Appendix and abdominal abscess

OPEN APPENDICECTOMY

Appraise

1. Acute appendicitis is essentially a clinical diagnosis. A detailed history and careful examination of the patient carry more weight in making the diagnosis than embarking on radiological investigations, although these investigations can be useful to rule out alternative diagnoses.

2. Although appendicectomy is still the most common reason for laparotomy, remember the following:

Young children and the elderly may have atypical presentations of appendicitis and also have a higher mortality and morbidity from this condition.1

Young children and the elderly may have atypical presentations of appendicitis and also have a higher mortality and morbidity from this condition.1

Female patients may have a gynaecological cause for pain and tenderness in the right iliac fossa rather than appendicitis. Order a pelvic ultrasound scan and consider carrying out a diagnostic laparoscopy in such cases.

Female patients may have a gynaecological cause for pain and tenderness in the right iliac fossa rather than appendicitis. Order a pelvic ultrasound scan and consider carrying out a diagnostic laparoscopy in such cases.

There is good evidence that in female patients, appendicitis, even when perforated, does not adversely affect fertility, so you need not perform a mandatory appendicectomy in equivocal cases.2

There is good evidence that in female patients, appendicitis, even when perforated, does not adversely affect fertility, so you need not perform a mandatory appendicectomy in equivocal cases.2

Although elderly patients do develop appendicitis, consider other pathology such as perforating carcinoma of the caecum and diverticulitis, which may mimic its presenting features. In case of doubt, use a midline incision so you can carry out a full examination of the peritoneal cavity.

Although elderly patients do develop appendicitis, consider other pathology such as perforating carcinoma of the caecum and diverticulitis, which may mimic its presenting features. In case of doubt, use a midline incision so you can carry out a full examination of the peritoneal cavity.

Computed tomography (CT) is the most sensitive imaging technique for diagnosing appendicitis.3 In view of the radiation dose, reserve this investigation for those in whom a negative laparotomy represents an unjustifiable risk.

Computed tomography (CT) is the most sensitive imaging technique for diagnosing appendicitis.3 In view of the radiation dose, reserve this investigation for those in whom a negative laparotomy represents an unjustifiable risk.

3. Tend to treat conservatively a patient with symptoms for 5 or more days in whom you find a mass in the right iliac fossa. Give a 7-day course of intravenous antibiotics such as co-amoxiclav and metronidazole, withhold oral feeding and replace fluid intravenously. Mark the extent of the mass on the abdominal wall. Perform an ultrasound or CT scan to exclude the presence of a large abscess that can be drained percutaneously. Carefully monitor the patient and perform an operation only if:

4. Some surgeons carry out diagnostic laparoscopy whenever they suspect appendicitis, proceeding to laparoscopic appendicectomy if the diagnosis is confirmed.

5. Avoid removing a normal appendix incidentally during other operations, such as cholecystectomy. It is a possible cause of complications such as wound infection and subsequent adhesive intestinal obstruction.

PREPARE

1. Wound infection is the most common complication following operation for acute appendicitis, so routinely give 500 mg of metronidazole and a broad-spectrum antibiotic (e.g. co-amoxiclav) intravenously at induction of anaesthesia.

2. In patients with clinically severe acute appendicitis who are demonstrating signs of systemic sepsis, commence intravenous metronidazole and a broad-spectrum antibiotic as soon as the decision to operate is made.

3. Patients who have a perforated appendix require a full 5-day course of broad-spectrum antibiotic and metronidazole.

Access

1. As a routine employ a Lanz incision in a skin crease. This modification of the gridiron incision transversely crosses McBurney’s point – the junction of the middle and outer thirds of a line joining the anterior superior iliac spine and the umbilicus. The incision starts 2 cm below and medial to the right anterior, superior iliac spine and extends medially for 5–7 cm. It may be possible to site it lower in a young girl so that the scar lies below the waistline of a bikini.

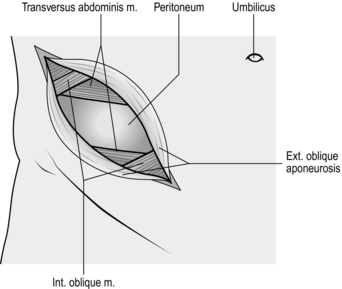

2. Alternatively, use the traditional gridiron incision, 5–8 cm long, in line with the external oblique fibres if you anticipate the need to extend the exposure (Fig. 7.1). The incision crosses McBurney’s point at right-angles to the spino-umbilical line, one-third above, two-thirds below. If necessary, the external oblique muscle and aponeurosis can be split in both directions and the internal oblique and transversus muscles can be cut to convert the incision into a right-sided Rutherford Morrison incision.

