Chapter 7 Application – Integrative healthcare

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a move towards the integration of CAM into mainstream healthcare. The emergence of new societies, academic chairs, forums, publications, referral networks, integrative clinics and centres of integrative healthcare are testament to this claim. Yet despite the level of progress in this area, few have questioned whether such a shift is appropriate or acceptable, and even fewer have explored how or why this approach should be implemented. This chapter will address these concerns by examining the merits and limitations of integrative healthcare and, further to this, highlight how these strengths may help to improve some of the shortfalls of a conventional system of care; it will also address the drawbacks of independent practice. But before addressing these issues, the term ‘integrative’ needs to be understood.

Defining integrative care

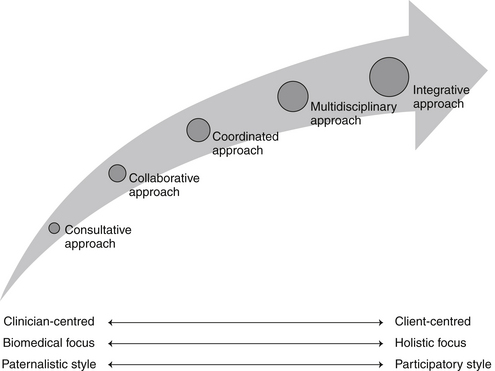

Over the past few decades there has been a shift in the way healthcare has been delivered, from the traditional consultative, paternalistic and independent practice model, to the multidisciplinary approach and, more recently, to the integrative healthcare model. As one moves to the right of this consultative–integrative healthcare spectrum (see Figure 7.1), it is clear that these approaches become more holistic, complex and patient-centred as practitioner autonomy, hierarchy and reliance on the biomedical model decrease.1 What this spectrum fails to differentiate, though, is integrative medicine from integrative healthcare, which are distinctly different, non-interchangeable approaches to care.

Integrative medicine is defined by Rees and Weil,2 for instance, as ‘practising medicine in a way that selectively incorporates elements of complementary and alternative medicine into comprehensive treatment plans alongside solidly orthodox methods of diagnosis and treatment’. What this definition implies is that integrative medicine is professionally exclusive because it applies only to the uptake of CAM by biomedical practitioners. By failing to consider other aspects of assimilation, such as the inclusion of CAM practitioners within mainstream settings, such a term holds little relevance to CAM practice. A more appropriate and inclusive term is ‘integrative healthcare’.

Integrative healthcare is defined as a multidisciplinary, collaborative and patient-centred approach to healthcare in which the assessment, diagnostic and treatment processes of alternative and conventional medicine are equally considered.3 This clinical approach also ‘combines the strengths of conventional and alternative medicine with a bias towards options that are considered safe, and which, upon review of the available evidence, offer a reasonable expectation of benefit to the patient’.4 Put simply, integrative healthcare is a comprehensive and holistic approach to healthcare in which all health professionals, including biomedical and CAM professions, work collaboratively in an equal and respectful manner, to safely and effectively meet the needs of the patient and the community.

Conventional system of healthcare

Existing systems of healthcare are diverse and complex but are generally based on a similar purpose, that is, the treatment of disease and infirmity.5 A more effective system of healthcare also needs to focus on preventing disease and promoting wellbeing,5 as well as providing care that is individualised, holistic and patient-centred. Given the reductionist, fragmented, standardised and disempowering treatment often provided in conventional systems of healthcare at present,6 particularly in secondary care settings, it is necessary that these systems be carefully evaluated and subsequently improved.

These systems of healthcare can be evaluated in terms of acceptability, efficiency and equity.7 Acceptability for instance, refers to patient, community and provider acceptance of the system. System inefficiencies, quality of care, personal experience, beliefs and preferences are all likely to impact on this outcome.

