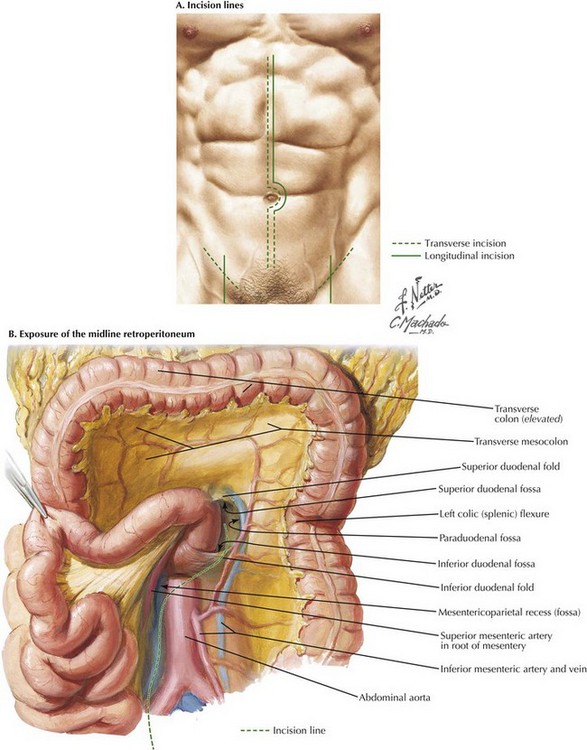

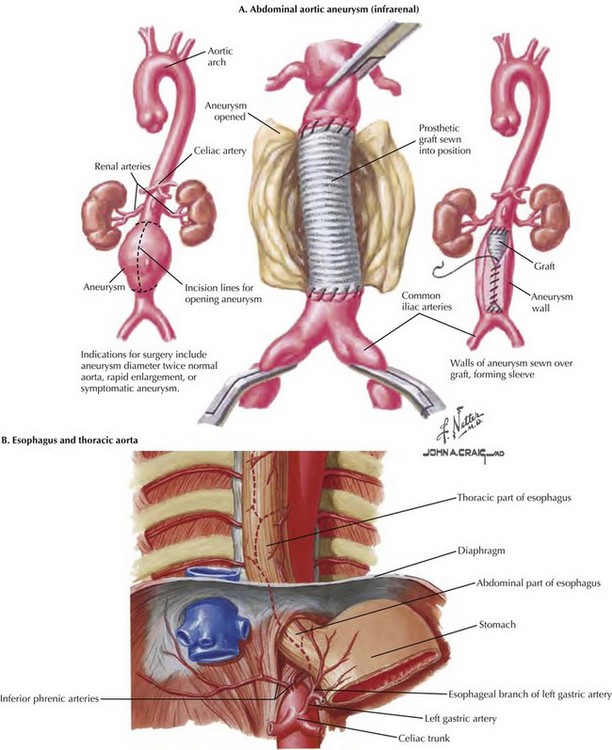

Aortic Exposure from the Midline Abdomen

Incisional Anatomy

To begin the operation, the patient is placed on the operating room table in a supine position. A midline abdominal incision is made from the xiphoid process to below the umbilicus for an appropriate distance (Fig. 33-1, A). An AF2 or AAA not involving the common iliac arteries, and for which a predetermined tube graft will be performed, is sufficiently exposed with a shorter abdominal incision. If groin incisions will be used, the groin is opened first in the patient with no previous abdominal incision, with minimal difficulty predicted in exposing the abdominal aorta.

A midline incision is made as illustrated in Figure 33-1. The small bowel is moved to the right and superiorly in the abdomen, and the sigmoid colon is gently retracted to the left. These maneuvers expose the midline retroperitoneum, and depending on the patient’s body mass index (BMI), retroperitoneal structures can be easily identified or obscured by retroperitoneal fat (Fig. 33-1, B).

