Chapter 46 Approach to Diagnosis of Diffuse Lung Disease

• Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, proliferative bronchiolitis)

• Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis)

• Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (extrinsic allergic alveolitis)

This problem has been partially addressed by the reclassification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias by a joint American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) international consensus committee, discussed in detail in Chapter 47. However, the term cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis (CFA) continues to cause difficulties. As defined in the ATS/ERS reclassification, CFA is strictly synonymous with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The diagnosis of IPF/CFA now requires the presence of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) at surgical biopsy or typical appearances on HRCT, in association with a compatible clinical picture. This represents a radical change; in historical series, various disorders presenting with a clinical picture of IPF were grouped together as IPF/CFA. The entity of “clinical CFA syndrome” is still necessary for epidemiologic studies but should not be viewed as a final diagnosis in clinical practice.

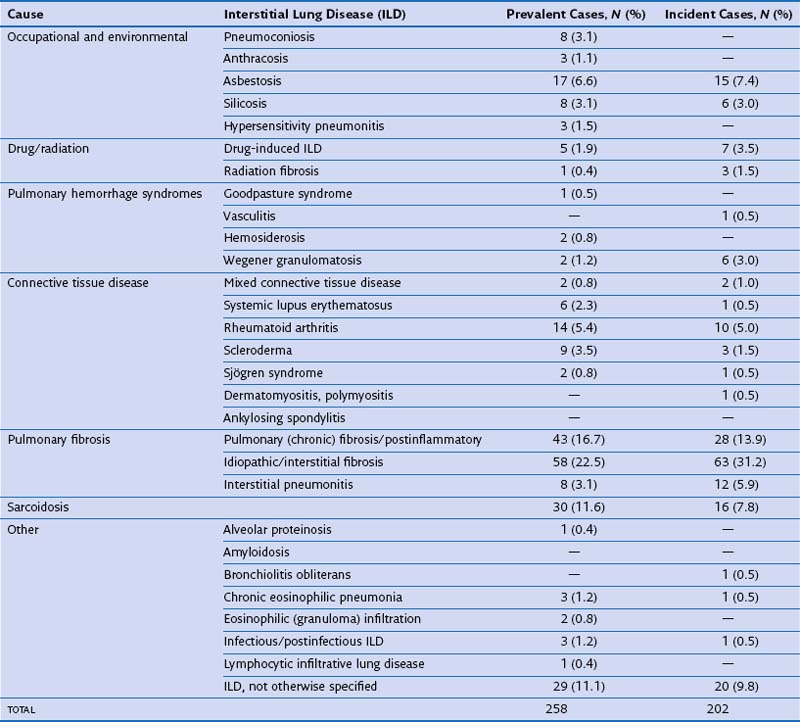

In routine practice, a simplified pragmatic approach to diagnosis of DLD is essential; consideration of a checklist of the more common diseases is often useful. The classification of DLD by their disease burden was addressed most definitively in a study from Bernalillo County, New Mexico, in which the incidence and prevalence of individual DLDs was quantified using a variety of methods (Table 46-1). New cases were estimated to occur in 32 : 100,000 years in males and 26 : 100,000 years in females; thus, although less common than lung infection, malignant disease or obstructive airways disease, the DLDs are responsible for a considerable disease burden. More recent evidence shows an increase in the prevalence of DLD, especially IPF, which inevitably means that the burden of disease has increased further in the previous one to two decades. Moreover, the workload for the respiratory medicine physician is disproportionate because the diagnosis of individual DLDs is often uncertain, despite more intensive investigation than is generally required in obstructive airways disease, malignancy, or chronic lung suppuration.