The service, administrative and economic efficiencies of the healthcare system, or performance of the system, is influenced by a number of factors, such as skill mix, funding, resource allocation, infrastructure, system priorities, adaptability to change and outcomes of care.7 Even though many healthcare systems have attempted to improve system efficiency through the introduction of casemix funding (an outcome-based funding model),8 there are still ongoing issues relating to continuity of care, unavoidable costs, evaluation of service outcomes, adaptability to system level changes and the balance between medical and non-medical services.7,8

The final component of system evaluation is equity, which is concerned with indiscriminate access and outcomes of healthcare services.7 Even though universal and equitable access to healthcare may be improved through the provision of national subsidy schemes, such as the Australian Medicare system, in most cases these public programs only subsidise the delivery of medical, hospital and laboratory services.5,9 One exception to this is the Australian Medicare-funded enhanced primary care program, which allows eligible persons to gain access to a limited number of allied health services, albeit via referral from a general practitioner. The subsidisation of pharmaceutical agents through the pharmaceutical benefits scheme (PBS) is another long-standing national subsidy program,9 although, once again, it only applies to specific medical treatments.

These examples illustrate that in Australia at least, the mainstream system of healthcare has been designed to perpetuate the interests of certain key stakeholders, such as medical practitioners and pharmaceutical companies.5 The exclusion of other pertinent health services (such as naturopathy and massage therapy) and products (including most herbal medicines and nutritional supplements) from these subsidisation schemes indicates that this system is, by definition, unequitable. The following paragraph exemplifies this point further.

In Australia, health consumers have access to a wide range of CAM services, yet only a proportion of these services can be financially reimbursed through private insurance companies and none of the products prescribed by CAM practitioners are eligible for reimbursement. For consumers with chronic or complex care needs, there is limited access (i.e. maximum of five allied health services per year) to publicly funded CAM services, specifically, chiropractic and osteopathy. Thus, for the many individuals who wish to access CAM services but are uninsured, have an acute complaint or have long-term care needs, they will have to pay for these services out of pocket. According to a recent Australian survey of CAM consumers, these out-of-pocket expenses can range from AUD$1 to AUD$650 per month (mean = AUD$21.23) per user. This translates to AUD$1.3 billion per annum at the national level.10

The escalating cost of maintaining the current system is unlikely to be efficient, cost-effective or sustainable in the long term.5 Measures that improve the efficiency, acceptability and equity of existing systems of healthcare need to be implemented so that the needs of all individuals can be better met.5 These strategies also need to offer a significant cost–benefit to the system. One strategy that may fulfil these requirements is the development of an integrative system of healthcare.

Movement towards integration

Over the last decade, there has been rising interest and increasing use of natural medicines and complementary practitioner services. This trend not only applies to consumers, but also to practitioner groups: orthodox clinicians now use and endorse a wide range of complementary therapies.11,12 The scientific community is also pushing healthcare towards a more integrative approach,13 with a number of integrative clinics, hospitals and academic centres now available across the globe, and pharmacies and pharmaceutical companies now selling a range of conventional and complementary medicines. Evidence also suggests that CAM practitioners are being accepted as legitimate health service providers.14 One could argue that the legitimisation of CAM services, together with the integration of these services into mainstream care, may be influenced by the increasing biomedical content and evolving curricula of undergraduate CAM courses, the closer alignment of these courses with the scientific paradigm and subsequent improvements in biomedical language proficiency among CAM practitioners, but the impetus for these changes in practice remains unclear, although many factors have been proposed.

