Chapter 6 Application – Evidence-based practice

A major consideration when selecting interventions for CAM practice is the application of evidence-based practice (EBP). This chapter will focus on the EBP framework as a means of improving clinical practice, while the exploration of specific CAM interventions will be covered in chapter 9. This shift towards EBP will enable CAM professionals to move from a culture of delivering care based on tradition, intuition and authority to a situation in which decisions are guided and justified by the best available evidence. In spite of these advantages, many practitioners remain cautious about embracing the model. Part of this opposition is due to a misunderstanding of EBP, which this chapter aims to address.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, terms such as ‘evidence-based practice’, ‘evidence-based medicine’, ‘evidence-based nursing’ and ‘evidence-based nutrition’ have become commonplace in the international literature. The more inclusive term, ‘evidence-based practice’ (EBP), has been defined as the selection of clinical interventions for specific client problems that have been ‘(a) evaluated by well designed clinical research studies, (b) published in peer review journals, and (c) consistently found to be effective or efficacious on consensus review’.1 As will be explained throughout this chapter, EBP is not just about locating interventions that are supported by findings from randomised controlled trials; EBP is a formal problem-solving framework2 that facilitates ‘the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’.3 Apart from the implications for clinical practice, the capacity of EBP to link study findings to a profession’s body of knowledge also indicates that EBP is a useful theoretical framework for research and may therefore provide an effective solution to the research–practice divide4–6 and an important impetus to the professionalisation of CAM.

The concept of EBP is not new. In fact, its origins may be traced back to ancient Chinese medicine.7 That said, notions about quality of evidence and best practice are relatively recent. Archibald Cochrane, a Scottish medical epidemiologist, conceived the concept of best practice in the early 1970s,8,9 but it was not until after Cochrane’s death in the late 1980s that medicine began to demonstrate an interest in the EBP paradigm with the establishment of the Cochrane collaboration.8,10 Since then, professional interest in EBP has grown.2,11–13 This shift towards EBP has enabled health professionals to move from a culture of delivering care based on tradition, intuition, authority, clinical experience and pathophysiologic rationale to a situation in which decisions are guided and justified by the best available evidence.2,5,9,12,14 EBP also limits practitioner and consumer dependence on evidence provided by privileged people, authorities and industry by bestowing clinicians with a framework to critically evaluate claims. Even so, there remains some debate over the definition of evidence in the EBP model.

Defining evidence

Evidence is a fundamental concept of the EBP paradigm, although there is little agreement between practitioners, academics and professional bodies as to the meaning of evidence. Indeed, the insufficient definition of evidence and the different methodological positions of clinicians and academics may all contribute to these discrepant viewpoints. From the broadest sense, evidence is defined as ‘any empirical observation about the apparent relation between events’.2 While this definition suggests that most forms of knowledge could be considered evidence,14 it is also asserted14 that the evidence used to guide practice should be ‘subjected to historic or scientific evaluation’. Given the long history of use of many CAM interventions, such as herbal medicine, acupuncture and yoga, this would suggest that traditional CAM evidence has a place in EBP. However, not all evidence is considered the same. These differences in the quality of information are known as the ‘hierarchy of evidence’.

As shown in Table 6.1, decisions based on findings from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) may be more sound than those guided by case series results. When findings from controlled trials are unavailable or insufficient, however, decisions should be guided by the next best available evidence. This is particularly relevant to the field of CAM, as many of the interventions used in CAM practice are supported only by lower levels of evidence, such as traditional evidence, and less so by evidence from RCTs and systematic reviews.

| Level I | Systematic reviews |

| Level II | Well-designed randomised controlled trials |

| Level III-1 | Pseudorandomised controlled trials |

| Level III-2 | Comparative studies with concurrent controls, such as cohort studies, case-control studies or interrupted time series studies |

| Level III-3 | Comparative studies without concurrent controls, such as a historical control study, two or more single-arm studies or interrupted time series without a parallel control group |

| Level IV | Case series with post-test or pre-test/post-test outcomes; uncontrolled open label study |

| Level V | Expert opinion or panel consensus |

| Level VI | Traditional evidence |

Adapted from National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC 1999)15 and the Centre for Evidence-based Medicine 200116

