11 Apparent Life-Threatening Event and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

Apparent Life-Threatening Event

Clinical Presentation

Infection, gastrointestinal pathology, toxic ingestion, metabolic decompensation, and trauma (both accidental and nonaccidental) are among some of the serious conditions that may initially be identified as an ALTE. Chronic conditions may also present initially as an ALTE (Box 11-1).

Box 11-1

Conditions That May Present Initially as Apparent Life-Threatening Event

RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Evaluation and Management

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

Etiology and Pathogenesis

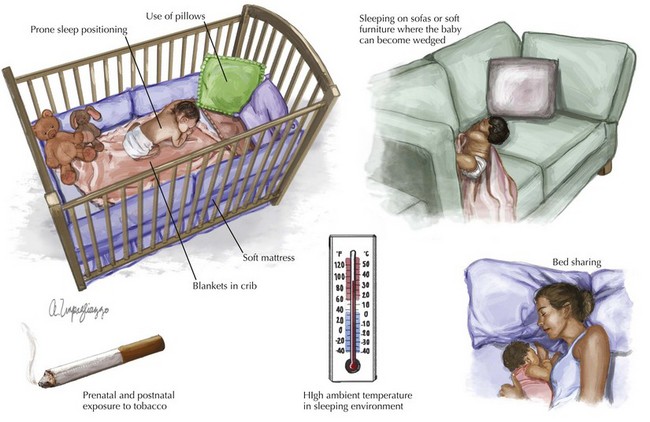

The most recent research suggests that SIDS is a polygenic, multifactorial condition inclusive of genetic, environmental, behavioral, and sociocultural factors. Well-established extrinsic risk factors for SIDS include prone sleep positioning; use of pillows, soft mattresses, or blankets in cribs; sleeping on sofas or other soft furniture in which the infant could become wedged; bed sharing; high ambient temperature in the sleeping environment; and prenatal and postnatal exposure to tobacco (Figure 11-1).

Clinical Presentation

A family that has experienced one SIDS death has a 2% to 6% risk of a second SIDS death. In the case of recurrent SIDS deaths, inherited disorders must be ruled out. Additionally, although nonaccidental trauma and homicide are rare, they are important considerations when evaluating the cause of infant death, particularly with a subsequent sudden unexpected death in a family or with a single caregiver (see Chapter 12).

Evaluation and Management

An infant coming to the ED in cardiopulmonary arrest should be managed as per the principles of Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) with a brief period of well-executed CPR. CPR is a series of interventions aimed at restoring and supporting vital functions after apparent death (see Chapter 1). This involves cardiorespiratory monitoring, careful management of airway and breathing (including definitive airway management with artificial ventilation), vigorous monitored chest compressions, intraosseous and/or intraventricular access, and two to three doses of epinephrine. During this period, the patient’s history should be reviewed with the parent, if available, and with the emergency medical services personnel, and the infant should be examined thoroughly with a primary and secondary survey. The examination should include evaluation for signs of prolonged death such as rigor mortis, corneal clouding, and dependent lividity. The infant should be transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit if resuscitative efforts achieve cardiorespiratory stability. Infants who arrive in the ED in asystolic arrest have a poor prognosis. Prolonged resuscitation efforts past 20 minutes, without return of spontaneous circulation, are usually futile in the absence of treatable problems such as hypothermia, drug overdose, or ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. The team leader should make the diagnosis of death and decide about discontinuation of resuscitative efforts based on the foregoing.

Apparent Life-Threatening Event

Brand DA, Altman RL, et al. Yield of diagnostic testing in infants who have had an apparent life-threatening event. Pediatrics. 2005;115:885.

Claudius I, Keens T. Do all infants with apparent life-threatening events need to be admitted? Pediatrics. 2007;119:679-683.

DeWolfe CC. Apparent life-threatening event: a review. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52(4):1127-1146.

Fu LY, Moon RY. Apparent life-threatening events (ALTEs) and the role of home monitors. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28:203-208.

Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U, Hof D, Peglow UP, et al. Epidemiology of apparent life threatening events. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:297-300.

Mittal MK, Shofer FS, Baren JM. Serious bacterial infections in infants who have experienced an apparent life threatening event. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(4):523-527.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy Statement: Apnea, Sudden infant death syndrome, and home monitoring. Pediatrics. 2003;111:914-917.

Collaborative Home Infant Monitoring Evaluation (CHIME). National Institute of Health. Available at http://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/supported/chime.cfm

Kinney HC, Thach BT. The sudden infant death syndrome. N Eng J Med. 2009;361(8):795-805.

Moon RY, Fu FY. Sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28:209-214.

Ramanathan R, Corwin MJ, Hunt CE, et al. Cardiorespiratory events recorded on home monitors: comparison of healthy infants with those at increased risk for SIDS. JAMA. 2001;285:2199-2207.