The shift towards CAM could be explained in part by mainstream medicine’s inability to adequately address a number of patient needs,15–17 including the need for respect, holism, choice, autonomy and time. The erosion of client–practitioner relationships, the dependence on invasive technologies and the primary focus on disease might also contribute to the move away from orthodox practice.17 So, a change in patient needs and beliefs may be a factor driving the increasing use of CAM.16,18

Individuals with chronic and life-threatening conditions may also turn to CAM in order to find a solution to their problem. One reason why these patients may try CAM is that conventional practice, and the system it is situated in, does not allow for high-quality prevention or treatment of chronic disease.19–23 Key stakeholders may need to consider an integrative model of practice in order to address the shortfalls of both the current system of healthcare and the medical model.17

Medical pluralism, or the utilisation of more than one form of healthcare, can increase the number of interventions made available to patients and, in turn, provide the client with a number of different treatment perspectives. As opposed to the paternalistic and universalistic model of healthcare that currently exists, the more pluralistic and individualised system of integrative care may foster collaboration between CAM services and mainstream practitioners, improve client outcomes and more effectively meet the needs of patients.21 At present, however, the existing system of healthcare is the antithesis of pluralistic.15

The right to be informed about a range of therapeutic options from a variety of disciplines is a right of every individual. Yet, since most conventional clinicians are not sufficiently knowledgeable about CAM and preventative healthcare11,20,24–26 and many CAM practitioners might not be familiar with the myriad orthodox treatment approaches,27 a number of clinicians may not be equipped to inform patients about an appropriate range of therapies. Practitioner bias or lack of knowledge about other modalities could also deprive patients of suitable treatment options and, in effect, compromise the patient’s ability to make an informed decision about their care.24 Since practitioners have an obligation to inform patients about treatments that are well supported by evidence,28 strategies that facilitate this process are in the best interests of the client. The inclusion of CAM content within medical degrees and the increasing biomedical content within CAM courses is a critical step towards addressing this problem.

Problems with integration

In spite of the push towards an integrative system of healthcare, many issues need to be considered before accepting this approach (see Table 7.1). The first of these relates to the different paradigms of CAM and orthodox medicine. Since integrative healthcare is not just about adding therapies to a discipline, but is also about accepting a different mindset,15 this is of some concern, as many practitioners who are well trained and experienced in their respective therapies may be unwilling to accept new healthcare philosophies or new challenges to convention.29 In fact, conventional clinicians who simply choose a few isolated therapies to incorporate into their practice may be seen ‘as orthodox biomedical cherry picking from the complementary field, [in order] to supplement conventional treatment’.30 The same principle also applies to CAM practitioners who choose to adopt complementary therapies for which they have no formal training, for example, a chiropractor choosing to dabble in herbal medicine or a naturopath dabbling in acupressure. In either case, ignoring the philosophical foundations of a treatment may deem the approach as simply another tool and not an independent therapy in its own right.

Table 7.1 Challenges facing the integrative healthcare movement

| Interprofessional issues |

Clinicians choosing to incorporate CAM modalities into clinical practice need to be mindful of the level of competence required to deliver these therapies, as some practitioners may be adopting new modalities that they are not well equipped to use.31 This is particularly important, as adequate training in CAM is critical to the safe and effective delivery of CAM.15 The rate of adverse events per year of full-time traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practice by 1278 non-medical practitioners (NMP) and 458 medical practitioners (MP) who practised TCM, for example, was 1/1009 consultations and 1/368 consultations respectively (p<0.001).32 The authors attributed these differences to the inadequate training of MPs, with the average length of TCM training among MPs approximating 8 months, compared with 43.6 months among NMPs.33 This disparity in MP and NMP training has also been identified elsewhere.33 There is related concern that the therapies being integrated into clinical practice may not be supported by clinical evidence. Opponents of integrative care, for instance, argue that complementary therapies do not belong in orthodox medical settings because of scientific divide between the two settings.34

However, given that many conventional medical practices (including various surgical techniques (e.g. circumcision, tonsillectomy) and diagnostic methods (e.g. X-rays, screening tests)) have not been tested to the level expected of CAM,35,36 that is, under double blind randomised placebo-controlled conditions, these arguments about the efficacy of treatments are not well founded. Instead, these concerns about the evidence-base of CAM may just be a smokescreen for other political or philosophical issues.37

Other factors impeding the assimilation of CAM into conventional healthcare settings relate to cost-effectiveness, funding, safety, financial reimbursement, infrastructure, and practitioner credentialling.38,39 Unless these constraints are addressed, access to appropriate treatment options could be delayed. Furthermore, by failing to accept integrative care, clinicians may deny patients safe and effective treatments,14 and, in effect, provide care that may not best meet the needs of the client. The continuation of sole practitioner practice models (where practitioners work independently of one another), for instance, may only serve to perpetuate this problem and further sustain the marginalisation of CAM practitioners.