The hierarchy of evidence can also be used to identify research findings that supersede and/or invalidate previously accepted treatments and replace them with interventions that are safer, efficacious and cost-effective.2,5 Basing clinical decisions on the level of evidence is only part of the equation though, as these decisions also need to take into account the strength of the evidence (Table 6.2), specifically, the quality, quantity, consistency, clinical impact and generalisability of the research, as well as the applicability of the findings to the relevant healthcare setting (e.g. if the frequency, intensity, technique, form or dose of the intervention, or the blend of interventions, as administered under experimental conditions, is applicable to CAM practice).17,18 Of course, determining the grade of evidence may not always be straightforward, as the defining criteria of each grade may not always apply (i.e. the evidence may be generalisable, consistent and of high quality (grade A), but the techniques used are not applicable to CAM practice (grade D)). In this situation, the practitioner will need to make a decision about where the bulk of the criteria lies. For this example, it could be ranked conservatively as grade B evidence, or more favourably as grade A evidence.

Table 6.2 Strength of evidence

| Grade | Strength of evidence | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| A | Excellent | Evidence: multiple level I or II studies with low risk of bias Consistency: all studies are consistent Clinical impact: very large Generalisability: the client matches the population studied Applicability: findings are directly applicable to the CAM practice setting |

| B | Good | Evidence: one or two level II studies with low risk of bias, or multiple level III studies with low risk of bias Consistency: most studies are consistent Clinical impact: considerable Generalisability: the client is similar to the population studied Applicability: findings are applicable to the CAM practice setting with few caveats |

| C | Satisfactory | Evidence: level I or II studies with moderate risk of bias, or level III studies with low risk of bias Consistency: there is some inconsistency Clinical impact: modest Generalisability: the client is different from the population studied, but the relationship between the two is clinically sensible Applicability: findings are probably applicable to the CAM practice setting with several caveats |

| D | Poor | Evidence: level IV studies, level V or VI evidence, or level I to III studies with high risk of bias Consistency: evidence is inconsistent Clinical impact: small Generalisability: the client is different from the population studied, and the relationship between the two is not clinically sensible Applicability: findings are not applicable to the CAM practice setting |

Adapted from NHMRC 200918

Another important determinant of evidence-based decision making is the direction of the evidence. This construct establishes whether the body of evidence favours the intervention (positive evidence), the placebo and/or comparative agent (negative evidence) or neither treatment (neutral evidence) (see Table 6.3). When the direction, hierarchy or level and strength of evidence are all taken into consideration, there is a more critical and judicious use of evidence. So, rather than accepting level I or level II evidence on face value alone, these elements stress the need to also identify whether the strength of the evidence is adequate (i.e. level A or B, or possibly C) and the direction of the evidence is positive (+) before integrating the evidence into CAM practice.

Table 6.3 Direction of evidence

| + | Positive evidence – intervention is more effective than the placebo or comparative agent |

| o | Neutral evidence – intervention is as effective or no different than the placebo or comparative agent |

| – | Negative evidence – intervention is less effective than the placebo or comparative agent |

The EBP framework

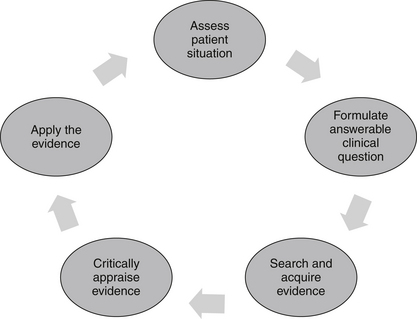

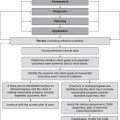

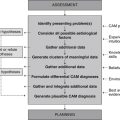

The EBP model consists of a series of steps that assist the CAM practitioner in finding an answer to a clinical problem, and then applying that solution to clinical practice (see Figure 6.1). The five-stage process begins with the identification of a clinical problem and the subsequent formation of a structured and answerable question.4,9 In order to be client-centred and relevant to the presenting case, this question needs to incorporate four key components, including the patient, interventions, condition and outcome (otherwise known as the PICO statement). Collectively, these four elements enable a practitioner to narrow down a search to a specific treatment or range of treatments that are likely to produce a precise clinical effect in a certain type of patient with a specific symptom or disease. An example of an answerable clinical question or PICO statement is: ‘What interventions, techniques, therapies (i.e. herbs, nutritional supplements, mind–body techniques, manipulative therapies, lifestyle changes) (interventions) would reduce arthralgia (outcome) in a 60-year-old woman (patient) with osteoarthritis of the hands (condition)?