Initial Clinical Evaluation

Clinical History

The identification of an underlying cause is the single most important contribution made by clinical evaluation. Table 46-2 provides a checklist of the more important causes of DLD. A careful occupational history is essential and should include details of all previous occupations, including short-term employment. Asbestos exposure is often extensive in railway rolling-stock construction, shipyard workers, power station construction and maintenance workers, naval boilermen, garage workers (involved in brake lining), and other occupations in which asbestos exposure is overt; generally, workers in these occupations are well aware of their asbestos exposure. However, other workers, including joiners, electricians, carpenters, and construction workers, who handle asbestos in the form of roofing and insulation material, are often unaware of significant exposure. Other occupations associated with DLD include coal mining (coal worker’s pneumoconiosis), metal polishing (hard metal disease), and sandblasting (silicosis).

Table 46-2 Frequently Encountered Diffuse Lung Diseases with Identifiable Underlying Cause

| Cause | Differential Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Occupational-related or other inhalant–related | |

| Inorganic | |

A detailed drug history is also essential. The drugs most frequently causing DLD are probably amiodarone, methotrexate (at doses used in CTD), and antineoplastic agents, especially bleomycin. However, a wide variety of other agents (>200 at present) cause DLD, although often in only a small number of patients, and the list increases yearly. Fortunately, an international website is now devoted to drug-induced lung disease (www.pneumotox.com), through which all medications should be routinely checked in patients with DLD.

Diagnostic Procedures

High-Resolution Computed Tomography

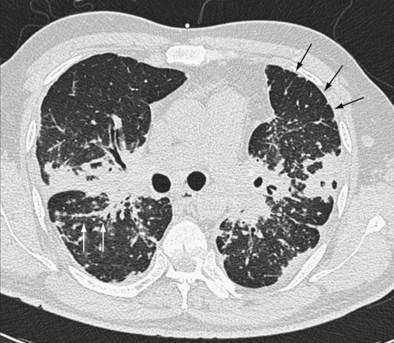

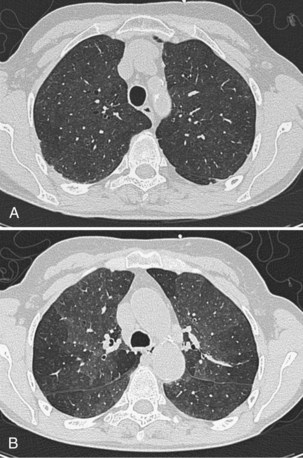

The distinction between predominantly inflammatory and predominantly fibrotic disease can generally be made with reasonable confidence from HRCT. Anatomic distortion and reticular abnormalities are strongly indicative of irreversible fibrotic disease, and this is invariably true of honeycomb change (Figure 46-1). Consolidation is usually reversible, although it may occasionally represent dense fibrosis, especially in sarcoidosis. Ground-glass attenuation is often more difficult to interpret. In early work, this HRCT sign was shown to identify a substantial increase in the likelihood of significant inflammation, especially in the absence of concurrent reticular abnormalities. However, it is now clear that ground-glass attenuation denotes fine fibrosis in many cases, especially in sarcoidosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, in which ground-glass attenuation is the cardinal HRCT feature (Figure 46-2). Traction bronchiectasis is a key HRCT discriminator because it invariably indicates underlying fibrosis. Thus, reversible inflammatory disease is likely only when ground-glass attenuation is not associated with traction bronchiectasis or admixed with reticular abnormalities.

A wide range of HRCT profiles encompassing the distribution and pattern of DLD strongly suggests individual diseases. Box 46-1 summarizes the cardinal findings in common DLDs. As with its other applications, it is essential that HRCT findings be integrated with the pretest diagnostic probability, distilled from the history, clinical signs, previous natural history, or treatment course and the investigative findings, especially chest radiography, pulmonary function tests, and serology for autoimmune disease and environmental antigens. The role of HRCT in diagnosis is critically dependent on the presence or absence of a likely cause. In patients with appropriate environmental antigen or drug exposures (hypersensitivity pneumonitis, pneumoconioses, drug-induced lung disease), malignant disease (lymphangitis carcinomatosis), clinical or serologic evidence of CTD, or a heavy smoking history (Langerhans cell histiocytosis, RBILD), the diagnostic weighting required from HRCT can be reduced. In these contexts, HRCT appearances that are merely compatible (and not classic) often allow a sufficiently confident diagnosis to obviate diagnostic surgical biopsy.