3. If appendicitis is one of a number of likely diagnoses, opt for a lower midline incision.

Opening the abdomen

1. Incise the skin cleanly with the belly of the knife. Divide the subcutaneous fat, Scarpa’s fascia and subjacent areolar tissue to expose the glistening fibres of the external oblique aponeurosis. In the gridiron approach these fibres run parallel to the skin incision.

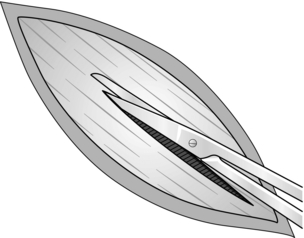

2. Stop the bleeding. Incise the external oblique aponeurosis in the line of its fibres. Start with a scalpel, then use the partly closed blades of Mayo’s scissors (Fig. 7.2) while your assistant retracts the skin edges.

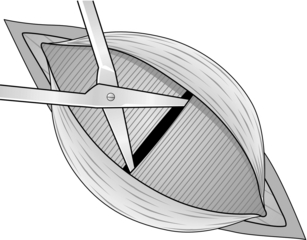

3. Retract the external oblique aponeurosis to display the fibres of the internal oblique muscle, which run at right-angles. Split internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, using Mayo’s straight scissors (Fig. 7.3). Open the blades in the line of the fibres and use both index fingers to widen the split. Provided the scissors are not thrust in violently, the transversalis fascia and peritoneum are pushed away unopened.

4. Stop the bleeding. Have the muscles retracted firmly to display the fused transversalis fascia and peritoneum.

5. Pick up a fold of peritoneum with toothed dissecting forceps and grasp the tented portion with artery forceps. Release the dissecting forceps and take a fresh grasp to ensure that only the peritoneum is held. Make a small incision through the peritoneum with a knife. Allow air to enter the peritoneal cavity, so that the viscera fall away. Use scissors to enlarge the hole in the line of the skin incision. Now protect the wound edges with swabs or skin towels.

Assess

1. Look. Is there any free fluid or pus? If so, take a specimen for microscopy and culture.

2. Find the caecum, identify a taenia and follow it distally to the base of the appendix. Insert a finger and lift out the appendix by pushing from within, not by pulling from without.

3. If the appendix is not evident, push your index finger posteriorly until it comes to lie on the peritoneum over the psoas muscle. Then, maintaining contact with the posterior peritoneum, draw your finger to the right until it can go no further. The caecum should now lie between the ‘hook’ of your finger and the right limit of the iliac fossa, and may be gently pushed out onto the surface. In some cases you may need to mobilize the caecum by incising the parietal peritoneum in the paracolic gutter, in order to raise the caecum on its mesentery, especially if the appendix is adherent retro-caecally. If the caecum is not evident, remember that it sometimes lies quite high, under the right lobe of the liver.

4. Confirm the diagnosis: the appendix, or more usually its tip, is swollen, congested, inflamed, even gangrenous, often with fibrin deposition, turbid fluid or frank pus.

Action

1. Mobilize the appendix from base to tip by gently moving or peeling away adherent structures. Remember that the artery enters from the medial aspect. If the tip is adherent, improve the view. Do not dissect blindly. If necessary, extend the incision. Apply Babcock’s tissue forceps to enclose, but not grasp, an uninflamed portion of the appendix, to hold it so you can view the mesentery against the light and identify the artery.

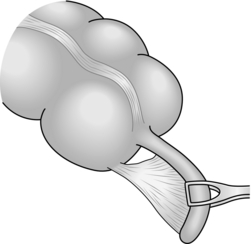

2. Pass one blade of the artery forceps through the mesoappendix and clamp the vessels (Fig. 7.4). If it is thickened, take the mesoappendix in two bites. Divide the mesoappendix distal to the clamp and ligate the vessel gently but firmly with 2/0 Vicryl or similar material, ignoring the slight back bleeding from the distal cut end.

3. Crush the base of the appendix with a haemostat then replace the clamp 0.5 cm distal to the crushed segment. Ligate the crushed segment with 2/0 Vicryl. Apply a haemostat to the ligature ends after trimming them.