Following the formulation of a suitable PICO statement, the literature is then searched for the best available evidence to answer the proposed question.4,9 This is often carried out using electronic bibliographic databases, such as Medline, the cumulative index for nursing and allied health literature (CINAHL), alternative and complementary medicine (AMED), CAM on PubMED, and the Cochrane Library. When suitable clinical evidence cannot be located, level V and level VI evidence may need to be sourced from relevant textbooks and desktop references.

Once the best available evidence has been retrieved, it is then critically appraised for its validity, quality, applicability and generalisability.4,19 A method frequently used by researchers to assess the quality of study findings is to evaluate the factors known to minimise the risk of bias, such as random assignment of treatment, concealment of treatment allocation, suitable control or comparator groups, valid and reliable instrumentation, intention-to-treat analysis and appropriate quality assurance procedures. If the study findings are deemed to be valid, reliable and applicable to the client case, and the treatment is considered appropriate according to clinical expertise, CAM philosophy and available resources,19 then the best available evidence may be integrated into clinical practice.

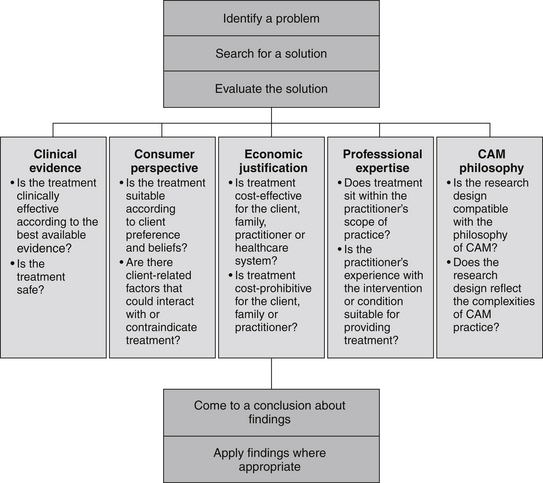

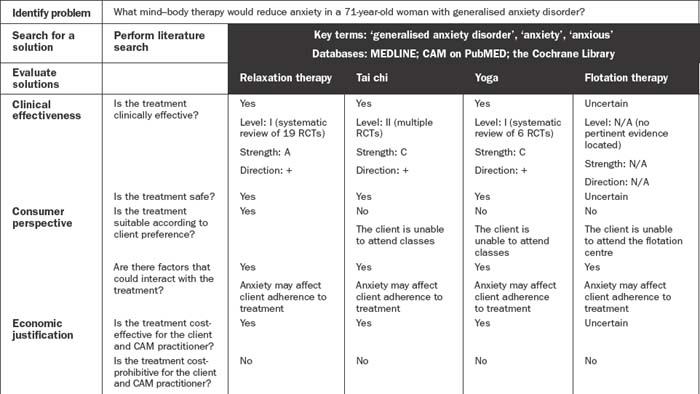

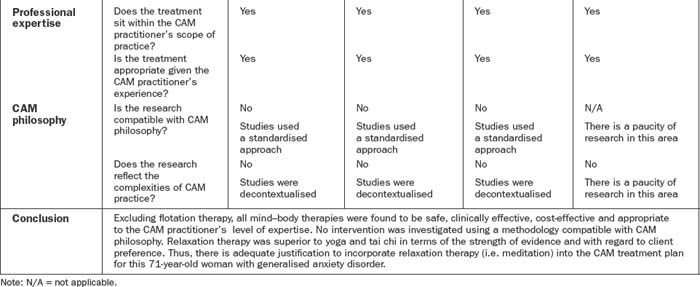

Client preferences, psychosocial needs, values, beliefs and expectations form another important component of this decision-making process.2,19 These preferences may include an aversion or inclination towards certain modalities or methods of administration, or relate to financial, cultural, personal and/or religious constraints. Put simply, effective decision making in CAM depends on the provision of professional expertise, clinical evidence, economic justification and consumer perspective, as well as due consideration of CAM philosophy. Figure 6.2 illustrates how these five components may be integrated into the evidence-based decision-making framework, and Table 6.4 demonstrates how this process can be applied to CAM practice.

