11 Aorto-Ostial and Branch Ostial Lesions and Unprotected Left Main Percutaneous Coronary Interventions

Techniques for Ostial PCI

Balloon Catheter Placement

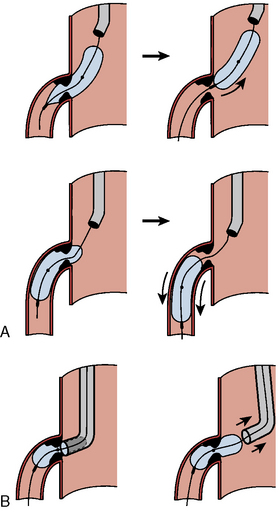

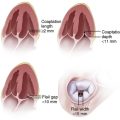

Balloon angioplasty requires seating such that, during inflation, the balloon will not be ejected from, nor compressed forward past (“watermelon seed”), the coronary ostia (Fig. 11-1). Removal of the guide catheter into the aorta immediately before balloon inflation will permit the balloon to be inflated partly in the coronary ostium and the aorta and outside the guide catheter. The lesion will be appropriately spanned by the two ends of the balloon inflating at equal pressure. Inflation in the guide may result in failure of the distal end of the balloon to inflate properly. Stenting the ostial lesion may produce strut “hangout” into the main vessel, a common complication of ostial branch stenting, especially when angiographic angles do not allow good visualization of the takeoff. An anchor wire technique may obviate this problem.

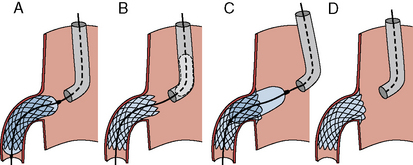

Figure 11-2 demonstrates good techniques for RCA ostial stenting. Recovering access to the main vessel after ostial stenting can be difficult depending on the angle of the ostium origin and the amount of stent. It may be helpful to leave the stent balloon catheter in place and advance the guide catheter over the balloon to minimize damage or disfiguration of the recently implanted stent.

The Back-Stop Technique

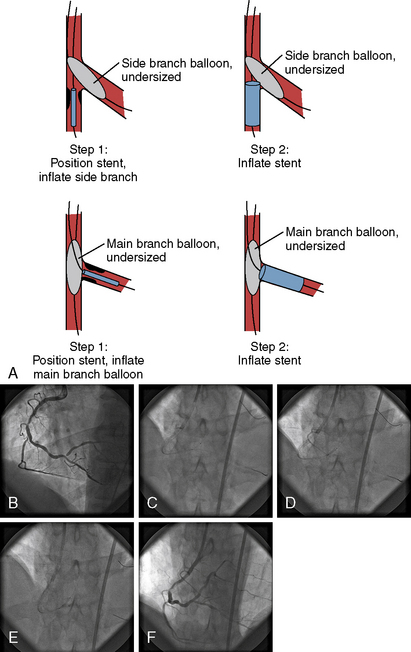

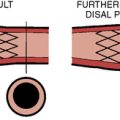

A strategy to prevent strut hangout uses a main vessel balloon inflated at low pressure (balloon:artery ratio 0.7:1), placed prior to branch stent deployment (Fig. 11-3). By pulling the ostial stent back against the inflated balloon and then deploying the stent, one prevents significant strut hangout into the main vessel.

Ostial or Very Proximal LAD Stenosis PCI

Based on the historical incidence of LM dissection and the potential for abrupt vessel closure, stent placement (with or without preceding Rotablator) has superseded routine balloon angioplasty for ostial LAD lesions. However, even in the drug-eluting stent era, ostial LAD artery stenting still has a higher restenosis rate than non-ostial locations (> 15%). Key points for ostial lesion stenting are shown in Table 11-1.

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

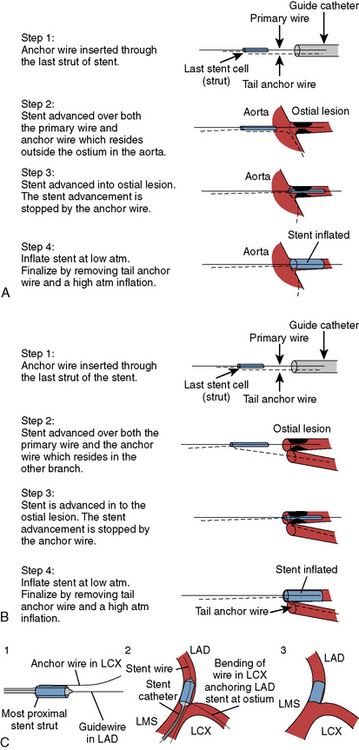

The Szabo Technique for Precise Ostial Stent Placement

In 2005, a technique to accurately place the stent and anchor it from advancing beyond the ostium of a lesion using a second angioplasty guidewire positioned in the aorta or opposing branch was reported. The technique using the most proximal end of a second guidewire passing it through the last cell of the stent inhibiting advancement and anchoring the stent position was first described in an abstract at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics conference by Szabo et al., but never brought forward into full publication. Our lab, and later others, described several cases for anchoring both the distal and proximal portions of the stent with the Szabo wire technique. The Szabo technique for aorto-ostial lesions (Fig. 11-4) and for bifurcation ostial lesions is described below:

Step 1: Begin with putting one wire into the target vessel and the anchor wire through the guide and into the aorta (or opposite branch). The very proximal end of the anchor wire is inserted through the last strut of stent. Take care on lifting the stent cell so as not to puncture the balloon.