4. Cut off the appendix just distal to the haemostat.

5. There is no need to invaginate the appendix stump by use of a purse-string suture, nor should the appendix stump be diathermized.

Closure

1. Pick up the edges of the peritoneum around the entire incision with fine haemostats to allow easy and safe suturing of the opening with continuous 2/0 Vicryl or similar material.

2. Insert interrupted stitches of the same material into the internal oblique muscle with just enough tension to appose but not strangulate the muscle fibres. Now close the external oblique aponeurosis with a continuous Vicryl stitch.

3. Apply povidone-iodine solution to the wound once the peritoneum is closed.

4. Appose the subcuticular tissues with fine sutures in an obese patient and close the skin with a continuous absorbable subcuticular suture or clips.

Postoperative

1. In the absence of general peritonitis, start oral fluids and a light diet as tolerated when the patient is fully awake.

2. If the appendix was perforated, and particularly in a high-risk patient, continue antibiotics for 5 days. These should be given intravenously until gut function returns.

3. Remove any drain after 2–3 days unless there is still profuse discharge.

4. Monitor the wound if pyrexia develops, and exclude chest and urinary infection.

Complications

1. Wound infection develops occasionally in patients with mild appendicitis but has a higher incidence in those who have had a gangrenous or perforated appendix removed. Anaerobic Bacteroides and aerobic coliform organisms are usually responsible. Examine the wound regularly and remove some of the skin suture or clips if there is evidence of infection, to allow any pus to drain. Check the results of any microbiological investigations taken at the time of surgery and tailor antibiotic therapy accordingly.

2. If pyrexia develops, always carry out a rectal examination. Pelvic infection produces localized heat, ‘bogginess’ and tenderness. Repeat the examination at intervals to detect if an abscess develops and ‘points’: be willing to aspirate it using a needle inserted through the vagina or rectum. If needle aspiration confirms the presence of an abscess, gently thrust closed, long-handled forceps into the cavity to drain it into the rectum. Ultrasound or radiological imaging may help if you are uncertain and may allow percutaneous drainage of a collection.

3. Reactive haemorrhage is infrequent, but occasionally the ligature falls off the appendicular artery. Return the patient to the operating theatre and re-open the wound to catch and re-ligate the artery.

4. Faecal fistula develops in two circumstances. Either the patient has unsuspected Crohn’s disease or in florid appendicitis the appendicular stump or adjacent caecum has undergone necrosis. In the presence of necrosis do not over-optimistically rely on suturing the defect. Prefer to insert a large tube in the hole and suture the margins of the hole to the anterior abdominal wall where the tube emerges. The tube can be removed after 2 weeks and the fistula will heal spontaneously.

References

1. Blomqvist PG, Andersson RE, Granath F, et al. Mortality after appendectomy in Sweden, 1987–1996. Ann Surg 2001;233:455–60.

2. Andersson R, Lambe M, Bergstrom R. Fertility patterns after appendicectomy: historical cohort study. Br Med J 1999;318:963–7.

3. Paulson EK, Kalady MF, Pappas TN. Suspected appendicitis. N Engl J Med 2003;348:236–42.

LAPAROSCOPIC APPENDICECTOMY

Appraise

1. Most hospitals now have advanced laparoscopic equipment available and as a result the majority of appendicectomies are performed laparoscopically,1 which has been shown to be as efficacious as open appendicectomy even for the treatment of complicated appendicitis.2 Advantages claimed are decreased wound infection, reduced postoperative pain, better cosmesis and accelerated recovery, especially in obese individuals.3 Laparoscopy also allows detailed pelvic and abdominal examination, which is particularly valuable in young women where preoperative diagnostic accuracy is low.

2. However, increased technical difficulty, longer operating time and increased risk of intra-abdominal abscess may offset these potential advantages.1,4,5

3. There are no absolute contraindications, and relative contraindications are the same as for other laparoscopic procedures.

Prepare

1. Obtain informed consent for both laparoscopic and open appendicectomy. Administer parenteral metronidazole and broad-spectrum antibiotics during anaesthetic induction.

2. Laparoscopic appendicectomy requires general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation and muscle relaxation.

3. Place the patient supine. In females, the lithotomy position allows preoperative vaginal examination. You and your assistant stand on the patient’s left side with the monitor on the right. The nurse also stands on the right, towards the foot end of the table.

