4 Aortic regurgitation

Salient features

History

• Asymptomatic (but may have normal or depressed left ventricular function)

• Dyspnoea and fatigue (from left ventricular impairment and low cardiac output initially on exertion)

• Symptoms of left ventricular failure in later stages

• Angina pectoris is less common than in aortic stenosis; usually indicates coronary artery disease.

Examination

Pulse

• Collapsing pulse (large volume, rapid fall with low diastolic pressure)

• Visible carotid pulsation in neck (dancing carotids or Corrigan’s sign)

• Capillary pulsation in fingernails (Quincke’s sign)

• A booming sound heard over femorals (‘pistol-shot’ femorals or Traube’s sign)

• To and fro systolic and diastolic murmur produced by compression of femorals by stethoscope (Duroziez’s sign or murmur).

Heart

• Heart sounds are usually normal.

• Apex beat will be displaced outwards and forceful may be seen and/or felt.

• Third heart sound is heard (in early systole with bicuspid aortic valve).

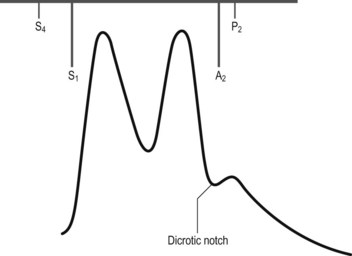

• Early diastolic, high-pitched murmur is heard at the left sternal edge with the diaphragm; if not readily apparent, it is important to sit the patient forward and auscultate with the patient’s breath held at the end of expiration (Fig. 4.1). When the ascending aorta is dilated and displaced to the right, the murmur may be heard along the right sternal border as well.

• An ejection systolic murmur may be heard at the base of the heart in severe aortic regurgitation (without aortic stenosis). This murmur may be as loud as grade 5 or 6, and underlying organic stenosis can be ruled out only by investigations.

• Ejection click suggests underlying bicuspid aortic valve.

• Mid-diastolic murmur of Austin–Flint may be heard at apex. It is typically low pitched, similar to the murmur of mitral stenosis but without preceding opening snap.

• Loud pulmonary component of second sound (suggests pulmonary hypertension).

General examination

• Head nodding in time with the heart beat (de Musset’s sign) may be present.

• Visible carotid pulsation may be obvious in the neck: dancing carotids or Corrigan’s sign.

• Blood pressure indicates wide pulse pressure.

• Look for systolic pulsations of the uvula (Muller’s sign).

• Check pupils for Argyll Robertson pupil of syphilis.

• Look for stigmata of Marfan syndrome: high-arched palate, arm span greater than height.

• Check joints for ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Questions

Mention a few causes of chronic aortic regurgitation:

• Hypertension (accentuated tambour quality of second sound)

• Idiopathic dilatation of the aortic root and annulus

• Seronegative arthritis (ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter syndrome)

How would you investigate a patient with aortic regurgitation?

• Chest radiograph is usually normal in mild aortic regurgitation; possibly valvular calcification, cardiomegaly.

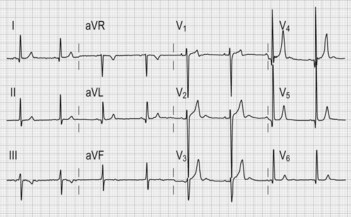

• ECG (Fig. 4.2) typically shows features of left ventricular hypertrophy and strain (increased QRS amplitude and ST/T wave changes in precordial leads) and left atrial hypertrophy (wide P wave in lead II and biphasic P in lead V1).

• Echocardiogram is indicated to confirm the diagnosis of aortic regurgitation, determine aetiology, assess valve morphology, acquire a semiquantitative estimate of severity of regurgitation, assess LV dimension, mass and systolic function, assess aortic size, in estimating the degree of pulmonary hypertension (when tricuspid regurgitation is present), and in determining whether there is rapid equilibration of aortic and LV diastolic pressure. Doppler is the best method for detecting aortic regurgitation.

• Exercise testing in severe aortic regurgitation, when sedentary or where there are equivocal symptoms is useful to assess functional capacity, symptomatic responses and haemodynamic effects of exercise.