Step 2: The stent is advanced over both the primary and anchor wires together. Remember the anchor wire is outside the ostium in the aorta (or in the opposite branch).

Step 3: The stent is advanced into the ostial lesion. The stent advancement is stopped by the anchor wire.

Step 4: Inflate the stent at low atm. Deflate the balloon. Remove the tail anchor wire and then perform a high atm balloon inflation.

1. Before proceeding with the stent anchor, one should test the passage of the stent to the target lesion. By running the stent over the main guidewire to the lesion, the forthcoming double-wired stent movement will not be impeded by tortuosity, calcification, or other complicating features. Thus, after inserting the tail of the anchor wire into the last cell of the stent, the passage of the stent over the two wires should go smoothly.

2. Careful management of the guide catheter position is needed both on stent entry and anchor wire withdrawal. Resistance on anchor wire withdrawal should be of concern, especially if any kinking or excessive bending was present.

3. Any stent balloon might be damaged by the setup of capturing the last cell with the end of the anchor wire. Careful technique is needed to thread the end of the anchor wire through the stent cell without puncturing the balloon.

4. Guidewires with polymer coating or other coatings should be avoided because of the risk of stripping the coating with distal particulate embolization. Caution is emphasized if hydrophilic guidewires are used to minimize resistance of the anchor wire withdrawal. It is also unknown if the polymer coating on the drug-eluting stent plays a role in modifying the resistance to withdrawal of the anchor wire.

Left Main PCI

Anatomic factors that have been associated with worse outcomes include:

Alexander J.H., Hafley G., Harrington R.A. Efficacy and safety of edifoligide, an E2F transcription factor decoy, for prevention of vein graft failure following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 2005;294:2446–2454.

Applegate R.J., Davis J.M., Leonard J.C. Treatment of ostial lesions using the Szabo technique: a case series. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72:823–828.

Biondi-Zoccai G.G., Lotrionte M., Moretti C., et al. A collaborative systematic review and meta-analysis on 1278 patients undergoing PCI for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2007;155:274–283.

Buszman P.E., Kiesz S.R., Bochenek A. Acute and late outcomes of unprotected left main stenting in comparison with surgical revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:538–545.

Chieffo A., Park S.J., Valgimigli M. Favorable long-term outcome after drug-eluting stent implantation in nonbifurcation lesions that involve unprotected left main artery: a multicenter registry. Circulation. 2007;116:158–162.

Gutiérrez-Chico J., Villanueva-Benito I., Villanueva- Montoto L., et al. Szabo technique versus conventional angiographic placement in bifurcations 010-001 of Medina and in aorto-ostial stenting: angiographic and procedural results. EuroIntervention. 2010;5:801–808.

Hamada Y., Kawachi K., Yamamoto T., et al. Effect of coronary artery bypass grafting on native coronary artery stenosis: comparison of internal thoracic artery and saphenous vein grafts. J Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;42:159–164.

Karthikeyan G. Why is disease progression more rapid in the proximal segments of grafted coronary arteries? Int J Cardiol. 2008;125:431–432.

Kern M.J., Ouellette D., Frianeza T. A new technique to anchor stents for exact placement in ostial stenoses: the stent tail wire or Szabo technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:901–906.

Khot U.N., Friedman D.T., Pettersson G., et al. Radial artery bypass grafts have an increased occurrence of angiographically severe stenosis and occlusion compared with left LIMA and SVGs. Circulation. 2004;109:2086–2089.

Lee M.S., Jamal F., Kedia G., et al. Comparison of bypass surgery with drug-eluting stents for diabetic patients with multivessel disease. Int J Cardiol. 2007;123:34–42.

Lo H., Kern M.J. Use of a branch wire to anchor stents for exact placement proximal to bifurcation stents: the reverse Szabo technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;67:904–907.

Lopes R.D., Hafley G.E., Allen K.B., et al. Endoscopic versus open vein-graft harvesting in coronary artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(3):235–244.

Price M.J., Cristea E., Sawhney N., et al. Serial angiographic follow-up of sirolimus-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:871–877.

Sabik J.F.III, Lytle B.W., Blackstone E.H., et al. Comparison of saphenous vein and internal thoracic artery graft patency by coronary system. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:544–551.

Serruys P.W., Morice M.C., Kappetein A.P., et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–972.

Szabo S., Abramowitz B., Vaitkus P.T. New technique for aorto-ostial stent placement [Abstr]. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:212H.

Tabata M., Grab J.D., Khalpey Z., et al. Prevalence and variability of internal mammary artery graft use in contemporary multivessel coronary artery bypass graft surgery: analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Cardiac Database. Circulation. 2009;120(11):935–940.

Teirstein P.S. Percutaneous revascularization is the preferred strategy for patients with significant left main coronary stenosis. Circulation. 2009;119:1021–1033.