Rationale for EBP

There are many benefits to CAM practitioners, consumers and the healthcare system should they adopt the EBP model. EBP gives rise, for example, to a more transparent clinical decision-making process.20 While practitioners may not welcome this increased level of scrutiny, greater accountability over decision making is likely to benefit consumers. So, as client expectations increase and practitioners become more accountable for their actions,9,21 the traditional sourcing of inconsistent and incomplete information from peers, manufacturers and historical texts may become outdated.2,22 EBP therefore challenges existing procedures and facilitates the integration of new and effective interventions into clinical practice. Yet unless practitioners are adequately informed and motivated about EBP, and unless resources are made available for staff to access evidence-based material, clinicians may have difficulty in adopting an EBP approach.4,23

According to findings from a recent nationwide survey of system-based CAM practitioners in Australia,24 these concerns are pertinent to the field of CAM. Of the 126 of 351 randomly selected naturopaths, Western herbalists, homeopaths and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners who responded to the survey, most agreed that access to the internet, free online databases and full-text journal articles would facilitate EBP uptake. Attention to major obstacles of EBP uptake, such as the lack of evidence, skills and industry support, was also important. While the small response rate limits the generalisability of these findings, the sample was considered representative of Australian CAM practitioners. What this study suggests is that even though CAM practitioners may be supportive of EBP, education and training are needed to further improve clinician understanding and application of it.

EBP also plays an important role in improving the quality of care, and reducing the costs of treatment, risk of clinical error and client mortality through improved decision making.9,12,14,25,26 Although these cost savings may be attributed to the elimination of unnecessary and ineffective interventions, as well as superfluous follow-up care, the provision of high-quality evidence may not necessarily equate to cost reductions. Instead, the cost-effectiveness of alternative interventions should be evaluated using cost–benefit analyses (CBA) and, in the absence of such data, be assessed on a case-by-case basis. If, for example, a CAM practitioner is undecided about which treatment to prescribe for a client, the client has no treatment preference, and the two treatments of choice demonstrate similar benefit (i.e. low risk of harm, ease of administration, similar degree of improvement in clinical outcomes), then it would be in the client’s best interest to consider the relative costs of the two interventions. If, say, 1 month of treatment with intervention A costs $45, and for intervention B, $29, then preference should be given to intervention B, as this treatment would bear the greatest cost–benefit to the client.

The disparate practices across clinics, institutions and health professions are another concern in healthcare,27–31 with the need for more consistent approaches to client problems being long overdue. To address the inconsistencies in clinical practice, CAM practitioners should be encouraged to adopt an EBP approach.2,27 Failure to use EBP may delay the integration of innovative treatments into clinical care,5 which could contribute to adverse client outcomes.12

Failing to deliver EBP may also reduce the credibility of the CAM profession14 and, in turn, isolate members of the profession from the multidisciplinary team. In other words, practitioners choosing to ignore EBP may lack adequate justification to continue or change clinical practices.5,14,32,33 EBP may improve multidisciplinarity6 and consistency of clinical care, but may also more effectively meet the healthcare needs of individuals.14 Despite the benefits to CAM practitioners and consumers, EBP is not without limitations.

Criticisms of EBP

There are many critics of EBP, but as yet these arguments hold little coherence or strength.20 Some of the resistance in accepting EBP has been attributed to the underlying positivist philosophy of EBP, with concerns that a reductionist approach oversimplifies or inadequately addresses complex client situations6,25 and the complexities of CAM practice. There is also an assumption that hard science is the only evidence accepted in the model.25,34,35 The belief that EBP relies only on evidence from RCTs is a common misconception. While an RCT is particularly useful for evaluating the effects of single or multiple interventions, it can be less effective in answering questions about client attitudes, preferences, experiences, prognosis and diagnosis.9,36 Thus, the criticism towards EBP may not necessarily be directed at the model per se, but towards the type of evidence accepted. A major challenge is for practitioners to recognise that other types of data, such as qualitative findings, are accepted forms of evidence in the EBP model. Of course, the type of evidence adopted should be the best available evidence and, furthermore, should be dictated by the type of question being asked.10 A question about clinical effectiveness, for example, would be best answered using data from pragmatic RCTs, a query relating to typical responders of CAM treatment would be best addressed using findings from case studies, and a question about client expectations or preferences could be appropriately answered using results from surveys or qualitative investigations.

There is related concern that the evidence derived from RCTs and systematic reviews (which are highly favoured in EBP) may not be applicable to CAM practice. One argument is that the reductionist design of these studies is incompatible with the philosophies of CAM practice,37 including the principles of holism, client centredness and individualised care. Even though holism is still frequently ignored in these study designs, some attention has been given to individualised care, with a number of RCTs and systematic reviews now beginning to compare the effectiveness of individualised CAM treatments to standardised care and/or placebo treatment.38–40

Another point of concern relates to the decontextualised nature of these study designs, particularly the lack of attention afforded to the contextual or indirect effects of treatment (i.e. the effects of the clinical environment, client preference and expectation, and the client–clinician interface). Whole systems research, which considers all aspects of the treatment approach (including those previously stated),41 attempts to address many of these shortfalls of reductionist scientific studies by gaining important insight into the complexities of real-life CAM practice. While this emerging research design serves to make clinical research more relevant to CAM practice, it does not dismiss altogether the value of RCTs and systematic reviews in EBP.