4. Catheterize the urinary bladder to reduce risk of injury.

Access

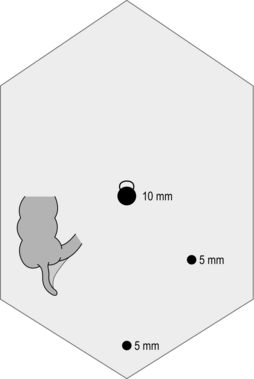

1. There is a great degree of variation between surgeons when deciding upon optimal port site configuration. Whichever configuration is used, it is essential to have a clear view of the right iliac fossa and for port site placement to allow adequate triangulation of the instruments on the appendix. Induce pneumoperitoneum, preferably using a Hasson’s open technique at the umbilicus. Introduce a 10-mm port at the umbilicus. Set the insufflator pressure to 12 mmHg.

2. Use a 5-mm telescope if available. It can be used in all available ports and, therefore, allows a greater degree of flexibility when trying to obtain the best possible view. This flexibility is increased further if a 30º telescope is used. Insert the telescope through the umbilical port. Inspect the peritoneal cavity and confirm the diagnosis. To aid visualization of the structures in the right iliac fossa and pelvis, rotate the patient to the left side with some head-down tilt.

3. Introduce two 5-mm ports, one in the lower midline above the pubic symphysis, avoiding the bladder, and one in the left iliac fossa, lateral to the inferior epigastric artery. Always place ports under direct vision, to avoid inadvertently damaging bowel or vascular structures (Fig. 7.5).

Assess

1. Place the 5-mm telescope in the left iliac fossa port. With the help of atraumatic graspers in the other ports, examine all other pelvic and abdominal organs to exclude an ovarian cyst, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, cholecystitis, perforated peptic ulcer, Meckel’s diverticulum, colonic diverticulitis and Crohn’s disease. Your ability to examine abdominal contents is much greater using laparoscopy than at open surgery through a small incision.

2. Identify the appendix which, in early appendicitis, may appear normal if mucosal inflammation has not yet extended to the peritoneum.

3. Plan to remove an apparently ‘normal’ appendix if you can find no other cause for the patient’s pain.

Action

1. Your intention is to separate the appendix from its mesentery using diathermy dissection. The appendix mesentery is not removed. If this is a late presentation with advanced inflammation and oedema, this approach may not be possible. You may need to divide the appendix base and mesentery en masse, using a vascular stapler such as the EndoGIA Universal (Covidien).

2. Identify the appendix and aim to mobilize it fully before attempting to remove it. Break down inflammatory adhesions using blunt suction dissection. Occasionally, some lateral mobilization of the caecum may be necessary using scissor or hook diathermy dissection.

3. With the appendix tip elevated, identify the appendix base. The mesoappendix immediately adjacent to the appendix base is thin and usually only consists of a layer of peritoneum. Break down the peritoneum by carefully inserting a Petelin’s forceps and opening the jaws, creating a small window in the mesoappendix. This window is a useful place to start separating the mesentery with a diathermy hook. Vessels close to the appendix are small and can be divided using diathermy alone, with minimal bleeding. If you cannot control an arterial spurter in this manner you may need to apply a clip through the 10-mm umbilical port. If dissection is difficult, insert a third port in the right flank. An assistant can hold the mesentery while you hold the appendix, so facilitating the separation. Continue dissecting until the appendix is completely free from the mesoappendix.

4. Introduce a Vicryl Endoloop (Ethicon) through the umbilical port and place it around the base of the appendix. Place two ties close to the caecum and the third tie approximately 1 cm distal to the first two. Transect the appendix, leaving two ties on the caecum. If the appendix base is friable and oedematous, divide it using a stapler, including some caecal wall if necessary.

5. Do not invaginate or diathermize the appendix stump. Remove any faecal residue from the appendix stump with a suction catheter, but avoid extensive saline irrigation unless there is gross contamination of the abdominal cavity. If there is contamination with pus and blood, perform extensive saline lavage of the right lower abdomen, pelvis and right subphrenic space until the irrigation fluid runs clear. In case of difficulty, leave a small-bore tube drain in the pelvis.

6. The appendix base can usually be grasped and retrieved via the 10-mm umbilical port. If the appendix is very friable, use a retrieval bag to help prevent contamination.