• Radionuclide angiogram is useful in asymptomatic patients with poor-quality echocardiographic images.

• Cardiac catheterization is necessary when coronary artery disease is suspected (e.g. in patients >40 years) and when severity of aortic regurgitation is doubted; injection of contrast into aortic root gives information on degree of regurgitation and state of aortic root (presence of dilatation, dissection, root abscesses).

Advanced-level questions

What is the natural history of chronic aortic regurgitation?

What do you know about the natural history of asymptomatic aortic regurgitation?

About 4% of patients develop symptoms, left ventricular dysfunction or both every year.

What is the role of vasodilators in aortic regurgitation?

• Long-term vasodilator therapy with nifedipine reduces or delays the need for aortic valve replacement in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic regurgitation (N Engl J Med 1994;331:689). Patients in whom left ventricular dysfunction developed when treated with nifedipine respond favourably to valve replacement in terms of both survival and normalization of ejection fraction.

• Long-term treatment of patients with severe aortic regurgitation who have symptoms and/or LV dysfunction who are considered poor candidates for surgery because of other factors.

• Long-term vasodilator therapy should not be recommended for patients with left ventricular dysfunction.

• Patients with subnormal left ventricular ejection fractions should be considered candidates for aortic valve replacement rather than vasodilator therapy, since valve replacement remains the more definitive therapy to reduce volume overload.

• Vasodilator therapy is not recommended for asymptomatic patients with mild aortic regurgitation and normal LV function in the absence of systemic hypertension, as these patients have an excellent outcome with no therapy.

• The goal of vasodilator therapy is to reduce systolic BP. However, it is rarely possible to reduce systolic BP to normal because of increased LV stroke volume, and hence drug dosage should not be increased excessively in an attempt to achieve this goal. The benefit of vasodilator therapy in patients with normal BP and/or normal LV cavity size is not unknown and hence is not recommended (Circulation 1998;98:1949–84).

• A systematic review of vasodilators concluded that vasodilators inconsistently improve haemodynamic and structural parameters in asymptomatic patients with chronic aortic insufficiency. In addition, the impact of vasodilators on clinical outcomes is largely uncertain and requires further study (Am Heart J 2007;153:4542–61).

How is aortic regurgitation treated?

• symptoms of heart failure and diminished left ventricular function (an ejection fraction of <50% but >20–30%)

• concomitant angina and severe aortic regurgitation

• a reduction in exercise ejection fraction (as estimated with radionuclide ventriculography and exercise testing) of 5% or more is considered by some an indication for surgery, even in the absence of symptoms

• an end-systolic dimension of 55 mm has been suggested by several investigators to represent the limit of surgically reversible dilatation of the LV, so aortic valve replacement is performed before this is exceeded; others have challenged the validity of this limit, as postoperative reduction in chamber size remains variable.

• when aortic root dilatation reaches or exceeds 50 mm by echocardiography, aortic valve replacement and aortic root reconstruction are indicated in patients with disease of the proximal aorta and aortic regurgitation of any severity (Circulation 1998;98:1949–84).

How would you follow-up a patient with aortic regurgitation?

• Asymptomatic patients with mild aortic regurgitation, little or no LV dilatation, and normal systolic LV function may be followed on an annual basis with the advice to alert the physician if symptoms develop between appointments (Circulation 1998;98:1949–84).

• Asymptomatic patients with normal systolic function but severe aortic regurgitation and significant LV dilatation should be followed up at least every 6 months, preferably with an echocardiogram (Circulation 1998;98:1949–84).

• Asymptomatic patients with normal systolic function but severe aortic regurgitation and with more severe LV dilatation (end-diastolic dimension >70 mm or end-systolic dimension >50 mm) have a 10–20% risk of developing symptoms and hence should have serial echocardiograms every 4 months (Circulation 1998;98:1949–84).

• Patients who have had valve replacement should also be seen regularly and monitored for signs of failure of the aortic valve prosthesis (particularly in patients with biological valves) and endocarditis (Circulation 1998;98:1949–84).