Box 46-1

High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT) Features of Select Diffuse Lung Diseases (DLDs)

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Lower zone, subpleural predominance, maximal posterobasally, predominantly reticular pattern with associated honeycombing.

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: Two typical appearances:

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia: Ground-glass attenuation, sometimes diffuse, sometimes basal and peripheral–centered, frequent associated fibrotic cysts with anatomic distortion and traction bronchiectasis.

Acute interstitial pneumonia: Widespread ground-glass attenuation admixed with features of fibrosis, usually with air space consolidation and occasionally with emphysema.

Respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease: Patchy ground-glass attenuation, poorly defined centrilobular nodules, occasional mosaic attenuation, prominent bronchial wall thickening.

Sarcoidosis: Highly variable; nodules distributed along bronchovascular bundles, interlobular septae, and subpleurally, including the fissure; ground-glass attenuation that may represent either inflammation or fine fibrosis; reticular abnormalities representing fibrosis; distortion most often in upper zones with posterior displacement of upper lobe bronchus; air trapping; associated hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis: Widespread ground-glass attenuation, often containing poorly defined centrilobular nodules, admixed with areas of “black lung” (mosaic attenuation), representing air trapping and enhanced on expiratory HRCT.

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: Bilateral patchy consolidation, subpleural and predominantly basal in most cases; occasional peribronchial distribution; associated, often-sparse nodules up to 1 cm in diameter.

Constrictive bronchiolitis: Patchy areas of hyperlucency enhanced on expiration, which may not change in cross-sectional diameter on full expiration; associated bronchiectasis and bronchial wall thickening.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Bizarre cyst shapes and associated nodules throughout the lung fields but sparing costophrenic angles and tips of lingula and middle lobes; associated emphysema often seen.

Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis: Homogeneously distributed, thin-walled parenchymal cysts, varying from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter; associated with retrocrural adenopathy, pleural effusion, thoracic duct dilation, pericardial effusion, and pneumothorax.

1. The first step is to determine whether HRCT abnormalities are predominantly fibrotic, based on the presence of honeycombing, reticular abnormalities, anatomic distortion, or in patients with prominent ground-glass attenuation, the presence of traction bronchiectasis.

2. If disease is fibrotic, as in a large majority of cases, the next important question is whether HRCT findings are typical of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. As stated in the 2011 American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) recommendations, IPF can be diagnosed confidently on HRCT when there is honeycombing with minimal ground-glass attenuation in a predominantly basal and subpleural distribution. It is logical to focus on IPF because it is the most prevalent idiopathic fibrotic disease among patients in whom the diagnosis is not obvious from clinical and chest radiographic findings (most cases of sarcoidosis are diagnosed without recourse to HRCT) (Figure 46-3). Further, IPF has a much worse prognosis than other fibrosing processes and therefore is the most important diagnosis to confirm or exclude from the outset. It is now known that HRCT appearances considered typical of IPF by experienced thoracic radiologists have a PPV greater than 95%.

3. If appearances are not typical of IPF, the five most important differential diagnoses (based on prevalence in routine practice) are (a) IPF with atypical HRCT appearances, (b) sarcoidosis, (c) nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, (d) hypersensitivity pneumonitis (with the antigen unknown), and (e) the fibrotic sequelae of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Among these, IPF with atypical HRCT appearances is the most prevalent disorder in most populations; up to 30% of IPF patients have atypical HRCT features. Atypical IPF is especially likely when HRCT appearances are not typical of any of the other four disorders (b-e).