Checklist

1. Inspect the pelvic, subphrenic and subhepatic spaces for any collection and use extensive saline irrigation if there is contamination.

2. Check the appendix stump to ensure that it is intact and safely closed.

3. Check for haemostasis and that any applied clips are well secured.

4. Ensure that there is no injury to the surrounding viscera.

Closure

1. Withdraw the ports under vision and try to allow all of the insufflation gas to escape.

2. Close the rectus sheath of the 10-mm incision site with a long-acting absorbable suture such as PDS. Close the skin with subcuticular absorbable sutures.

3. Infiltrate long-acting local anaesthetic at the port sites.

Postoperative

1. In the absence of general peritonitis allow oral fluids and food once the patient is fully awake.

2. Encourage the patient to get out of bed and walk on the day of operation. Most patients can be discharged on the first postoperative day and almost all by the second.

3. Continue metronidazole and a broad-spectrum antibiotic such as co-amoxiclav for 5 days if there was extensive sepsis or contamination, especially in high-risk patients. The antibiotics should be given parenterally until the patient is discharged.

4. If pyrexia develops, check the wounds and exclude chest and urinary infection.

Complications

1. Bleeding is one of the most common complications. Possible sources include the inferior epigastric artery, appendicular artery, retroperitoneal vessels or the staple line. You can injure the inferior epigastric artery when introducing the left iliac fossa port. Avoid this by placing the port well lateral to the rectus abdominus muscle. Attempt to identify and control the source of bleeding by re-laparoscopy if possible, before converting to open surgery.

2. Perforation of the bowel can occur either from puncture by the trocar, inadvertent electrosurgical injury or slippage of the appendix stump ligature. If you are an experienced laparoscopic surgeon you may close the perforation laparoscopically. Caecal perforation may be difficult to close laparoscopically, especially when it is inflamed and thick-walled. In these circumstances, convert to an open procedure.

3. Avoid injury to the bladder by catheterization and by introducing the suprapubic port under direct vision.

4. Postoperative intra–abdominal and pelvic abscess occurs in 3–5% of patients and can be detected or confirmed by ultrasound or computed tomography (CT). Perform percutaneous drainage under imaging guidance.

5. Significant wound infection is unusual. Examine the wound regularly and remove the superficial sutures or clips if there is evidence of infection.

6. There are several reports of incomplete appendicectomy leading to recurrent appendicitis. Avoid this problem by carefully identifying the appendix base during dissection.

7. Incisional hernia may develop through the trocar site, rarely complicated by a faecal fistula.

8. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus can occur after appendicectomy, especially in the elderly. Reduce the risk by using low-molecular-weight heparin prophylaxis, anti-thromboembolic stockings and intermittent pneumatic calf compression devices intra-operatively.

References

1. Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, et al. Comparison of outcomes after laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for acute appendicitis at 222 ACS NSQIP hospitals. Surgery 2010;148(4):625–35.

2. Yau KK, Siu WT, Tang CN, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. J Am Coll Surg 2007;205(1):60–5.

3. Enochsson L, Hellberg A, Rudberg C, et al. Laparoscopic vs open appendectomy in overweight patients. Surg Endosc 2001;15(4):387–92.

4. Sauerland S, Lefering R, Holthausen U, et al. Laparoscopic vs conventional appendectomy: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg 1998;383(3–4):289.

5. Ortega AE, Hunter JG, Peters JH, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of laparoscopic appendectomy with open appendectomy. Am J Surg 1995;169:208–12.

FURTHER READING

O’Reilly MJ, Reddick EJ, Miller WD, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy. In: Zucker KA, editor. Surgical Laparoscopy. Update. St Louis; 1993. p. 301–26.

Richardson WS, Hunter JG. Complications in appendectomy. In: Ponsky JL, editor. Complications of Endoscopic and Laparoscopic Surgery. Prevention and Management. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. p. 171–6.

APPENDIX MASS

Appraise

1. This is usually a late presentation of acute appendicitis.

2. It may result from the adherence of omentum and other viscera to the inflamed appendix. More usually the appendix has ruptured and an abscess has formed, its walls comprising the fibrin-lined omentum and adherent viscera.

3. Antibiotics are commonly given even when there are no clinical features of sepsis and the white cell count is not raised.

4. Provided the patient is well, with no features of sepsis, toxicity or peritonitis, expectant treatment without operation is the preferred management. Mark out the margins of the mass and regularly monitor progress. Provided the marked margins of the mass do not extend and features of toxaemia or peritonitis do not develop, wait for the mass to resolve.