Merits of integration

The integration of credentialled CAM services into healthcare settings traditionally dominated by orthodox medicine (such as hospitals, rehabilitation centres and superclinics) holds many benefits for consumers and practitioners (see Table 7.2). One of these merits is the capacity to ‘bring together the strengths and to balance the weaknesses inherent in [the] different systems of healthcare’,27 and, in effect, provide a more favourable and complete system of care. CAM may also provide alternatives to treatment when conventional practice can no longer offer a solution37,40 or when medical treatment is ineffective or harmful,17 in, for example, the management of chronic pain, psoriasis, irritable bowel syndrome and menstrual complaints. In essence, integrative practices may increase healthcare choices, improve treatment outcomes and enable patients to more effectively navigate through the range of available treatment options.41

The fragmented and incomplete care provided by some professions may drive a number of practitioners to use CAM modalities or products in order to address the shortfalls of their discipline.42 Integrating CAM philosophy into orthodox practice (including the principles of holism, client-centredness, illness prevention and wellness optimisation) may also provide practitioners with the means to deliver individualised healthcare31 that is more holistic and less fragmented.43

Although the delivery of CAM services can be time and labour intensive, it is in many ways more cost-effective than the delivery of conventional care,37,44 which leads to the argument that the inclusion of CAM practitioners within mainstream healthcare settings could generate substantial cost savings to the health service. This could be attributed in part to a reduction in the duplication of services or the use of less costly equipotent interventions. While earlier reports have found CAM to be no more cost-effective than conventional care, more recent evidence suggests otherwise.45,46 As well as saving costs, an integrative approach to healthcare may also increase patient satisfaction.47,48 One possible explanation for these improved outcomes may lie in the focus of care, with integrative healthcare being more client-centred than conventional care,29,49 and, as a result, more likely to address patient needs.48

Models of integration

In terms of complexity and skill mix, existing frameworks for the delivery of integrative medicine and/or integrative healthcare vary significantly. The level of integration reported in these models is also diverse, ranging from the basic uptake of selected CAM interventions by orthodox practitioners, to non-collaborative multidisciplinary clinics or networks, to the more complex integration of professional CAM services within a large collaborative interdisciplinary team. An integrative system of healthcare that would be of most benefit to patients is one that provides consumers with greater access to a full range of qualified practitioners and does not surrender practitioner or patient autonomy. A suitable model of healthcare should also inform patients about all appropriate treatment options, offer options in a prioritised manner and be focused on prevention, healing and health creation.15,18 The model should also be holistic, promote evidence-based practice and be mindful of all individuals in a client’s milieu.15

Leckridge50 reports on four possible models of integrative healthcare: the market, regulated, assimilated and patient-centred models. The market model enables patients to access any healthcare product or service they desire. While such a model promotes freedom of choice, it is often chaotic, costly and unintegrated. A similar framework is the regulated model, although in this system, all products and services are regulated by government. The assimilated model builds on the regulated system by allowing biomedical practitioners to integrate CAM products and services into their care. However, not only does this model perpetuate the divide between CAM and orthodox clinicians, but it also disregards the comprehensive training required to safely and effectively implement CAM.

