1.1 Approach to the paediatric patient

Introduction

Who sees paediatric emergencies?

Some critically ill children will arrive in a more predictable fashion via ambulance and some preparation can occur to plan for their initial treatment. On the other hand, a child in extremis may well be rushed in from a family car, without any prior warning of their arrival. Systems of preparedness for these situations are critical for the immediate assessment and optimal early management of children by emergency department staff (see Chapter 2).

Identifying the potentially sick child

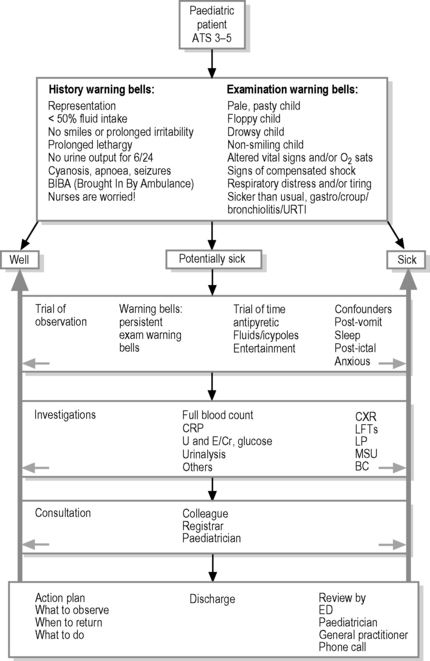

Of the vast number of children attending emergency departments, approximately 2–5% are classified as immediate emergencies (Australasian Triage Scale (ATS) 1 and 2) that require urgent assessment and management.1 Importantly, children can present with a less urgent triage category, but may rapidly deteriorate from evolving sepsis or airway compromise. The majority of paediatric presentations consist of less emergent problems involving a wide spectrum of injuries and illness. Of this group of paediatric patients there is a subset where the diagnosis is not immediately apparent. Thus, paediatric patients can generally be divided into three broad groups: the obviously well, the obviously sick or the potentially sick child. One of the major tasks for the emergency physician is to identify the ‘sick child’ from a large undifferentiated group of children who may present as potentially sick. It is by a ‘filtering process’ via history, examination, observation, investigation and consultation that one identifies the potentially sick child (Fig. 1.1.1). This group of patients includes: those children who have progressed to a severe form of a usually benign illness; those with early, subtle signs of a serious disease; or those who on initial assessment appear unwell, but require investigation to help rule out serious disease. It is often through observation of a child, that one is able to more accurately assess each of these possibilities.2 With experience, the ability to appreciate a ‘sick child’ improves; however, a good rule, particularly in the younger child, is, if in doubt, investigate, admit for a longer period of observation or seek the second opinion of a colleague.

Evolving illness in children

Due to differences in anatomy, physiology, development and psychology, children’s diseases are age specific, with serious illness often taking time to evolve.3 Many children present to an emergency department in the early stage of an illness and making a definitive diagnosis may require time. The clinical status of paediatric patients may also change rapidly. This can occur in response to prior trauma, evolving sepsis, toxin absorption or a seizure, and necessitate a change in the initial priority to receive treatment. The younger the child, the greater the potential for rapid deterioration as the early manifestations of a serious illness may be subtle and non-specific. One must be vigilant for the early signs of compensated shock such as tachycardia, decreased capillary refill, mottled skin, cool peripheries, decreased urine output, or drowsiness. Early detection and fluid resuscitation at this point may prevent hypotension in a child with evolving sepsis. Children with severe and deteriorating respiratory illness will manifest fatigue. It is the early recognition of children with serious illness or the potential to deteriorate that is critical to the timely initiation of effective treatment.2 An important principle in emergency paediatrics is to be proactive. One must be aware of the importance of regularly reviewing a child’s response to a given therapy, escalate treatment if required and be vigilant for subtle signs of deterioration.