Some authorities have raised concerns that EBP may produce dehumanised, routine care14,42 by ignoring clinical expertise and client preference.25,43 Yet as well as respecting client choice,21 EBP also requires research findings to be considered alongside clinical expertise.26,33 As a result EBP is client-centred,22 individualised5 and accommodating of practitioner and client needs. In fact, if a clinician failed to acknowledge a client’s preference for a particular treatment when integrating evidence into clinical practice, the practitioner would fall short in their professional obligation to respect client wishes, which would almost certainly compromise client–practitioner rapport, treatment compliance and clinical outcomes.

The paucity of high-quality, coherent and consistent scientific evidence in complementary and alternative medicine may explain why some clinicians have difficulty engaging in EBP.5,9,36 Although systematic reviews have attempted to resolve this problem (albeit in a reductionist and decontextualised manner), clinical experience and traditional evidence are still relied upon in areas where data are absent or ambiguous.11,36 EBP uses the best available evidence to guide decisions and does not just rely on data from clinical trials.9,36 In fact, if CAM practitioners used only therapies or techniques that were based on rigorous level I and level II evidence, CAM practice would be considerably limited.

Other barriers to adopting EBP are a lack of motivation, disagreement with findings, lack of autonomy, and inadequate research and critical appraisal skills.5,12,23,24,36 The lack of time, resources and authority to make changes are also major obstacles to the introduction of EBP.5,9,23,24,36 Then again, the delivery of EBP may eliminate the time, costs and resources allocated to harmful or ineffective treatments10,21,26 and, in effect, improve the future demand on clinician time.

Another potential barrier to the integration of EBP, and one that warrants urgent attention, is the lack of evidence for EBP, specifically, the paucity of data linking EBP uptake to improvements in clinical outcomes.32,44 Until such data emerge, and given the theoretical rationale for EBP, there is no reason why CAM practitioners should not base clinical practice decisions on the best available evidence.

Summary

Even though some health professionals are cautious about embracing EBP, these practitioners need to be assured that EBP simply provides a useful and ‘scientific framework within which to identify and answer priority questions about the effectiveness of … healthcare’.45 As well as guiding clinical practice, the EBP paradigm also helps to close the research–practice divide. Integrating findings into clinical practice may eventuate only if practitioners undergo further education and if high-quality evidence on the clinical efficacy, cost–benefit and feasibility of CAM interventions (including evidence from pragmatic RCTs and whole systems research) and EBP are made available to clinicians. A greater uptake of clinical evidence within CAM practice may also help to advance the CAM profession by facilitating consistent and quality care, multidisciplinarity and the integration of CAM services into the mainstream healthcare sector. This concept of integrative healthcare is explored in greater depth in the following chapter.

Learning activities

1. Rosenthal R.N. Overview of evidence-based practices. In: Roberts A.R., Yeager K., editors. Foundations of evidence-based social work practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

2. Montori V., Guyatt G. Progress in evidence-based medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(15):1814-1816.

3. Sackett D., et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal. 1996;312(7023):71-72.

4. Dawes M., et al. Sicily statement on evidence-based practice. BMC Medical Education. 2005;5:1-7.

5. Pape T. Evidence-based nursing practice: to infinity and beyond. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 2003;34(4):154-161.

6. Trinder L. A critical appraisal of evidence-based practice. In: Trinder L., Reynolds S., editors. Evidence-based practice: a critical appraisal. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2000.

7. Sackett D.L., et al. Evidence based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

8. Hill G. Archie Cochrane and his legacy. An internal challenge to physicians’ autonomy? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2000;53(12):1189-1192.

9. McKenna H., Ashton S., Keeney S. Barriers to evidence based practice in primary care: a review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2004;41:369-378.

10. Reynolds S. The anatomy of evidence-based practice: principles and methods. In: Trinder L., Reynolds S., editors. Evidence-based practice: a critical appraisal. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2000.

11. Leung G. Evidence-based practice revisited. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2001;13(2):116-121.

12. Tod A., Palfreyman S., Burke L. Evidence-based practice is a time of opportunity for nursing. British Journal of Nursing. 2004;13(4):211-216.