5. Ultrasound scanning or computed tomography (CT) is valuable to confirm the diagnosis and determine whether an abscess is present, which can then be drained percutaneously.1 If it extends into the pelvis it may be amenable to drainage transrectally under ultrasound guidance.

6. Perform open drainage only if worsening toxaemia or peritonitis develop, or if percutaneous drainage is not feasible or fails.

7. The subsequent management of patients with a resolved abscess remains controversial. Conventionally, the patient is re-admitted for interval appendicectomy after 1–2 months. However, at such operations one frequently finds no evidence of the appendix and, if no interval appendicectomy is undertaken, it is only rarely that recurrent appendicitis develops.2

Action

1. If you find on entering the abdomen that you are within the abscess cavity, do not rush to explore the wound. Take a specimen of the contents of the cavity for bacterial culture and to determine the antibiotic sensitivity of the contained organisms. Gently and thoroughly aspirate all pus and debris. Explore the cavity with your finger to decide whether it is safe to enlarge the opening without damaging viscera or disrupting the cavity wall.

2. If you gain an improved view you may see the appendix and be able to remove it safely. Sometimes the terminal part has separated and you will need to remove it piecemeal.

3. Sweep your finger round the cavity to identify any loose contents and remove them. Thoroughly aspirate any pus.

4. If you cannot find the appendix or if it is unsafe to open up the abscess cavity, insert a drain, closing the wound layers loosely around it.

5. If, when you open the abdomen, you enter the peritoneal cavity and find a mass lying on the posterior wall, pack it off from the remainder of the abdomen and gently explore it to determine if there is a plane of cleavage into the interior. Remember, inflamed tissues are friable; respond to the findings and be willing to stop if you encounter difficulty.

6. The mass or abscess may lie retrocaecally, retroileally, or within the pelvis. Be prepared to pack off the rest of the abdomen and mobilize the caecum by incising the peritoneum in the paracolic gutter so you can gently lift it off the mass. Now explore the mass to decide whether to enter it or leave it.

7. Whether you open the mass or leave it, insert a drain into the peritoneal cavity to provide a track for any pus.

SUBPHRENIC AND SUBHEPATIC ABSCESS

Appraise

1. An abscess may form following major surgical procedures, operations performed in the presence of infection, or sometimes spontaneously following perforation of a viscus. It may result from a retained foreign body, necrotic tissue, inadequate drainage of blood or contaminated fluid, or an anastomotic leak. The abscess may develop above the liver (subphrenic), below the liver (subhepatic), along either paracolic gutter, between loops of bowel in the mid-abdomen or in the true pelvis.

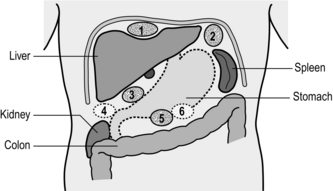

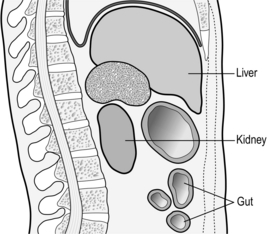

2. Reserve the term ‘subphrenic’ for an abscess lying immediately below the diaphragm. On the right it lies above the right lobe of the liver, on the left it lies above the left lobe of the liver, gastric fundus and spleen (Fig. 7.6). Right subhepatic collections may be anterior (paraduodenal) or posterior (suprarenal, Fig. 7.7). Left subhepatic collections may lie anterior to the stomach and transverse colon or posteriorly in the lesser sac.

3. Suspect the diagnosis if the patient develops rigors, swinging pyrexia, toxicity and leucocytosis. In the presence of a subphrenic abscess the hemidiaphragm may be elevated, as demonstrated on a chest X-ray, and a reactive pleural effusion often develops above the diaphragm. You may see a fluid level with gas above if leakage from a viscus or anastomosis has developed, or in the presence of gas-forming organisms. Aspirate a specimen of pus for culture and determination of antibiotic sensitivity. CT or ultrasound scans are valuable means of confirming an abscess, and a radiolabelled white blood cell scan may reveal an occult abscess that is not detectable by other imaging methods.