The weighting given to HRCT in the diagnosis of DLD varies from case to case but can usefully be considered in three categories. In some patients, HRCT appearances are virtually pathognomonic; this includes many cases of IPF, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, sarcoidosis, and lymphangitis carcinomatosis. Often, HRCT findings are diagnostic when combined with clinical information. A good example is the combination of widespread ground-glass attenuation (often with poorly defined centrilobular nodules) in combination with mosaic attenuation, which may be strongly indicative of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in nonsmokers with a compatible exposure history but may also represent RBILD in smokers (Figure 46-4). Third, even when not conclusive alone, HRCT may be invaluable when considered with diagnostic surgical biopsy. The histologic entity of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) is found in a variety of clinicoradiologic contexts, including entities overlapping clinically with IPF, fibrosing organizing pneumonia, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis; HRCT evaluation is key to distinguishing among these variants.

Integrated Diagnosis in Diffuse Lung Disease

This decision should be made pragmatically and not by protocol. The value of a specific diagnosis in diffuse idiopathic lung disease is that the clinician is informed of the probable natural history and the likelihood that treatment will play a useful role. From these considerations, the optimal approach to monitoring disease during follow-up usually becomes apparent. Thus, the essential purpose of pursuing a diagnosis is to identify probable disease behavior with and without treatment. Broadly, with occasional exceptions, longitudinal disease behavior in DLD can be subdivided into five patterns (Table 46-3). When a patient can be subclassified confidently into one of these groups, invasive investigation will often add little to short-term and long-term management. Three strands of information are of particular value in making these distinctions: the underlying cause (if any), a morphologic assessment using HRCT (and histologic evaluation in select patients), and observed longitudinal disease behavior.

Table 46-3 Most Common Patterns of Longitudinal Disease Behavior in Diffuse Lung Disease (DLD) with Select Underlying Diagnoses*

| Pattern | Select Diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Self-limited inflammation |

* May appear in several categories; excluding idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (see Table 46-4).

These principles apply especially to the most common presentation of nongranulomatous idiopathic DLD: the cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis (CFA) clinical syndrome. In previous decades, underlying histologic appearances have tended to be lumped together, but the recent ATS/ERS reclassification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias has provided a framework for the separation of a number of disease entities with strikingly diverse natural histories and treated outcomes (Table 46-4). In evaluation of biopsy diagnoses in the 1980s of “cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis” in patients presenting with the CFA clinical syndrome, an alternative histologic diagnosis associated with a much better observed outcome was evident on review in more than 50% of cases. The ATS/ERS classification system is logical and pragmatic because each entity tends to fall into a particular category of longitudinal disease behavior, although a degree of overlap is inevitable. Thus, when a confident noninvasive diagnosis is unattainable in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, surgical biopsy should always be considered.

Table 46-4 Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias*

| Clinicopathologic Diagnosis | Likely Longitudinal Behavior |

|---|---|

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis/cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis | Inexorably progressive fibrosis |

| Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) | Cellular NSIP: self-limited or major inflammation |

| Fibrotic NSIP: stable or progressive fibrosis | |

| Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia | Self-limited or major inflammation |

| Desquamative interstitial pneumonia | Self-limited or major inflammation |

| Respiratory bronchiolitis–associated | Self-limited inflammation interstitial lung disease |

| Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia | Self-limited or major inflammation |

* American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) consensus classification, with most common patterns of longitudinal behavior associated with individual diagnoses.

Treatment

1. A policy of careful observation without immediate intervention is appropriate if the pattern of behavior is one of self-limited inflammation or stable fibrotic disease.

2. When inflammatory disease is viewed as intrinsically dangerous because of disease severity or is admixed with progressive fibrotic disease, high-dose initial therapy is necessary, with careful definition of the optimal treatment status, as determined by clinical features, imaging, and pulmonary function tests. In the longer term, after initial treatment, best management consists of establishing the minimum level of treatment that serves to preserve the initial gains. However, the specifics of any follow-up treatment protocol depend on the amplitude of the response and the severity of residual irreversible disease.

3. In purely fibrotic diseases, in which stabilization is a realistic long-term goal, initial high-dose corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy would not be expected to achieve regression of disease. The key to management lies in finding “civilized” long-term regimens, with toxicity levels acceptable to patients, which prevent further disease progression.