Iliac Exposure

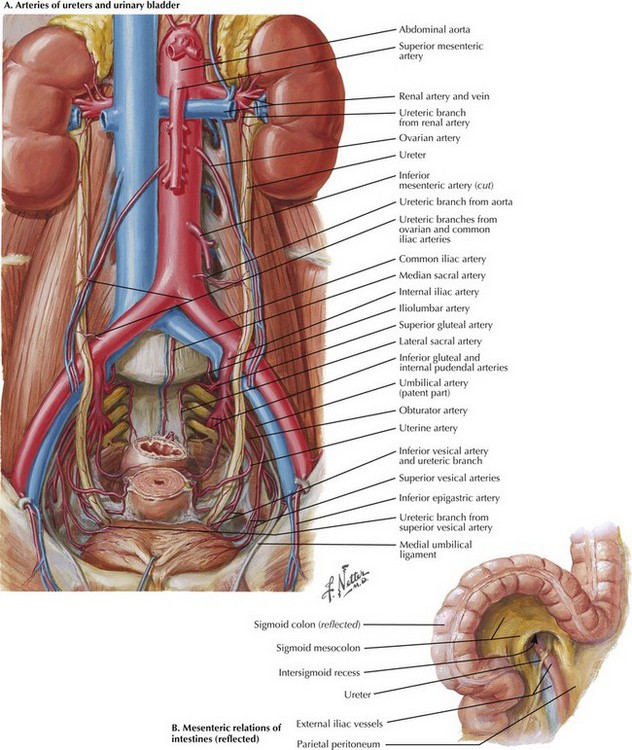

Palpation of the aortic bifurcation identifies the midline, and the author incises the pelvic retroperitoneum either in the midline or slightly to the right. This approach allows the surgeon to dissect the right common iliac bifurcation, retracting the peritoneum and its attached fat to the right. Remember that the ureter crosses the iliac vessels anteriorly and at the level of the common iliac bifurcation bilaterally (Fig. 33-2, A). Depending on the level of bypass, vessel loops can be placed around the right external and internal iliac arteries or around the distal common iliac artery, respecting the intimate relationship between the iliac arteries and veins. The most common atherosclerotic pattern demonstrates disease at the distal common iliac artery, so vessel loops around the external and internal iliac arteries are preferred. The vessels are usually soft at this location and will provide the most flexibility in constructing the anastomosis.

Lateral Approach

An alternate approach to the left iliac bifurcation is a lateral approach, reflecting the sigmoid colon’s mesentery to the right and incising the peritoneum over the left external iliac artery (Fig. 33-2, B). This approach is helpful in patients with a large, left common iliac artery aneurysm, or if the retractors used to access the left iliac bifurcation from the medial side place too much tension on the ureter or sigmoid colon mesentery. With a larger common iliac artery aneurysm, if there is known internal iliac artery occlusion, the lateral approach could allow an end-to-end anastomosis to the left external iliac artery and thus exclude the entire aneurysm.

Aortic Dissection

The main dissection of the aorta then proceeds (see Fig. 33-1, B). An incision is made along the right lateral border of the nonaneurysmal aorta and on the right side of an aneurysmal aorta. This approach is used to avoid injuring the inferior mesenteric artery or any collateral flow to the sigmoid colon. The duodenum comes into view, and the peritoneum is incised about 2 cm around the inferior edge of the duodenum, to access the plane under the duodenum and on the anterior surface of the aorta. The 2 cm of peritoneal cuff provides adequate tissue to close at the end of the aortic repair.

