.

5 Maden A. Standardised risk assessment: why all the fuss? Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27:201–204.

6 Webster C.D., Douglas K.F., Eaves D., et al. HCR-20: Assessing Risk of Violence (version 2). In Mental Health Law and Policy Institute. Vancouver: Simon Fraser University; 1997.

7 Bouch & Marshall, above, n 4.

8 Webster C.D., Nicholls T.L., Martin M.L., Desmarais S.L., Brink J. Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START): The case for a New Structured Professional Judgment Scheme. Behavioural Science and the Law. 2006;24:747–766.

9 Carroll A. Are violence risk assessment tools clinically useful? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41:301–307.

10 Higgins N., Watts D., Bindman J., Slade M., Thonicroft G. Assessing violence risk in general adult psychiatry. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2005;29:131–133.

12 Department of Health UK. Best Practice in Managing Risk. Principles and Evidence for Best Practice in the Assessment and Management of Risk to Self and Others in Mental Health Services. Document prepared for the National Mental Health Risk Management Programme, June 2007.. 2007.

13 Royal College of Psychiatrists, above, n 2.

14 McNeil D., Gregory A.L., Lam J.N., Binder R.L., Sullivan G.R. Utility of decision support tools for assessing acute risk of violence. Journal Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:945–953.

15 Royal College of Psychiatrists, above, n 2, Mullen, p 37.

16 Royal College of Psychiatrists, above, n 2, p 38.