The patient-centred model turns the focus of healthcare towards the patient and away from the practitioner. Client’s wishes become a pivotal part of any consultation and practitioners work closely together to more effectively meet patient needs. The benefit of this approach is that the divide between alternative and orthodox is narrowed and the true purpose of healthcare – the improvement of patient health and wellbeing – is accentuated.50 By minimising practitioner ownership over health, the model also facilitates a more interdisciplinary approach to client care.14

There is now evidence to suggest that patient-centred models of integrative healthcare are being applied in clinical practice. In an Israeli study,51 for instance, CAM practitioners were contracted to work within orthodox outpatient clinics or hospitals on a part-time basis; inside the hospitals, CAM practitioners worked within specific medical departments. Interviews with 10 alternative practitioners and nine biomedical clinicians across the four Jewish community hospitals found the integration of CAM practitioners into the hospital setting improved teamwork and collaborative attitudes, complemented other health services and addressed concerns relating to patient quality of life, although the extent of these benefits was not fully explored. The marginalisation of CAM practitioners was still evident, particularly with regards to employment status, office location, remuneration and participation in clinical rounds. Many CAM practitioners believed the holistic nature of their work was constrained by placement in specialised departments. The provision of complementary therapists at the hospital level rather than departmental level could address some of these concerns.

A number of integrative models have also been developed for the primary care setting. In one Israeli family practice,52 the medical practitioner administered the role of gate keeper. In this capacity, the physician was required to review and diagnose all presenting cases, and then refer the cases onto the most suitable healthcare professional for clinical management. This gatekeeping primary care model is not dissimilar to that recently developed by a group of conventional and CAM practitioners in Sweden.53 There is concern, however, that such a model could perpetuate medical dominance and control over patients and other healthcare professionals. Additionally, this model may be easily tainted by practitioner bias, therapy preference and level of knowledge. There are also philosophical and diagnostic differences between professions that need to be considered when triaging cases with a single practitioner.

Another integrative approach that may be used in the primary care setting is that recently administered by Get Well UK.54 The CAM pilot project, which was conducted in 2007–08, involved 35 general practitioners (GPs) across two health centres in Northern Ireland, 713 patients with a variety of musculoskeletal and mental health problems, and 16 CAM practitioners from seven different CAM fields. The project encouraged GPs from participating health centres to refer eligible patients to pertinent CAM practitioners via the Get Well UK customer service team, which facilitated the selection of practitioners, the booking of appointments, the coordination of care and the reporting of outcomes. Appropriate assessment and care were provided by single or multiple CAM practitioners and, upon patient discharge, was summarised and reported back to the GP. Even though the outcomes of the pilot study strongly support an integrative healthcare approach, including improvements in patient symptoms, wellbeing, medication use and work absenteeism, it is not clear how the effectiveness of this approach compares to conventional care alone or to a single-centre integrative healthcare model, and whether this system offers similar benefits to patients with other illnesses.

A more collaborative model of integration, which addresses prior concerns about power, autonomy, respect and decision making, is that reported by Chung et al.55 In this Hong Kong-based integrative health clinic (the first of its kind in Hong Kong), patients received initial screening and physical assessment by a registered nurse. The patient’s case was then reviewed by a team of nurses, conventional physicians, TCM physicians and CAM practitioners working within the clinic. Although the majority of consumers using the clinic reported a high level of satisfaction with practitioner performance and various aspects of service delivery, there was concern that the case conferencing of every patient (including new and continuing cases) may be cost-prohibitive and time inefficient for regions demonstrating high service demand. The economic and clinical implications of this model warrant further investigation.

As well as the more traditional clinical settings, integrative healthcare may also be delivered through integrative wellness and health promotion programs in the workplace. These programs, which are often embraced by medium to large companies, can incorporate services from a range of health professionals, including naturopaths, chiropractors, medical practitioners, fitness trainers, ergonomists, massage therapists and/or registered nurses. Evidence to date indicates that the implementation of these programs reduces staff absenteeism and healthcare costs at the same time as improving work performance, job satisfaction and employee quality of life.56 In addition to these positive outcomes, integrative wellness programs also demonstrate generous returns on program investment.57 What remains unclear is how the skill mix affects these employee outcomes and whether the inclusion of CAM practitioners within these programs can contribute to significant improvements in work performance.