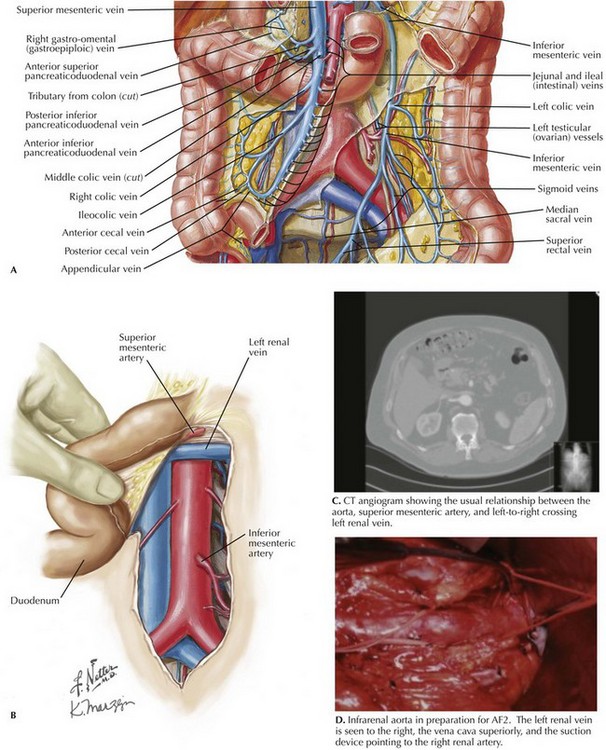

The plane on the anterior surface of the aorta is then developed, and the duodenum is retracted cephalad and slightly to the right. The inferior mesenteric vein usually can be ligated to facilitate this plan and exposure (Fig. 33-3, A). Be sure to palpate the bundle in which the inferior mesenteric vein travels; if an accompanying arch of Riolan is contributing to overall rectosigmoid blood supply, this bundle should be retracted. The goal of this dissection is to access the aorta just below the renal arteries, where a clamp should be applied for AF2 or AAA repair.

Renal Vasculature

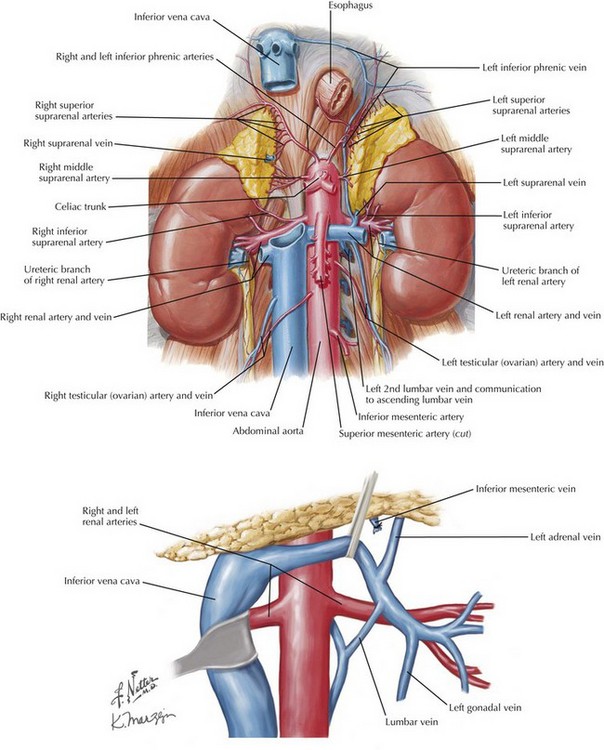

The next structure seen is the left renal vein, with its left-to-right flow and its intimate relationship with the anterior surface of the aorta (Fig. 33-3, B-D). The left renal vein can be dissected free and retracted cephalad to achieve greater exposure of the aorta and renal arteries (Fig. 33-4). The left renal vein usually marks the neck of an infrarenal AAA and lies slightly caudal to the renal arteries. The aorta can be circumferentially dissected at the level of the cross-clamp.