Triage

Paediatric patients arriving in the emergency department should undergo triage according to standardised Australasian Triage Scale (ATS 1–5) so that they are seen in a prioritised fashion according to acuity. In mixed emergency departments where triage nurses may have had less paediatric experience, there has been a tendency to up-triage paediatric patients.1 The use of scoring systems for specific conditions or a Triage Observation Tool may be helpful in improving the reliability of triage in young children, who may present with non-specific symptomatology.4 A secondary nursing assessment should occur when the child is admitted to a cubicle, with further observations performed at the bedside, so that any change in condition can be detected early and acted on promptly. The senior doctor in the department should immediately be informed of children triaged as ATS 1 or 2 to direct timely management. In times of high workload, children with an ATS 3 may not be definitively assessed within 30 minutes and should have a senior doctor rapidly assess status and initiate therapy, if required. It may be necessary to modify normal triage systems when emergency department numbers are affected by surges in demand when significant influenza outbreaks or the like occur.

Fast tracking

Some initiation of treatment is appropriate during the triage process, such as the provision of analgesia for pain or an antipyretic in a child symptomatic of fever. It is important that children with pain are given early and appropriate analgesia or have injuries splinted when required. This will facilitate a more comfortable, reliable and expeditious assessment. The use of opiates, when required, will only enhance, rather than detract from the subsequent physician’s physical examination.5 The use of visual analogue scales such as the Wong–Baker faces may assist the assessment of a child’s response to analgesia. A process of fast tracking appropriate children with single limb injuries for an X-ray prior to definitive medical review may improve efficiency through the department. Febrile children who present with a rash, not clearly due to a viral exanthema or benign phenomena, should be fast tracked to be seen by a senior doctor to consider the possibility of meningococcaemia. It is useful to have documented management plans for children who may recurrently present to the department. This includes conditions such as complex children, brittle asthma, cyclical vomiting or recalcitrant seizures where a clear plan of management can expedite care by ED staff.

The paediatric approach

Age appropriate

The approach to any child in the emergency department is dictated by the child’s age and developmental level. It is useful to have a modified approach to suit newborns, infants, toddlers, preschoolers, school children and adolescents. An understanding of the concept of ‘the fourth trimester’ is useful in dealing with crying phenomena in the first months of life, which will often precipitate emergency department visits (see Chapter 1.2). A preverbal or developmentally delayed child won’t tell you of pain which has shifted to the right iliac fossa. An unwell 14-month-old clinging to mother may actively resist the initial attempts to be examined by a stranger. The absence of familiarity with a family or child that their family doctor may have may further impede the assessment of anxious children. When explaining procedures to children it is important to be age appropriate and above all honest. Never tell a child ‘you won’t feel a thing!’ prior to plunging a cannula through an EMLA anaesthetised cubital fossa. Rather, explain in age-appropriate terms what it may feel like and that it’s OK to cry.

Development appropriate

Infants particularly benefit from the constant presence of their parent in their visual field in order to avoid stranger distress and are often best examined in the parent’s arms. Neonates can be examined on the examination bed as long as they are kept warm. Toddlers, despite their evolving autonomy, will usually be less fretful if examined on a parent’s lap. It is a useful sign of illness or other cause to note when young children do not exhibit these normal stranger anxieties. The preschooler who enjoys a sense of play and imagination can usually be relaxed during an examination or procedure by storytelling or engaging in play with a toy. An anxious early school-aged child may respond to participation in the examination or being asked about school or other more favoured activities. Adolescents, on the other hand, need to be approached in a more adult fashion and should be offered confidentiality and the opportunity to choose whether their parents are present (see Chapter 30.1).

History

Children-specific issues

In younger children, certain symptoms are less specific. The report of vomiting in an infant may be due to meningitis, pneumonia, tonsillitis or urinary sepsis rather than gastroenteritis. The assessment of wellness or otherwise in infants can be more challenging due to their limited psychomotor activities. Indeed, their spectrum of normal behaviours involves sleeping, waking to cry or demand a feed, followed by a return to sleep. Hence, it is important to enquire into their feeding status and sleep/activity pattern as an indicator of compromise due to illness. One needs to carefully clarify what their current intake is compared to their normal breast- or bottle-feeding. An infant who is feeding less than 50% of normal has significant compromise. It is important to note the report of a young febrile child who remains lethargic and fails to smile or interact with parents. In the otherwise well-looking infant, who appears mottled, clarify with parents whether this may be usual for their child (i.e. physiological cutis marmoratum versus sepsis). In assessing young children with trauma, a thorough history of the timing and mechanism of injury, noting the child’s developmental capabilities, is paramount to detecting possible non-accidental injuries (see Chapter 18.2 on NAI).