13. Wyatt G. From research to clinical practice. Evidence-based practice and research methodologies: challenges and implications for the nursing profession. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2003;7(3):337-338.

14. Romyn D., et al. The notion of evidence in evidence-based practice by the nursing philosophy working group. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2003;19(4):184-188.

15. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC; 1999.

16. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Oxford centre for evidence-based medicine levels of evidence. Oxford: Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; 2001.

17. Newman M.G., Weyant R., Hujoel P. JEBDP improves grading system and adopts strength of recommendation taxonomy grading (SORT) for guidelines and systematic reviews. Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice. 2007;7(4):147-150.

18. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). NHMRC additional levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines – Stage 2 consultation. Canberra: NHMRC; 2009.

19. Scales C.D., et al. Evidence based clinical practice: a primer for urologists. Journal of Urology. 2007;178(3):775-782.

20. Leach M.J. Evidence-based practice: A framework for clinical practice and research design. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2006;12(5):248-251.

21. Klardie K., et al. Integrating the principles of evidence-based practice into clinical practice. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2004;16(3):98-105.

22. Baxter R., Baxter H. Clinical governance. Journal of Wound Care. 2002;11(1):7-9.

23. Grol R., Wensing M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Medical Journal of Australia. 2004;180:S57-S60.

24. Leach M.J., Gillham D. Attitude and use of evidence-based practice among complementary medicine practitioners: a descriptive survey. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2009;15(3):S149-S150.

25. Williams D., Garner J. The case against ‘the evidence’: a different perspective on evidence-based medicine. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:8-12.

26. Dickersin K., Straus S.E., Bero L.A. Evidence based medicine: increasing, not dictating, choice. British Medical Journal. 2007;334(Suppl.1):S10.

27. Ahmed T.F., et al. Chronic laryngitis associated with gastroesophageal reflux: prospective assessment of differences in practice patterns between gastroenterologists and ENT physicians. American Journal of gastroenterology. 2006;101(3):470-478.

28. Janson S., Weiss K. A national survey of asthma knowledge and practices among specialists and primary care physicians. Journal of Asthma. 2004;41(3):343-348.

29. Jefford M., et al. Different professionals’ knowledge and perceptions of the management of people with pancreatic cancer. Asia–Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;3(1):44-51.

30. Novak K.L., Chapman G.E. Oncologists’ and naturopaths’ nutrition beliefs and practices. Cancer Practice. 2002;9(3):141-146.

31. Yeh K.W., et al. Survey of asthma care in Taiwan: a comparison of asthma specialists and general practitioners. Annals of Allergy. Asthma and Immunology. 2006;96(4):593-599.

32. Goodman K.W. Ethics and evidence-based medicine: fallibility and responsibility in clinical science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

33. Zeitz K., McCutcheon H. Evidence-based practice: to be or not to be, this is the question!. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2003;9(5):272-279.

34. Bhandari M., Giannoudis P.V. Evidence-based medicine: What it is and what it is not. Injury. 2006;37(4):302-306.

35. Walker K. Why evidence-based practice now? A polemic. Nursing Inquiry. 2003;10(3):145-155.

36. Straus S., McAlister F. Evidence-based medicine: a commentary on common criticisms. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2000;163(7):837-841.

37. Fonnebo V., et al. Researching complementary and alternative treatments – the gatekeepers are not at home. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2007;7:7.

38. Cherkin D.C., et al. A randomized trial comparing acupuncture, simulated acupuncture, and usual care for chronic low back pain. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(9):858-866.

39. Guo R., Canter P.H., Ernst E. A systematic review of randomised clinical trials of individualised herbal medicine in any indication. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2007;83:633-637.

40. White A., et al. Individualised homeopathy as an adjunct in the treatment of childhood asthma: a randomised placebo controlled trial. Thorax. 2003;58(4):317-321.

41. Verhoef M.J., et al. Whole systems research: moving forward. Focus on Alternative Complementary Therapies. 2004;9(2):87-90.

42. Fleming K. The knowledge base for evidence-based nursing: a role for mixed methods research? Advances in Nursing Science. 2007;30(1):41-51.

43. Closs S., Cheater F. Evidence for nursing practice: a clarification of the issues. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;30(1):10-17.

44. Fulbrook P., Harrison L. Linking evidence-based practice to clinical outcomes. Connect: The World of Critical Care Nursing. 2006;5(1):1.

45. Sackett D., Rosenberg W. The need for evidence-based medicine. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1995;88(11):620-624.