4. The first-line method of dealing with subphrenic or subhepatic abscess should be percutaneous drainage. This is usually effective even for recurrent abscesses.1 A needle is inserted under ultrasound or CT guidance to avoid damaging adjacent structures. A flexible guidewire is then passed through the needle, which is withdrawn. A bevel-tipped catheter is passed over the guidewire into the cavity and the guidewire is then withdrawn. This is the Seldinger technique. This technique may not be successful in obtaining drainage of multiloculated abscesses but these may be successfully drained laparoscopically.2 Send aspirated material for culture and to be tested for antibiotic sensitivity.

5. Open operation is now rarely necessary for large, loculated or recurrent abscesses and those containing necrotic or inspissated material.

6. The choice of approach depends on the site of the abscess. Ideally, an extrapleural, extra-peritoneal approach avoids the possibility of contaminating the peritoneal or pleural cavities. As a rule this is possible only for posterior collections, although a right anterior subphrenic abscess can sometimes be approached extra-peritoneally. Multiple or loculated abscess cavities usually demand a transperitoneal approach.

Action

Posterior approach

1. Place the patient in the full lateral position with the affected side uppermost. Identify the 12th rib and make a 10-cm transverse incision crossing its middle.

2. Cut down on to the rib, incise and elevate the periosteum so you can excise the rib. Incise the bed of the rib cephalad to the middle, to avoid entering the pleural cavity. Divide the origin of the diaphragm and displace the kidney forwards.

3. Feel for the lower edge of the liver and explore below it, using a needle and aspirating syringe to seek out pus. To drain a subphrenic abscess, separate the peritoneum from the undersurface of the diaphragm. When you find it, open the cavity, suck out the pus and debris. Explore it with your finger to avoid leaving necrotic or inspissated material. Now insert a drain.

Anterolateral approach

1. Place the patient supine but with the flank on the affected side elevated by placing a sandbag under the loin.

2. Make a lateral subcostal incision 1 cm below the costal margin and cut through all layers down to, but not including, the peritoneum.

3. Strip the peritoneum from under the diaphragm until you reach the abscess. Open it and drain it.

4. If you cannot find pus, carefully explore with a needle and finger through the peritoneum and be prepared to enter the peritoneal cavity.

Transperitoneal approach

1. Site the incision according to the site of the abscess derived from the preoperative ultrasound or CT scan.

2. If you are unsure of the site of the abscess or of the cause, carry out a complete exploration of the abdomen before entering the abscess cavity. This is to avoid the need to carry out an exploration after opening the abscess and risking general contamination. Explore the right and left subphrenic and sub-hepatic spaces, and enter the lesser sac through an avascular part of the hepatogastric omentum.

3. As soon as you encounter an abscess, pack off the area from the rest of the abdomen.

4. Now open the abscess, suck out the contents and drain the cavity through a separate stab wound in the abdominal wall.

REFERENCES

1. Gervais, D.A., Ho, C.H., O’Neill, M.J., et al. Recurrent abdominal abscesses: incidence, results of repeated percutaneous drainage, and underlying causes in 956 drainages. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004; 182:463–466.

2. Lam, S.C., Kwok, S.P., Leong, H.T. Laparoscopic intracavitary drainage of subphrenic abscess. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1998; 8:57–60.

Andersson, R.E. Meta-analysis of the clinical and laboratory diagnosis of appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2004; 91:28–37.

Cooper, M.J. Manifestations of appendicitis. In: Williamson R.C.N., Cooper M.J., eds. Emergency Abdominal Surgery. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1990:221–232.

Engstrom, L., Fenyo, G. Appendicectomy: assessment of stump invagination versus simple ligature: a prospective, randomised trial. Br J Surg. 1985; 72:971–972.

Gillick, J., Veayudham, M., Puri, P. Conservative management of appendix mass in children. Br J Surg. 2001; 88:1539–1542.

Jones, P.F. Suspected acute appendicitis: trends in management over 30 years. Br J Surg. 2001; 88:1570–1577.

Kirk, R.M. Basic Surgical Techniques, 5th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. [p. 161–73].

Krukowski, Z.H., Irwin, S.T., Denholm, S., et al. Preventing wound infection after appendicectomy: a review. Br J Surg. 1988; 75:1023–1033.

Rao, P.M., Rhea, J.T., Rattner, D.W., et al. Introduction of appendiceal CT: impact on negative appendicectomy and appendiceal perforation rates. Ann Surg. 1999; 229:334–349.

Silen, W. Cope’s Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.