Other useful information to cover in the paediatric patient history is shown in Tables 1.1.1 and 1.1.2.

| Presenting complaint |

|---|

| Pregnancy |

| Perinatal – delivery type, birth weight, need for resuscitation/special care nursery admission |

| Development – in a CNS problem, compatibility with injury mechanism |

| Immunisation status – need to clarify carefully |

| Previous illnesses/surgery/admissions/medications |

| Allergies |

| Infectious contacts/recent travel |

| Family history |

| Social history – family circumstances may influence a child’s disposition |

| Fasting status if relevant |

| Feeds – normal bottle or breast feeds for comparison |

Gentle, distraction, painful last

Index of suspicion

The routine methods of examination for signs of meningism in children are unreliable. Asking the child to look upwards at an object or down to their umbilicus is a more useful screen to detect nuchal irritation. The presence of photophobia is sensitivity to ambient light as most children will be offended by a torch light in the eyes. In children less than two years old, the early signs of meningism are often absent and threshold for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination adapted accordingly. Other significant but subtle features that may be missed on examination include persistent tachycardia or tachypnoea that is not clearly related to fever. One needs to be alert to the spectrum of stigmata of non-accidental injuries that may present to the emergency department (see Chapter 18.2 on NAI).

Abdominal examination

The abdominal examination needs to always conclude with the nappy area for otherwise occult torsions, hernias, skin problems and for stool examination, if present. The rectal examination in children is not routine and only performed with clear indication. One needs to be cognisant to maintain privacy and dignity, particularly when examining older children and adolescents. The examination of a child with possible sexual abuse is outlined in Chapter 18.1.

ENT last

Following any distressing procedure it is important to acknowledge bravery in a frightened child. Likewise, giving a child an honest, developmentally appropriate explanation of what to expect prior to any procedure, such as an IV insertion, is to be encouraged. This is best done immediately prior to the procedure so that an anxious child’s fears don’t escalate in the intervening period (Table 1.1.3).

| Other specific signs |

|---|

| Non-blanching rash – petechiae/purpura-sepsis |

| Bulging or full fontanelle – raised intracranial pressure |

| Bilious vomiting – bowel obstruction |

| High pitched cry – meningitis |

| Grunting – respiratory distress |

Observation

Observational variables

The general appearance of a child should include noting level of alertness, eye contact, activity, quality of cry, posture, interaction with the environment, irritability, colour, hydration, perfusion, general growth and nutrition, respiratory distress and presence of any unusual smell (e.g. ketotic). The lack of normal resistance to examination or a procedure expected of a child is an important observation to note. The sick child may make none of the resistance expected to examination or venepuncture. Observational variables have been shown to be more predictive of serious disease than historical information in young children.6 Likewise, clinical examination, considered alone, is a poor predictor of serious illness. Observation of a child needs to be performed as a separate process from the examination and may require a period of time for re-evaluation to detect disease progress. Researchers have used formalised scales such as the McCarthy Observation Scales to aid this assessment in febrile children.7 In the ED setting, discussion of a child with a colleague can be a rewarding aid to decision making.

Re-evaluate

This reinforces the power of observation. It allows time for a trial of fluids, reducing fever with an antipyretic, or seeing if a child responds to distraction. Subsequent re-evaluation of the child often allows one to differentiate whether a child is sick or well. The use of observation really allows one to identify the persistence of the initial abnormal examination findings. A child with intussusception may intermittently appear well and observation may be required to observe the clues to prompt the appropriate diagnostic investigation (Table 1.1.4).

When to investigate

Blood tests

Investigations may provide extra time for observation (by clinically reviewing the child!) and reassurance; however, if an investigation is performed and is abnormal, action must follow! The screening of urine in febrile young children is vital to detect occult urinary infection. In children less than 2 years old, dipstick analysis is inaccurate to exclude infection and microscopy must be performed to exclude pyuria. The appropriate techniques for obtaining urine are discussed in Chapter 16.4.