Despite the level or model of integration selected, physician support will be fundamental to the success of the service, as will practitioner competency (i.e. credentialling) and effective administration.58 Other issues that need to be addressed in order to improve program success are equitable access, funding, practitioner hierarchy,14 triage of cases, communication between clinicians and the selection of appropriate providers and therapies.52

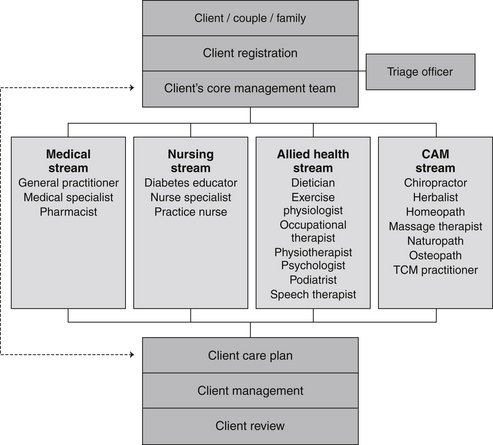

A model of integrative healthcare that takes these concerns into consideration, at the same time as addressing the limitations of the systems previously discussed, is the integrative healthcare centre model (IHCCM). This interdisciplinary, publicly funded, non-hierarchical, client-centred model follows a four-stage process. The first stage of the model is patient registration. At this point, patients are required to register their details at centre reception, after which they will be directed either to the clinical waiting area (for follow-up visits) or to the triage officer (for newly presented cases). The triage officer, who may be a nurse practitioner, physician or other adequately qualified health professional, assesses the client and in conjunction with advanced diagnostic reasoning software (i.e. a modified clinical decision support system), determines which health professional will be the most appropriate to manage the presenting complaint. This person is referred to as the patient’s ‘primary practitioner’. As well as controlling for gatekeeping and practitioner bias, the decision support software alerts the triage officer of other team members who may need to be involved in the client’s care. The primary and other practitioners who are identified by the software are collectively referred to as the ‘core management team’. Once a team is identified, the patient is directed to the recommended primary practitioner for assessment, diagnosis and planning of care. Contingent on client choice, practitioner availability and workload, and the discretion of the primary practitioner, the client may be then referred to other members of the core management team so they can contribute to the patient’s plan of care.

Stringent quality assurance systems monitor client progress during their episode of care to ensure that patient management is cost-effective and expected health outcomes are achieved in a timely and efficient manner. Overseeing these systems, as well as practitioner competency, performance, recruitment and clinic administration, is the centre operations manager. Regular team conferences are held in order to facilitate the management of complex patient cases and to foster collegiality, interprofessional understanding and respect, and professional development. These meetings, together with the utilisation of shared files, standardised documentation and shared clinical outcomes, also facilitate interprofessional communication. The use of non-hierarchical consensus voting during these review meetings also ensures that necessary changes to care are evaluated, endorsed and implemented by the team. While this equitable and accessible model of care is still in the conceptual phase of development, plans are currently in place to refine and test this model for future application in clinical practice. A visual representation of the IHCCM developed by the author is presented in Figure 7.2.

Summary

The development of an integrative healthcare system will necessitate a major change in the current system of healthcare. These changes may require CAM and orthodox practitioners to redefine the parameters of their practice31 and key stakeholders to redefine the hierarchical positions of these clinicians, as well as encourage amendments to legislation that will enable the provision of adequate funding of complementary medicines and services. Several models of integrative healthcare have been presented in this chapter, of which some are expected to address the many shortfalls of conventional healthcare. Despite the argument for an integrative system of care, there remains a paucity of evidence to demonstrate IHC is any more effective than conventional care at improving client health outcomes and quality of life. Because of the increasing shift towards integrative healthcare, research is urgently needed to justify the more rapid facilitation of this movement.

Learning activities

1. Boon H., et al. From parallel practice to integrative healthcare: a conceptual framework. BMC Health Services Research. 2004;4:15.