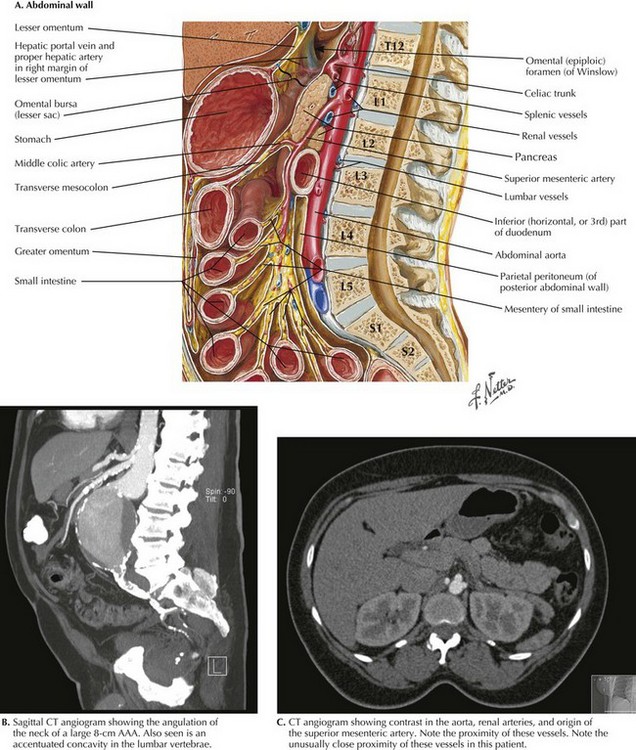

Care should be taken not to damage lumbar vessels. These vessels originate from the posterior half of the aorta between lumbar vertebrae. Therefore, instrument or finger dissection posterior to the aorta has a clear space in the concavity of the lumbar vertebrae, between actual discs (Fig. 33-5, A). With a large AAA, there is anterior deviation or angulation of the neck, allowing less dissection and still sufficient purchase for safe, complete clamping of the aorta (Fig. 33-5, B).

FIGURE 33–5 Aortic relationships with lumbar spine and visceral vessels.

AAA, Abdominal aortic aneurysm.

If the AAA is juxtarenal, or if the aorta is occluded to the renal arteries and an AF2 is being performed, suprarenal control of the aorta is necessary. To accomplish this, the surgeon decides whether the renal vein should be retracted or divided and subsequently repaired. If the left renal vein must be cut, its adrenal, gonadal, and lumbar branches should remain intact (see Fig. 33-4). The left renal vein is then secured with large bulldog clamps 2 cm apart and cut between, leaving a cuff of 1 cm on either side to repair when the procedure is completed.

Special Concerns

Dissection of the suprarenal aorta can then be done with finger and instrument dissection, but usually not circumferentially. The surgeon must always be cognizant of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and its retraction should be monitored. A space usually exists between the lateral takeoff of the renal arteries and the midline anterior origin of the SMA. The space for suprarenal clamping can vary but can be anticipated from careful inspection of the preoperative CT scan (Fig. 33-5, B and C).

Aortobifemoral Bypass

If an AF2 is indicated for aortoiliac occlusive disease, a shorter incision is usually made from the xiphoid to just below the umbilicus (see Fig. 33-1). The groin incisions are made transversely or horizontally depending on the complexity of the femoral reconstruction. The shorter abdominal incision is adequate because dissection of the aorta from its bifurcation to the renal arteries is the goal (see Fig. 33-3, D).

An end-to-side or end-to-end proximal anastomosis is done at the surgeon’s preference. If both external iliac arteries are occluded and there is flow to at least one internal iliac artery, or if a large inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) is present, an end-to-side aortic anastomosis is preferred. A shorter abdominal incision also is preferable because the femoral limbs of the AF2 are tunneled to the groin incision. These tunnels are created on top of the iliac vessels with blind finger dissection from the groins to the aorta. An infraureteral tunnel is created to prevent stenosis or pressure on the urterer after scarring around the graft occurs. The tunnels are usually marked with an umbilical tape, and the limbs are pulled through the tunnels at the appropriate time (Fig. 33-6, A).

Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Occasionally, clamping the aorta at the diaphragmatic hiatus is necessary to gain proximal control. This technique can be an especially helpful maneuver in the trauma victim with a central hematoma (Fig. 33-6, B). This dissection is greatly enhanced by placing a nasogastric tube in the stomach. Usually, this maneuver is performed under less-than-ideal conditions. The left lobe of the liver is taken down, and the anterior portion of the crus of the diaphragm is incised. With the liver retracted to the right and the stomach retracted left, blunt finger dissection on both sides of the aorta allows pressure with a sponge stick or occlusion with a straight aortic clamp.

Moore W, ed. Vascular and endovascular surgery: a comprehensive review, 7th ed, Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier, 2006.

Turnipseed, WD, Carr, SC, Tefera, G, et al. Minimal incision aortic surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:47–53.

Valentine RJ, Wind GG, eds. Anatomic exposures in vascular surgery, 2nd ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

Wahlberg, E, Olofsson, P, Goldstone, J. Emergency vascular surgery: a practical guide. Berlin: Springer; 2007.