Management of paediatric patients

The urgency of management of children can be graded into the following categories:

The management of febrile young children is a large part of emergency paediatric practice. The current approach to those children without a clear focus is controversial and varies between institution and individuals. The two alternative approaches are risk- or test-minimising strategy (see Chapter 9). The current approach has been modified by the advent of pneumococcal vaccination. Certainly, it is reasonable, in a 3–36-month-old child, to be guided by clinical judgement alone with close planned review. If the child appears unwell, a sepsis screen is performed according to symptomatology. Neonates and small infants less than three months, where threshold for investigation is much lower, need to be approached according to departmental guidelines. Undifferentiated febrile children should be reviewed the next day and ongoing, until a definitive diagnosis is made or until the child returns to normal. Parents should be instructed to return to the department if their child deteriorates. The discharge action plan should give clear and understandable instructions on when to return. For example, in the febrile child, this should include: if child becomes more unwell, with decrease in intake to less than 50% normal, no urine output for six hours, or becoming drowsy beyond sleeping. Parents should be alerted to potential complications such as becoming limp, fitting or appearance of a rash, which warrant urgent review.

Factors influencing disposition

However, many other factors need to be considered in the disposition decision (Table 1.1.5). The threshold to admit a child is influenced by the child’s age, availability of appropriate follow up, assessment of parent’s ability to provide care and ongoing monitoring, the natural history of the illness and likelihood to deteriorate, social factors, comorbidity, distance from hospital, time of day, parental anxiety levels, availability of an early paediatric opinion, and the possibility that a child may be at risk. One needs to assess in a non-judgemental fashion the ability of the parents to carry out any ongoing treatment, and consider admission if there appears to be a need for ongoing support. When in doubt regarding whether or not to discharge a child, err on the side of caution. It may be prudent to consult, consider a period of observation in the emergency department, or admit the child to hospital.

Observation ward

Significant compromise from many childhood illnesses is often transient and will often respond rapidly to interventions commenced in the emergency department followed by a period of observation. Parents can often be reassured during this period of observation in hospital that their child has remained well and will respond to management strategies that subsequently can be continued at home. Studies have shown that many children admitted to hospital only require a limited period of subsequent in-patient therapy and are discharged in less than 24 hours.8 In a tertiary paediatric environment an effective way to manage these children is by admission to a short-stay observation ward. The emergency department needs to be appropriately resourced with staff to provide ongoing care and regular review of patients to expedite timely discharge. Conditions suitable for consideration of an observation ward admission will vary with local resources and may include asthma, croup, gastroenteritis, febrile convulsion, presumptive viral illnesses, non-surgical abdominal pain, minor trauma, post sedation recovery or ingestions.9 In mixed departments, without the facility of a short-stay ward, it is often appropriate to use the paediatric ward to admit patients who would benefit from a period of observation (see Table 1.1.5).

The role of the general practitioner in paediatric emergency management

Introduction

Management prior to hospital care

Some of the more common reasons for referral to the ED may include the following;

Developmental milestones

It is important to have an understanding of the major developmental milestones throughout childhood for the provision of care to paediatric patients. These can be rapidly confirmed by examination or parental enquiry. This allows one to use an appropriate age-modified approach in the child’s evaluation. Some specific behaviours, such as stranger anxiety in a 12-month-old, may challenge the assessment, so it is important to adapt the approach to these expected behaviours. Significant deviations from normal warrant consideration of paediatric referral. Useful early milestones are shown in the Table 1.1.6.

Growth

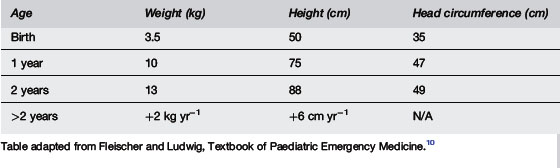

It is essential to measure a child’s current weight on every emergency department visit in order to accurately dose any therapeutic drug and to quantify recent weight loss. Where a child is critically unwell and unable to be weighed, estimation can be made via Broselow or other charts. Between the age of one and ten years an estimation of weight is 2 × (age + 4) kg. Standardised percentile growth charts are useful to confirm suspicion of failure to thrive or discrepancy in linear or cranial growth. The trend of growth plotted on a growth chart over time is more important than a single measurement. As a general rule, birth weight doubles by five months, and triples by one year. Newborns are often discharged from hospital in the first few days of life and may present in the first week to an emergency department. Following the expected initial weight loss, term babies should normally regain their birth weight by the end of the first week. Appropriate neonatal weight gain is an important index of wellness. Head circumference increases by 2 cm in the first three months, 1 cm in the next three months, followed by 0.5 cm per month thereafter (Table 1.1.7).