2. Rees L., Weil A. Integrated medicine. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:119-120.

3. Hsiao A.F., et al. Variations in provider conceptions of integrative medicine. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62(12):2973-2987.

4. Berndtson K. Integrative medicine: business risks and opportunities. Physician Executive. 1998;24(6):22-26.

5. van de Mortel T. Health for all Australians. Contemporary Nurse. 2002;12(2):169-175.

6. Russello A. Severe mental illness in primary care. Abingdon: Radcliffe Publishing; 2007.

7. Duckett S. Policy challenges for the Australian healthcare system. Australian Health Review. 1999;22(2):130-147.

8. Oliveira M.D., Bevan G. Modelling hospital costs to produce evidence for policies that promote equity and efficiency. European Journal of Operational Research. 2008;185(3):933-947.

9. Gallagher C., Bailey-Flitter N. What can the NHS learn from healthcare provision in other countries? Pharmaceutical Journal. 2007;279:210-213.

10. MacLennan A.H., Myers S.P., Taylor A.W. The continuing use of complementary and alternative medicine in South Australia: costs and beliefs in 2004. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;184(1):27-31.

11. Leach M.J. Public, nurse and medical practitioner attitude and practice of natural medicine. Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery. 2004;10(1):13-21.

12. Sewitch M.J., et al. A literature review of healthcare professional attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2008;13(3):139-154.

13. Dalen J. Is integrative medicine the medicine of the future? Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159(18):2122-2126.

14. Cohen M. CAM practitioners and ‘regular’ doctors: is integration possible? Medical Journal of Australia. 2004;180:645-646.

15. Myers S. Conclusion – challenges facing integrated medicine. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

16. Sirois F.M. Motivations for consulting complementary and alternative medicine practitioners: a comparison of consumers from 1997–8 and 2005. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2008;8:16-26.

17. Snyderman R., Weil A. Integrative medicine: bringing medicine back to its roots. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(4):395-397.

18. Peters D. From holism to integration: is there a future for complementary therapies in the NHS? Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery. 2000;6:59-60.

19. Giordano J., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in mainstream public health: a role for research in fostering integration. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2003;9(3):441-445.

20. Jones D.S., Quinn S. Why functional medicine? importance of improving management of complex, chronic disease. In: Jones D.S., Quinn S., editors. Textbook of functional medicine. Washington: Gig Harbor: Institute for Functional Medicine, 2006.

21. Mann D., Gaylord S., Norton S. Moving toward integrative care: rationales, models, and steps for conventional-care providers. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2004;9:155-172.

22. White A. Is integrated medicine respectable? Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2003;11(3):140-141.

23. Wolff J.L., Boult C. Moving beyond round pegs and square holes: restructuring Medicare to improve chronic care. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2005;143(6):439-445.

24. Adams K., et al. Ethical considerations of complementary and alternative medical therapies in conventional medical settings. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2002;137(8):660-664.

25. Giannelli M., et al. General practitioners’ knowledge and practice of complementary/alternative medicine and its relationship with life-styles: a population-based survey in Italy. BMC Family Practice. 2007;8:30-38.

26. Kwan D., Hirschkorn K., Boon H. US and Canadian pharmacists’ attitudes, knowledge, and professional practice behaviors toward dietary supplements: a systematic review. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2006;6:31-41.

27. Owen D., Lewith G., Stephens C. Can doctors respond to patients’ increasing interest in complementary and alternative medicine? British Medical Journal. 2001;322:154-157.

28. Verhoef M.J., Boon H.S., Page S.A. Talking to cancer patients about complementary therapies: is it the physician’s responsibility? Current Oncology. 2008;15(Suppl 2):S88-S93.

29. Richardson J. Integrating complementary therapies into healthcare education: a cautious approach. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2001;10:793-798.