4. In inexorably progressive fibrotic disease, effectively equating with IPF or an IPF-like treatment course in other fibrosing disorders, a “civilized” nontoxic approach is paramount. Delaying disease progression is a realistic goal in some patients, but not at the cost of major toxicity. The importance of distinguishing between IPF and other fibrosing disorders is that in non-IPF diseases, it may be justifiable to take risks with treatment toxicity to attempt to stabilize disease.

5. A final diagnosis is not possible in many patients. The most likely scenario, based on disease prevalence, is probable IPF, but possible fibrotic NSIP or hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Guideline statements written for “definite IPF” do not address this frequent conundrum, and in many elderly patients with major comorbidity or severe lung disease, a surgical biopsy is not practical. In the absence of guideline statements, arguably the most frequent error is to miss an opportunity, and management should be determined by the most optimistic outcome scenario. If NSIP or hypersensitivity pneumonitis is a realistic possibility, a more aggressive approach, as indicated by those diagnoses, is appropriate, even when IPF is clearly the most probable diagnosis.

Controversies and Pitfalls

Decision to Perform Biopsy

1. A biopsy is an absolute requirement if a logical management plan can be constructed only with this information, if disease is overtly dangerous, and if there is a real risk of worsening the situation with the wrong treatment approach. Clearly, it is the duty of the physician in this scenario to persuade the patient to undergo the lung biopsy.

2. A biopsy would make management somewhat more precise and might provide benefits in terms of diagnosis and management in the longer term. However, it would be possible to construct a rational, reasonably definitive treatment approach without this information, but without less confidence. The patient can then be informed that a biopsy is strongly recommended, but that the physician could, with some misgivings, construct a logical treatment plan without this information if the patient does not accept the recommendation.

3. The arguments for and against a biopsy are finely balanced (“50/50 call”). In this case, if the patient has strong views as to whether or not to undergo the procedure, the decision is no longer finely balanced.

4. On balance, a biopsy is not needed, and the physician can construct management without this information. However, a biopsy might provide earlier information on the likely outcome, and the patient needs to be informed that a biopsy might therefore reduce uncertainty, while not changing management. Severe anxiety caused by uncertainty is a valid indication for an invasive diagnostic procedure, and it is appropriate for the patient to choose to undergo the procedure for that reason alone.

5. A biopsy should not be performed because the diagnosis is already secure, based on noninvasive data, or because the risks of the procedure are unacceptably high.

American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:646–664.

American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society. ATS/ERS international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277–304.

American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/Japanese Respiratory Society/Latin American Thoracic Society Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824.

Bertorelli G, Bocchino V, Olivieri D. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Eur Respir Monogr. 2000;14:120–136.

Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, Sobonya RE. The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:967–972.

Epler GR, McLoud TC, Gaensler EA, et al. Normal chest radiographs in chronic diffuse infiltrative lung disease. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:934–939.

Flaherty KR, Thwaite EL, Kazerooni EA, et al. Radiological versus histological diagnosis in UIP and NSIP: survival implications. Thorax. 2003;58:143–148.

Flaherty KR, King TEJr, Raghu G, et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: what is the effect of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:904–910.

Hunninghake GW, Zimmerman MB, Schwartz DA, et al. Utility of a lung biopsy for the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:193–196.

Latsi PI, Du Bois RM, Nicholson AG, et al. Fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: The prognostic value of longitudinal functional trends. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:531–537.

Nicholson AG, Colby TV, du Bois RM, et al. The prognostic significance of the histologic pattern of interstitial pneumonia in patients presenting with the clinical entity of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2213–2217.

Utz JP, Ryu JH, Douglas WW, et al. High short-term mortality following lung biopsy for usual interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:175–179.

Wells AU. High resolution computed tomography in the diagnosis of diffuse lung disease: A clinical perspective. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;24:347–356.