Immunisation

It is not the role of the emergency department to provide routine immunisations to children. It is useful, however, to clarify a child’s immunisation status with regard to the possibility of a particular infection such as epiglottitis, whooping cough or measles. Immunised children can, however, manifest a modified form of these infections. In children who are found to be incompletely or non-immunised, it is opportunistic to provide information regarding the normal vaccination schedule and refer to the local doctor or appropriate community facility for follow up (Table 1.1.8).

| Age | Vaccine |

|---|---|

| Birth | HepB |

| 2 months | DTP, OPV, Hib-HepB,7vPCV |

| 4 months | DTP, OPV, Hib-HepB, 7vPCV |

| 6 months | DTP, OPV, 7vPCV |

| 12 months | MMR, Hib-HepB, MenC |

| 18 months | DTP |

| 2–5 years | MenC |

| 4 years | DTP, OPV, MMR |

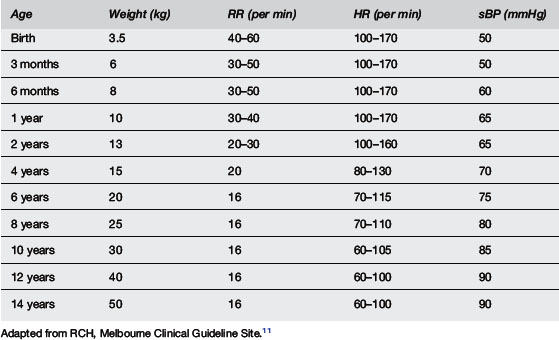

Vital Signs

It is necessary to interpret the vital signs according to the age of a particular child. A wall chart in the paediatric resuscitation area is a useful reference as a guide to these parameters. A good rule to remember is any child with a persistent respiratory rate >60 or heart rate >160 is definitely abnormal (Table 1.1.9).

Reflection on the thoughts of children and parents in ED

Thoughts on the emergency department through the eyes of a parent

1 Durojaiye L., O’Meara M. A study of triage of paediatric patients in Australia. Emerg Med. 2002;14:67-76.

2 Luten R.C. Recognition of the sick child. Problems in paediatric emergency medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1988;1-12.

3 Browne G.J. Paediatric emergency departments: Old needs, new challenges and future opportunities. Emerg Med. 2001;13:409-417.

4 Browne G.L., Gaudry P.L. A triage observation tool improves the reliability of the National Triage Scale in children. Emerg Med. 1997;9:283-338.

5 Browne G.J., Chong R.K.C., Gaudry P.L., et al, editors. Principles and practice of children’s emergency care. Sydney: McLennan and Petty. 1997:1-5.

6 Waskerwitz S., Berkelhamer J.E. Outpatient bacteraemia: Clinical findings in children under two years with initial temperatures of 39.5°C or higher. J Paediatr. 1981;99(2):231-233.

7 McCarthy P.L., Sharpe M.R., Spiesel S.Z., et al. Predictive observation scales to identify serious illness in febrile children. Paediatrics. 1982;70(5):802-809.

8 Browne G., Penna A. Short stay facilities. The future of efficient paediatric emergency services. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:309-313.

9 Scribano P.V., Wiley J.F., Platt K. Use of an observation unit by a paediatric emergency department for common paediatric illnesses. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001;17(5):321-323.

10 Fleischer G.R., Ludwig S. Understanding and meeting the unique needs of children. In Fleischer G.R., Ludwig S., editors: Textbook of Paediatric Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1993.

11 Royal Children’s Hospital. Clinical practice guidelines resuscitation: Emergency drug and fluid calculator. 2003. Melbourne, Australia, 2003. [ http://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/cpg.cfm?doc-id=5162 ]