30. St George D. Integrated medicine means doctors will be in charge. British Medical Journal. 2001;322(7300):1484.

31. Giordano J., et al. Blending the boundaries: steps toward an integration of complementary and alternative medicine into mainstream practice. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2002;8(6):897-906.

32. Bensoussan A., Myers S., Carlton A. Risks associated with the practice of traditional Chinese medicine. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9(10):1071-1078.

33. Hughes E. Integrating complementary and alternative medicine into clinical practice. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;44(4):902-906.

34. Robotin M.C., Penman A.G. Integrating complementary therapies into mainstream cancer care: which way forward? Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;185:377-379.

35. Clarke-Grill M. Questionable gate-keeping: scientific evidence for complementary and alternative medicines (CAM): response to Malcolm Parker. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 2007;4(1):21-28.

36. Parker M. Rejoinder. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 2007;4(1):29-31.

37. Stone J.. Integrating complementary and alternative medicine: fresh challenges for RECs. Bulletin of Medical Ethics, 2002;(180):13-16.

38. Barrett B. Alternative, complementary, and conventional medicine: is integration upon us? Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2003;9(3):417-427.

39. Cohen M. Challenges and future directions for integrative medicine in clinical practice: ‘Integrative’, ‘complementary’ and ‘alternative’ medicine. Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine. 2005;2(3):117-122.

40. Paterson C. Primary healthcare transformed: complementary and orthodox medicine complementing each other. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2000;8:47-49.

41. Rakel D. Perspectives on integrative practice. In: Rakel D., Faass N., editors. Complementary medicine in clinical practice: integrative practice in American healthcare. Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2005.

42. Michaeli D. Integrative medicine: who needs it and why? Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(8):1205.

43. Davies P. Making sense of integrated care in New Zealand. Australian Health Review. 1999;22(4):25-47.

44. Herman P.M., Craig B.M., Caspi O. Is complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) cost-effective? a systematic review. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2005;5:11-26.

45. Leach M.J., Pincombe J., Foster G. Using horsechestnut seed extract in the treatment of venous leg ulceration: a cost-benefit analysis. Ostomy/Wound Management. 2006;52(4):68-78.

46. Sarnat R.L., Winterstein J., Cambron J.A. Clinical utilization and cost outcomes from an integrative medicine independent physician Association: an additional 3-year update. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2007;30(4):263-269.

47. Esch B.M., et al. Patient satisfaction with primary care: an observational study comparing anthroposophic and conventional care. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2008;6:74-89.

48. Myklebust M., Pradhan E.K., Gorenflo D. An integrative medicine patient care model and evaluation of its outcomes: University of Michigan Experience. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(7):821-826.

49. Willms L. Blending in: Is integrative medicine the future of family medicine? Canadian Family Physician. 2008;54(8):1085-1087.

50. Leckridge B. The future of complementary and alternative medicine – models of integration. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2004;10(2):413-416.

51. Shuval J., Mizrachi N., Smetannikov E. Entering the well-guarded fortress: alternative practitioners in hospital settings. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55(10):1745-1755.

52. Frenkel M., Borkan J. An approach for integrating complementary-alternative medicine into primary care. Family Practice. 2003;20(3):324-332.

53. Sundberg T., et al. Towards a model for integrative medicine in Swedish primary care. BMC Health Services Research. 2007;7:107-116.

54. McDade D. Evaluation of a CAM pilot project in Northern Ireland. Belfast: Social and Market Research; 2009.

55. Chung J.W.Y., et al. Evaluation of services of the integrative health clinic in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(19):2550-2557.

56. Mitchell S.G., Goetzel R.Z., Ozminkowski R.J. The value of worksite health promotion. ACSM’s Health and Fitness Journal. 2008;12(2):23-27.

57. Young J.M. Promoting health at the workplace: challenges of prevention, productivity, and program implementation. North Carolina Medical Journal. 2006;67(6):417-424.

58. Ananth S., Newman D. Risks and rewards. Hospitals and Health Networks. 60, 2002.