Chapter 5 APPARENT LIFE-THREATENING EVENT

Causes of ALTE

• Munchausen by proxy (suffocation, intentional salt poisoning, medication overdose, physical abuse, head injury)

Gastrointestinal Causes (most common, up to 50% of diagnosed cases)

Key Historical Features

Evaluation of risk factors for ALTE

Evaluation of risk factors for ALTE

Description of the event (best obtained from the most direct witness)

Description of the event (best obtained from the most direct witness)

Key Physical Findings

Height, weight, and head circumference

Height, weight, and head circumference

General impression of the child’s well-being

General impression of the child’s well-being

Dysmorphic features or obvious malformations

Dysmorphic features or obvious malformations

Neurologic examination, especially muscle tone and reflexes

Neurologic examination, especially muscle tone and reflexes

Appropriateness of developmental stage

Appropriateness of developmental stage

Signs of trauma/bruising (retinal hemorrhage, battle sign, raccoon eyes)

Signs of trauma/bruising (retinal hemorrhage, battle sign, raccoon eyes)

Suggested Work-up

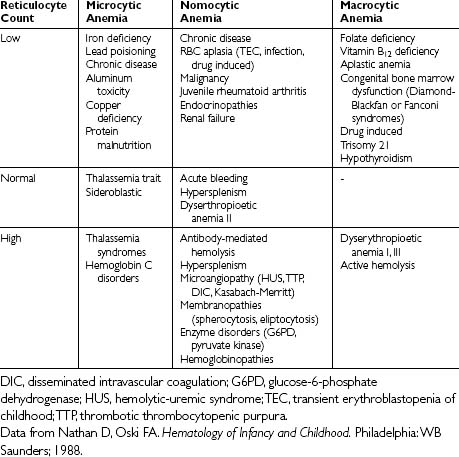

| Complete blood cell count (CBC) with differential | To evaluate for infection or anemia |

| Electrolytes, magnesium, and calcium | To evaluate for electrolyte disturbance or metabolic abnormalities |

| Serum bicarbonate | To evaluate for hypoxemia or acidosis |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine | To evaluate for dehydration or renal disease |

| Serum lactate | To evaluate for hypoxemia, toxin exposure (salicylates, ethylene glycol, methanol, ethanol), or hereditary enzyme defects (glycogen storage type 1, fatty acid oxidation defects, multiple carboxylase deficiency, methymalonicaciduria) |

| Serum glucose | To evaluate for hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia |

| Urinalysis and urine culture | To evaluate for urinary tract infection |

| Chest radiographs | To evaluate for infection or cardiomegaly |

| Electrocardiography (ECG) | To evaluate for arrhythmia or QT abnormalities |

Additional Work-up

The following tests may be indicated based on findings from the history and physical examination:

| Blood cultures | If infection/sepsis is suspected |

| Brain imaging (computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) | To evaluate for trauma, neoplasm, or congenital abnormalities |

| Nasal swab for RSV | To evaluate for RSV infection |

| Pertussis culture/serology | To evaluate for pertussis infection |

| Radioisotope milk scan or esophageal pH | To evaluate for gastroesophageal reflux |

| Nasopharyngeal aspirate | To evaluate for upper airway infections |

| Liver function studies | To evaluate for hepatic dysfunction |

| Lumbar puncture with spinal fluid analysis and cultures | If meningitis is suspected |

| Stool cultures | If infection is suspected |

| Urine toxicology screen | If metabolic disorder or accidental/intentional overdose is suspected |

| Skeletal survey | To evaluate for previous or current fractures |

| Echocardiogram | To evaluate for valvular dysfunction or structural abnormalities |

| Pneumogram | To evaluate for breathing problems |

1. Brand D.A., Altman R.L., Purtill K., Edwards K.S. Yield of diagnostic testing in infants who have had an apparent life-threatening event. Pediatrics. 2005;115:885–893.

2. Farrell P.A., Weiner G.M., Lemons J.A. SIDS, ALTE, apnea, and the use of home monitors. Pediatrics in Review. 2002;23:3–9.

3. Hall K.L., Zalman B. Evaluation and management of apparent life-threatening events in children. American Family Physician. 2005;71:2301–2308.